Sunday Salawa may never have sat in a classroom or profited from any formal form of learning. She may not even know the English expression for an act she describes in Yoruba as didabe f’omobinrin, but she does know it is dangerous.

She didn’t have to be told by staff or consultants of the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) – one of the UN agencies leading advocacy against the practice. Salawa is herself a victim – a convict, so to say. Although she has committed no offence, she bears the burden of a life sentence handed down to her not by a judge but by her very own mother.

At a maternity hospital in Iwo – one of the 31 local governments in her native Osun state – Salawa went into labour in the evening of July 24, 2011, hoping to put to bed in a few hours. By dawn on July 25, she was still in labour. She would eventually put to bed under grueling circumstances.

“I had a tear when I wanted to put to bed for the first time, and that was after several hours of labour. Labour is no tea party, but mine was an especially painful process,” she recalls.

Advertisement

“When I wanted to have my second child, I had another tear. I knew that it was abnormal to have two tears in two childbirths, so it was easy for me to understand when we were told recently that circumcised women will have tears during labour.

THE PAIN OF MILLIONS

Salawa’s problem with childbirth typifies the pain of millions of women in Africa (and elsewhere across the world) who suffer a form of genital mutilation or the other. She is one of the millions of mutilated Nigerians who make up a quarter of the global population of mutilated girls/women. Whether it is clitoridectomy, excision, infibulations or their variants, 125 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in 29 countries in Africa and the Middle East – the two continents where the practice is most concentrated. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates estimates that 30 million girls are at risk of being cut within the next decade. All these women have done no wrong, but are forever burdened by the pains of mutilation, which, sadly, is an irreversible physical damage.

A 2012 report rated Nigeria as the country with the “highest absolute number” of FGM cases in the world, boasting an ignoble national prevalence rate of 41 percent among adult women.

Advertisement

NOWHERE TO HIDE

Proponents of the practice hinge it on such factors as religion, cultural prestige, and curtailing the girl’s tendency to be promiscuous. There is even a myth that uncut clitoris will grow as long as the penis! Yet, as Joy Chukwu – a nurse based in Owerri, Imo state – explains, no mutilated woman can escape childbirth complications, even if only at the first instance. Once you are circumcised, “there is nowhere to hide” during labour.

“As a nurse, once you notice that a lady is circumcised, you start planning for emergencies such as hemorrhage or suturing,” she says, chillingly.

“There MUST be a tear. Even if you carry out episiotomy, there will still be a tear from another side because the vagina won’t stretch well and dilation will be poor.

“I personally haven’t seen a lady who was circumcised yet delivered her first baby peacefully. And to give context to my statement, I have taken care of more than 200 deliveries in six years dating back to 2009. At the first time of delivery, avoiding a tear is impossible.”

Advertisement

Chukwu explains that sometimes, circumcised babies are the victims, such as with vesico-vaginal fistula, where damage to the urethra means urine flows into the vagina, resulting in a smelly baby.

From experience, she has observed that circumcised women usually suffer complications from second stage of labour, always finding it difficult to expel the baby “because of the rigidity of the vagina”. The resultant tear can extend from the centre of the vagina to the anus, causing excruciating pain that can last up to three weeks.

“The woman will experience great discomfort with sitting down, urinating and defecation, and sex will be painful for her,” she adds.

“The trauma can lead to complete loss of libido, which could be psychological problem. Like five women have confessed that to me.”

Advertisement

Well, five-less-one women made similar confessions to this journalist when the question was put to them!

SEX WITHOUT ZEST

Rosheedat Abike, a victim of FGM, cannot hide her shock when she is told privately to speak on the extent of pleasure she derives from sex. The question of “pleasure” is one the resident of Ajagba local government, also in Osun state, finds both amusing and surprising.

Advertisement

“Do I enjoy sex?” she asks rhetorically, smiling wryly. “The only thing I know about sex is that it is my husband’s right; it is not about whether I want it or not. If he wants it, I have to give it to him. It has NEVER happened that I asked my husband for it. Once he wants it, I have to want it.”

Despite admitting never experiencing pleasurable sex, it is an irony that Abike, now 35, has been in and out of the labour room four times, and currently carries her fifth pregnancy.

Advertisement

Like Abike, 35-year-old Habibat Suraju, another FGM victim, does not engage in intercourse for pleasure; only for her husband’s satisfaction.

“It is my husband who demands sex, and I satisfy him. When he says he is ready, I have to be, since he is my husband. He is the owner; and when the owner demands for his right, you have to give him.

Advertisement

“But it has never happened that I initiated sex, or even that I wanted it and I didn’t know how to initiate it. Never.”

Salimot Monsurat, 29, doesn’t expressly say she doesn’t enjoy sex. Her dilemma is that it comes with a great deal of pain because she was “circumcised as a kid when we didn’t know it was wrong”.

“I think I enjoy sex, but I experience pain around my vagina before, during and after sex, which sometimes makes me want to run away from having sex. I know it would have been different if I wasn’t circumcised.”

Far from popular belief, the benefit of pleasurable sex to the woman transcends recreation and procreation. As UNFPA’s Nkiru Igbokwe says, a woman who has had good sex “is on top of the world”.

“When a woman has had good sex, the joy is written all over her face.

“She gets to the office in the morning kicking and ready to take on any task. It is a psychological boost that mutilated women are denied – forever.”

LABOUR-TIME CIRCUMCISION

Although majority of mutilated women are subjected to the practice in their first few days or weeks of life, some still have the ill-luck of experiencing it after becoming full-grown. So says Jude Ohanele, programme director of Development Dynamics, a non-governmental organization based in Imo state, southeastern Nigeria, where FGM is also commonplace. Of all the southeastern states, it is in not-too-distant Ebonyi state, where his agency has also worked, that he has seen the gravest injustice to women.

“FGM is still done in 90 percent of the homes in Imo state,” he says.

“If not for my knowledge of this, my wife or my mother-in-law would have done it without my knowledge. It is going under the nose of so many men and they don’t even know.

“In Ikwo, Ebonyi state, it’s a major right of passage. The ladies are mutilated between the ages 13 and 16, and these girls really clamour for it. If you don’t do it, you haven’t arrived. And it does appear that is the first time the girls receive real gifts in their lives. They buy them new clothes and hold a big ceremony.

“They do it to older women, too. If you marry an Ikwo man and you fall into labour in that community and you’re uncircumcised, they will definitely yank off your clitoris during childbirth.”

SLOWLY, STEADILY, STEALTHILY… PROGRESS IS BEING MADE

Since 2010, when the World Health Organisation (WHO) and seven other UN agencies and six professional organisations issued a global strategy to stop healthcare providers from performing FGM, a measure of progress has been recorded. Although statistics of the reduction are unavailable, the testimonies are heartwarming.

For example, of all the circumcised women who agreed to tell their stories, only one circumcised one of her girls. All others had come to the conclusion that the practice is bad and their daughters should be exempted from the fate they suffered as kids.

“I have only one girl; she’s seven and I didn’t circumcise her,” says Abike. I was told at the maternity centre not to circumcise her, and we heeded the advice.”

It is the same with Salawa, who says that although she was circumcised, she didn’t circumcise her daughter because of her own experiences and the education she got at the hospital.

“Although I was circumcised, I didn’t circumcise my own daughter because we were told at the hospital not to allow the practice,” she says.

In recent years, a number of local and international agencies have been revving up the campaign against FGM. UNFPA, for example, engages individuals and groups at national, state and community levels to interact with mothers and plead with local circumcisers to shun the practice. It also trains journalists and social media activists, who in turn pass on their education to the public.

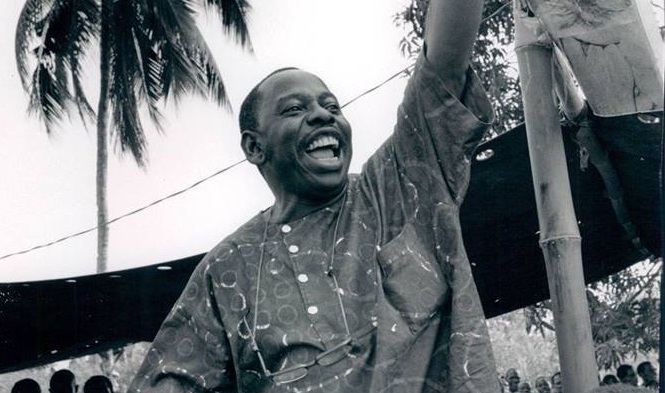

It is due to engagements like this that septuagenarian Ademola Ogunwale jettisoned his decades-long ‘career’ in circumcising girls.

“Three years ago, the government and some campaigners called us to a meeting and asked us to stop it,” says the resident of Alajue in Ede South Local Government of Osun state. “Everybody now knows that the practice has stopped in this community. More so, the government said it is bad and that it has to be stopped.”

Increased advocacy and pressure also led to the passage of the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Bill by the legislature. Four days before he left office as president, Goodluck Jonathan signed the bill (which, among others, criminalises FGM) into law. While this will not spawn an abrupt end to FGM, a legal framework for prosecuting recalcitrant circumcisers will be useful in the long term.

THIS IS ALL PROPAGANDA

For all the progress generated by intense advocacy, there is still work to be done, as evidenced by the pronouncements of Remi Ajagbo Alabelewe, a circumciser so lost in the practice that it reflects in his other name.

For Alabelewe (name literally transcribed as circumciser-cum-herbalist), who boastfully describes himself as “an author, a journalist and a presenter”, the anti-FGM campaign is nothing more than western-world propaganda.

“We are just colouring the situation; there is no issue as far as FGM is concerned,” he says in Osogbo, where he was cornered on the streets for a quick interview.

“In the olden days, there used to be tribal marks. FGM will move away without any promo or propaganda. When tribal marks were going to stop, nobody moved around telling people to stop it.”

It is unclear where exactly Alabelewe stands. In a breath, he says he has used his “widely-listened-to” radio programme to ventilate the anti-FGM message. And in another, he defends FGM proudly, obstinately – insisting that the practice is sane, and blaming health mishaps on infiltration of the circumcising “profession” by “untrained personnel”.

“We are practitioners; we were well-trained, and circumcised women had no health or childbirth issues – until infiltrators came in,” says Alabelewe who was born into a family of circumcisers, and therefore started circumcising early, in his teenage years.

So, if he finds no harm in FGM, why has been involved in promoting the message against it? In his answer, he likens the anti-FGM message to religious faith.

“It is just indoctrination; they say FGM is wrong,” he says firmly, eyes roving from one interviewee to the other.

“We have never seen Jesus Christ or Mohammed, but we go to church on Sundays and to Jumat on Fridays. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen Jesus, but I have not.”

WAR AGAINST SELF

Who would ever have thought that women – victims of the practice – are the ones mounting the stiffest resistance to the ‘Stop FGM’ campaign? But that is the exact revelation of Esther Bosede Adeniji, executive director of Osun state-based Brighter Future Initiative for Women and Children.

“Men are not actually the problem of this thing; it is the females, the elderly ones who can influence the decision of young mothers,” says Adeniji, who was circumcised herself, and underwent episiotomy during each of her five deliveries.

“The women are the ones who usually insist that uncircumcised girls will be jumping from a man to another. But if you tell a man that he will enjoy his woman more if her clitoris is not tampered it, you will easily win him over. Women are the problem.”

Adeniji’s claims tallied with the account of circumcised Oyebanji Wosilatu, whose first daughter would have been mutilation-free were it not for her mother-in-law.

“Since I’ve known female genital mutilation, it has always been meaningless to me. Okay, I understand male circumcision, but what does the female version mean? I circumcised by male children, but female? No way!” the 54-year-old says.

“When I had my first girl, I took her to my mother-in-law, and she insisted on circumcising her. I refused, but she literally forced me to take the girl to the general hospital. She said she was circumcised and that even me, I was. So, in short, my first daughter was circumcised. But, after that, I didn’t circumcise my other two daughters, because I didn’t even take them to my mother-in-law.”

CONSOLIDATING THE PROGRESS – QUICKLY

Eze Ben Nwankwo, the traditional ruler of Amala Autonomous Community in Ngor/Okpala local government area of Imo, is glad to be alive in an era where one could now ask his female subjects if they were circumcised or not. Once upon a time, asking was pointless because almost every girl was!

In his estimation, this progress will be stunted unless circumcisers are kept busy with more productive engagements.

“If you really want to remove chewing stick from somebody’s mouth, and you’re introducing something that is alien to him, you must introduce that thing quickly by giving him tooth brush and tooth paste,” he says, taking an abrupt pause before adding: “Otherwise he looks at you today, and tomorrow he returns to the chewing stick.”

Editor’s Note: This piece was produced with support from UNFPA/Action Health Incorporated (AHI)

Add a comment