Nigeria faces a myriad of economic troubles: unemployment driving brain drain, climbing poverty numbers, strained forex reserves, and a revenue shortfall that plays into a ballooning external debt. But more pervasive is the fall in naira’s value, inflation, and a resultant shrink in purchasing power.

As in past attempts to boost forex supply and encourage capital inflows, the CBN has had to devalue the naira, driving up import prices — a measure that should discourage the patronage of foreign goods. However, the limited supply of substitute products to feed domestic demand and cater to increased export potential defeats the gains of devaluation.

Dollar demand to satisfy import needs remains constant and meets a shortage of forex earnings from export revenue. Exchange rate adjustment through devaluation follows — with the naira falling from N155/$ in 2014 to N411/$ in 2021. The imbalance in forex demand and supply keeps devaluation in sight despite its harsh effect on the local economy.

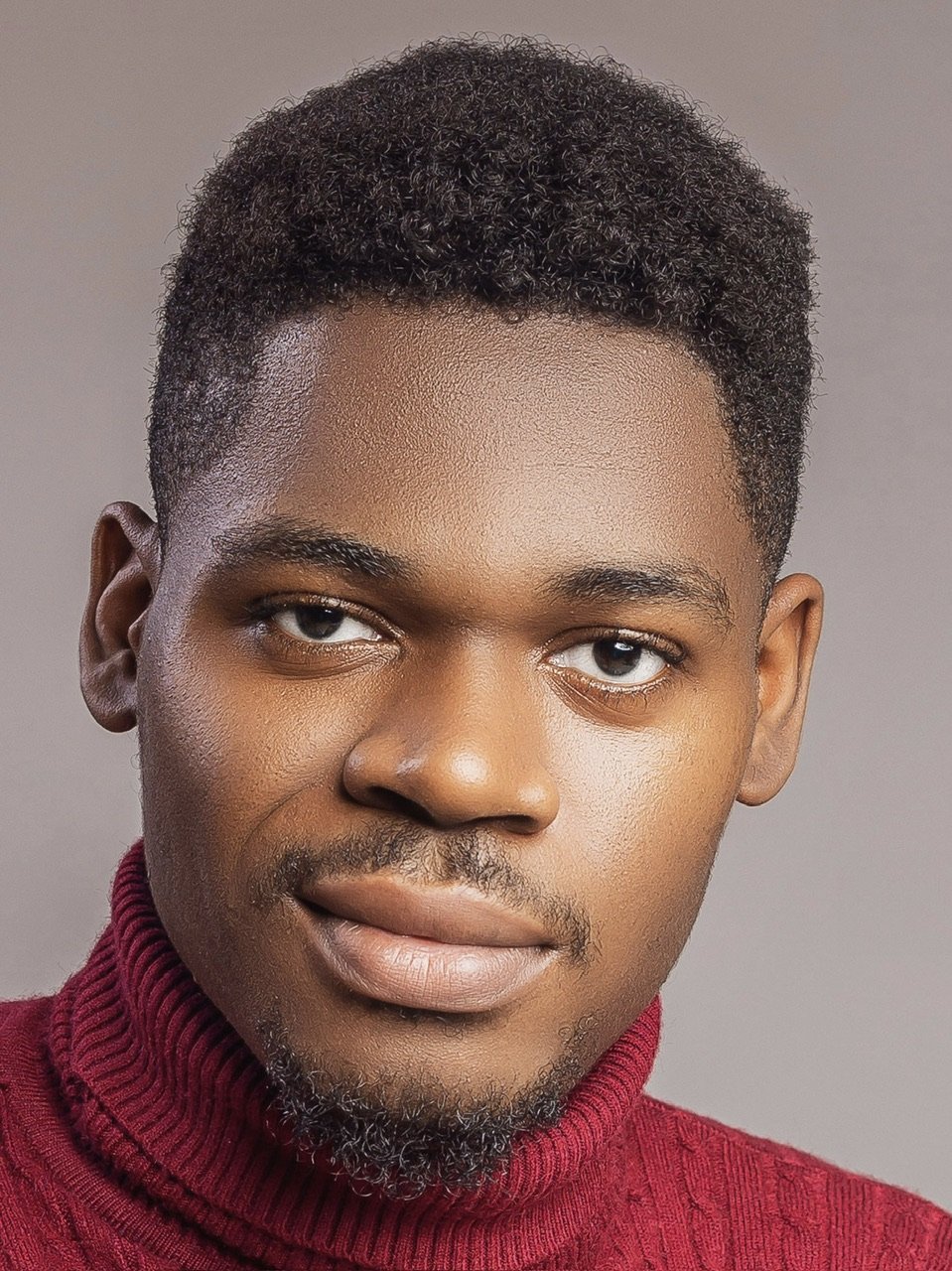

As the naira exchanged for N414 to the dollar in October as against N570 in the parallel market, arguments in favour of devaluation resurfaced. Femi Saibu, a professor of Economics at the University of Lagos (UNILAG), in an interview with TheCable, says any attempt to escalate Nigeria’s currency crisis may herald an economic catastrophe.

Advertisement

You’ve done a great deal of research in development macroeconomics and finance, giving speeches on the African economy across multiple countries. What moment in all of these stands out for you?

My 2012 trip to South Africa, where I joined experts in analysing the African economy to develop perspectives and build a mechanism through which we can see the African economy from local perspectives and work out how we can realise an economy that depends much more on our local resources. We seem to look at the African economy in terms of sales, thereby not exploring our production capacity. We considered opportunities to industrialise Africa. It was a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Johannesburg where I worked with South Africa’s finance experts.

In OAU and UNILAG, you’ve functioned in multiple capacities, partnering with stakeholders at varying levels and rising through the ranks to become a professor of Economics. What was the drive?

Advertisement

My journey to academics was deliberate. After my master’s, I stayed put in the varsity until I was employed. I started in academic life in 2001 when I got employed, at around the same time when I ended my masters. I needed to pursue my Ph.D. which I completed in 2006. With mentorship, I was able to build my capacity and amass experience.

I’ve done research in such areas as public finance, public procurement, international economics and examined how macroeconomic policies can be used to stimulate economic diversification, promote employment, and abate poverty.

What would be your assessment of how Economics is currently taught in Nigerian universities?

The curriculum is too theoretical by design and in the wider context of the system. We tried to see how we could infuse the latest trends in it to allow for pragmatism by ensuring that when we teach, we relate directly with what happens in the corporate world and government. We touched on what is obtainable globally so that the students are able to relate well anywhere they find themselves. I and my colleagues tried to refine the curriculum, taking positions in review committees. In OAU, I was instrumental to the curriculum being used in the Economics department, bringing in new courses that relate practically to the corporate world. I did the same thing in UNILAG.

Advertisement

Today, we have Creative Economics which takes care of entertainment and music. We ensured our students spent six months with a corporate organisation before graduating by introducing Industrial Experience to the programme, which has never happened in Nigeria. This way, many of them hardly find it difficult to get jobs due to the network they built. It helped them identify their skill gaps and level up. The current system, as done by the NUC, isn’t dynamic enough. Attempts by corporate bodies to influence the NUC towards tailoring university curriculum to suit their own needs will not do us any good. Instead, they need to engage with the varsity stakeholders to facilitate the creation of special programmes that can thereafter be applied by the individual because they still need all the skills.

The system can be conservative. What challenges did you surmount to facilitate these changes?

Our programmes need to be at par with global standards but people are always reluctant to accept change. You come with innovative ideas and they start reading meanings to them. With like minds and the support of leaders in UNILAG, we pushed boundaries. You don’t get to a system and complain about the problems you’re supposed to be fixing. I saw most of our problems as challenges that we had to steer to our advantage. And things are getting better.

On November 17, you gave an inaugural lecture to push for a rethink of the development process in Nigeria, touching on budgeting and procurement at the grassroots. What reforms would you suggest?

Advertisement

I used local analogies to explain the kind of policy intervention that Nigeria needs to implement. What I’ve observed is that many of our policies are not driven by needs, circumstances, and capacities. They’re majorly imposed by what some other people believe to be what we need. They interpret our needs and solutions, sell us their ideas, and use the locals to lobby those that call the shots. These policies eventually fail, irrespective of how well they are presented.

In Nigeria, for instance, we have a mass commuting problem. Clearly, we need a mass transit system, yet we let small cars and tricycles operate in the public transport sector. A thousand such on the roads and we end up in a gridlock. What if we explore more big buses that can move people in hundreds? There won’t be traffic! Also, we tend to apply sophisticated interventions for locals who need — not the luxury, but basic necessities. Nigerians need policies that put food on their tables, provide healthcare, give good roads, and put children in schools with a focus on skill acquisition.

Advertisement

They know exactly what they need and are in the best position to provide it —local solutions. But what we have is a situation where we apply solutions used in developed countries; policies designed by people who observe from a distance. Days ago, FG approved the national development plan from 2021 to 2025, which will cost Nigeria about N348.7 trillion of which the private sector will provide over N298 trillion. That’s over N85% of the budget.

I assure you that over 90% of Nigerians weren’t aware when this plan was being developed; 98% didn’t even make an input. I was involved. We met virtually to craft things we thought people in villages need. I’m in Lagos designing policies to develop a village in Zamfara and Maiduguri where I’ve never been. Those in the committee weren’t up to 2,000 in a country of over 200 million. Those relatively comfortable are determining the lives of remote villagers.

Advertisement

What I suggest is that these remote villages come together and determine what they need to develop. What are the immediate needs? How do we provide and fund it? Whatever they agree on, we translate that to the community level. Every town, that way, comes up with what they need. Then we have a town development plan. We sum all that to arrive at an LGA development plan. We arrive at the senatorial district development plan that will make up the state development plan, then the zonal plans. These can then be summed to arrive at the full national development plan.

This way, we take care of everyone’s needs from ground to up, not otherwise. You don’t even need to award contracts because locals will take care of it and ensure infrastructure is secure. We need an inclusive approach to development to ensure there’s a match between needs and procurement. Locals lack electricity but we give them public toilets. They need jobs but we’re erecting solar panels on their streets, even when they don’t have stable power supply.

Advertisement

During the midterm review of President Muhammadu Buhari’s second tenure, VP Yemi Osinbajo said Nigeria needs to move its exchange rate to reflect the market. What’s your take on naira devaluation as an approach to boosting forex inflow and the CBN’s demand management strategy?

It’s good that the VP later argued he never asked for devaluation. Theoretically, exchange rate devaluation is good. No country wants to revalue its currency especially when the economy is globally opened. When your currency is strong, the domestic price of goods is high, you lose the market. People won’t buy from you especially when they can buy anywhere in the world. Most countries try to ensure they have a weak currency so that domestic goods are cheaper, relative to global goods. People buy and they can export more. However, there are conditions that make devaluation effective. Your supply of goods must be exchange-rate elastic. When a currency depreciates and domestic prices fall, your economy should be able to respond by supplying more goods as demand is increasing.

Demand for foreign goods must also be exchange-rate elastic such that, when the price of foreign goods becomes expensive, imports fall. That means people have local alternatives. Export must rise and imports must fall to neutralise the negative impact of the increase in import price. In Nigeria, we export primary products that do not respond to international prices. So, if the exchange rate (dollar price) increases, we can’t produce cocoa within three days or one year and we don’t even have control over the quantity we produce because it’s naturally determined.

As for oil, the price is not determined by us so there are limited ways by which we can respond. All that makes our exports are not price elastic. In our imports as well, because we do not produce most things we need in Nigeria, no matter how expensive things are overseas, we still import relatively the same amount. Both ways, devaluation can’t solve the problem. It can neither induce greater export nor reduce import. Nigeria just needs to ensure we do not do anything that aggravates the exchange rate situation. The current increase only shot up local prices (inflation) which is more than the exchange rate increase. This way, the benefit that would have come from devaluation is eroded.

No matter the argument, devaluation is not for a country like Nigeria. You don’t import policies from countries that have conditions that enable such to work for them. What we need is to keep the exchange rate (dollar price) low, no matter the cost. We don’t have import alternatives and we’re not producing enough to export so that we can respond to the increased demand that comes with devaluing. We have to strike a balance between the cost of an overvalued currency and the welfare benefit for citizens by keeping it strong. We should focus on expanding our domestic production base so that those basic things that constitute the bulk of our imports are instead produced locally.

If we do this and begin to export those things we have a competitive advantage in, the exchange rate will naturally adjust. But for now, any attempt to trigger a further escalation in the exchange rate situation will be catastrophic.

Import substitution and diversification may not exactly produce quick results. How do we treat this crisis with the sense of urgency it deserves while ensuring our solutions are friendly to the local economy?

You can’t have your cake and eat it. There’s pain before gain. If we want to develop Nigeria, we need to direct people to areas where they face the pain now only to reap the benefits in the near future. Today, we’re coming back to talk about diversification. How has the current liberalised system helped us? Even the local industries we had before have been killed because of excessive international competition. We’re getting worse by not doing import substitution.

In the 1980s, Nigeria produced 83 percent of what was consumed. Now, we produce less than 13 percent. We need to expand domestic production. How we do it is something we have to figure out. We can’t keep borrowing the policies of developed countries. We have a strong human capital. FG should empower them and help them form syndicate companies that can produce large-scale goods and services that constitute our imports. By subsidy, the government can ensure these goods are produced at relatively good quality and at a lower price so that people can afford them.

If we have that, we won’t care if the exchange rate hits the rooftops since we buy locally. It will absorb unemployed youths and yield tax that ends up paying off subsidies. We must develop the domestic economy, not by sponsoring SMEs that are into trading, but real industrial entrepreneurs ready to take risks and produce large amounts of goods that we import. If we go this route, exchange rate will fall because imports will fall and lessen the pressure on forex.

On SMEs, many local businesses are struggling to stay afloat. How best do they navigate the currency crisis?

The SME industry is oversaturated and too competitive. All of them do the same thing. Their unit costs are extremely high because we’re duplicating the same businesses. Many of them trade. Those claiming to produce do so at a small scale. Industries are large-scale businesses that achieve a lower unit cost at production level. SMEs as a development strategy may not work in Nigeria because they’re support services that can’t go into high-tech manufacturing. What FG needs to do is create a synergy between SMEs that are similar and form a cluster where they will combine their resources and influence production cost. That’s the only way they can stay competitive (on the international level).

But if we continue to duplicate mushroom SMEs who are competing internally, there’s nothing that can be done. We need to ensure we create the large-scale businesses that SMEs will now render support services to. SMEs thrive in trade facilitation, finance consulting, and others. Without manufacturing, they go into trading and importing which is exactly the issue. We need to change our orientation and edge towards industrialisation and medium/large-scale businesses either by amalgamation or by creating a consortium of companies that will develop an industrial pack.

Nigeria’s challenges include unemployment and poverty. What policy-related magic wand can we wave to address our economic woes?

FG’s intervention schemes for industries and entrepreneurs pluck the low-hanging fruits, focusing on what it can do to quickly show it empowered many. That’s not the way a country develops. We need to fund startups, innovation, and value creation not value addition. FG needs to spend money on people coming with new productions. Funding fintech firms and those building apps has contributed more to our challenges. Bank of Industry claims they will finance working capital, not fixed capital and machinery. How many families can raise N100 million to start these? Our unemployment can only be addressed by creating an industrial sector domestically and establishing companies that can massively employ people. With the current effort, FG is only supporting existing businesses, not new ones.

FG needs to change the focus by encouraging research and development. Ask entrepreneurs to develop smartphones for Nigeria that have basic features like those of Infinix and Tecno? Imagine the number of people that buy phones in Nigeria. FG can give them support by mandating that anyone who wants to import phones must purchase 60% locally and import only 40%. Imagine the number of people that will be employed, solving the balance of payment (BOP) problems we face depending on China. We need to invest in producing those basic needs Nigerians have. It’s no magic. No country develops by trading other people’s goods. We need to join the global value chain. We can have companies establish assembly plants in Nigeria. It becomes cheaper, creates jobs, and eliminates engagement with the exchange rate. The government needs to provide the funding and allow the private sector to bring their expertise so that we sell at a lower price that is very competitive. Honestly, any other approach won’t get Nigeria far.

How would you respond to the CBNs ban on FX sales to BDCs based on the allegation that operators seek to dollarise the economy and encourage illegal financial flows?

I don’t see the BDCs as the problem. Who owns the BDCs? None of them operate without insiders supporting them. Nigeria’s system is extremely too open than the way we perceive ourselves to be. It’s easy to buy forex anywhere we want in Nigeria now. I don’t need to go to BDCs to get foreign currency. I can use my local card to buy goods anywhere in the world, all of which puts pressure on our exchange rate since my naira will be converted based on global demand from Nigeria for foreign goods. How does the BDC come in? Even when the BDCs are removed, does that remove the internet and apps I use to buy? Does that remove Flutterwave, Send Wave, and app-based western money transfers? There’s no other solution that can solve our exchange rate problem if we don’t localise demand.

Nigeria is in a debt crisis. What is the lasting solution?

I pity the current government. They don’t have alternatives to borrowing due to the nature of our macroeconomy. Until recently, our main source of revenue, oil, was in a mess in terms of international demand and the price was extremely low. During that period, they tried to stabilise the economy and raise money where they could. If the price is high today, they get to pay back. The aspirations of the current government to build infrastructure as promised is also pushing them to borrow, not minding the cost. If we can do that at a relatively good price, that infrastructure will pay back with time. It’s not a crime to borrow as long as the monies are invested in productive systems that can regenerate income. Unless we tackle institutional challenges, our debt will be a burden in the future. The problem is not the debt but our system for managing the proceeds from the debt that we incurred and our ability to pay it back.

FG needs to look for alternative ways to finance projects. We can’t continue to borrow. There’s a limit, which is how much we earn. By the time debt servicing is taking over 70% of revenue, we can easily calculate that, in the next five to six years, it can take over all the money. But if we borrowed to fund 60% of our budget two years ago and the projects are contributing to the economy at 40%, we know that this will rise to 120% in two or three years. We will have paid back and earned some returns. But when we use divert monies to finance irrelevant consumptions that don’t add value, we will have to pay back the debt, the interest, and the penalty. Debt productivity is what matters.

What loopholes do we need to fix to ensure high-priority projects benefit the people?

There is serious wastage in contract valuation and project execution. If we ensure people deliver what they promised when getting a government contract, monies will be saved. I engage in procurement consulting and I know what I’m saying. We should avoid white elephant projects where governors award needless contracts like building flyovers in places they are not needed. In most cases, what people need is mass transit, not flyovers. If we have security, do we need airports so much in Nigeria? No. We need to change our orientation about what we actually need and prioritise.

How about fiscal policy? Would you say the FG is fully exploring the potentials of tax revenue?

Nigeria is relatively overtaxed in terms of what we pay. But in terms of tax revenue, we’re under-generating. Those earning higher are not paying tax but tax is being enforced on those earning less. From studies, over 40 percent of properties in major urban cities in Nigeria are not occupied because people buy and keep them to hedge against future circumstances. Imagine if all those who own houses in VGC pay appropriate tax rates; VGC tax earnings alone can finance Lagos state budget. The same applies to other upscale cities in Nigeria. Properties alone are a huge source of tax. Secondly, people who earn big income whether in the private sector or government engage in practices that undermine FG’s tax revenue. We don’t need to increase the tax rate but collection and management.

Look at the budget of FIRS and see how much they use on collection. The cost of collecting tax should be extremely small that it does not have a significant impact on revenue generated. But when you’re spending over 30 percent of tax revenue on its collection, then it’s not productive. That’s part of areas where we need reforms. How do we ensure seamless tax collection without incurring so much cost? We all have bank accounts and earn income; it should be automatic. These are the loopholes. FG needs to reexamine itself and figure out how to make the rich pay more than the poor. That’s progressive taxation. In Nigeria, what we have on paper is progressive but regressive in practice.

We’ve seen states like Rivers suing the FIRS over VAT collection. Is Nigeria really ready to go in this direction in terms of tax administration and fiscal autonomy?

From fiscal federalism and the constitution we operate, the federal government cannot collect tax from people they don’t render services to. Tax and service should be merged. FG, states, and LGAs need to define fiscal responsibility in terms of revenue collection and service provision and merge what each tier of government collects to the service it provides. If you don’t provide security, health, education, and water which are social services upon which you collect tax and I have to fend for myself, on what basis are you collecting tax from me? If the state funds the industrial packs, what is FG providing to collect tax from goods produced in those areas? The problem is in the way Nigeria was configured. Who is providing the services for which that tax is to be used? If it’s the state, then states should do the collection. If it is jointly provided with FG, let’s decide the proportions and let that form the basis of tax collection. We should look at it, not from a legal, but in terms of economic responsibilities. That way, there’ll be less rancor.

So much emphasis has been laid on human capital development in Nigeria and how we can leverage our population advantage to facilitate economic growth. How do we navigate from where we are?

We just need to ensure our education equips citizens to be able to identify problems in the system for which there can be a solution. Our education should be oriented towards capacity building and technical/technological training, shifting our focus from language education. We tend to judge people by their oratory skills rather than talent. As long as you can construct roads for instance and get the job done, language shouldn’t matter. Our population is enough market. We have cheap labour like China. They have a large domestic market like we do. If we ask industries to come to Nigeria, produce for cheap, and sell same goods we import in Nigeria, it’s a good starting point. We need to ensure Nigerians have the right skills and entrepreneurial spirit so that you’re creative and innovative wherever you work.

It’s not rocket science. Today, we have universities of technology moving from specialisation to general courses, as against what they were created for because no one is giving them attention. China hardly has any general university. You have universities of construction, trade, communication, law and political science separately. You have a bank of agric, commerce bank, construction bank. They identify sectors and tie education to them. After graduating, there’s a bank to give you a loan to develop your skills. That’s human capital development and financial support. If we have such a system, the crime rate will fall. We need to reorient our education towards industry-inclined technologies.

Add a comment