When the first case of COVID-19 was announced in South Africa on March 5, 2020, Azubuike Muodum thought the pandemic was only going to be around for some weeks, a month at the most. A week before, Azubuike had heard about the first outbreak in Wuhan, China.

More than a year later, the pandemic is still around and has caused major disruptions around the world including affecting migrant communities and their livelihoods.

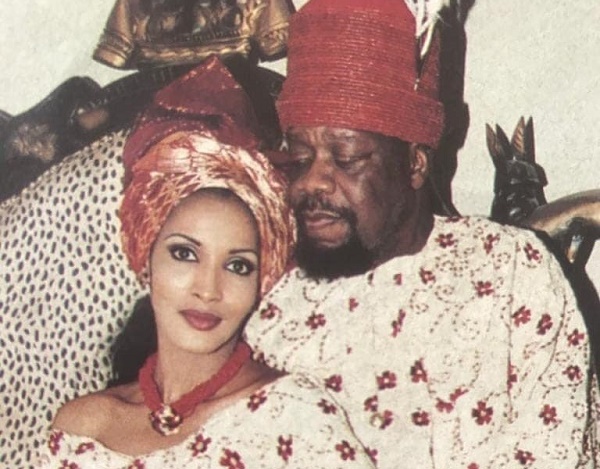

Muodum, 57, who is originally from Anambra state, Nigeria’s Southeast, moved to South Africa in 1994, and runs 1505, a medium scale popular bar and restaurant in the Johannesburg Central Business District.

He says the pandemic has greatly affected his business as patronage has dropped tremendously especially during the lockdown.

Advertisement

“This thing [COVID-19] has dealt with us a great deal even one year after it started,” he said. “Both the rich and the poor are all affected and are feeling the impact. It has not been easy but we are still on it.”

After the first case of COVID-19 was reported, the government announced a state of National Disaster in accordance with the Disaster Management Act on March 15.

Muodum, who has 10 workers from Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa at his restaurant, says paying their salaries and his monthly rental bills was difficult especially during the lockdown.

Advertisement

During the first 21-days lockdown announced last year as part of measures to curb the pandemic in the country, Muodum tells TheCable he continued paying his rental bills and the salaries of his staff.

For his monthly rent, Muodum pays R15,200 (N404,060) with an additional R6000 (N159,497) for water and electricity. His staff are paid between R4000 (N106,331) and R6000 (N159,497) per month depending on job description even when they were not coming to work during the lockdown.

“The landlord doesn’t care; all he wants is his money at the end of the month,” he says. “If you look around, you will see shops that are closed because they have lost everything or can’t pay their rent. My workers stopped working but I was still paying them because they have to eat, pay rent where they live and feed their children too. I feel it was the right thing for me to do.”

In a month, Muodum says it costs him about R45,000 (N1,196, 230) to run and manage his restaurant, but adds that it would have been more if he paid his staff their full salaries as he had to introduce a pay cut in order to survive the turbulent times.

Advertisement

Despite the impact of the pandemic on his business, Muodum says he helps vulnerable street children from poor neighbourhoods during the lockdown by preparing meals and distributing to them. Three times a week, he cooks for about 30 children.

“I leave my house and come here alone to secretly open the shop and cook for street children from poor communities who have been affected by the pandemic,” said Muodum who has been running his business in the area for the past 16 years. “I was feeling for them because they were affected and don’t have anything to eat. I have been here for many years and see them every day. They are like my people.”

‘COVID took my brother away from me’

Stanley Unaegbu’s brother, Uche Okorie, died of COVID-19 last year at Johannesburg Hospital. Unaegbu says his death took away many things from his and exacerbated the challenges associated with the pandemic that they face.

“COVID really affected us but we are surviving by the grace of God,” he says. “We had to make plans to take him home for funeral. We have not recovered from the disruptions ever since.”

Advertisement

Unaegbu, who moved to South Africa in 2000 from his hometown in Abia state, runs a small clothing business around the CBD. Before the pandemic, he says he made around R2000 (N53,165) a day but now struggles to make sales of R500 (N13,291) and R1000 (N26,582).

“There is no money and business is slow,” he says from under an umbrella where his stall is located. “We ask God to take this away from us because if this continues, we don’t know what to do again.”

Advertisement

Muodum and Unaegbu are certainly not isolated. Thousands of Nigerian migrants living in the country say the pandemic has affected their livelihoods.

The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) said some of the 272 million international migrants worldwide are more vulnerable than others because of personal, social, situational, and structural factors. According to the IOM, their vulnerabilities may be exacerbated in crisis situations, as it is the case with the pandemic.

Advertisement

South Africa is currently the epicenter of the pandemic on the continent with more than one million identified cases as at April 17, according to the Department of Health. Of this number, 53,711 people have also reportedly died from the virus.

Olaniyi Abodedele, the head of the Nigerian community in South Africa, said the community has raised more than R500,000 (N13,291,455) to help support about 500 Nigerians affected by the pandemic.

Advertisement

“His death really affected me because we were very close here,” Unaegbu said, adding that he has close family and relatives at home who depend on him for survival.

Where he lives with his South African wife and a child, Unaegbu says he pays R4000 (N106,331) per month but has not been able to keep up with payments and currently owes some months.

“I reached an agreement with apartment management to pay by installment during lockdown,” he says. “I was owing seven months but have been able to pay up for some months. I struggled with providing living expenses during the lockdown.”

The IOM says that “movement restrictions imposed at national and local levels also limited the continuation of livelihood activities, leading to a drop in global remittances further affecting remittances-dependent households in countries of origin and eroding coping capabilities,” adding that the situation “is particularly dire, given that their [migrants] employment often supports families left behind and contributes to poverty reduction, access to basic services and education worldwide”.

Anuli Ezeabata said the period of the lockdown was terrible for her family as migrants living in South Africa as they found it difficult to feed.

Ezeabata who sells beauty products in the city, moved to South Africa as an asylum seeker in 2008 from Enugu, a city in Nigeria’s Southeast region.

“We have families and children to provide for so you can imagine what that would be when you don’t make sales or make enough to pay for living expenses,” she tells TheCable. “It is tough but we are managing to cope. It is still affecting us even up till now and we have not come out of it because business is slow.”

At her shop, Ezeabata employs five staff, three South Africans and two Zimbabweans and pays each R700 (N18,608) per week. In addition, she pays more than R100,000 (N2,658,291) for rent every month and says she is still paying for past months she owed.

“During lockdown, I was still paying them [staff] because they have to eat and pay rent and bills. I had to find a way to do business and pay them,” she said. “They used to call me to tell me they don’t’ have anything to eat so I can watch them starve.”

The IOM says that it is working with governments and partners to ensure that migrants and mobile populations, including stranded migrants, returnees and displaced persons, are included in efforts to mitigate and combat the impact of the pandemic.

“Although they face the same health threats from COVID-19 as the host populations, they may face vulnerabilities due to the circumstances of their journey and living and working conditions. Loss of jobs and income, residence permits and resources have all impacted mobile populations, resulting in hundreds of thousands of stranded migrants globally,” the organisation said in a statement posted on its website.

Xenophobia – another pandemic

While migrants are struggling to survive amid the disruptions caused by COVID-19, another pandemic – xenophobia — resurfaced.

South Africa has a long history of xenophobic attacks spurred by anti-foreigner sentients migrants from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Sudan, Lesotho and Mozambique have been at the receiving end of violence as a result of xenophobic uprising in the country.

Locals say migrants from these countries come to their country to commit crimes such as robbery, drugs, human trafficking, run prostitution rings and taking away their jobs.

In 2008, the most bloody violent xenophobic attacks targeted at foreigners happened in South Africa. More than 60 migrants were killed, hundreds injured while their businesses and properties were either looted or destroyed by the mob-wielding crowd.

In the middle of the pandemic in September last year, thousands of South Africans marched across major streets and cities, calling for the expulsion of foreigners from Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Lesotho.

Anonymous and troll social media handles and accounts especially on Twitter with the hashtag #PutSouthAfricaFirst trended for weeks and aimed at sparking with anti-foreigner agenda through violence and protests.

Protestors with placards, marched to Nigerian and Zimbabwean embassies to pass their anti-migrant messages to the high commissioners.

There are more recent incidents. Last month, xenophobic attacks targeting foreigners and their businesses happened in Durban, a city in the eastern KwaZulu Natal province. Shops were razed and properties looted.

The South African Institute of Race Relations says attacks on migrants and their livelihoods highlight the consequences of governance and economic failure.

“It happens every now and then,” Muodum tells TheCable. “Whenever it starts happening, we close our shops and hide for safety.”

Muodum, however, it has never affected him directly especially when they start destroying shops and businesses.

“I live well with them and always friendly with everyone where I live and do my business,” he says. “I use my mind to associate with them and always protect myself by being lenient and help the way I can. I also don’t fight with anyone, so I don’t have enemies here so I don’t think they would attack me.”

You don’t come here and fight with the owners of the land, he adds.

South Africa’s last census, conducted in 2011, said there were 2.2 million foreigners living in the country. This number is likely to double ever since the last census was conducted.

The government has developed a National Action Plan aimed at fighting xenophobia, racial discrimination and related intolerance in the wake of violent xenophobic attacks and diplomatic tensions.

“The government is trying its best but local people don’t understand what they are doing and the impact it would have,” Muodum says. “They don’t want to hear anything because they think we are the cause of their problems but they are the cause of their own problem. If even you employ a South African now to work for you, if you pay him/her the first salary, he would leave to go and spend the money; he won’t come the next month.”

But politicians have sometimes been blamed for helping in sparking xenophobic fears in the country with anti-migrant statements especially during elections to win votes.

During President Cyril Ramamphosa’s State of the Nation address on 11 February, he said his administration was clamping down on illegal immigration and cross-border crime.

Police brutality on the rise

Amid the pandemic, cases of police brutality soared. South Africa has a notorious legacy of police brutality. More than 11 people were killed by the police while enforcing the lockdown rules with over 230, 000 people arrested for violating restriction measures put in place by the government.

Migrants from the Nigerian community say they have been extorted, harassed and intimidated by the police especially during the lockdown.

Emeka Dike, a Nigerian migrant, tells TheCable the police stopped him in November last year to demand for papers at Highpoint, Hillbrow, a popular neighbourhood for migrants in the country.

When he couldn’t provide them, because they had expired and he was unable to renew them, he was taken to Hillbrow police station, where he had to post R1,000 (N26,582) bail before being released.

Dike has been living in South Africa since moving here at the end of 2014. To sustain himself and pay the bills, he performs odd jobs around the city.

“I was beaten because at first I did not want to go with them [the police],” he said. “They forced me and dragged me into their waiting van. They said I am here illegally since my papers were not complete but I told them I was [in the process of] renewing them at the home affairs office.”

Because his papers had expired, Dike said he did not lay charges as he feared he might be arrested again and deported.

Like Dike, Nnamdi Okeke, a Nigerian said he was stopped by police in Yeoville, another migrant community in the city while at the mall to buy groceries. His papers were found to be invalid, so they asked for a bribe to avoid being arrested.

“I gave them R200 (N5,316) so they can allow me to go,” he said. “Sometimes it is R100 (N2,658) or higher, depending on those involved. But you need to be ready to pay something when they see you are here illegally, unless you want to be taken to the station.”

Okeke also didn’t open a case, fearing it might complicate his bid to get his residency permit.

Gareth Newham of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) said many undocumented migrants are in South Africa for economic opportunities, and it is often difficult to get documentation.

“The borders are porous, so that’s why we have a large number of people here,” he said. “These groups are more at risk of police brutality and corruption than people less vulnerable. So, if you are in the country without documents and you come across police officers, you can’t necessarily expect them to help you if you need help or to treat you fairly and accord you your rights.”

Newham says many of the police’s stop and search activities were targeted at undocumented migrants, to extract bribes.

“In other words, stopping people and asking them for papers and if you don’t have your papers, they will ask for money to let you go,” he said.

Research done by the Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP) at the University of Witwatersrand on immigration policing in Gauteng corroborates Newham’s position. The study found growing mistrust between the police and African foreigners, who are presumed to be immigration offenders, rather than potential sources of intelligence.

Newham says police brutality is a serious and endemic problem in the country and that there are certain segments of police officers who think that the only way to get foreigners to leave South Africa is to treat them harshly.

“It happens regularly across the country where police officers exceed the bounds of the law in terms of using force, not as the last resort or where necessary but using it too quickly to punish people that they think they don’t want to be around,” he said. “And that is what often happens to undocumented migrants who come in contact with the police. Beating people up, spraying them with pepper spray because they don’t think, for example, that the courts will take action.”

When immigrants are brutalised, they are reluctant to seek justice. Newham says it is unlikely that undocumented migrants will seek justice because they risk arrest and deportation.

“Most undocumented migrants will not use the police,” he said. “But even if you have the right papers, going to the police to report crime is unlikely for most people.”

While cases of brutality against migrant communities exist, a lack of accountability in the police system has made it difficult for officers to be sanctioned, disciplined or held accountable in most cases. Newham agrees it is one of the problems facing policing in South Africa.

“It’s not that there is no accountability because there are police officers who have been subjected to disciplinary actions when complaints are filed but not enough given the size and scale of the problem. So, it is very unlikely that an officer who is brutal or corrupt will be held accountable,” he said.

“For most officers who have been involved in the unlawful use of force or corruption, they don’t feel threatened by the accountability mechanisms or internal police processes. So, you have a situation where you have weak accountability mechanisms and weak management in terms of setting clear norms and standards and organizational culture that upholds human rights regardless whether you are living in the country legally or not.”

Muodum says he has never experienced police brutality since he has been living in the country for the past 27 years but acknowledges it happens every day.

But Ezeabata’s case is different. She tells TheCable that they were harassed by the police during the lockdown as they go out to get essential supplies.

“They will ask if you are a migrant and demand to see your papers even when you go to buy essential supplies during the lockdown,” she says. “If you are not lucky and your papers are not complete, they will harass and extort you because they know everywhere is closed and there was nowhere you could renew papers.”

Ezeabata adds that as an asylum seeker living in country, she has faced discrimination in getting permits and complete documentation at the Home Affairs.

“They will tell you to stay one side because you would be deported back to your country,” she said. “In 2017 when I went to get my papers, they said they would deport us to Nigeria because our papers were not complete. They just want you to go back home, but I was pregnant then and that was what saved me.”

When the national lockdown was announced, the South African government introduced the Social Relief of Distress Grant which provides R350 (N9,304) each month to asylum seekers and special permit holders with valid documents.

But for Ezeabata, this was not possible as she is yet to get her complete papers due to discrimination by officials at the Home Affairs.

Muodum tells TheCable he wants to retire, hand over his business to someone else and return to Nigeria where his wife and six children currently live.

“The problem in Nigeria such as insecurity and bad governance is what is keeping us from coming back home,” he says. “My prayer is for Nigeria to be good so we can go home because it is the problem that brought us here.”

Since the roll out of the Johnson & Johnson vaccines against the pandemic started in February this year, 292,623 people have so far been vaccinated. Muodum and other Nigerian migrants in the country who spoke with TheCable say they have not been vaccinated.

However, Health Minister Zweli Mkhize last week announced that the rollout of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine would be suspended amid blood clot fears reported in the United States.

“I am not happy that I’m in a foreign land,” he says, his gaze fixed on two customers walking inside his shop.

Add a comment