At the mention of his younger years, Morgan Agidi’s face lit up; his lips spread wide with a smile and his eyes shone. His youth was fun, the 87-year-old recalled. The 6-kilometer trek to school with friends in Abari community, Patani LGA, Delta state, was always something to look forward to. They would play football afterward on the community field close to the river and help their parents cultivate the land.

But this excitement became short-lived as Agidi began to talk about how his community has changed so much over the years. The jetty, the fields, his primary school, and his father’s house are now underwater.

Abari, Agidi’s community, has one of the tributaries of the River Niger flowing through it. The river, which serves as the main source of water for the community members, has also become a source of pain for them. Due to the annual flooding of its banks, this river has submerged homes, schools, markets, and other infrastructure in Abari.

On TheCable’s visit to the community, these ruins were not difficult to locate as parts of damaged houses, broken walls, and woods that are yet to be completely submerged dotted the river edges.

Advertisement

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in its sixth assessment report, stated that in West Africa particularly, there has been an upward trend in hydrological extremes in the last few decades and this has caused increased flood events in riparian countries of rivers such as Niger.

Climate change is causing an increase in precipitation, causing the River Niger and its tributaries to overflow and encroach into communities like Abari.

Meanwhile, people like Agidi are left to suffer the consequences. When he returned home after years of working in Lagos, Agidi said he was struck with an unexpected reality. Home, as he used to know, was different.

Advertisement

His parents’ house was the first to be submerged; this made Agidi go farther into the community to build a new house. But little did he know that he would also lose that house to flooding and would need to build another one where he now lives. As though followed by the waters, Agidi’s current house is also being threatened by the same challenge.

“I cannot plaster this house because the [flood] may wash it away tomorrow; so, what is the need? The [river] is now very close to my house. It has eroded all our houses,” he said.

‘WE’RE FINISHED’

About ten meters away from Agidi’s house, 84-year-old Esther Akpeti raised her hands in the air, shaking them frantically in bewilderment. “We are finished o!” she wailed. “The river is taking our lives and hopes with it.”

Advertisement

As a young woman growing up in the community, Akpeti said she used to visit the river to bathe.

“Those days, before I trek from the river to this place, all the water on my body would have dried up and I’d be covered in sweat,” she said. But now, the river is almost at her doorstep.

“People don’t want to build houses here anymore because some houses have been buried in the middle of the river. Our children can’t build houses. Even my father’s house is now in the middle of the river. These days, we try to make do with mud and makeshift houses so that when the water takes it, we won’t feel it,” Akpeti said.

She lamented that her grandchildren will grow to meet Abari in ruins – that is if there still remains a place called Abari. “We’ve been crying but we haven’t been heard. I pray God touches the government to hear us,” she submitted.

Advertisement

About 100 kilometers away from Abari, 50-year-old Susan Jonathan is someone else who feels her life is “finished” as a result of the flooding in her community – Obuguru in Ogulagha Kingdom, Burutu LGA of Delta state.

The oil-rich Kingdom, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean, is situated along Nigeria’s 850km long coastline – which is home to over thirty million people who earn a living from marine resources. But with the continued ocean incursion, lives, properties, and livelihoods are being threatened.

Advertisement

While speaking with TheCable, Sussan had worry written all over her face as she pointed to her house on the verge of submersion. The mother of four fears for her children because the house they live in is barely five meters away from the river. The tides have carved out soil from underneath her house exposing its foundation, so Susan had to use sandbags to support the house to prevent it from collapsing.

“We have been suffering here,” she said. “Most times my children fall sick because the water comes into our home and getting them to the hospital is usually difficult because there is no access road. We don’t have anywhere to go. We need the government to help us.’

Advertisement

Abraham Ebitimi was digging the soil and placing wood planks in it when TheCable approached him. He said he was laying the wood pile as a prevention mechanism for his house and children’s safety. He said his kids constantly fall sick as a result of the waves hitting their homes when the tide is high. He also fears that if care is not taken, his children could be swept away by the ocean.

MORE HOUSES TO GO UNDERWATER AMIDST INACTION

Advertisement

According to the World Bank, up to 41 million Nigerians are living in high climate exposure areas, with some of the highest exposures concentrated in coastal areas like Delta state. It also predicted that by the end of the century, an estimated 27 to 53 million people in Nigeria may need to be relocated due to a 0.5-meter increase in sea level.

This statement is not far-fetched as a good number of people in Abari and Ogulagha are already in need of relocation.

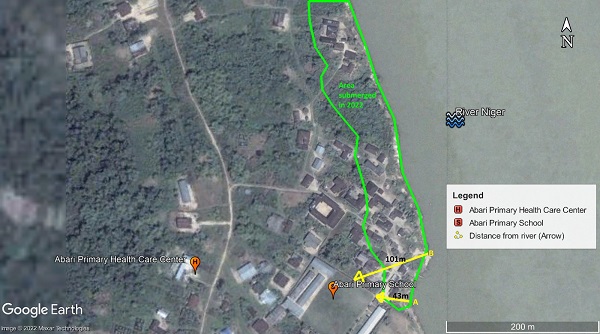

Geospatial analysis, as seen above, showed that in 2006 (Plate 1) Abari community primary school was about 43 meters away from the edge of the river Niger tributary; but now, it is only 11 meters away. This means that within 16 years, a total of 32 meters of land had been lost within the stretch of Abari community (see Arrow A). At another angle from the school (see Arrow B), a total of 58 metres have been submerged.

The analysis also showed that from December 2006 (see Plate 1) to April 2022 (see Plate 2), a total of 28 buildings were submerged (see submerged buildings represented with red polygons), in a community that has about 141 residential buildings. This implies that 20 percent of the buildings in the community have been buried underwater.

The flooding has displaced no less than 168 residents of the community, going by National Bureau of Statics (NBS) survey that there is an average of six persons per household.

The projection from this analysis is that, if the flooding continues at the current pace, by the year 2038, about 50 percent of Abari community, including the only community primary school, will be submerged and many more residents sacked.

Other communities along the tributary such as Ukpo (Plate 3 and 4) which is 34km north of Abari have also lost a great deal of land to the flooding. Failure to act on these climate disasters, according to the World Bank, could cost Nigeria between US$100–460 billion by 2050.

HYDROLOGICAL EXTREMES CAUSING DISPLACEMENTS

In its 2021 state of the climate report, the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) stated that high water stress is estimated to affect about 250 million people in Africa and is expected to displace up to 700 million people by 2030.

Back at Abari, a lot of people currently do not have lands of their own, either for farming or for building. Forty-seven-year-old Paul Epe, an indigene of the community, has left his future to hope.

When Epe’s house collapsed into the river, he was left with no house or land to build, so he relocated out of the community. Epe’s children no longer visit the community because, to them, Abari is no longer home.

“This (river flooding) has done the worst to us, I cannot even wish this upon my enemies. What we wish to have now is a better tomorrow, we need help to get back our community to where people can actually dwell,” he said.

Amos Narene, who lost three houses to the coastal flood in Ogulagha kingdom, currently does not have a house of his own and has sent his children away to live with his sister in another community.

He recalled the night he made the decision to part with his family. It was 2020 and it was late in the night, he said. “We were sleeping and by morning before 6 am, we saw ourselves floating on top of the water. The foam and every property were already soaked. Not long after that, the entire house sank into the sand,” Amos said.

DISPLACEMENTS COULD BREED CONFLICT

Roshanka Ranasinghe, a professor of climate change and coastal risk, said things could get worse going by the IPCC sixth assessment report projections of hydrological extremes in West Africa.

“For Africa, under river flood, the IPCC AR six stated there is medium confidence of upward trend in flood event occurrences. That means that the occurrence is increasing more. And in particular, West Africa, upward trends in hydrological extremes such as maximum peak discharge have likely occurred during the last few decades,” the professor said.

“So, what we can understand from this is that the flood discharges have likely increased in the last few decades after 1980. At the same time, they are also occurring more frequently. So, that could be one reason why these communities that are very close to the river bank are getting flooded more often.

“But also worrisomely, it also says for the future, specifically in West Africa, under the highest emission scenario of regional climate prediction (RCP) 8.5 there is medium confidence of increase in flood magnitudes by 2050 in countries within the Niger River Basin. So, it can get worse.”

Olumide Onafeso, a physical geographer and senior lecturer at Olabisi Onabanjo University, said if the surge continues in these areas that have no ocean protection or mangrove vegetation, “by 2029, at least one kilometer, that is an area of about 10 football fields, would have been affected.’’

For Kentebe Ebiaridor, programme manager, Environmental Rights Action/ Friends of the Earth Nigeria (ERA/FoEN), Port Harcourt office, he is concerned that displacements as a result of flooding could lead to resource struggle between communities and thus breed conflict in the Niger Delta.

‘’Conflicts are already happening in little bits in different parts of the Niger Delta. If you look at most of the conflicts, it deals with land and then you ask yourself, why are these people fighting over land?’’ he said.

‘’It’s about survival and they need to have somewhere to call their own. It may look little right now, but I assure you in less than ten years it will be full-blown conflict.’’

RESIDENTS COMPLAIN AMID LACK OF FUNDS

John Bebapere, chairman of Ogulagha, said his community has been complaining to government authorities but has not seen any action. He mentioned that in some parts of the kingdom, the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) has done an ocean embankment which was “not-so-good”; and from what TheCable observed, this embankment is now also gradually giving way into the water.

In Abari, the tale is not different. Abraham Zituboh, chairman of Abari, complained that on several occasions, government agencies have come to survey the area but no intervention was seen afterward.

‘’In 2017, NDDC consultants came here to do serious survey work and said they would do ocean protection for us. They said they were waiting for approval to award the contract. We were very happy. But to our greatest surprise, nothing happened since then,’’ he said.

On its part, the NDDC said it doesn’t have enough funds to carry out some of its planned projects.

Onuoha Obeka, NDDC director of project monitoring and supervision, said aside from the funding challenge, the dynamic nature of the shoreline was such that the concepts they earlier proposed for some of the projects did not deliver a good job. So, the NDDC is revising some of the methods for other workable alternatives.

“Some of the initial concepts that we had proposed at some point didn’t quite do the great job that we had intended and so we are also revising some of the methods to more plausible alternatives. That’s on one hand. These are technical issues that we are dealing with,” He told TheCable.

“I would also like to let you know that we also have a budget cap, and our project size is increasing year in and year out. So, the lean resource that we have is not adequate to cater to all the projects that we have actually undertaken to solve the environmental problems of the Niger Delta. Largely, I will say that we have a funding challenge.”

He added that in the meantime, the government at all levels as well as ministries and agencies should collaborate with the NDDC to address these challenges as well as relocate and resettle the residents of these communities.

As floods continue to ravage many Nigerian states yearly, someone like Agidi hopes that help comes soon enough. As an elderly and ailing man, he told TheCable that if anything happens to his current residence, he would be too weak to escape for his dear life.

The geospatial analysis was done by Chukwudi Njoku, a geographic information systems consultant.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by OSIWA.

Add a comment