A house that previously had part of its roof blown off

Ruth Ajayi, a 45-year-old pepper seller, has always lived in Ushafa, a suburb in the Bwari area of Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital territory. In this clustered environment, houses are so closely knit that one can barely spread out two arms in some corners.

Ajayi, a widow, relies on her small-scale pepper business to put her children through school. But while she struggles to make just enough to feed her family and pay school fees, something else greatly troubles her as the rainy season sets in – the windstorm.

Yearly, Ajayi and her neighbours contend with the raging wind which leaves destruction and loss in its wake.

“Whenever the wind comes, it takes everything with it,” she said. “Our zincs, our antenna poles. We usually try to use large stones to hold the zinc.

Advertisement

“Once the rainy season comes, that is when it becomes intense. We always try to stay inside.”

Whenever her roof goes off, Ajayi spends between N10,000 and N20,000 to repair the damaged parts.

Elizabeth Obed, a 41-year-old civil servant and neighbour of Ajayi, would have been recounting her ordeal of loss if an electric pole brought down by the windstorm had not missed her house by an inch.

Advertisement

She remembers the day vividly and counts herself lucky that the windstorm which accompanied the rain did not bring forth havoc on her household.

Natural disasters like the one experienced in Ushafa have been linked to climate change. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), with the increasing global surface temperatures, the possibility of increased intensity of storms will likely occur.

This is because as more water vapour is evaporated into the atmosphere, it becomes fuel for more powerful storms to develop.

DEFORESTATION, FIREWOOD BUSINESS A CONTRIBUTORY FACTOR

Advertisement

The recurring incident in Ushafa has not always been a norm. Ajayi and Obed said they noticed that the intensity of the wind took a different twist about five years ago.

Ajayi said the change became more prominent when the trees in her community were cut down to make way for buildings and development in the area.

“We used to have a lot of trees in this area but as more people moved here and people bought lands and built houses, they also tried expanding the road and they cut down everything and that’s why we don’t have trees here,” she said, adding that “when we had trees, the wind was not this terrible”.

Research by Greenpeace Research Lab shows that complete tree removal causes an increase in wind speed and air temperature. The report said deforestation has the potential to disrupt weather and climate systems on a local, regional and global scale.

Advertisement

But despite fears that the removal of trees in their environment could be part of their woes, several Ushafa residents use fuelwood for cooking and also engage in its sale.

Right in front of Obed’s house was firewood numbering over 200 pieces stacked up against the fence. She said she bought them for N30,000 and they could last her for a year, adding that they are more viable than gas – which is considered a cleaner energy source.

Advertisement

Residents like Jumai Danladi, who is in her 60s, rely on the firewood trade to make ends meet. Danladi once lost her outdoor kitchen to the windstorm, but with nothing else to do for money, she will continue to patronise those who cut down trees for firewood.

TREES – A MAJOR ELEMENT OF URBAN PLANNING

Advertisement

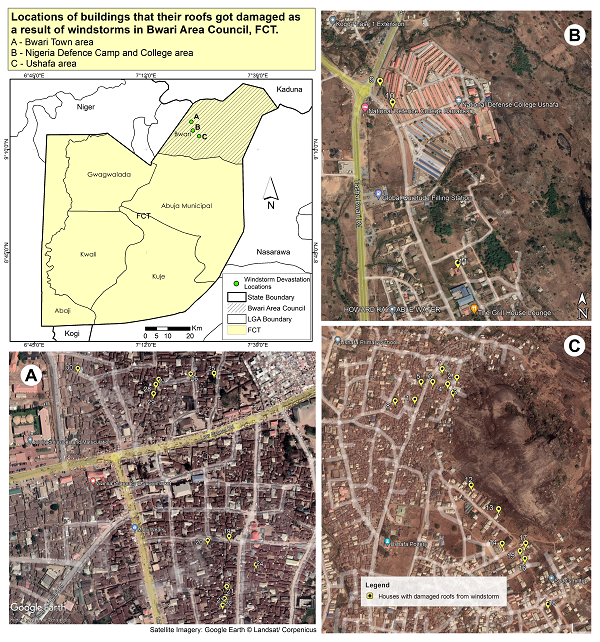

The map below shows the locations of over 30 houses that had parts or their entire roofs removed as a result of the windstorm in Bwari. The locations visited were marked as A, B and C.

A field visit and an examination of the satellite imagery of the area also showed that there were insufficient trees that would have served as windbreaks in the environment.

Advertisement

The most affected areas were also remarkably of low housing quality – some were made from zinc and wood while the houses built with cement were unfortified.

The Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) has recommended that trees need to be inculcated into urban planning. This is because urban forests – which include individual trees found in streets and parks in urban and peri-urban areas – help to reduce the risk of natural disasters like the one experienced in Ushafa. The agency also said the presence of trees could support climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies.

Amedu Richard, director of works, Absans Homes Ltd, said trees are always encouraged in urban planning because they serve as a buffer against windstorms.

He said despite having a good blueprint, the lack of adherence to planning standards in some parts of the FCT has brought urban environmental issues such as floods, windstorms and other natural disasters.

“In urban planning, trees stand in as windbreakers, so lack of it means the area will suffer the effects of wind storms just like in desert areas, which is the reason why we encourage buffer zones in all our layout designs,” Richard said.

“Windstorms are only experienced in areas with limited windbreakers (trees), meaning these areas complaining about such disasters are also culpable by their own practices of trees felling without replacement for economic gains and development. I will advise them to desist from such actions and start planting trees so as to prevent future disasters.”

COULD CLIMATE CHANGE BE DRIVING INCREASED WIND SPEED?

A report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released in August 2021, suggests that wind patterns might be a viable warning sign in predicting climate crises. The report projects that wind speed is likely to either increase or decrease depending on the region. The report also mentioned that “peak wind speeds of the most intense tropical cyclones are projected to increase at the global scale with increasing global warming”.

Therefore, experts believe that as climate change persists, there is a need for more intentional monitoring and mitigative measures to forestall resultant natural disasters.

Chukwudi Njoku, an environmentalist, said although the science of this phenomenon is not yet entirely clear, recent global trends with wind-related disasters show that climate change could be fueling an increase in windstorms.

“It proves to be difficult to entirely link increasing wind gusts to climate change alone because the wind speed is influenced by other factors such as topography, atmospheric forces driven by air temperature differentials over land and sea, and others,” Njoku said.

“However, an increase in the global average wind speed by about 0.4 kmh in the past decade points to the fact that another factor – climate change may be driving the changes. The linkage can be buttressed with the recent increase in wind-related disasters also such as hurricanes, wildfires, tornadoes and wind gusts at local scales.”

He said more research needs to be carried out in the Nigerian context to gauge the intensity at which the wind has increased over the years, the causes of the increase and if there is any cause for alarm.

Meanwhile, Njoku believes that Nigerian communities are most impacted by climate change because they are not resilient enough to withstand the impacts of climate change.

He said Nigeria needs to intentionally build resilient cities, ensure proper infrastructure in communities, plant and preserve trees to serve as windbreaks and significantly mitigate disasters such as windstorms.

Njoku advised that while it may be difficult for Ushafa residents to properly adapt, by having resilient building infrastructure, they should intentionally invest in tree planting which could serve as a “viable alternative and natural windbreaks”.

As more rains are expected in the coming months, Ajayi has begun praying that “God holds the building so the wind doesn’t take down our houses”.

This report was produced under the 2022 Dataphyte fellowship

Add a comment