Forced to flee their homes and settle as internally displaced persons (IDP) in camps, many young girls in Benue state keep risking their lives with unsafe abortions, while others decide to keep the pregnancy and become teenage mothers. CLAIRE MOM details the hurdles that young girls encounter in the absence of safe sexual and reproductive health services.

Life as an IDP has been hard for 18-year-old Joy Ortese. Abagena IDP camp, situated 14 kilometres outside Makurdi, Benue state capital, has been her shelter since her family fled their home following a farmer-herder communal crisis in 2020.

When Ortese discovered she was pregnant, she knew she had to “deal” with it immediately. She felt she could not raise her child in an environment where she barely had enough food to eat. Brewing a combination of herbs she had plucked from a farm nearby was the remedy she thought of. She had heard several other IDP “sisters” talk in hushed tones about how well it had worked for them. So, why not use it to get rid of the “unexpected visitor”? She used it and bled for weeks, cramped up in pain. But she knew it was only a small price to pay to escape the “burden” of being pregnant.

Some girls at the IDP camp try to practise abstinence, but their will fails them sometimes. One of them is 17-year-old Sugh Hemen who “depends on God” not to get pregnant. Hembadoon Gwaza, 16, said it was only once God let her down, but she was sure that a dose of carefulness and stronger prayers will do the trick next time.

Advertisement

Fourteen-year-old Comfort Aondohemba has been living in Mbawa IDP camp in Daudu, five kilometres away from the camp at Abagena, since she was three years. Her earliest memories in life were formed in most of the makeshift homes made with tarpaulin and plastic bags. Like every teenage girl, Aondohemba has had her fair share of hormonal changes but she is happy she knows she can go to the clinic whenever she has “problems”.

The pain in her voice was audible as she narrated how she lost two of her friends, 16-year-old Agatha Kembe and 18-year-old Dooshima Tor, to unsafe abortion.

“It was a very sad experience for me. What hurt me more was that one of them, Kembe, could have prevented it, but she chose not to take any of the drugs they gave us to prevent pregnancy,” Aondohemba said.

Advertisement

“When Kembe found out that she was pregnant, she used the barks of pawpaw tree and its seeds, ground them, and boiled them so she could drink to flush it out. Next thing, she started bleeding for weeks. She was in a lot of pain; it was so terrible. She couldn’t go to the clinic because she was too ashamed. So, we just watched her struggle till she died.”

Tor, her other friend, had opted for a more brutal option. She visited a quack doctor in a nearby primary school. She was given some drugs, while the “doctor” used a rod from a bicycle wheel spoke to terminate the pregnancy. She would later bleed to death as a result of complications from the unsafe abortion procedure.

Both parents of the deceased girls have long left the camp because of the incident. Aondohemba said they were stricken with grief and could not show their faces in public without feeling shameful.

Victor Antyev, 56, lost his daughter, his only child, to unsafe abortion. It is a memory that breaks his heart each day. Sometimes, he fears he may never recover. Antyev’s regret is that his daughter did not have a safer way to make her choice.

Advertisement

Five years of looking after the young girls have taught Esther Ortar, the women leader at Abagena IDP camp, to use a hot towel to massage their abdominal areas when they are in pain from induced miscarriages while administering painkillers. Even when she had to take care of a 19-year-old girl who had three abortions consecutively, she was discreet and non-judgmental. “It’s not easy for them not to have a child at such a young age in this environment,” she said.

A study in the Pan African Journal of Medicine estimates that 610,000 induced abortions occur annually and account for about 40% of maternal deaths in Nigeria.

Joachim Chijide, a family planning/reproductive health commodity security specialist with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), says a lack of family planning and awareness of sexual and reproductive health rights also contributes to the morbidity rates in the camps.

Advertisement

“Just because a person is in an IDP camp doesn’t mean that they do not have sexual urges or that they do not act on those urges. If they do not have access to family planning after unprotected sex, it will lead to unsafe abortions. The risk for maternal mortality and morbidity is higher for young people, which is what is happening in those IDP camps,” Chijide said.

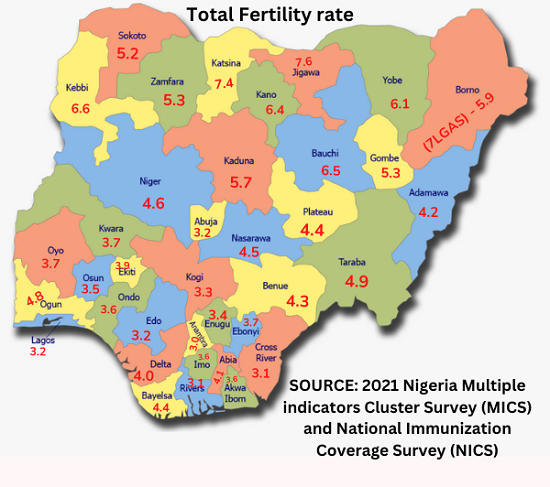

With an adolescent birth rate of 82 per 1000 women, the second highest in the north-central, Benue’s teenage IDPs contribute about 31.7% to this figure. The vulnerability of being young and tucked away from access to SRHS worsens their case.

Advertisement

At the camp, there is a conspicuous lack of functional healthcare centres. This puts the camp’s teeming population, especially pregnant and nursing mothers, at risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, a situation that is partly responsible for Nigeria’s high maternal death rate, currently put at 917 per 100,000 live births by the World Bank. This is described as one of the highest in the world.

Although there used to be doctors in Abagena camp attending to the residents, they fled the area in 2021 after a communal dispute occurred just in front of one of the camps. Now, the doctors only come around “once in a while,” according to sources, to treat malaria-stricken IDP children.

Advertisement

POOR BASIC HEALTHCARE SERVICES

In a span of seven months, 80 babies were born in 22 IDP camps scattered across Benue, according to the State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA).

Advertisement

In 2019, which shows the most recent data, there were 1,401 pregnant women and nursing mothers out of the 3,383 women of reproductive age in Abagena and Daudu I camps. However, since SEMA’s reproductive age cluster is from 18 years upwards, the figures could be higher.

Because the camp does not have a register, it is hard to keep count of the adolescent pregnancies recorded and lost, but Ortar says “it’s a lot”.

“These are young girls whose bodies are not fully developed. You see a girl less than 20 years old having at least four children in these camps. That does not help them in any way,” Apinega Aondowase, the state’s reproductive health coordinator, said.

Ortar said since the camp was established five years ago, there has never been a functional clinic. She noted that some of the young girls were able to abstain from sexual activities — a battle that was constantly lost each time she saw any of them with a protruding belly.

“Most of the girls who became pregnant have left because they were ashamed of their condition. The ones who stayed back kept giving birth or aborting the babies; but either way, it’s telling on us. If we can’t access basic healthcare, how do we get contraceptives?” she asked.

Ilya Terhile, the administrative officer at the camp, recalled how two organisations distributed contraceptives to young girls in the camp to avoid more cases of teenage pregnancies.

Unlike Abagena, Daudu camp has a functioning health facility run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF or Doctors Without Borders), an international humanitarian medical non-governmental organisation (NGO). This is where women who have sexual or reproductive issues at Abagena camp are referred to.

Services, including sexually transmitted infection (STI) treatments, family planning and care for survivors of sexual violence are rendered to the IDPs free of charge.

But with one doctor running shifts between the IDP camps in Abagena and Daudu, coupled with limited community health workers, there is little such an organisation can provide for over 4,000 women.

NIGERIA’S ABORTION LAWS VS VULNERABLE GIRLS

Sections 228, 229, and 230 of the criminal code in Nigeria’s laws are strict about the punishments for abortion — which seems to be the fastest way out of unplanned pregnancy.

“Any person who, with intent to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is or is not with child, unlawfully administers to her or causes her to take any poison or other noxious thing, or uses any force of any kind, or uses any other means whatever, is guilty of a felony and is liable to imprisonment for 14 years,” the code states.

“Any woman who, with intent to procure her own miscarriage, whether she is or is not with child, unlawfully administers to herself any poison or other noxious thing, or uses any force of any kind, or uses any other means whatever, or permits any such thing or means to be administered or used to her is guilty of a felony and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.

“Any person who unlawfully supplies to or procures for any person anything whatever, knowing that it is intended to be unlawfully used to procure the miscarriage of a woman, whether she is or is not with a child is guilty of a felony and is liable to imprisonment for three years.”

But even the tight grip of these laws has not stopped the young girls in Benue IDP camps from secretly freeing themselves from the “burden of pregnancy.”

Margaret Bolaji, an adolescent and youth sexual reproductive health expert, said the restrictive abortion laws infringe on the rights of women since it limits their choices over their bodies.

“When you look at the people who make these laws, they’re majorly men. These laws in turn do two things – it takes away the right to information and takes ownership over women’s bodies. Really, that’s what it is. When you look at that, you find out we’re still going back to the patriarchal system we’ve always been in. A woman should be able to decide if and when she wants to have kids,” Bolaji told TheCable.

“Since the law has been implemented, has that stopped abortions? Sadly, it has even increased the rate of unsafe abortions which has led to more loss of lives. We need to ask ourselves if the restriction is the solution to the problem of unsafe abortions that we have.

“Sometimes, when they (women) go to quacks for these abortion services, the quacks use that as an advantage and sexually violate them. Now that’s two problems in one.”

NO STATE FUNDING FOR FAMILY PLANNING

Following decades of advocacy for a budget for family planning services in Benue state, an allocation of N10 million was finally passed in 2021, forty-five years after the state was created. Even at that, Comfort Sor, the state family planning (FP) coordinator, said the 2022 budget of N20 million alongside that of 2021 is yet to be released.

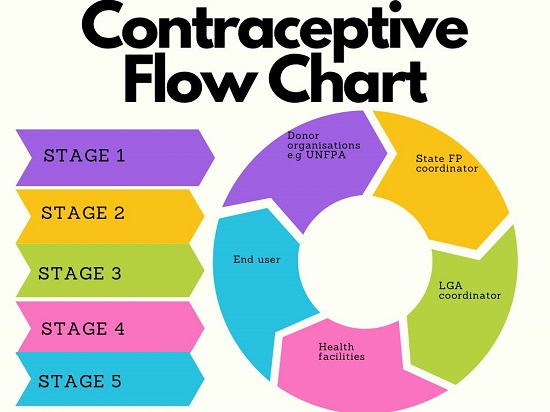

Sor said the state relies on donor organisations such as the UNFPA and MarieStopes to supply contraceptives.

The lack of access to reproductive health is worse for the female IDPs who are tucked away from easy access to health services. Then, there is no special allocation for IDPs in the state.

Due to limited funding, Sor said she, sometimes, pays for the transportation of contraceptives to the LGA family planning coordinators.

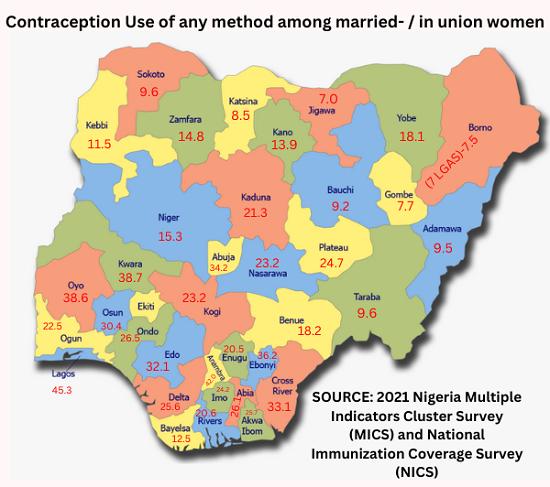

“Right now, we have over 500 health facilities in Benue. Quarterly, we receive a batch of contraceptives from donor organisations to service a population of over two million women,” the state FP coordinator said.

Sor, however, insisted that the contraceptives are enough to go around, but confidential documents seen by this reporter revealed that the intrauterine devices (IUDs) disseminated across the state were as low as 60 pieces. The most distributed items were male condoms a little over 11,000 pieces.

When asked for the reason for the low dissemination rates, Sor said it hinged on the availability of contraceptives and sometimes, a lack of awareness on the part of the women.

“Sometimes, it’s about choice and individual perception. Sometimes, the girls are not fully aware of their options,” she said.

According to Aondowase, the state reproductive health coordinator, the only IDP camps in Benue with a fraction of access to sexual and reproductive health services are the ones situated in Guma LGA, where Daudu camp is situated, and that is only because of the interventions of NGOs.

“A budget line was created and we wrote a memo to the governor for approval and release of funds to implement activities in that regard. But at this point, we’re only hoping and praying for the release of funds to carry out SRHS,” Aondowase said.

“The environment the IDPs stay in is not even helpful for them to cater for themselves; they could slip into depression. What of other adolescent girls who are yet to deliver? There’s every need for the issues of sexual and reproductive health rights of the IDP adolescent girls, specifically in North Bank, to be looked into.

“It’s been worrisome for our department because we want to look into these issues but we can’t. How can we work without money?”

Joseph Ngbea, the state commissioner of health, declined to speak on the matter when contacted.

SEMA’S PLIGHT

The State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA) is plagued with a heavy burden to cater for over two million IDPs, which is about half of the entire population of the state — a number that “grows every day, with the majority being women,” according to the agency.

In September 2021, the federal government had, in the national policy on internal displacement, shifted the responsibility of catering for IDPs to the states.

“The state government is responsible for the welfare of its indigenes while the federal government is concerned with the welfare of all Nigerian citizens,” Sadiya Farouq, minister of humanitarian affairs, said.

However, Emmanuel Shior, SEMA’s executive secretary, said he is not aware of any policy.

“The federal government, particularly with respect to the IDPs in Benue, has not done enough. In fact, there is a high level of negligence, some kind of turning a blind eye to the humanitarian situation here. You only hear about Borno and some other parts of the north-east. So, what have they even done in the first place to start shifting responsibility to the state?” he asked.

“Frankly, there is no allocation for health in our budget. We partner with the state ministry of health and other concerned organisations.”

Victoria Daaor, the executive director of Elohim Development Foundation and a gender-based violence specialist, believes that the neglect of the IDPs is creating inequalities and stunting national development in the long run.

“As long as we keep having population explosions in the camps, it’s going to keep falling further from the responsibilities of the government. The government is overwhelmed. As a psychologist, I’ll tell you that we’re grooming a set of people in these IDP camps that are full of resentment and despair. When you’re bringing up a person in a place where there seems to be no hope, you’re just building a time bomb,” she said.

“You build the country by building individuals. Nobody is talking about these IDPs going back home because insecurity is still high. The nation is going on like nothing is happening. We’re talking about elections, life is happening, but there’s a set of people who cannot go back to their homes. How can development be happening?”

For Daoor, the wealth of a community is measured by the least person there and by those indices, “no one in Benue is better than the least person in any of those camps where there is no livelihood.”

Although there are no laws directly addressing SRHR/S, policies have been created to tackle the problems that have an influence over the quality of health for women.

But Bolaji said it has been a case of talk without action. She opined that the implementation of policies must begin to take centre stage, adding that state actors have to start waking up to their responsibilities.

“At the end of the day, what is important for us as a country is that women should feel adequately empowered and knowledgeable enough to be able to access reproductive health services. It is a human right,” the UNFPA specialist said.

Editor’s note: The real names of the young girls mentioned in this story were changed to protect their identities given the sensitivity of the topic.

This report was facilitated by the Africa Centre for Development Journalism (ACDJ) as part of its inequality reporting fellowship supported by the MacArthur Foundation through the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism.

Add a comment