Ogoni land... ruined and deserted

Eight months after she lost her daughter to oil spill, Annkio Kie (not real name) is still struggling to fight off pain and sorrow. Mary was sick for three years, after what started as mere rashes turned out to be a severe skin disease.

“We couldn’t send her to the hospital because there was no money,” Kie says, staring at the floor in her compound.

“Since the spill has destroyed everything we had, we were unable to go to the general hospital. We were getting the traditional medicine even though they never stopped referring us to the hospital.”

And so, in the morning of March 4 2018, the daughter passed on. Nothing can be as painful as the loss of a loved one to circumstances that can be controlled but which you have no power over. Between the time she died and now, hundreds of people in Goi community, Gokona local government area of Rivers state, have been buried as well, most of whom suffered from strange sicknesses suspected to be an after-effect of oil spill in the area.

Advertisement

With frequent burials now the norm, a new day is a big testimony and celebrating one’s birthday means as much as celebrating additional ten years in life.

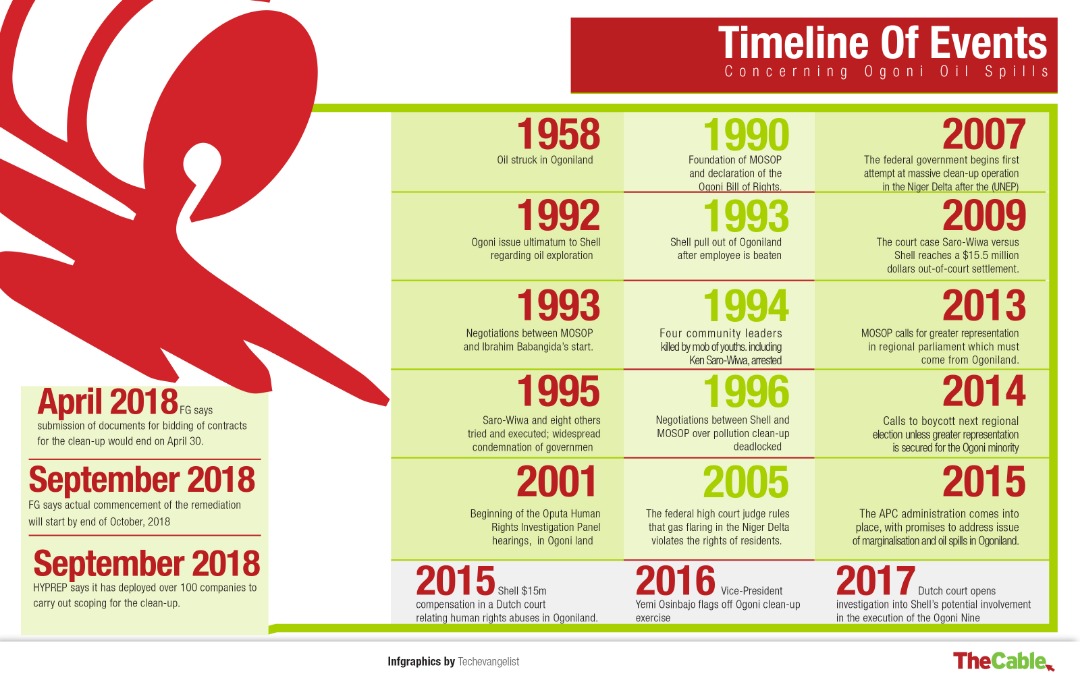

Oil spills in Nigeria dates back to the 1970s, and according to records, there were about 7,000 oil spills between 1970 and 2000. The Nigerian Oil Spill Monitor recorded some 5,296 oil spills between January 2005 and July 2014. As of 2010, Royal Dutch Shell admitted to have spilled nearly 14,000 tons (about 100,000 barrels of oil) which was majorly across the oil-rich Ogoni, made up of a total of 18 communities in four local government areas.

Amnesty International estimates total oil spill in the Ogoni to be between nine and 13 million barrels, with Shell and ENI, the Italian multinational oil giant, admitting to more than 550 oil spills in 2014 alone.

Advertisement

Goi happens to be the worst hit of the communities because it is located between two major Shell facilities; one in Bodo west and another at Bomo oil field. While the Bomo oil field is on the high land, the Bodo west is offshore. So, when there is pollution from Bodo west, the spilled crude oil is carried by the high tide into Goi creeks and farmlands. Pollution from Bomo will also see the crude oil spill downward into Goi.

“At that point, Goi is more or less like a basin,” says Eric Dooh, Lah-Bon, the traditional ruler of Goi community.

“In the end, the oil wreaks havoc and nothing is left out: the lands, the mangrove, the water bodies, the creeks. Everything is condemned.

Advertisement

Findings have shown major causes of the spills are worn out oil facilities like the pipelines as well as oil bunkering and sabotage by youth in the village.

‘ECOLOGICAL REFUGEES’

Following the damage on the environment, the affected communities in Ogoni land were asked to evacuate to give room for a clean-up exercise. But there was no plan in place for them; no shelter nor provision of adequate amenities that would make up for wherever they were leaving behind – all the government did was to put up a bill board to the effect of a relocation order.

“Since the spill, there has never been any form of compensation or remediation for Goi,” Monday Mene, a youth leader in the community, says.

Advertisement

“The only thing I can say we have received from the federal government and Shell is the sign post asking us to evacuate after declaring this place a dead zone.

Advertisement

“We are now like ecological refugees. Life has been terrible since we left; no food to eat, we have suffered from various health challenges. This (the spill) has been depopulating us day after day.”

Dooh recalls what life was like before the spills started. His father was very wealthy and had employed over 50 workers across his various business ventures including fishing and a bakery school. “But all those things are gone now,” he says with an apparent tone of regret.

Advertisement

The traditional ruler had dragged Shell to The Hague over the matter in 2003 but the case has been on since then.

‘WE BURY AT LEAST TEN EVERY WEEK’

Advertisement

Relocating sounds like moving to a safer zone but is it? At the time of the spills, the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) carried out an assessment and discovered that the water in Ogoni land had been contaminated with “high levels” of hydrocarbons. The reality of that discovery would begin to settle in when you learn that fishing and farming are the major sources of livelihood for Ogoni people.

Despite moving out of affected areas, TheCable discovered most communities in Ogoni land are still faced with the serious environmental hazards from the water, air and land and the resultant effect has been deaths and more deaths.

Doro expressed worry that no health audit was conducted among the people living in this environment.

The burials have now become a routine on mostly Saturdays and most of those still alive are not entirely lucky. Like Nuke Kambari, who hails from Mogo community, a good number of them are battling with one form of sickness or the other.

Kambari cannot exactly place what is wrong with his body system but he says “internal heat” has forced him to abandon clothes. And – you won’t believe – he has lost “so many people” to the spills.

“Some [died] when the oil spilled and they were burnt by fire. Others form sicknesses from the spill. Every weekend we are burying our loved ones from the spill,” he says, adding:

“With the oil, I am having intense heat in my body that is why you see me like this. I have to always pull off my clothe.”

‘WE WANT OUR LIVES BACK’

Since the deaths, those financially buoyant have moved out of Ogoni land to Port Harcourt, the state capital, and other safe places.

Kie is one of those still around. Despite losing her daughter, she still stays in Bodo community, a few kilometres from Goi, not because she likes the life there but because she simply can’t afford relocating.

“Children can no longer go to school, they can no longer do anything. We are living in added poverty, so we can’t go anywhere,” she says.

The mother of four then started to ask what their benefits would be from the interview; for their crops lost, for the fishes lost, for the environment and most importantly, for lives lost. The reporter assures her the story would be told to remind the government of the need to urgently intervene in their situation but she has heard that probably a thousand times. Journalists and non-governmental organisations (NGOs have thronged the area.

Despite the grievous health implications, the villagers in Gokana, left with no choice, still return to the contaminated water bodies to fetch water and to fish.

When TheCable visited General Hospital, Bodo – one of the two government hospitals in Gokana LGA, the doctors were on strike but it was gathered that villagers only come to the place in extreme circumstances.

THERE ARE SCHOOLS BUT WHO WILL ATTEND?

The education of children in the communities affected by the spill is also under threat as the schools in those areas have been abandoned. “Like, in some of those places we went, there are community schools there but you won’t see anybody there,” Mene said. “And that is because the villagers have left.”

Worse still, no alternative provision has been made to ensure the children return to school because, according to Dooh, “even if there are schools where they went, their families have lost money so nobody is talking about their education again.”

He adds: “The communities within this area are wallowing in abject poverty. There is no single government project except ones like community schools which is not in all communities and the two general hospitals you saw while coming.”

INCREASING NEWBORN MORTALITY

Children, especially the new born, are unfortunately among the worst hit in the environmental disaster in the Niger Delta. Some of the villagers who spoke to TheCable complained of how their kids have experienced unusual sicknesses both at childbirth and while growing up.

According to a study carried out by researchers at University of St. Gallen, Switzerland, oil spills are capable of causing child mortality and in cases where the children survive, their growths are usually impeded, among other hazards. The 2017 study notes that spills may increase the incidence of diarrhea and other infections as well as impaired fetal development which may lead to low birth weight, usually associated with stunting in surviving children.”

The report tagged ‘The Effect of Oil Spills on Infant Mortality: Evidence from Nigeria,’ also noted: “Oil spills that occur within this 10 kilometer radius increase the neonatal mortality rate by 38 deaths per 100,000 live births. That corresponds to an increase of 100 percent on the sample mean.

OGONI CLEAN-UP AS CAMPAIGN STRATEGY?

According to the timetable drawn by the federal government, the clean-up is supposed to start October. Ibrahim Jibril, minister of state for environment, had said about 183 companies are bidding to handle the clean-up. The villagers, however, worry this is “another campaign strategy” as similar promises in the past never saw the light of the day.

“Each time we are moving towards another political transition, governments have been using the devastation in Goi community and Ogoni at large as a way to campaign for our people to vote for them but after we vote for them, they will deceive us,” Mene said, his voice laden with sadness you can feel the weight of it.

“Now, they are promising us that from now till October, they will start the clean-up exercise. How are we sure this is not just a campaign strategy as usual?”

With the 2019 elections barely four months away, you can’t blame the villagers for doubting the genuineness of the planned remediation project. Nearly every government, since the spills occurred, have promised to take it up but look at where we are today.

GOVT SAYS IT IS DETERMINED TO START THE CLEAN-UP AS PLANNED

The government has, however, said efforts were in top gear to ensure the clean-up is successful.

After the UNEP assessment, an initial $1bn was recommended to be used over a period of five years for the clean-up, but the federal government says $177 million has so far been raised.

“As I’m talking today, that (Ogoni cleanup) account has been credited with the sum of $177m. This is what is supposed to be given by the oil majors who are there and to pay for the cleaning and restoration of those degraded lands,” Jibril had said while playing host to a delegation from the British embassy in Nigeria last month.

He had also said the balance is expected to come from the refineries and “the president has given the directives that the petroleum ministry should handle that issue.”

With each passing second, the lives of the Ogoni are being threatened the more. And like Kie said, “we want our lives back”. No doubt the time for that is now.

28 comments

The height of wickedness, may the Rewarderof mankind reward those behind this demonic act

This was so tragic. Government should do something.

What is happening in the world? So painful

Lord Save them, what a loss

It’s so painful but I pray that God will never forget them.

Lord have mercy

Jeezzz! what is really happening

OMG! Why is this happening to us in Nigeria. Its Over to God

Government should do something about this since they’re are benefiting from them.

This was so tragic. Government should do something.

This is absured and very sad to see. We are in a country where the government does not care about human life because their children are abroad enjoying

so sad to hear something like this

Buhari should intervene and do something. This is heartbreaking

And our president will never do anything

This is so sad,God please heal our land. I hope the Government do something fast

Very sad, I pray so too

This was so tragic. Government should do something.

Nawa o.. Government should please intervene in time. This suffering should stop jare

These are the kind of negative stories we keep hearing when they are the main contributors of oil which funds the country budget. Things need to change soon.

This country needs a change and it must begin with the government.

Nigeria is blessed with a lot of resources, why are we still suffering.

Another One Just Happened Again, Chai, May God Help Us In This Country.

it’s a pity that our government abandon us in ogoni land,

I just pray that God see them through.

so painful

I feel devastated reading through this post. The Government has failed us.

I pray God sees them through! Amen

The Lord is there strength, what has a beginning must surely have an end.

Sorry for them