The past weeks in the Nigerian media space have been laced with discussions, dissections, and disagreements over the establishment of Sharia arbitration panels in south-west states.

The controversy began in December 2024 when the Oyo state chapter of the Supreme Council for Shariah in Nigeria initially announced plans to establish a sharia court in the state and its environs. The event was scheduled to take place on January 11, 2025, at the Muslim Community Islamic Centre, Oba Adeyemi High School road, Mobolaje area of the state.

The announcement was received with reservations, and following the backlash that trailed it, the council suspended the event indefinitely. The council further said its announcement was misconstrued, and that what it intended was the establishment of independent arbitration panels to resolve family disputes among Muslims.

The issue became heightened with the first sitting of the panel in Ekiti and the subsequent statement by the state government that the judicial structure of the state does not allow for Sharia courts or panels.

Advertisement

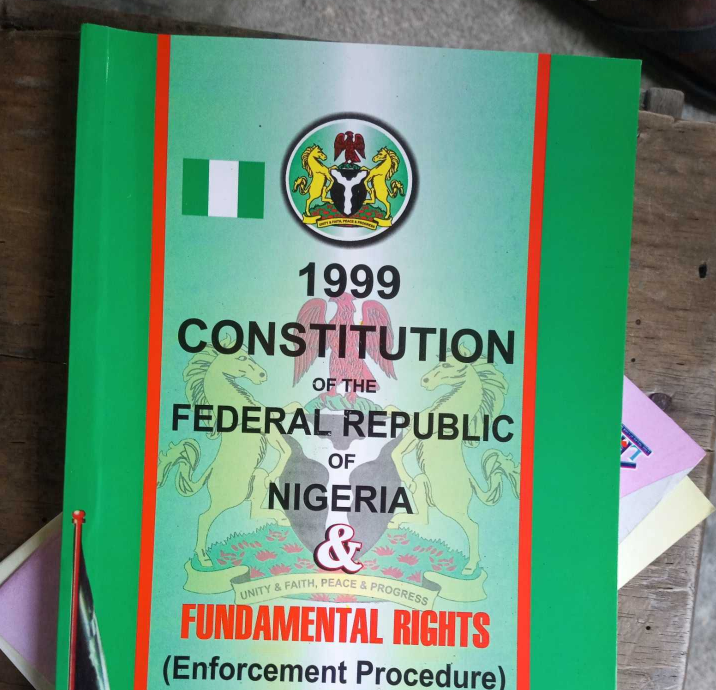

Nigeria’s legal system is a fusion of common law, customary law, and Sharia (Islamic) law, reflecting the country’s ethnic and religious diversity.

The constitution provides a framework for the establishment and practice of Sharia and customary laws, particularly in civil matters.

This explainer outlines the constitutional provisions governing the Sharia system and the controversies surrounding its implementation.

Advertisement

DOES THE CONSTITUTION RECOGNISE SHARIA LAW?

The simple answer is yes.

Sections 275 and 277 of the 1999 constitution as amended create a clear legal basis for the creation and existence of Sharia courts. These sections allow states to establish Sharia courts of appeal to adjudicate matters concerning Islamic personal law.

“There shall be for any State that requires it a Sharia Court of Appeal for that State. (2) The Sharia Court of Appeal of the State shall consist of – (a) a Grandi Kadi of the Sharia Court of Appeal; and (b) such member of Kadis of the Sharia Court of Appeal as may be prescribed by the House of Assembly of the State,” section 275 reads.

Advertisement

The section further prescribes the process and requirements for the appointment of the Kadis.

This means that while the constitution permits states to establish Sharia courts of appeal, it does not mandate them to do so. The decision rests with individual state governments, based on the needs of their Muslim populations.

The constitution does not, however, specify on what conditions a state may require the establishment of a Sharia court.

Currently, thirteen northern states — Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Niger, Sokoto, Yobe, Zamfara, and Kwara — have Sharia courts of appeal.

Advertisement

In addition to state-level courts, the federal capital territory (FCT), Abuja, has both a Sharia court of appeal and a customary court of appeal as provided for in sections 260 and 265 of the constitution, respectively. These federal courts function as appellate courts for cases originating from lower Sharia and customary courts within the FCT and serve as models for states that may wish to establish similar judicial structures.

WHAT IS THE JURISDICTION OF SHARIA COURTS?

Advertisement

Muslims have the constitutional right to seek adjudication under Sharia law for civil matters.

Though Sharia law is legally backed, its application must remain within the limits set by the constitution, ensuring that it is voluntary and does not infringe on the rights of non-Muslims.

Advertisement

Section 277 of the constitution allows Sharia courts to hear matters that mainly deal with Islamic personal law issues related to marriage, family, inheritance, and guardianship, provided that the parties involved are Muslims.

Section 277 reads: “The Sharia Court of Appeal of a State shall, in addition to such other jurisdiction as may be conferred upon it by the law of the State, exercise such appellate and supervisory jurisdiction in civil proceedings involving questions of Islamic personal law which the court is competent to decide in accordance with the provisions of subsection (2) of this section. (2) For the purposes of subsection (1) of this section, the Sharia Court of Appeal shall be competent to decide – (a) any question of Islamic personal law regarding a marriage concluded in accordance with that law, including a question relating to the validity or dissolution of such a marriage or a question that depends on such a marriage and relating to family relationship or the guardianship of an infant; (b) where all the parties to the proceedings are muslims, any question of Islamic personal law regarding a marriage, including the validity or dissolution of that marriage, or regarding family relationship, a foundling or the guardianship of an infant; (c) any question of Islamic personal law regarding a wakf, gift, will or succession where the endower, donor, testator or deceased person is a muslim; (d) any question of Islamic personal law regarding an infant, prodigal or person of unsound mind who is a muslim or the maintenance or the guardianship of a muslim who is physically or mentally infirm; or (e) where all the parties to the proceedings, being muslims, have requested the court that hears the case in the first instance to determine that case in accordance with Islamic personal law, any other question.”

Advertisement

It is important to note that Sharia courts of appeal, like customary courts, do not have jurisdiction over criminal cases under the Nigerian constitution. However, several northern states have expanded the application of Sharia law to cover certain criminal offences like theft and blasphemy through state legislation.

Also, Sharia and customary courts can only be constituted by state governments, not individuals or groups.

THE CONTROVERSIES

While northern states have widely embraced Sharia law, many southern states, particularly in the south-west, have been reluctant to establish Sharia courts of appeal. This has led to ongoing legal and political debates about religious rights and the constitutional provisions of Sharia law.

On Wednesday, the Nigerian Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs (NSCIA) said the arbitration panels were conceived to fill the vacuum of Shariah courts of appeal in states where they have not been established “despite constitutional provisions allowing them”.

The council, led by Sa’ad Abubakar, Sultan of Sokoto, alleged that the rejection of the arbitration panels shows a broader pattern of discrimination against Muslims in the region.

Meanwhile, the Ogun state government has also joined in the disapproval of the constitution of Sharia courts or arbitration panels in the state.

Dapo Abiodun, the state governor, in a statement signed on Tuesday, said the Sharia court does not form part of the legal framework operating in the state.

“The Ogun State Government has noted the circulation of a digital notice announcing the launch of a Shari’ah Court in Ogun State,” the statement reads.

“No Sharia Court is authorised to operate within Ogun State. The courts that are legally empowered to adjudicate disputes arising within Ogun State are those established by the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria or by State Laws, which are: Magistrates’ Courts, High Court, Customary Courts, Customary Court of Appeal, Federal High Court, National Industrial Court, Court of Appeal, and Supreme Court.

“No law operating in Ogun State has established a Sharia Court, and Sharia law does not form part of the legal framework by which the Ogun State Government administers and governs society.”

Ultimately, the Nigerian constitution upholds Sharia and customary laws as integral to the country’s legal system. However, their practical implementation remains subject to political, religious, and cultural considerations, with debates likely to continue over how best to balance religious freedom, legal uniformity, and constitutional rights.

Add a comment