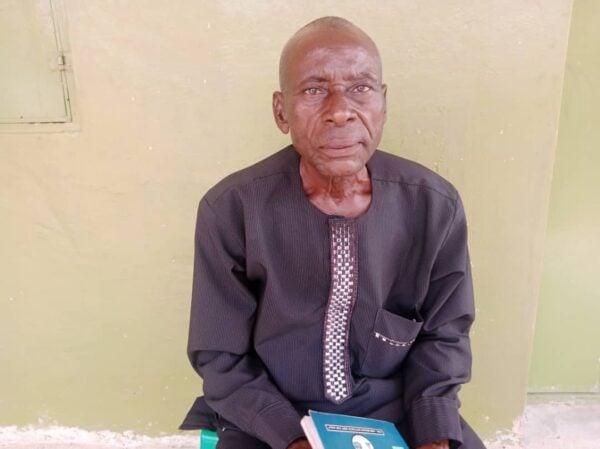

Life is nothing close to a bed of roses for Pilla Clement, a resident of Guma LGA in Benue state. The 59-year-old worries daily over how to feed his wives and 22 children. In spite of his large household, Clement had always been able to provide for his family by putting all hands to work on his cassava farm in Okekpilla village. But in 2017, everything fell apart when suspected herders attacked his village, destroyed farmlands, and burnt houses. It took a two-day walk through the bush before Clement and his family arrived at an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp.

“We’re just managing. Life has been terrible. After we were attacked, we walked and slept two days in the bush before reaching Daudu,” he said.

Clement is among hundreds of cassava farmers who have been displaced from their ancestral homes and farmlands due to the farmer-herder crisis in Benue. The situation has grounded farming activities and left a mark of sorrow, loss, and undue hardship on the lives of many.

In 2014, Isiah Uviashima lost his house and farm during an attack, and just as he was finally starting to rebuild, another set of gunmen returned to cause more havoc.

Advertisement

“The gunmen came to my place in February 2014. My home was attacked and burnt completely. At that time, everybody in my area fled, because they were killing people in my village close to Uikpam,” Uviashima narrated.

“We came back in May 2014 when we were told that the crisis had ended. Then, I was trained as a seed entrepreneur. With that knowledge, I went into cassava farming again and I had a good farm. Unfortunately, in January 2018, herders came and started attacking people, so I left the farm.”

Benue, regarded as the ‘food basket of the nation’, is the third-largest producer of cassava in Nigeria, according to Gro Intelligence, an agricultural data platform. The state contributes significantly to the 59.19 million tonnes of cassava produced yearly in Nigeria, which has made the country the largest cassava producer globally.

Advertisement

According to the Nigeria Protein Deficiency Report 2020, garri, a granular flour made from cassava, is one of the top food items consumed by the masses. In many households, it is considered the last resort.

AS THE WORLD BATTLES RISING FOOD PRICES, BENUE FARMERS LANGUISH IN IDP CAMPS

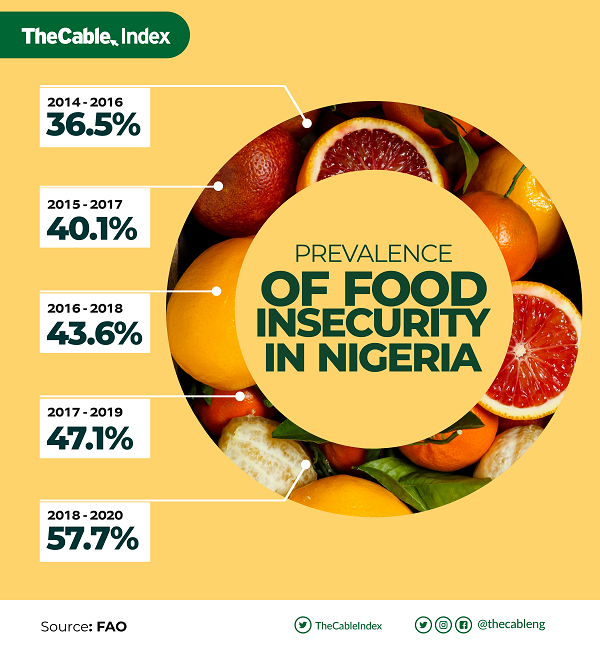

While food prices are surging globally, the situation is more pronounced in Nigeria as a result of the insecurity ravaging several parts of the country — including Benue state. The insecurity has forced many residents to abandon their farms and seek refuge in IDP camps, consequently reducing the output of cassava production and causing a shortage.

After declining in the preceding two months, global food prices jumped back up in August 2021, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Globally, farmers are trying to do more in terms of food production to cushion the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, but their counterparts in several LGAs in Benue are stuck in IDP camps.

Advertisement

Gloria Titus, a cassava farmer, now resides in Abagena IDP camp after fleeing her community in the dead of night.

“Here in the IDP camp, there is no money, no food. I stay here with my husband and two children,” she said.

Comfort Adoowasen, another female IDP who once had a cassava farm, said she settled in the camp after her village was attacked on January 1, 2018.

The Abagena camp, which provides shelter for Titus, Adoowasen, and over 8,000 farmers-turned-IDPs, was attacked in April 2021. Seven persons were killed while scores were injured. When asked why they still reside in the IDP camp despite the attack, Adoowasen said “we have nowhere to go”.

Advertisement

Solomon Azulo, the camp commandant at Abagena, spoke to TheCable about the attack and its effect on the IDPs.

“We were sleeping when herders came and started shooting people. About six persons died on the spot and the seventh person died while on the way to the hospital,” he recounted.

Advertisement

“These are typical farmers that have been displaced from their ancestral homes. They are traumatised and depressed. They have nowhere to go and this is where they now call home. Yet, we have some people coming to attack and kill them.”

Ibrahim Galma, Benue state secretary of the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association (MACBAN), says herders were not responsible for the attack as claimed.

Advertisement

“It’s an allegation that herders are responsible but it’s not true. Herders face close to 20 attacks every day in those areas which share boundaries with Nasarawa. So, those that attacked are criminals. There are issues of cultism, banditry and other forms of criminality in those areas,” he told TheCable.

Speaking on the clashes between farmers and herders in the state, Galma said herders have suffered more losses.

Advertisement

“In Benue, 90 percent of herders have become victims of attacks from farmers, and younger generations have grown in traumatic situations. From Katsina-Ala, Logo, Guande, Konshisha, even Makurdi and Guma, our losses have been unaccountable,” he said.

“Both the state and federal governments don’t care about our lives and losses, likewise the media. We are victims from A to Z. A large percentage of our animals have been killed and taken away.”

GARRI SLIPPING AWAY FROM THE MASSES’ REACH

Since time immemorial, many Nigerian households have relied on garri for survival due to its affordability. But with the price of garri recording an increase of over 100 percent in June, poor Nigerians now have to pay more for what was once relatively affordable.

Bukola Emmanuel, a garri consumer, used to buy a cup of garri for N20 in 2019, but she says it now sells for N90.

“The price of garri two years ago was cheaper. Even poor people could afford garri of one cup, which was sold for N20, but nowadays, one cup is about N90, so even garri is now difficult to take,” she said.

At Okpogba market in Okpokwu LGA of Benue state, garri sellers are grappling with the ripple effect of rising prices. Ejei Ambrose said a basin that sold for N4,000 two years ago, recently rose to N11,000, but now sells at N9,000.

The 37-year-old said the increase, which he attributed to the scarcity of cassava, has resulted in declining sales.

“There are some villages where farmers no longer farm because herdsmen have chased them away, and these are villages where they produce lots of cassava. So, with a few villages that are producing garri, the price is now high,” he said.

Production of garri is a major commercial activity in Okpokwu, one of the 23 LGAs in Benue. According to Ameh Augustine, liaison officer for the value chain development programme (VCDP) of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), Okpokwu hosts large cassava farms and supplies large amounts of garri to other states.

“Every five days, not less than 80 lorries from different states in Nigeria come to load garri from Okpokwu LGA,” he said.

Segun Adewumi, president of the Nigeria Cassava Growers Association (NCGA), said efforts must be made to improve security and ensure the safe return of residents to their farmlands.

“We had a problem last year. We couldn’t plant for some time due to COVID-19 and after that, there was no rain for three months which affected the cultivation of cassava negatively. So this, coupled with the invasion of herders, made cassava scarce this year,” he said.

“Efforts should be made to ensure that we end this insecurity because it would affect not just the price of garri, but other consumables.”

DECADE OF BLOODBATH AND BENUE ANTI-GRAZING LAW

The routes leading to many farmlands are now considered death traps. Tiamba Clement owns hectares of land in Guma LGA, but the farmland was attacked multiple times within the last four years.

“Up till today, there is no way for me to return to my home because any day I attempt to go there, I would be a goner. The herders are stationed there in Yogbo village in Guma LGA,” Tiamba said.

The challenge is not peculiar to farmlands owned by subsistence and commercial cassava farmers. It also applies to land development projects, some of which were initiated by IFAD-VCDP.

Emmanuel Igbaukum, IFAD-VCDP state coordinator in Benue, told TheCable that “I had to run for my dear life” after he encountered gunmen on a land development project meant for cassava farmers.

“It is as bad as that,” he added.

Over the years, farmers and herders in Benue state have had clashes that resulted in the loss of lives, and according to Nigeria Security Tracker, more than 1,550 deaths have been recorded in the state in the past 10 years.

One decade later, the attacks persist, with even Samuel Ortom, governor of Benue, becoming a victim during a visit to a farm on March 20, 2021.

Providing insight into the origin of the crisis, Emmanuel Igyande, kindred head of Mbabegha village, Mbabai council ward of Guma LGA, said both groups used to live peacefully until herders began to encroach on farms.

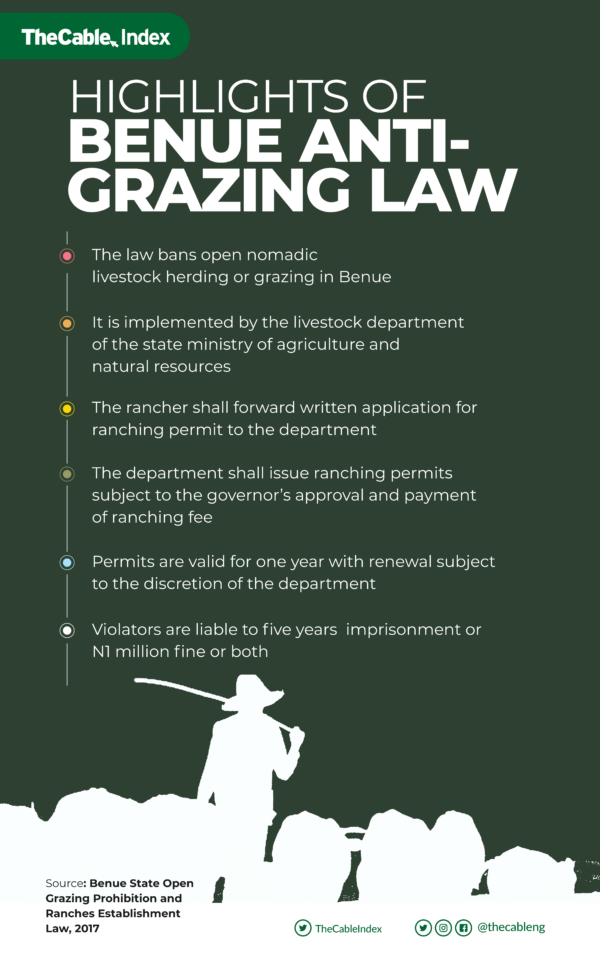

The traditional ruler said the situation became worse after the state government signed the Open Grazing Prohibition and Ranches Establishment Law in 2017, which mandated ranching for herders.

“The basis of this crisis is encroaching. Before this insecurity started around 12 years back, we have been living peacefully with herdsmen. The law was made that everyone should adopt ranching, but they (herders) have refused to accept the law. We have lost lives; we can’t visit the farms; schools and even parts of the markets are closed because of insecurity,” he said.

Terkende Chie, chairman of the Commodity Alliance Forum, a group focused on production, processing and marketing of cassava, said the insecurity has worsened because herders are insisting on open grazing as against provisions of the anti-open grazing law.

“The situation became worse when the government started arresting people for flouting the law. So now, they (herders) are saying since the law doesn’t allow them to graze, we would also not be allowed to farm. That is the problem now. Once you’re seen on your farm, you’re either shot or butchered,” Chie alleged.

The Benue state secretary of MACBAN, however, says herders are not rejecting the law but that they should have been given time to adapt before it was imposed on them.

“The process requires proper technical survey; invite experts and get capital. Before that, training capacity ought to have been done too, but herders are ignorant of this because ranching is a modern method of grazing cattle,” he said.

In 2018, the national body of MACBAN went as far as describing the anti-grazing law as a time bomb, but the state government has maintained that it will not be reversed.

IFAD-VCDP: 70% OF FARMERS SUPPORTED WITH AGRIC INPUTS AFFECTED BY CRISIS

IFAD-assisted value chain development projects have generated little results due to insecurity. The state programme coordinator said the crisis has taken a new dimension from the regular experience where herders attack only during the dry season.

The programme supports female farmers with 70 percent cost of inputs and 60 percent for male farmers.

“Most of our beneficiaries that we have supported from 2015 till date cannot return to their farms. Up till now, the farmers are still in their IDP camps. These herdsmen have taken over their ancestral homes. They have settled there and if farmers attempt to return, they are murdered in cold blood,” the coordinator said.

‘OVER 1,500 ARRESTS MADE’

Despite the seemingly bleak situation for many Benue farmers, Timothy Ijir, the commissioner for agriculture, insists that the “state government is committed to ensuring that farmers are not disturbed or their crops destroyed by herders”.

He said the anti-grazing law enacted in the state remains binding as over 1,500 arrests have been made so far.

“It is obvious that the herders are not only out to encroach on farmlands, but part of their game plan is to chase away our farmers from their ancestral homes and take possession of those lands and settle,” he said.

“But we are ensuring that doesn’t happen. About 1,500 arrests have been made for those violating the law and this has led to millions of naira in fines.”

Anene Sewuese, spokesperson for the Benue police command, said security agencies are working to end the lingering crisis.

“The police has done a lot to stop attacks in Benue state. There has been special deployment of police officers to LGAs that are vulnerable,” she said.

“There have been a series of meetings organised by the police to bring lasting solutions to this lingering problem. There have also been arrests and prosecutions.”

DIALOGUE, INCREASED SECURITY… STAKEHOLDERS RECOMMEND WAY FORWARD

To end the clashes so that residents can return to their farms, stakeholders have recommended dialogue and improved security.

The traditional ruler in Mbabegha said efforts have been made to have roundtable discussions with herders, but he alleges that they often refuse to attend the meetings.

“At times, we invite them to Nasarawa so that they won’t think we want to harm them. But even at that, they won’t come. If they had accepted our invitation, then we could have negotiated with them,” he said.

But the Benue MACBAN secretary alleged that instead of negotiations, herders have been constantly harassed and arrested.

“Government has hijacked all our efforts. We have been tagged as terrorists and criminals. We are fully in support of peace. Without peace, we all can’t survive. So, we’re ready for peace, but the government has tagged us as terrorists. We can’t move everywhere in the state, so it is difficult for us,” Galma said.

“We are doing our part conventionally by working with security agencies. MACBAN as a stakeholder is always working towards peace, because our business cannot function without it.”

Meanwhile, as each day passes, cassava farmers who have become residents of IDP camps pray that the crisis comes to an end.

For Clement, his two wives, and 22 children, hope is the only thing keeping them alive as life in the camp has resulted in more hardship.

“There is nothing above negotiation so the two parties can meet and develop a solution. I am suffering. With 22 children, things are not easy. If the insecurity issue is addressed, I will return to the farm,” he said.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment