Butchers at “work” at a Lagos abattoir

Around 5:30 pm on a Tuesday evening in April at Itire market, one of the popular markets along Mile 2, Lagos state, 34-year-old Joyce Bassey was packing up for the day. She lifted up her head from the tray of seasoning cubes she had been packing up, sensing a possible last-minute sale as I approached her. That was when I saw her COVID-19-compliant black nose mask, placed properly on her face and the straps tucked behind her ears.

Joyce raised her voice to address me. “Customer, no go check am, no be COVID-19 make me wear this face mask, the odour is too much for me. You sef dey perceive am too na,” Joyce said in Pidgin English; meaning “I am using this face mask to avoid the odour, not for COVID-19 protocol, the stench is too much for me as you can also perceive the odour.”

Joyce is referring to the heavy stench of waste deposits from the Itire slaughter slab channel that assaults the senses of any visitor to the market.

Joyce is a petty food ingredient seller in the market which hosts the Itire Abattoir— one of the 16 approved semi-mechanised abattoirs in Lagos.

Advertisement

During Dataphyte’s visits, most of the business owners in the market and residents within the vicinity were wearing face masks as a way of reducing the contaminated air that lingers, and the stomach-turning stench that makes it difficult to breathe. But then, the masks are barely effective against the encompassing stench.

Why? The wastes generated from the abattoir are poorly managed and are being deposited within the market.

Workers at the slaughterhouse said although they sell some of their waste products to farmers and others in need of them, the leftovers are oftentimes deposited into an open canal behind the slaughterhouse.

Advertisement

As the waste decomposes, it leaves behind the token of rancid odour from the dump site and poorly channelled sewage from the slaughterhouse.

Right next to the slaughterhouse were several makeshift shops whose inhabitants were traders selling food items. Joyce was one of the traders at this spot. She has been inhaling the stench for the seven years that she has been a trader at the Itire market.

Like Joyce, many other petty traders interviewed agreed that they were significantly affected by the odour which was a result of the unsustainable environmental practices at the Itire slaughterhouse.

While many residents and traders expressed their displeasure with the offensive odour from the abattoirs’ slab, they were largely ignorant of the health and environmental implications of poorly managed wastes from slaughterhouses.

Advertisement

DIRTY ENVIRONMENT OR NOT, LIFE GOES ON AS USUAL

Joyce said she has a bit of understanding of what danger the abattoir poses to her health and those around her but she is scared to speak up about the unceasing stench taking over the air and the unclean activities due to the fear of intimidation; her survival depends on how well she can turn a blind eye and wear a nose mask.

“Not that I can’t speak up to the heads of the abattoir, but if I speak about the smell from the drainage, they will surely send me away,” Joyce said quietly so other sellers would not hear.

She explained that aside from the stench disturbing the air in the market environment, mosquitoes are as commonplace and plentiful as the sellers and buyers in Itire market, a development that often leads to malaria.

Advertisement

As of 2021, malaria led to the death of over 200,000 people in Nigeria.

Four visits on four different days to the abattoir in early April showed that Itire falls short of basic hygiene standards, which according to Tunji Bello, the commissioner for water resources, include stipulations such as “….the slab must be made of impervious material with proper drainage to collect wastewater for appropriate treatment”.

Advertisement

Dung was seen on the platform where the animals were being slaughtered and from the butcher to the buyers and other vendors in and around the butchery, no one was wearing protective boots.

Aside from the unkept drainage where Joyce and many others station their shops, the dump site situated just beside the Itire abattoir is a danger that can lead to a disease outbreak, compounding woes for the Itire community.

Advertisement

‘LEFT WITH NO CHOICE’

Samuel, a teenager manning his mother’s mini supermarket in Egbeda Idimu, a Lagos suburb, shared how the poor air quality affects his family. As he pulled out the bottled water from the generator-powered fridge and handed it over in exchange for the N100 bill, Samuel said “his nose is used to the stench coming from the abattoir.”

Advertisement

Although the abattoir operates for 14 hours, opens by 6:00 am with the slaughtering of rams and cows and closes around 8:00 p.m; for Samuel and his family, the stench doesn’t have a closing period.

According to Samuel, the stench is even worse at night and sometimes, during the afternoon. For his family, they would turn on their power generating set, close all windows and turn on the fans to blow the odour away.

“We really don’t have a choice; we are used to it over the years. My mum would ask us to close the window when the thick bad smell starts to disturb us. Then, there is mostly no electricity, and we would turn on the generator and our fans,” Samuel narrated, clearly unaware of the dangers of poor ventilation that results from shuttered windows.

LIKE ITIRE, LIKE AYOBO

Itire is not the only place affected by abattoir activities, Ayobo, another suburb in the state also shares a similar fate.

Nicknamed “playboy”, the giant-looking man in his early 40s was introduced as the head of the butchers in the abattoir located at the end of Ayobo, a border community between Lagos and Ogun states.

Playboy was quick to boast of his achievement as a butcher with over 15 years of experience in the bag, unaware of the negative impact of his exploits on his neighbours.

As he narrated his background, the scene behind him was like a play-within-a-play.

An open wide-spaced room with barefoot men holding different kinds of knives, trading jokes back and forth as their bare feet created paths on the floor which was wet with animal waste, water and dung cut from the stomach of a cow.

At Ayobo, the runoff from the abattoir is not directed to any canal. It is left to run freely into streets and open gutters. The hum of flies was as loud as that of the humans in the marketplace, perching and taking off from the pile of dung onto people’s faces and even worse, the food items laid out for sale.

For those living close to the abattoir, theirs is a story of anguish; aware that their environment is unsafe yet unable to complain because of fear, perhaps of Playboy and his cronies, but also for the sake of family members whose livelihoods depend on the abattoir, at the detriment of their health.

For fear of being attacked, one of the house owners anonymously shared his frustration. “You see here, see those houses (pointing at nearby houses) they have complained. The government officials have been here many times to warn them. You won’t smell anything now, come here early in the morning or late at night. We can’t open our windows. If only I can take away my house, sincerely, I will,” he said.

“I have been living here for many years. We can’t vent our anger too much on them because our neighbours are there among them, even our relatives. But still, the odour at times can be so frustrating.”

The activities of the facilities raise questions about the regulation of abattoirs in Lagos state.

Dataphyte findings revealed there is no public slaughterhouse on the list of approved abattoirs situated in Ayobo, indicating that the Ayobo slaughterhouse is illegal or unregistered.

TOO CLOSE TO HOME, TOO CLOSE TO COMFORT

According to The Food and Agriculture Manual for the slaughter of small ruminants in developing countries, abattoirs should be built far away from residential areas on the outskirts of town.

The reason is “…. to prevent possible inconvenience to dwelling-places either by way of pollution from slaughter wastes or by way of nuisance from noise, stench or the presence of scavenging animals such as vultures, stray dogs, etc. Conversely, remote location secures the premises from contact and likely contamination from residential units close by”.

It is safe to say that these abattoirs do not follow these recommendations, which include ventilation, because stagnant air can encourage the growth of spoilage organisms and natural lighting to discourage unhygienic practices.

One other recommendation worthy of note is that “the siting of slaughter premises near waterlogged areas must be avoided. Evidently, such sites can raise sanitation problems such as the breeding of mosquitoes and the stagnation of waste. Location near watercourses or inland bodies of water such as rivers, lakes and lagoons is also unadvisable”.

Lagos state missed this memo completely in the siting of both official and unofficial abattoirs.

MORE PUTRID ODOURS, LAGOS ABATTOIRS CONTRIBUTE TO TOXIC BIOGAS EMISSION

Globally, some seven million deaths each year are linked to the effects of air pollution, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO), making it the biggest environmental killer.

Pollution kills more people than car accidents, diabetes or dementia. The effects are particularly pronounced for children, who can experience stunted lungs and lifelong cognitive impacts.

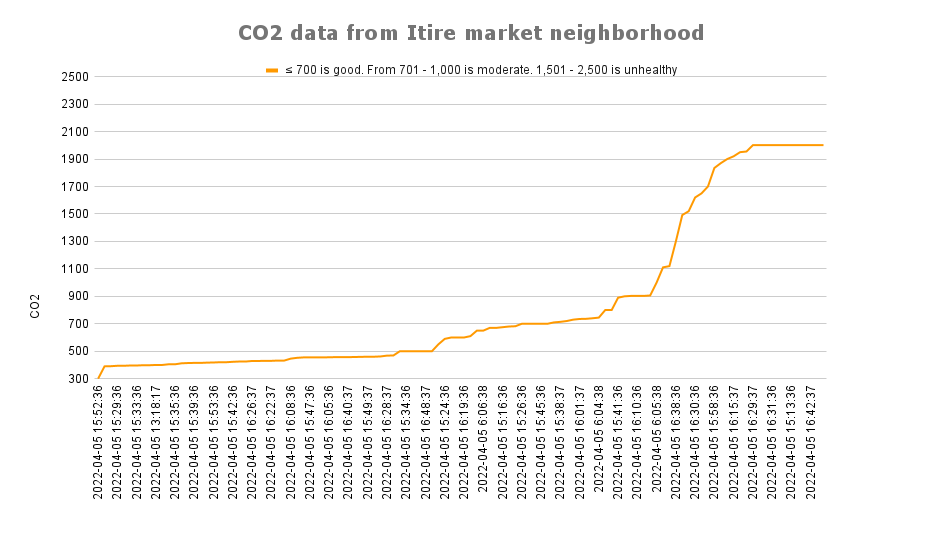

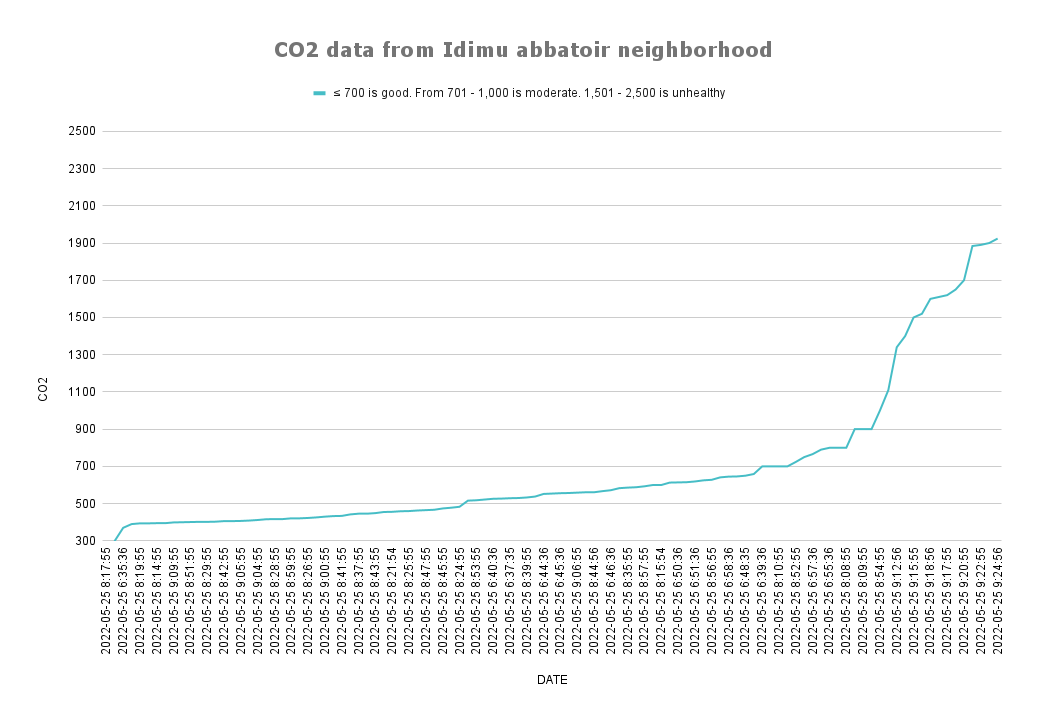

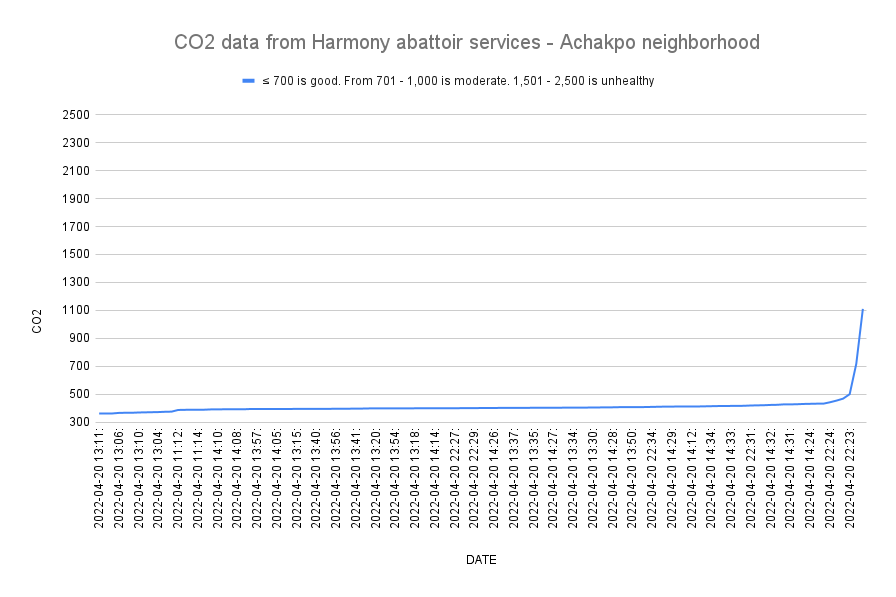

For more than four days in April, using a Temtop M2000 outdoor air monitor device, Dataphyte monitored the air quality at these abattoirs. Checking the volume of Carbon dioxide(CO2), Formaldehyde (HCHO), fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and particulate matter (PM10) around selected approved and unofficial abattoirs in Lagos, Nigeria’s economic hub.

From Itire to Agege, Achakpo to Ayobo, to Egbeda-Idimu among other nameless illegal roadside abattoirs scattered around Lagos, all these locations failed the air quality test. Residents have been breathing in unsafe air due to the contaminated high volume of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the air in these areas.

For instance, the air quality detected around the Itire market, one of the 16 approved semi-mechanised abattoirs by the Lagos government, is captured at about 2001 parts per million (ppm).

According to the generally accepted CO2 concentration, anything less than or equal to 700ppm is good, and 701ppm – 1,000ppm is moderate. 1,501ppm – 2,500ppm is unhealthy.

EGBEDA-IDIMU ABATTOIR DOES NOT FARE BETTER

This situation is the same in the Egbeda-Idimu abattoir neighbourhood where the highest and lowest CO2 level was 100ppm – 1924ppm.

According to a research paper, such a high level of CO2 in the air is unhealthy and can cause fatigue, loss of focus and concentration, and an uncomfortable stuffy feeling in the air.

Because carbon dioxide is an asphyxiant, it mostly affects the brain. At moderate CO2 levels, around 1000 ppm, there are observable effects on human thinking.

The central abattoir in Oko-Oba Agege, where over 30% of the 8,000 cattle and ruminants valued at N1.6bn said to be consumed in Lagos on a daily basis are slaughtered, fared a little better, charting at 1,654ppm.

The case is similar in Harmony abattoir services — Achakpo, Ajegunle, where 1,111ppm was the highest CO2 level charted in the area.

CO2 Levels in Four Abattoirs in Lagos

| Location | CO2 Levels | Range (Low, Moderate, High) |

| Itire | 2,001ppm | High |

| Achakpo | 1,111ppm | Moderate |

| Egbeda-Idimu | 1,924ppm | High |

| Oko-Oba Agege | 1,654ppm | High |

According to the Air Visual network project, a project of air pollution mitigation firm IQAir, the air quality of Lagos state is not good for reading and the residents are ranked as the highest population likely to be exposed to hazardous air.

POISONOUS CO2 AND CLIMATE CHANGE EFFECT

Air pollution is not caused by one single substance — many types of molecules and particles combine to create unhealthy air, and generate new pollution through chemical reactions. According to WHO, outdoor air pollution is a major environmental health problem affecting everyone in low, middle, and high-income countries.

According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), a tonne of animal waste produces over 100 cubic metres of biogas and has a concentration of 65 per cent methane (CH4) and 35 per cent carbon dioxide (CO2), both of which are among the five notorious greenhouse gases contributing to global warming.

The UNFCCC said methane has a potency of about 21 times more than carbon dioxide in terms of trapping atmospheric heat, translating to about 1500 cm3 of greenhouse gases emitted from dumpsites in every 15000 kg of waste per day.

These kinds of available data on greenhouse gas emissions portend trouble for states like Lagos but also other states in Nigeria where there are poor waste management systems. There is hardly any state in the country where mounds of waste cannot be found on street corners and marketplaces.

It also provides a lens through which Nigeria’s agenda 2060, promised at COP26, should be interrogated. Is Agenda 2060 possible without clear policy, strategy and investment in waste management systems across the country?

EXPERTS WEIGH IN

Iyaomolere Mayokun, an environmental officer and founder, Plogging Nigeria Club, said the authorities of the abattoirs must ensure sustainability in the management and handling of the emerging waste products.

Mayokun said the usual mode of “handling abattoir wastes are detrimental to the environment and are even sources of emissions that contribute to climate change.”

“For example, blood and other wastewater released during the whole slaughtering and preparation process find their way to water bodies, polluting them, affecting the aquatic life and in other cases leading to eutrophication where there’s too much nutrient in the water leading to massive algae bloom on water surfaces, which in turn leads to oxygen depletion and also affects the biotic and abiotic processes in the water,” Mayokun said.

“The animal dung and other organic wastes discarded from abattoirs upon decomposition, release carbon dioxide and methane, major culprits for global warming and climate change. In some local abattoirs where they still roast meat, that process also releases a lot of toxic fumes. Some even still use tyres, which is very dangerous for human health.”

“Some of the organic wastes rather than being discharged can be collected, treated and used as part of animal feeds. The wastewater can also be under treatment before it is finally released into the environment.”

Best Ordinoha, a public health expert and professor of medicine at the University of Port Harcourt, said the improper waste management in Lagos abattoirs may result in deadly diseases to the host community.

Ordinoha said the stench oozing out of the environment and the decomposing animals that emit sulphur dioxide, nitrous oxide and other gases can contain allergens that can trigger an asthmatic attack.

He added that the gases can be intoxicating, resulting in drowsiness and disorientation

“When abattoirs are located close to the market — another place where people congregate — they can constitute serious public health problems. These public health problems can be derived either from the animals being slaughtered or the sanitary condition of the abattoirs,” the professor said.

“From the animals, sick animals are sometimes slaughtered, especially because we don’t have enough inspectors to identify these animals and stop them from being slaughtered. So, animals with diseases such as anthrax and sometimes tuberculosis can be found in these slaughter slabs and these diseases can be transmitted to human beings.

“If the abattoir is not fully cleaned, it means certain diseases can come out of it. Certain diseases are carried by several microorganisms, especially because when the faecal matter and the blood mix together they become what is called a culture media, a media that promotes the growth of microorganisms.

“So, if this media is produced by the abattoirs, it will result in a significant increase in the number of these microorganisms. We are talking about microorganisms like salmonella ( the typhoid causative), cholera and E.coli, they can all be transmitted through these means and these are very serious diseases.”

The public health expert also said that the people in the market area and the host community staying close can be susceptible to plague and Lassa fever.

“The other one has to do with rats and other vectors. These vectors thrive in unsanitary conditions. So, you expect an increase in the rat population in these areas and their presence can lead to the transmission of diseases transmitted by rats. The common ones in Nigeria include Lassa and plagues,” he said.

NO RESPONSE FROM LAGOS STATE

For more than four weeks, phone calls and text messages sent to Abisola Olusanya, Lagos commissioner for agriculture, were not picked up or returned.

But available documentation showed that the ministry demolished over 80 abattoirs in 2020 and shut down two others in April 2021 in furtherance of the sanitisation and reform of the red meat value chain in the state. The commissioner had also in 2019 threatened to shut down Oko-Oba Agege abattoir over poor management.

Folashade Kadiri, the Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA) spokesperson, also promised to get back to Dataphyte with a response, but she is yet to do so at the time of publication.

This report was first published by Dataphyte, and produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center