Eyong holding a barite stone

BY EKPALI SAINT

After working seven hours on his cassava farm during the dry season in February 2018, Nathaniel Ogina approached the stream that runs through his farm in Iyamitet, a community in Nigeria’s Cross River state. The change in the water’s colour startled him as he crouched at the streambank.

“I noticed the strange colour of the water. It was orange instead of the clean water we were used to,” the 30-year-old recounted.

But thirst overcame his hesitation. He drank the water despite its odd appearance, only to be disappointed by an unusual taste and the sudden onset of stomach pain.

Advertisement

“The taste was different, and I started feeling a kind of stomach pain I had never experienced before,” he recalled, his gaze cast downward.

Alarmed, Ogina rushed to his local chief’s house to report his experience. Although aware of abandoned barite mining sites near his farm, he was shocked to learn from the chief — who had attended a seminar on the effects of mining — that the stream could have been contaminated by leachates from waste indiscriminately dumped by barite miners.

Later that day, Ogina took some medication, which relieved his condition. However, days later, his two brothers experienced similar pains, compelling them to take medication as well. These incidents prompted Ogina to stop his mother and six siblings from drinking water from the contaminated stream.

Advertisement

But his worry lingered.

“That experience in 2018 upset me because the stream wasn’t like that before,” Ogina lamented. “I am unhappy that barite mining activities have affected our water.”

Ogina’s experience is not unique to him and his family.

Two hours’ drive from Iyamitet, in the Ibogo community, Esther Onete experienced a similar ordeal in March 2024. On her first visit to her mother’s farm with her two children, her eldest son fetched water from a nearby stream and gave it to his younger brother. Shortly afterwards, Onete noticed strange symptoms in her one-year-old.

Advertisement

“I started noticing weakness in my baby,” the 26-year-old mother said. Though they left the farm early, the situation worsened later that night.

“He developed diarrhoea, his temperature rose, and he couldn’t sleep,” Onete explained. She rushed her baby to a nearby hospital the following day, where nurses attributed the symptoms to poisoning from possible contamination of the stream by the adjacent mine site. After three days of treatment, her baby recovered.

This incident became a wake-up call.

“Since then, I haven’t taken them [my children] to the farm. I no longer drink from the stream near the farm because I still breastfeed the baby and don’t want to take any risks,” Onete said.

Advertisement

HIGHLY SIGNIFICANT IN THE OIL AND GAS SECTOR

The oil and gas industry forms the backbone of Nigeria’s economy, relying heavily on barite — a mineral essential for drilling operations. Barite prevents blowouts during drilling, and its extraction is wreaking havoc on Nigeria’s farmlands, streams, and human health. The mineral has been discovered in nine Nigerian states: Adamawa, Benue, Cross River, Ebonyi, Gombe, Nasarawa, Plateau, Taraba, and Zamfara.

Advertisement

Nigeria possesses the fourth-largest barite deposit in the world, with estimated reserves exceeding 22 million tonnes. Despite its critical importance to the oil and gas sector, local production remains insufficient, forcing the Nigerian government to spend $300 million (over N500 billion) annually on barite imports, according to Olamilekan Adegbite, the former minister of mines and steel development.

The Nigerian Oil and Gas Industry Content Development Act of 2010 mandates that stakeholders prioritise local content in their operations. Yet, the country struggles to reduce its dependence on imports. To address this, the government commissioned a barite processing plant in Cross River state in May 2023 to discourage importation and promote local production.

Advertisement

“Barite is one of the minerals that, if properly developed, can save the country significant foreign exchange,” said Stephen Alao, national president of the Association of Miners and Processors of Barite in Nigeria (AMAPOB). He noted that about 50 local barite mining companies and 35 processors are registered with the association. “We have enough deposits in this country to sustain us and export. That’s why we keep appealing to the government for support.”

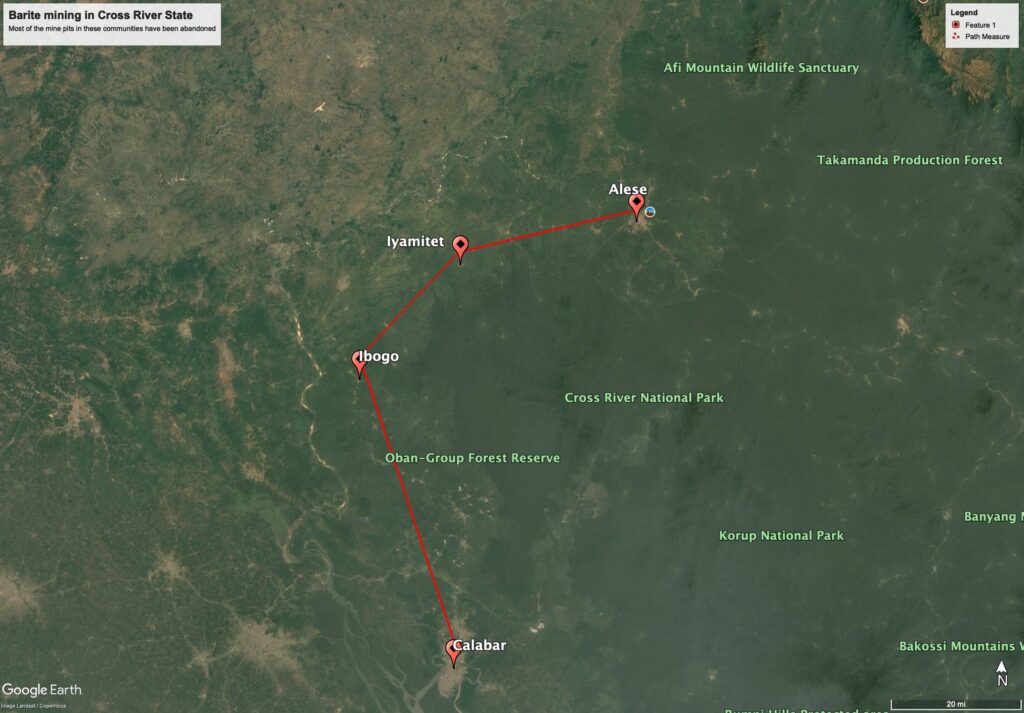

Cross River state, home to Ogina and Onete, is rich in barite deposits, with estimates ranging from 8.6 million to 11 million tonnes. The region has attracted numerous companies that employ open-cast methods to extract the mineral.

Advertisement

“Open-cast mining is a surface technique that extracts minerals from an open pit in the ground,” explained Godswill Eyong, a geologist at the University of Calabar.

Before mining begins, the overburden — earth material covering the barite vein — is removed to expose the deposit. “Overburden refers to the material excavated to access the mineral deposit,” Eyong elaborated.

Ideally, after mining, companies are expected to reclaim the land by refilling the pits with the overburden. However, according to locals, only one of the eight barite mining sites visited across three local government areas in Cross River state had been properly reclaimed. The others were abandoned, leaving open pits and overburden to pose environmental and health risks to nearby farming communities.

“In many cases, overburden contains mining tailings,” said Eyong, explaining that tailings are the materials left after separating valuable minerals from the uneconomic fraction of ore. “Some of these materials contain heavy metals. Rain washes them into streams, which may then be consumed unknowingly by residents.”

The reporter observed that abandoned pits were full of rainwater, creating stagnant pools containing heavy metal residues. Locals in Iyamitet reported that during the dry season, the water in these pits appears to boil, and animals like pythons have been sighted in the vicinity. The deep pits also present physical hazards. Farmers and hunters risk falling into these uncovered sites.

“They should have covered the pits to prevent accidents,” said Theophilus Ngbongha, a resident of Iyamitet. “So far, no one has fallen in, but we pray it doesn’t happen.”

Christopher Adamu, professor of environmental geosciences at the University of Calabar, said these barite mine sites constitute some of the largest barite mines in Nigeria and yet were abandoned without “proper demobilization, remediation, and restoration of the environment,” which is ideal for preventing devastating environmental and health impacts.

INCREASING HEALTH RISK

The rate at which companies abandon barite mining sites in Cross River state has attracted environmental geochemical studies amongst local scientists. In 2015, researchers from the University of Calabar published a study in Science Direct that examined the heavy metal contamination and health risk assessment associated with abandoned barite mines in the state. Findings showed contamination at these mining sites and that the average concentrations of Fe (iron), Hg (mercury), and Pb (lead) in stream water were above the required standard.

To examine the level of water quality in Cross River State, this reporter collected 21 samples from three barite mines in Alese, Ibogo, and Iyamitet communities. The samples consist of seven surface water samples, six surface (0-15cm depth) soil samples, five cassava tubers, and three cassava leaves.

Samples were subjected to standard digestion and geochemical analysis, and the significant parameters analyzed include Ba (barium), Cd (cadmium), Cu (copper), Fe (iron), Hg (mercury), and Pb (lead) for all samples using GBC XplorAA Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer instrument from Akwa Ibom State MST-RD Laboratory.

The water quality results show that the water is acidic with a pH of 5.3-5.7, although the samples were taken during the rainy season in September. The pH of the water samples is below the acceptable range of 6.5 – 8.5, as set by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Nigeria Standard for Water Quality (NSDWQ), which is set by the Standard Organisation of Nigeria (SON).

“The findings reveal that surface water samples were moderately acidic and contaminated with cadmium (Cd), exceeding acceptable levels. This indicates that the water is not of good quality and not good for drinking,” Adamu said, adding that the implication of the result is “[the] potential health risks to inhabitants, including kidney damage, osteoporosis, and cancer.”

Acidic water consumption can cause gastrointestinal issues such as stomach problems. This may be a better explanation for the unusual stomach pain experienced by Ogina and Onete’s son.

‘THERE IS A BIG DIFFERENCE’

Scientists argued that mining typically has the potential to affect soils that locals depend on for farming activities. In 2022, another group of researchers conducted a study to assess the health risks of potentially toxic elements in soils within barite mining areas. Findings showed that most of the samples “present high chronic cancer risks from dermal contact and ingestion for children and adults.”

After analysing soil samples taken from abandoned barite sites, this reporter found that all the heavy metals have concentrations below their respective maximum standard values set by the Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) of Nigeria (Ba 2,000mg/kg, Cd 0.8mg/kg, Cu 36mg/kg, Fe 5000mg/kg and Pb 85mg/kg). Adamu argued that since the samples were taken during the rainy season, frequent rainfall may have washed away substantial amounts of the heavy metals.

“The probable causes of low concentration of heavy metals in soils close to mine sites may be leached away from the soil due to rainfall, irrigation, or groundwater flow [and] presence of minerals that bind or immobilize heavy metals [for example, iron oxides and clay minerals],” he explained.

IMPACT ON AGRICULTURE

Locals like Ogina are beginning to notice a decline in crop yields. He explained that they usually got a bumper harvest when he followed his father to the farm in the 90s. He added that his father had a big yam barn and that they would arrange at least 200 rows in the barn for every harvest. Each row contains the equivalent of 30 bags of yam — counted as one, then across 200 rows. He said things have changed as his number of rows has reduced.

“There is a big difference [now],” he said. “I get 16 or sometimes 12 rows. That is because the yam gets rotten when you harvest it, and for this, it reduces the number of bags I get.”

This contaminated crop is slowly poisoning locals who consume it. A 2021 study by researchers from the University of Calabar, which examined the heavy metals concentration in soils and crop plants within the vicinity of abandoned barite mine sites, found that inhabitants in Iyamitet – Ogina’s community – and the next community in Okurumutet are exposed to heavy metal contamination from the consumption of cassava tubers.

LABORATORY INVESTIGATION

To determine whether exposure to heavy metals impacts people, this reporter selected two human samples – a male and a female from Iyamitet – for radiology and laboratory tests, including full blood count, kidney function test, liver function test, and urinalysis.

The radiology was done at the Nigerian Navy Reference Hospital, Calabar. The results for both human samples showed that their lungs were clear, as there was no growth in their cavity. However, “the only significant finding in their radiography result is that their hearts are enlarged as a result of hypertensive heart disease,” explained Daniel Akpotuzor, a laboratory technician at St. Joseph Specialist Clinic and Cancer Specialist Treatment Centre (SJSCCC) in Calabar, capital of Cross River state. While it is difficult to satisfactorily and clinically argue the cause of this chronic condition as there are different causes, environmental factors such as air pollution, perhaps from barite mining activities, may have contributed.

Alexius Ayami, a 67-year-old father of nine and Iyamitet’s community leader, is one of the samples. The laboratory investigation showed that for his full blood count, only his Packed Cell Volume (PCV) was slightly low and not within the standard range. Also, results from his kidney function test showed that his creatinine is elevated and above the expected standard. Creatinine is a waste product from the digestion of protein in food, and the breakdown of muscle tissue, but healthy kidneys help to remove creatinine from the blood.

“One of the causes of elevated creatinine is heavy metals poisoning,” explained Akpotuzor of the SJSCCC. This reporter carried out the laboratory investigation at this treatment centre.

“The kidney is responsible for filtration function and detoxification. Any toxins that get into the body, the kidney filters it out and attempts to excrete it. So, in the process of handling all of that stress, most times, the kidney can be damaged,” Akpotuzor said. “So this creatinine result is suggestive of the impact of heavy metal poisoning on this individual [Ayami].”

Also, Ayami’s liver function test showed that his alkaline phosphatase – enzymes found in the body – is 121, high and above the standard of (22-92). Akpotuzor explained that heavy metals often settle in vital organs and form kidney, liver, bone marrow, and brain deposits. “This elevated alkaline phosphatase is a possible suggestion of heavy metal toxicity as a result of chronic exposure to toxins that are stressing the body in the process of breaking the toxins,” Akpotuzor explained.

On the other hand, the results of Sarah Okon, the female human sample, showed that both haemoglobin and packed cell volume (PCV) are low. Akpotuzor explained that “she is not very healthy” with her PCV result, which is 32 per cent as against the standard of 40-54 per cent, and that if the PCV drops to 30, she will need a blood transfusion “to be able to cope.”

He added that even her neutrophil, which helps to boost immunity and fight infections, is low as it is currently at 29 per cent against the standard of over 50-70 per cent. Akpotuzor said lymphocytes, which also help to fight infection, are usually on the lower side, but they are on the higher side for Okon.

Akpotuzor also explained that her full blood count is mildly suggestive of bone marrow suppression because there is a suppression in her red blood cell, and white blood cells are not up to normal, meaning the “white cell and red cell have been compromised,” he said.

“[The result] is more typical of what you see in lead poisoning and the inhalation of dust that comes from mining activities and are deposited in the bone marrow. They displace the space that is to be occupied by cells that are to be producing blood, and that is why you have bone marrow suppression,” Akpotuzor explained. “This result is suggestive of bone marrow suppression.”

While her kidney appears normal, laboratory investigation showed a slight elevation in her liver enzymes. “The elevation is suggestive of a damaging process ongoing, so whatever is happening to her is possible it is in an early stage,” Akpotuzor said.

Yet, Okon said she not only eats crops that studies found to contain some heavy metals, “I still drink from the stream, and my [seven] children also drink from the stream.”

On the whole, Akpotuzor said if both Ayami and Okon have continuous exposure to the toxic mining environment, there could be more derailment in their results when they are more advanced in age, given that health complications compound as humans advance in age.

“At this stage, they are asymptomatic. If they are in another environment, the parameters [will] go back to normal. [And] If you keep them there, they will begin to experience the cumulative effect of the exposure that has caused this level of derailment [in their results]. At some point in the future, they will see the consequences of exposing themselves to the [toxic] environment,” Akpotuzor said.

But it appears locals have no other option.

“I am still drinking from the stream. I took drugs the different times I had stomach pain. [But] I think I am used to the water as I no longer take drugs. I believe my system has adapted to it,” 48-year-old Ngbongha, a father of four, said.

‘IT WILL NOT KILL YOU’

Despite researchers’ findings, Alao, the national president of the Association of Miners and Processors of Barite in Nigeria (AMAPOB), insists that the associated minerals, such as lead, are hazardous, not barite itself. He argued that barite mining does not pollute streams, unlike mining minerals such as gold.

“Water pollution does not occur in barite mining [because] we don’t use chemicals to mine barite; we do extraction,” Alao said. “You can even drink barite — it will not kill you. It is a medicinal product [and] can be taken as a formula before undergoing an internal x-ray.”

While Alao is correct that barite is used in medical imaging and other industries, such as cosmetics, paper-making, rubber, plastics, and paints, the applicability of barite in these contexts does not negate the fact that it contains heavy metals.

One of the abandoned barite sites in Alese belongs to Presco Log Nigeria Limited. According to James Egbo, the company’s founder, it was registered in 2014. Although a search of the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) records yielded no matching results, Egbo claimed his company began mining barite at the site one year ago, having obtained community consent for an undisclosed fee. However, Egbo said financial challenges forced the company to pause operations, although the project remains licensed for five years.

“It’s still on,” Egbo explained. “I intend to return to the site to continue mining.”

Egbo also denied that his company’s activities had contaminated local streams, claiming that environmental impacts are carefully considered.

“Whenever we need to drain water, we do so around 9 p.m., ensuring the stream clears before morning,” Egbo said. “We also ensure the drainage is not near any streams.”

WEAK IMPLEMENTATION

According to Alao, barite mining pits often become too deep and dangerous for continued operations, leading companies to abandon them. He noted that in such cases, the Environmental Protection and Rehabilitation Programme (EPRP) mandates companies to reclaim the land by properly refilling pits and planting trees.

“[The companies] are supposed to reclaim the land properly,” Alao said. “But if there are many abandoned sites, it means the federal mines officers are not doing their jobs.”

Archibong Otu, chairman of the Cross River state branch of the Mineral Resources and Environmental Management Committee (MIREMCO), admitted that mining is inherently destructive. He explained that adherence to established environmental standards is essential but often poorly enforced.

“Mining, by its nature, destroys the environment. The law provides measures to mitigate these damages and protect water sources,” Otu said. “But compliance levels have not been good.”

MIREMCO, established under the Nigerian Minerals and Mining Act of 2007, is tasked with supervising mining activities and addressing illegal mining nationwide. It operates as a collaboration between federal, state, and local governments. In Cross River state, MIREMCO draws its membership from state ministries of agriculture, environment, mineral resources, and lands, with the federal mines officer serving as secretary.

However, Otu highlighted that a lack of funding hampers MIREMCO’s efforts. Since the committee’s inauguration in March, it has received no financial support.

“We have not been funded with a single naira,” Otu said. “Despite this, we are working and will continue to do our best to rescue the state from destruction.”

Otu attributed many of the challenges in the sector to poor enforcement of the Minerals and Mining Act and federal control over the extractives industry. He criticised the federal government for failing to decentralise mining regulations, leaving state governments powerless to address the environmental and social impacts of mining.

“The state is closer to the people, but the federal government insists mining is on the exclusive list,” he said. He explained that when Cross River State attempted to regulate mining activities, companies took legal action, citing the Mining Act.

“Some investors have taken the state to court and won judgments based on the blind spots in the Mining Act,” Otu said.

“There is an urgent need to reclaim abandoned mining sites,” he added. “Some pits, abandoned for over 20 years, are so deep that anyone who falls in is unlikely to survive. Reclamation must be funded through a dedicated fund or by holding the federal government accountable for collecting royalties from mining companies.”

“I DON’T WANT TO DIE YOUNG”

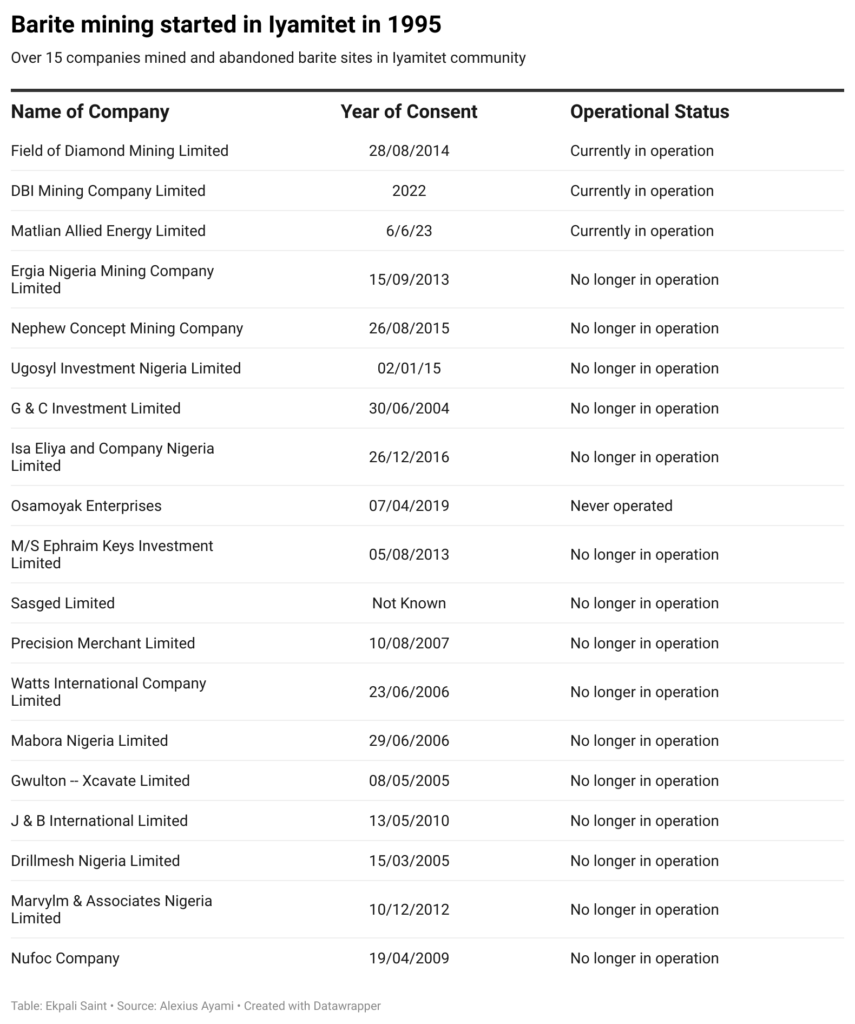

Barite mining in Iyamitet began in 1995 on a small scale. However, according to Alexius Ayami, a 67-year-old community leader, the arrival of companies with excavators in the 2000s intensified operations. The barite was transported by trucks to oil-rich Port Harcourt.

Ayami said the community has no exact record of how many companies have mined in Iyamitet. However, he listed 16 companies that mined and abandoned sites; three are still in operation. A search of CAC records revealed no matches for most of these companies.

Ayami explained that before the community consents to a company, the company pays a fee of N2.5 million, and the community gives a one-year probation, which entails the company prospecting on the site to ascertain the deposit of the mineral. As soon as the company confirms this, the community invites the company and hands over a Community Development Agreement (CDA). This document will specify what the company will do for the community, often including awarding scholarships to community members and building roads and medical treatment centres.

But rather than provide all this, most of these companies left a legacy of pollution, contaminating the streams locals depend on for drinking and cooking. This reporter found makeshift security houses near some of the abandoned barite sites, which Ayami said were erected by some of the companies.

“The only way you can know they have polluted the stream is the change in water colour,” Ayami said. “If you drink from it, you might not notice any change. But most of us who know the effect don’t drink. The joy I have is that we have never had a casualty.”

Meanwhile, these companies employed some of the locals to mine barite. In the Alese community, for example, Oscar Asari said that Omar International Limited first came to the community in 1998 and entered into an agreement with the community. Like Iyamitet, Asari said the company paid the Alese community consent fee. Once that was completed, he said the company brought in workers and employed community workers.

Asari was one of the miners. Then, these miners did the extraction, and each miner had his pit where he extracted the mineral. With chisel, digger, and hammer, Asari said each miner could dig and extract five tonnes, and a tonne was N1,000 in the 90s but now N10,000, which the company pays. Asari said that the company brought in its truck, loaded it with about 30 tonnes, and headed to Port Harcourt.

In addition to the physical injury barite can cause as the stone is sharp, Asari said they have also noticed the quality of the water they fetch from the stream has reduced.

“Now, water is flowing well, so you will not notice,” Asari told this reporter in September, just after the heavy rain that fell for about 40 minutes stopped. “[But] any barite site where its water flows into the stream, the water is usually different. I have noticed it. If you drink the water, it will seem like they put alum, and one could get skin rashes,” Asari said.

One day in 2001, for example, Asari said one of his son’s friends bathed with the water from one of the abandoned mine pits and started experiencing skin rashes. “I know the thing is poisonous. [That is why] I usually beat children not to go close to that place,” he said, pointing to an abandoned barite mine pit.

Asari said that three companies have mined and abandoned Alese, where Egbo’s company has a mine pit.

This reporter could not assess the depth of the abandoned barite mine pits because it was the rainy season, and they were filled with water.

Back in Iyamitet, Ogina has stopped taking water from the stream near his farmland. So, while going to the farm, he fetches water from another stream not connected to the mining sites. But he hopes the federal government will regulate mining activity so that locals’ lives won’t be at risk.

“I don’t want to die young,” Ogina said, leaning forward to make his point. “I plead with the government to do something urgently.”

This story was produced with support from the Tiger Eye Foundation under the On Nigeria programme, funded by the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment