A woman holds her malnourished baby at the State Specialist Hospital, Nutrition Stabilization Centre, Potiskum... Photo credit: UNOCHA/Chima Onwe

Aisha was sandwiched between a sea of women, her 22-month-old baby squirming in her arms. It had been six long hours of waiting for their turn to see the officer in charge of the outpatient therapeutic programme (OTP), and she still had no idea when they would be called. The baby’s sudden cry broke her from worried thoughts; it was time to feed her. Aisha scanned the room for something to give her hungry child.

The woman sitting next to her gave a sympathetic smile, understanding the struggle all too well. She handed Aisha a bottle of water that looked almost yellow, like overly diluted tea. Aisha’s mouth watered at the sight, but she knew the children needed it more than her. She carefully fed Saadatu, who was too weak to hold the bottle herself but drank desperately as if she had not had water in days. It might have been the only nourishment Saadatu would get that day.

The 22-month-old baby was born with sickle cell disease and had developed sores in her mouth weeks ago. Before then, she had already struggled to gain weight due to limited food and clean water. The sores only made things worse for the already fragile child.

This was not Aisha’s first trip to the Primary Health Care (PHC) Centre in Tudun Wada, a ward in Potiskum LGA, Yobe state. For the past four years, during every lean season, the 25-year-old mother of five would come to the hospital to see if she could access free, ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF) to feed her malnourished children. But this year, the situation is worse.

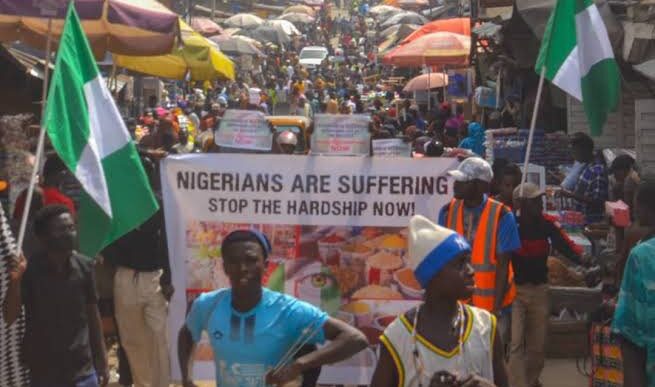

Advertisement

Yobe is experiencing its worst nutrition crisis in nearly 15 years. The fast-deteriorating situation was intensified by the severe food and economic crises caused by armed conflict, below-average rainfall, and accessibility challenges to farmlands and clean drinking water.

In past years, Aisha would rely on customers who wanted new hairdos for some N100–N200 (less than 50 cents) to feed her family. But now, her customers’ priorities have changed from adorning their heads to filling their stomachs, leaving Aisha and her children to rely solely on her husband, who makes an unstable monthly income of about N5,000 (three dollars) from selling flashlights in market squares.

“I do not know what to do. Every day, I pray to God that things should improve, but nothing seems to change. My children and I need to eat but what do we do?” Aisha asked while cooing a whimpering Saadatu.

Advertisement

“A pack of spaghetti costs about N1,500 the last time I checked, and my family and I eat at least one pack and a half. How do I pay for that? It is not easy.”

‘WE EAT GRASS TO SURVIVE’

In 2021, some 15 households (50 individuals) of internally displaced persons (IDPs), driven away from their homes in Borno and some parts of Yobe by insurgents, informally settled in Abujan Mai Mala, Damaturu, Yobe state.

The makeshift camps constructed by the IDPs now cater to 175 households (795 individuals), according to Nana Firdausi, INTERSOS camp coordination and camp management (CCCM) monitor.

Advertisement

However, the Yobe government does not formally recognise IDP settlements, leaving camps to be located on private lands, including residential plots and farms. This means IDPs have to contend with host communities for unfettered access to food and water. Often, this spikes tension, but Firdausi said violence has never been recorded.

However, it has put significant pressure on the few resources available.

“In this community, for example, there is only one water source,” Firdausi said, pointing to a borehole crowded by children with cans and buckets.

“But nearly every week, it develops a fault. Sometimes, people store water for days in unclean buckets to drink, bathe, and cook. Others that do not have what to store the water in have to walk miles to get water.”

Advertisement

Storing water is the least of Maryam Garba’s problems. The pregnant woman is more concerned about what her family of eight will eat to survive each day.

With no job or livelihood, Garba is forced to go into the bushes to find edible leaves so she and her children can eat.

Advertisement

“This leaf is not easy to find,” she said, pointing to a stem. “Sometimes, you have to walk for hours before you find it.”

“We boil it with a little salt and eat. Sometimes, we are lucky to find oil and Maggi (seasoning) to add for taste, but when we don’t, we eat it like that.”

Advertisement

Garba said sometimes the situation is so dire that she does not put on her mini stove for weeks because she cannot afford kerosene. When days like that loom, the expecting mother plucks twice as many leaves as she would need, boils them, and keeps them out to dry.

“You cannot store the boiled leaves; they will spoil. You cannot leave them like that; they will wither. So, you have to do something,” she said.

Advertisement

“That is why we boil and dry them. Since we cannot afford to boil and eat, we can chew dry ones.”

The taste of the leaves, Garba said, is a bitter assault on the senses — a sharp, astringent greenness that clings to the tongue like a stubborn weed.

The possible effect of the food’s composition on her unborn child is worrying for her, but the 37-year-old said she can only seek antenatal help if she survives. Staying alive, for Garba, means feeding on grass.

POOR SANITATION FACILITIES

Before Action Against Hunger (ACF) reconstructed the camp’s toilets, waste disposal for the IDPs meant using the open lands. Now, keeping the convenience clean is a fresh challenge, as the scramble for water means the little available is rationed for more “essential” needs.

Approaching the toilets, the air hung heavy in the tiny stall. The stench, a potent mixture of neglect and decay, seeped through partitions of zinc that were once a hopeful shade of blue and cast a dizzying spell long after leaving the scene. Impatient people, unable to accurately perch on the toilet pit, left trails of blood and other waste on the floor.

“We do not have Izal to maintain the toilet; there is no soap or detergent; there are no brooms,” Firdausi said.

Using local brooms without detergents works sometimes but the CCCM manager explained that the straw used to make the brooms is often used to create makeshift shelters.

“Sometimes, because the straw is not enough to make the shelters, when rain falls, it falls into their homes,” she said.

While a handful of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities have been constructed in some rural areas and IDP camps, the maintenance conditions of some of these infrastructures remain poor.

Hygiene awareness and sanitation levels remain generally very weak, resulting in frequent breakouts of waterborne diseases (AWD), malaria, measles, and diphtheria. This elevates the risk of disease in a weakened immune system when combined with the aggregate effects of poor sanitation and hygiene.

THE YEARLY DISEASE OUTBREAKS

According to the CCCM monitor, there has been an increased report of cases of waterborne diseases and other related illnesses in the camp compared to previous years.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said a multi-sector needs assessment conducted in May showed that 10 per cent of the displaced population lacks access to clean water and proper sanitation facilities. OCHA added that WASH was identified as the third priority in need of support for the displaced people.

“The intervention in this area is low; most times, what we get is food from partners like SEMA and WFP, but ACF is the only one helping us with WASH,” Firdausi said.

“Most of the children here are struggling with cholera and diarrhoea; every day, I get a complaint: ‘My baby is not feeling fine, she’s purging and vomiting…’ What most people do not know is that this is the season for these kinds of diseases.

“Even going to the hospital is a challenge. The distance is about two or three kilometres, and they have to walk because they do not have the money for transportation. Even the ones owned by the government, there are some medicines that you have to pay for.”

The disease is on the rise at the diphtheria isolation centre, State Specialist Hospital, Potiskum.

Isa Mohammed, officer-in-charge, said the centre received 27 confirmed cases in five days but managing the patients has been a problem.

“We don’t even have bedsheets; patients come with theirs, and those who don’t have them use the bed that the other patient used,” the nurse began before being interrupted by a colleague drawing out syringes from an open carton under Mohammed’s desk without gloves.

A worn-out mattress, stripped of its sheets, was shoved into the office corner. It served as a provisional resting place for exhausted staff, who often retreated there for brief respites from the relentless demands of treating patients without adequate protective gear.

Beside Mohammed, a water jug with deep coats of brown on the inside and a dusty exterior sat atop a faulty dispenser.

The nurse said the staff at the isolation centre rely on hand sanitising gels, which are not always available, to rid themselves of contracting the disease. This has not always worked.

According to Mohammed, limited sanitation kits have caused cross-contamination of diphtheria from patients to staff and have also increased mortality rates.

URGENT ASSISTANCE NEEDED IN YOBE

To address some of these challenges, Muhammad Gana, health commissioner, told TheCable that the ministry has set up a rapid response team, drug preparedness against AWD, and engagement with communities has begun.

Gana also said contact tracing and immediate response have begun for transmissible diseases, while intervention plans have commenced for communities in the state.

“As it is, we’re starting SMC very soon, the seasonal malaria chemoprophylaxis, and they (health officers) have mapped all those locations, and of course, they will be taking the interventions to them,” Gana added.

SMC is a community intervention that involves administering monthly doses of antimalarial drugs to children aged three to 59 months during the peak malaria transmission season, which coincides with the lean season.

However, the commissioner noted that Yobe is not exempted from the challenges that every state health ministry in the country is facing: budget constraints, manpower shortages, and limited resources.

“The government is trying its very best. We have carried out significant interventions in many of these vulnerable places, but we are also welcome to partnerships because we cannot do everything,” Gana said.

David Lubari, head of UNOCHA sub-office, Damaturu, said strategic investment and programming can play significant roles in addressing the challenges.

“Every year, and I speak on behalf of partners, the situation continues to deteriorate. It is a multifaceted problem,” Lubari said.

The UN official bemoaned the burden on the humanitarian sector to close the gaps, emphasising the need for sustainable models in times when funding is limited.

According to an OCHA report launched in May, the survival of more than 230,000 children under five hangs in the balance this lean season if they do not urgently get treatment for acute malnutrition and other nutrition interventions. The report stated that they also need access to clean water, healthcare, and hygienic living conditions to protect them from diseases such as diarrhoea which could increase the risk of death.

OCHA seeks $306.4 million to prevent further deterioration in conditions.

In the absence of urgent humanitarian action, there will be an increased risk of excess mortality, particularly among children, due to acute malnutrition, the report said.

“Any additional risks will further complicate their health conditions,” UN OCHA warned.

Add a comment