Distribution of free walking aids to sickle cell patients at the National Sickle Cell Centre in Lagos

One in four Nigerians are carriers of the sickle cell gene. Nigeria has the highest number of sickle cell patients, making the country the epicentre of the disease in the world. It is the most populous country in Africa and over 40 million residents are carriers of the sickle cell gene.

Out of the 300,000 babies born with sickle cell disorder around the world every year, an estimated 150,000 babies are from Nigeria. Unfortunately, 100,000 of the SCD babies in Nigeria do not live up to the age of five owing to ignorance and a lack of access to proper diagnosis and care. These statistics provided by the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria are grim. It makes the heart palpitate. But it is a bitter reality.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of inherited red blood cell disorders. Red blood cells contain haemoglobin, a protein that carries oxygen. Healthy red blood cells are round, and they move through small blood vessels to carry oxygen to all parts of the body.

“In someone who has SCD, the hemoglobin is abnormal, which causes the red blood cells to become hard and sticky and look like a C-shaped farm tool called a “sickle”. The sickle cells die early, which causes a constant shortage of red blood cells. Also, when they travel through small blood vessels, they get stuck and clog the blood flow. This can cause pain and other serious complications (health problems) such as infection, acute chest syndrome and stroke,” the CDC stated.

Advertisement

The complications include pain, stroke, acute chest syndrome, leg ulcers, infection, blood clots, anaemia, avascular necrosis, organ damage, and a shortened life expectancy. Being born with a sickle cell disorder causes suffering for a lot of patients and their families. The pain crisis often comes with discomfort and an emergency response to save the lives of the patients.

The treatment and management of sickle cell disease involve the use of drugs and blood transfusions – from pain-relieving drugs to supplements, penicillin to prevent infections, and hydroxyurea.

Before now, the only approved cure for SCD was a bone marrow or stem cell transplant, which comes with high risks and serious side effects, including death. The procedure involves taking healthy cells that form blood from one person, a healthy donor, who is often a sibling, and putting them into the patient. The stem cells then begin to create healthy red blood cells to replace the sickle cells.

Advertisement

Despite its risks, the procedure has recorded many successes across the world. On September 28, 2011, Nigeria recorded the first successful bone marrow transplantation — the third in Africa after Egypt and South Africa. Godwin Bazuaye, a professor of haematology, and his team performed the procedure at the University of Benin (UBTH) Teaching Hospital on 7-year-old Ndik Matthew, who had a stroke and paralysis. His elder brother was the donor.

THEN COMES THE ADVANCED CURE: GENE-EDITING THERAPY

In November 2023, the United Kingdom approved Casgevy, a gene therapy for the treatment of sickle cell disease. While a bone marrow transplant requires a donor, gene therapy doesn’t. In the new treatment, which uses the gene-editing tool CRISPR, patients’ stem cells are collected, modified, and injected back. During clinical trials, 28 out of 29 SCD patients were reported to be free of severe pain.

Julian Beach, interim executive director of healthcare quality and access at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), said the gene-editing technology was “found to restore healthy haemoglobin production in the majority of participants with sickle-cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassaemia, relieving the symptoms of disease”.

Advertisement

In December, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Casgevy and Lyfgenia, becoming the first cell-based gene therapies for the treatment of SCD in patients 12 years of age and older.

“Gene therapy holds the promise of delivering more targeted and effective treatments, especially for individuals with rare diseases where the current treatment options are limited,” Nicole Verdun, director of the Office of Therapeutic Products at the FDA, said.

According to Yale Medicine, the two treatment procedures require high-dose chemotherapy to kill the faulty stem cells. It says Casgevy, an edit (or “cut”), is made in a particular gene to reactivate the production of fetal hemoglobin, which dilutes the faulty red blood cells caused by sickle cell disease, while Lyfgenia, on the other hand, uses a viral envelope to deliver a healthy haemoglobin-producing gene.

The cost of Casgevy and Lyfgenia is estimated at $2 to $3 million per patient.

Advertisement

In Nigeria, the nation with the largest burden of SCD in the world, the cost implications are quite massive and unimaginable.

According to the 2022 Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) survey of the National Bureau of Statistics, the number of Nigerians living in poverty stood at over 133 million, representing 63 per cent of the nation’s population. This means over half of the population of Nigeria is multidimensionally poor. The majority of these poor people, according to the survey, are deprived of clean cooking fuel, adequate sanitation, and access to good healthcare.

Advertisement

With the rising standard of living and economic hardship the majority of the citizens are currently facing, gene therapy seems like a pipe dream. Hence, the announcement of the new therapy did not elicit the expected excitement from the country where SCD is a major genetic condition.

‘IT’S A BITTER-SWEET STORY’

Advertisement

In an interview with TheCable, David Ajibade, the medical director and founder of Brain and Body Solutions, Ltd., an integrated health centre in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, said that although the approval of the new therapy offers hope to the SCD community, Nigeria currently lacks the infrastructure for widespread gene therapy delivery.

The medical doctor said the pace of advancement in gene therapy globally outstrips current capabilities in Nigeria, which limits the immediate benefits for most Nigerian patients.

Advertisement

“The approval of gene therapy for SCD is undeniably groundbreaking news, offering a potential cure for a disease previously considered incurable. However, for the Nigerian SCD community, it’s a bittersweet story. While it sparks hope, there are significant hurdles to access and affordability,” Ajibade said.

“For instance, this treatment currently costs $2 million. This does not include ancillary healthcare, including investigations, nursing care, follow-up, etc. This is simply out of the reach of most Nigerians.

“Gene therapy offers immense hope, but accessibility in Nigeria is uncertain. Several factors complicate its arrival. An estimated $2 million per treatment is exorbitantly high. Even with subsidies, affordability remains a major barrier. This highlights the harsh reality of healthcare disparities and emphasizes the need for equitable access within the country.

“Even existing treatments (hydroxyurea) are often out of reach for many patients. Rising living costs and high drug prices make access to essential medication a constant struggle. The situation is dire, and gene therapy, at its current price point, further widens the gap.”

On her part, Ayomide Olanipekun, a medical doctor and executive director of OA Initiative, a community-focused non-governmental organisation, said the newly approved drugs offer hope to those seeking bone marrow transplants but are facing challenges in finding a donor match or coping with associated complications.

The genetic counsellor added that the high cost of the treatments presents a significant hurdle, but addressing affordability through government support, insurance coverage, and potential price negotiations will be crucial to making the treatment accessible to the wider community.

“When I heard the news, I was genuinely happy, as it felt like we were finally making progress. However, this excitement was short-lived when I saw the price. I can vividly recall the day it trended on X, and I witnessed numerous reactions from Nigerians, especially sickle cell warriors, including those in my sickle cell community on WhatsApp. Many expressed hopes that, at last, there might be a cure,” Olanipekun told TheCable.

“I believe this development has brought hope to the Nigerian SCD community, demonstrating that they are not forgotten. The narrative is evolving. It’s no longer ‘there is no cure’, but ‘the cure is expensive’. Even though the price is disheartening at the moment, I am optimistic that affordability for the average person is achievable, but it will take time.

“Considering long-term management costs, affordability remains a major hurdle. This results in continued suffering and high mortality rates among low-income families disproportionately affected by SCD.”

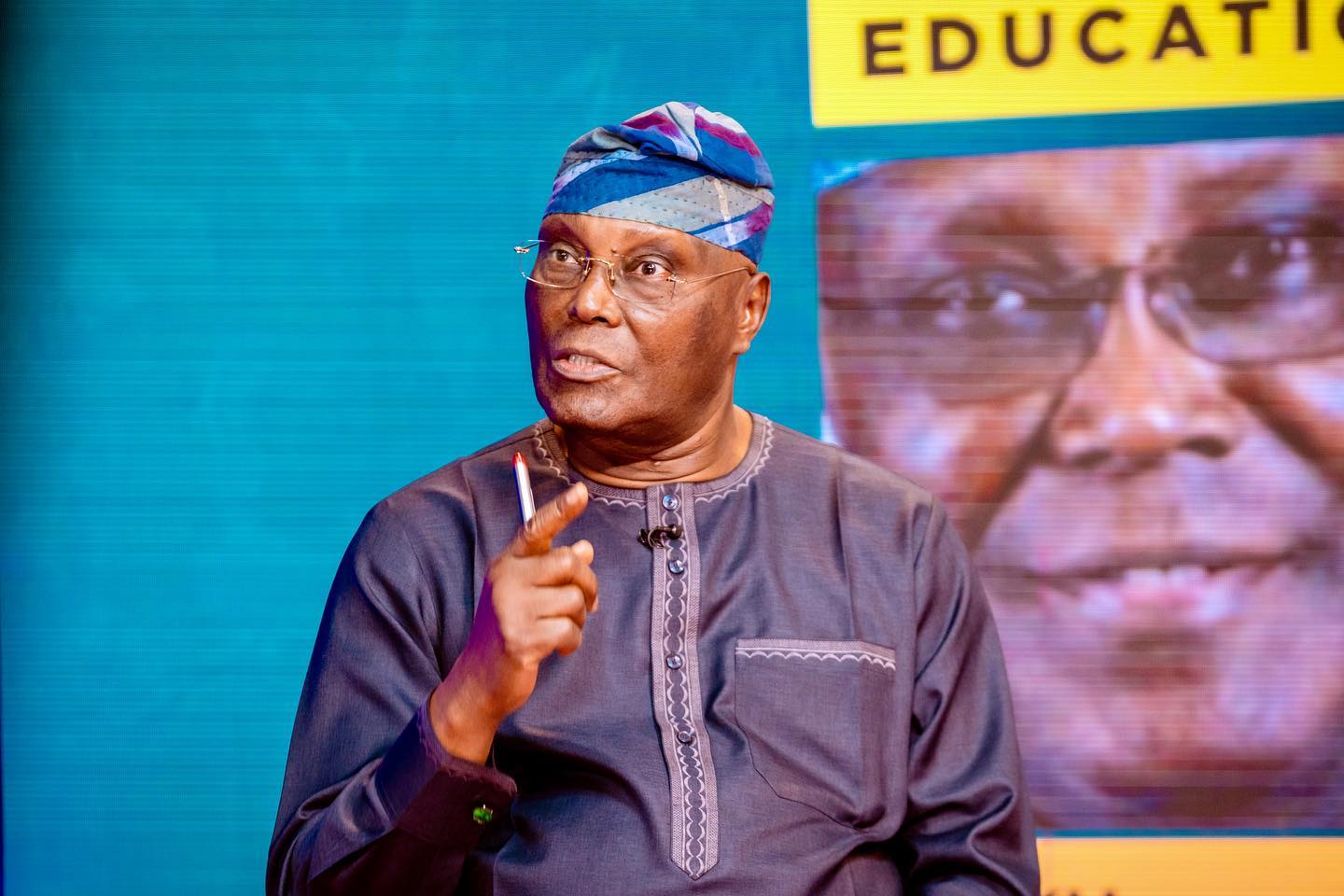

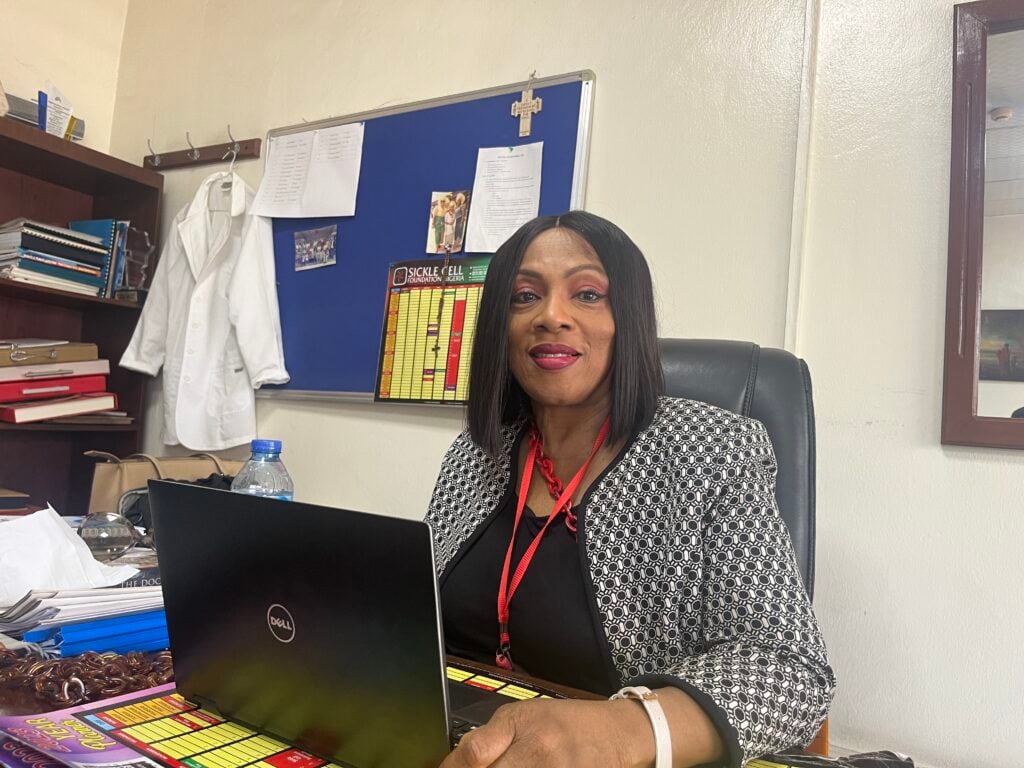

Speaking on the development, Annette Akinsete, chief executive officer of the Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria (SCFN) at the National Sickle Cell Centre, said the organisation is ready to provide access to gene therapy for its patients, but the priority at the moment is comprehensive care to manage the disorder.

She noted that the organisation has already provided some awareness on gene therapy to its clients, to let them know that more is happening in the sickle cell space.

“They need to have hope. The idea is to give them hope and to show them that there is light at the end of the tunnel;” Akinsete told TheCable.

“Two Nigerians are being considered for gene therapy as part of the study in the US. They won’t pay for it. A lot of people can now access it in the US and UK, but it costs millions of dollars and pounds. We are open to getting our patients access to the new treatment. Before, we wanted to act as soldiers, blocking and protecting our patients from anybody who would do anything to them.

“Now, we want to ensure our patients have better treatments from other parts of the world. But we check that nothing bad is done to them, that will make them ill, taken for granted, or used.

“I won’t think about gene therapy as the first cure for my patient. I believe that Nigeria, being the country with the highest burden, should still have that service at the apex of the pyramid. No matter how expensive it is, some people might still be able to afford it. You never know. Let it be available. The government has money. The government should pay for its citizens. Sickle cell patients who qualify for this treatment are very few.”

Akinsete noted that it is not yet certain when the new treatment therapy will be available for the Nigerian SCD community; hence, the focus at the moment is on bone marrow transplants. She said a new facility has been built at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital, which is set to open for bone marrow transplants by March.

“Let’s be realistic. We are still struggling with bone marrow transplantation. Let’s get it off the ground. Let’s get comfortable with it. We are not blocking the road for new technology,” she said.

WILL INVESTMENT IN HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE BRIDGE THE GAP?

As far as investment in the health sector is concerned, Nigeria is lagging. Despite the African Union’s 2001 Abuja declaration to allocate at least 15 per cent of annual national budgets to the health sector, only about five per cent of Nigeria’s 2024 budget was set aside for the health of its over 200 million citizens.

Ajibade said Nigeria currently lacks the infrastructure for widespread gene therapy delivery. He noted that building capacity will require establishing treatment centres equipped with advanced technology and trained personnel, developing regulations and safety protocols for gene therapy applications, and fostering local research and development to adapt and optimise therapies for the Nigerian context.

“Building the infrastructure for gene therapy delivery requires significant investment and expertise. Transporting and storing specialised therapies require robust cold chain systems. Therefore, while it holds promise, widespread access in Nigeria is likely years away,” Ajibade said.

“Several approaches can help Nigeria bridge the gap. Negotiating affordable drug prices, implementing health insurance coverage for gene therapy, raising public awareness about SCD, and advocating for more simple, more accessible treatments.”

For Olanipekun, implementing gene therapy in Nigeria is feasible but requires commitment from the government, healthcare providers, and research institutions.

“Collaboration is key to addressing infrastructure development, cost reduction, and equitable access. Exploring partnerships with international entities and leveraging existing initiatives can accelerate progress, potentially happening sooner than expected,” she said.

“We must advocate for government investment in infrastructure, healthcare access, and research partnerships to bring down treatment costs. Also, engaging the private sector to address societal stigma and ensure employment opportunities for SCD patients is crucial. By working together, we can bridge the gap and ensure Nigerian patients benefit from these lifesaving advancements.”

This story was produced as part of the 2023 Rare Disease Reporting Fellowship of the National Press Foundation (NPF).

Add a comment