Many see shea butter as a pale solid fat with an unbearable stench, but women in Kodo – a village in Bosso LGA of Niger – occupy themselves with its processing every day. They produce cosmetics, cooking oil and medicinal mixtures with shea nuts. For them, it is not just a business they do to get by and put food on the table, but a profitable venture worthy of being passed down to their female children. TheCable’s MARYAM ABDULLAHI reports how several Niger women are empowering themselves and others through shea butter.

Every morning, women from different households converge at the shea butter processing company located at the entrance of the village to begin the business that pays their bills.

Shea butter is the fat extracted from the nut of the African shea tree. It melts at body temperature and is used as cooking oil, for medicinal purposes and to manufacture a variety of cosmetics such as skin moisturiser creams, emulsion-based lipstick, hair creams and conditioners.

The demand for shea butter continues to increase globally by manufacturing companies, who use it as an ingredient for their products.

Advertisement

Sarauniya Aliyu, 57, has been processing shea for over 20 years, relying on locally-made wooden tools to extract the oil from the shea nuts.

The rigorous toiling and swirling made the processing labour-intensive but it was produced in small quantities. At the time, the shea oil produced was only for consumption purposes.

“We processed only what will last for a while. We used it as cooking oil to prepare soup and other meals,” she said.

Advertisement

When people started trooping into Kodo to tap into the business opportunity that shea presented, the women were initially daunted — but they later began to explore the fecundity of the fruits. Surrounded by forests rich in lush shea trees, they soon discovered that proper utilisation of the natural fat could earn them multiple sources of income.

At this point where epiphany intertwined with ambition, Sarauniya said the women decided to assemble themselves and establish a small association.

“Before we started the shea butter business properly, we didn’t know it could serve as a means of livelihood until people from different places started visiting our village. We were shocked and worried,” she recounted.

“We thought the people, especially the government officials, had come to banish us from our village. Some of us thought they wanted to ban us from producing shea butter.”

Advertisement

Sarauniya said the women started to go to the bush in large numbers to fetch the shea seeds, a trend which persisted for years until nomadic herders, who had settled in the forest, took interest in it.

“Before the Fulani herders colonised the forest, the shea nuts were at our disposal,” she said. “Recently, people are beginning to know the importance of the shea tree and that is why it has become difficult to see the seeds everywhere as we used to in the past. Now, we buy most of our shea nuts from the Fulanis.”

Sarauniya said virtually all the female children in the village are involved in the business, regardless of age.

“We didn’t have to teach our female children the shea butter processing business, they watched us and they are now all good at it,” she added.

Advertisement

How shea butter is produced

After the women pick the shea from the trees, they crack the shell with their hands to remove the nuts.

The nuts are then washed by the extractors, after which they are left under the sun to remove the moisture. This is followed by the pounding of the nuts into small pieces. The small pieces are then roasted on the fire until they turn into a dark chocolate paste which is mixed with water to properly soften it.

Advertisement

The women then rinse the paste with clean water severally to separate it from dirt.

They proceed to the boiling area where they separate the fat portion from the oil. The fat portion will rise to the top of the pot, leaving the oil at the bottom. At this stage, the shea oil is almost ready for use but the women usually leave the oil to settle while they pour the fat out. After this stage, the shea butter is ready for use.

Advertisement

14-year-old produces soaps, creams, cosmetics

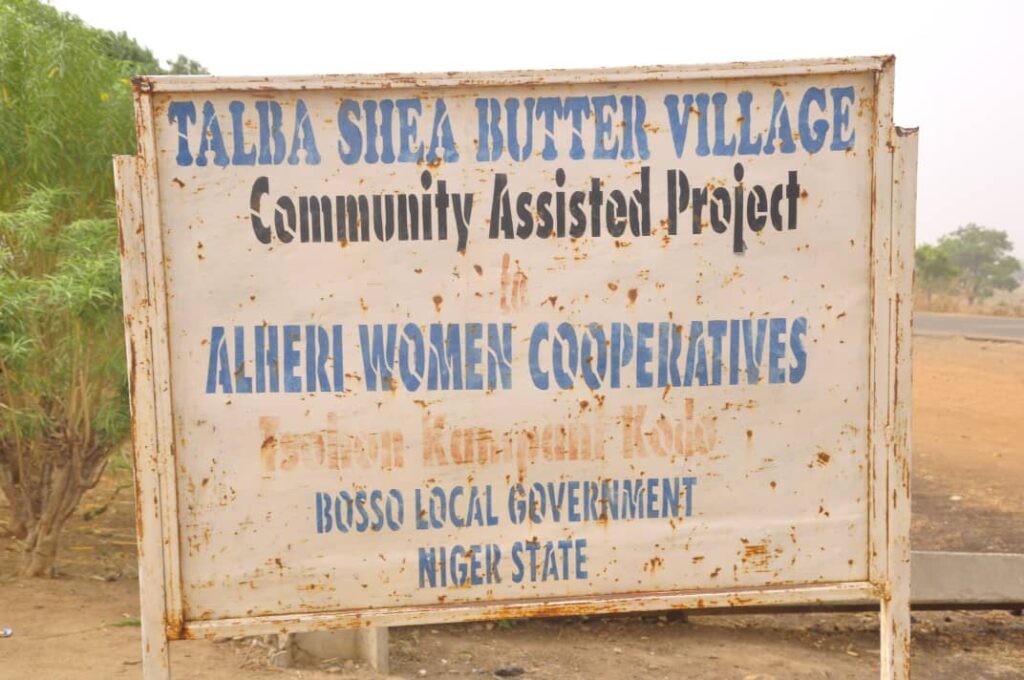

In 2011, Babangida Aliyu, former governor of Niger state, facilitated the establishment of a shea butter processing company named ‘Talba Shea Butter Village’ for the women in Kodo. With some machines and multiple processing sections made available, the women were able to produce with improved ease — raising and turning hot shea oil from one huge pot to another.

Khairat Mohammed has been working with her mother at the shea butter company for over seven years now. She stopped schooling after concluding her primary education some six years ago.

Advertisement

While understudying the older women, the 14-year-old-girl was able to learn the production of soaps, body creams and other cosmetics using shea butter.

“It was our mothers (the elderly women) that taught us how to produce cosmetics from shea butter. They went to Minna, the Niger state capital to learn the skills some six months ago. When they returned, they bought the necessary materials and we watched them while they practised the skills,” she said.

Khairat said she earns N12,000 from selling 20 litres of processed shea butter — and she reinvests the profit into the business.

‘Big business’ for Ladi Shambo

Despite being conversant with shea butter production, Ladi Shambo’s production capacity was limited to butter extraction for soaps until the visit of the Japanese to Niger state in 2008.

Some years back, Ladi could never be caught using her hands to touch the locally-made shea butter because of its smell — until the Japanese showed her a way around it.

She said people initially frowned at shea butter because of its odour, making the hard work associated with its processing less rewarding.

“In those days, people don’t value shea butter, they don’t use it because of its smell,” she said.

The 70-year-old woman recounted how as a nine-year-old, she would escort her father to his job at the Nigeria Railway Corporation (NRC) but he never allowed her to touch the shea seeds lodged by passengers at the weighing area of the train station.

“I shed tears the first encounter I had with the Japanese when they showed us the numerous values of the shea seeds,” she recounted.

“Five Japanese came to Niger with a bag of cosmetics, I watched them and asked many questions on cosmetics making. After I mastered the production process, I said to myself, this is a big business for me and my children.”

Before Ladi established the shea butter company which she named ‘Dijmeds’, she was into spice making. But after learning the tricks of the trade from the Japanese, she started making bathing soaps and other black soaps for laundry purposes. She packaged her soaps and sold them for N100 each.

“When I started the shea butter business, I received information that the federal ministry of trade and investment was calling on entrepreneurs across the country producing shea butter,” she said.

“I travelled to Abuja and displayed my products. All the people who saw my products were shocked at what shea seeds could do.”

The journey to profitability

Ladi started promoting her products by taking them to exhibitions across the country. She refused to get discouraged when the stench of her products irritated participants. Rather than recoil, she came up with other ways to improve the appeal of her products — one of which was the creation of a banner where over 50 uses of shea butter were listed and placed at the venues of exhibitions she attended.

She also realised that the offensive stench was partly a result of the kind of water used in processing the shea products. According to her, cleaner water can help to reduce the smell.

“When people come to my stand to buy my products, I take them to the banner and explain virtually all the uses to them. I didn’t relent in my efforts and I was opportune to be picked by the Nigerian Export Promotion Council (NEPC) that took me to Dubai to market my products,” she said.

A business idea and capital are like two sides of a coin. Naturally, like most entrepreneurs, Ladi had problems with finance which limited her production capacity in the early days.

“I had challenges with finance as I was only making soaps until a lady at the Bank of Industry (BOI) came across my product. She contacted me and asked me to meet her in Lagos,” she said.

“I travelled to Lagos and she prepared a loan of N8 million for me and that was what uplifted me. That was what improved my business because, without finance, you can’t do anything.”

Through her consistency and relentlessness, in 2020, Ladi won the federal government’s MSME award in the wellness, beauty and cosmetics category, earning N1 million in prize money.

Motivated by the recognition and accompanying financial intervention, Ladi realised she could help more women to get to her level, hence, she started going to villages to create awareness.

The ‘engine boy’ who grinds shea nuts

In Busugi, a village in Bosso LGA, nearly all the women are in the shea butter business. They spend three hours everyday processing. Even though the women are involved in other petty trades, their major source of income is shea butter production.

Hashimu Hassan is originally from Zaria in Kaduna state. He relocated to Niger with his boss who was into rearing and selling animals in Kaduna state. When Hassan arrived at Busugi four years ago, he observed the stress women went through to crush the shea nuts by travelling to towns where machines were available.

He recognised an opportunity to make money and alleviate the plight of the women, so he bought two blending machines for N150,000 and N170,000.

The 26-year-old now grinds a small bowl of shea seeds for N1,000 while a large bowl goes for N2,000. According to him, he grinds more than 10-15 bowls a day.

“This is the engine I use to grind shea butter. I usually collect 1,000 for small bowls and the biggest bowl is 2,000,” said Hashimu who has never had any form of education.

“If the machine is well serviced, I grind more than 10 large bowls of shea nuts a day.”

Rotational sharing formula

To ease the rigours associated with shea processing, the women join forces. While some of the women busy themselves with washing the nuts, some handle the crushing while others work on spreading them under the sun to dry.

According to Sarauniya, they jointly contribute to purchasing two trucks of shea seeds weekly after which they work collectively on the processing. The proceeds of each production cycle are given to a particular household. This is done on a rotational basis until all the households involved in the shea butter business have products to sell.

Three large pots of processed butter can fit into three 20-litres paint buckets, according to Sarauniya. In one day of production, the Kodo women produce at least 15 buckets and each costs N25, 000.

In terms of costs, Sarauniya said they spend 30,000 on firewood that lasts for over six months, while they buy a truck of shea nuts from the Fulanis at N100,000.

Most of the women in every household involved are said to earn at least N50,000 from shea butter every month.

Shea butter outlook in Nigeria

According to the UN Development Programme (UNDP), Nigeria is among the top shea nuts producing countries in Africa. The UN agency estimates that an average of three million African women work directly or indirectly with shea butter.

The Nigeria Incentive-Based Risk Sharing System for Agriculture (NIRSAL) puts the shea butter market value in Nigeria at $320 million. The country currently produces 425,000 metric tonnes of shea butter, which are largely found in states like Niger, Kwara, Kebbi and Oyo.

In 2018, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported that Nigeria earned N101.97 million from the export of only shea oil in the first quarter of the year. In 2021, Nigeria exported shea nuts worth N6.14 billion.

The Nigerian Export Promotion Council, in 2019, listed shea butter among the 22 non-oil sector products that can create 500,000 export-oriented jobs in Nigeria.

As Nigeria desperately seeks to eradicate poverty, create employment and achieve economic growth, empowerment opportunities should be targeted at shea butter-producing women such as Sarauniya and Ladi — who are drivers of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) — to enable them to continuously contribute to the sustainable development of their communities, and the country.

Add a comment