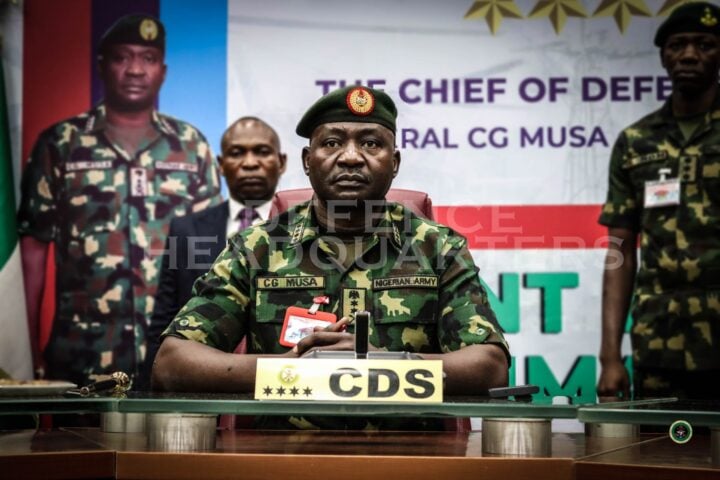

Entrance of the Zoo Estate, Enugu, south-east Nigeria

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center Rainforest Reporting Grant.

As a child growing up in Warri, Delta state, Ambrose Igboke was regaled with folktales of tortoise mischief, wisdom, and longevity. The lion was always touted as the king of the forest. So, whenever he travelled with his uncle to his village in Enugu, Nigeria’s south-east zone, they would stop at the massive zoological garden in the state to see the tortoise and other animals.

Other children and adults would swarm into the zoo to have fun and catch a glimpse of the animals. From the lions, monkeys, leopards, ostriches, and gorillas to the reptiles, the animals were in clear view, and they provided entertainment to the teeming visitors as the zookeepers answered a series of questions about the creatures.

“Those were the good old days,” 48-year-old Igboke recalled with an enchanting smile.

Advertisement

“We don’t see wild animals except in books and on television. The only opportunity we had then to see those animals was to visit the zoo. There was no zoo in Warri; the closest we had then was Benin, and it was not on our way home. So, we used every opportunity to come home to visit the Enugu Zoo.”

When Polycarp Chiwetalu, a resident of Enugu, visited the zoo as a child, the animal that fascinated him the most was the baby gorilla named Sunday. After each visit, he longed to go back to see Sunday. At the time, most of the animals were emaciated and could hardly walk, their eyes roving around for food from visitors. Then, some of the animals started dying.

“It was fun watching the animals. I watched the lion play inside the cage and the gorilla playing with its children. We did not pay to visit the zoo because the managers loved to see visitors come in to spend time and enjoy themselves. But people freely donated to feed the animals because they were not adequately fed,” Chiwetalu said.

Advertisement

Chiwetalu didn’t visit the zoo again for a long time, and Igboke’s last visit was in 1992. Years later, when Igboke returned to the state as an adult and told his relatives that he wanted to visit the zoo to relive old times, he received sad news: Most of the animals were gone, and the state government had closed the zoo.

“It was sad. I miss the old zoo. We are unfair to this young generation, depriving them of everything nature offers us. Now, we lock them up to watch movies at home. They only have their gadgets. Many have grown to be adults without seeing a live wild animal,” Igboke said.

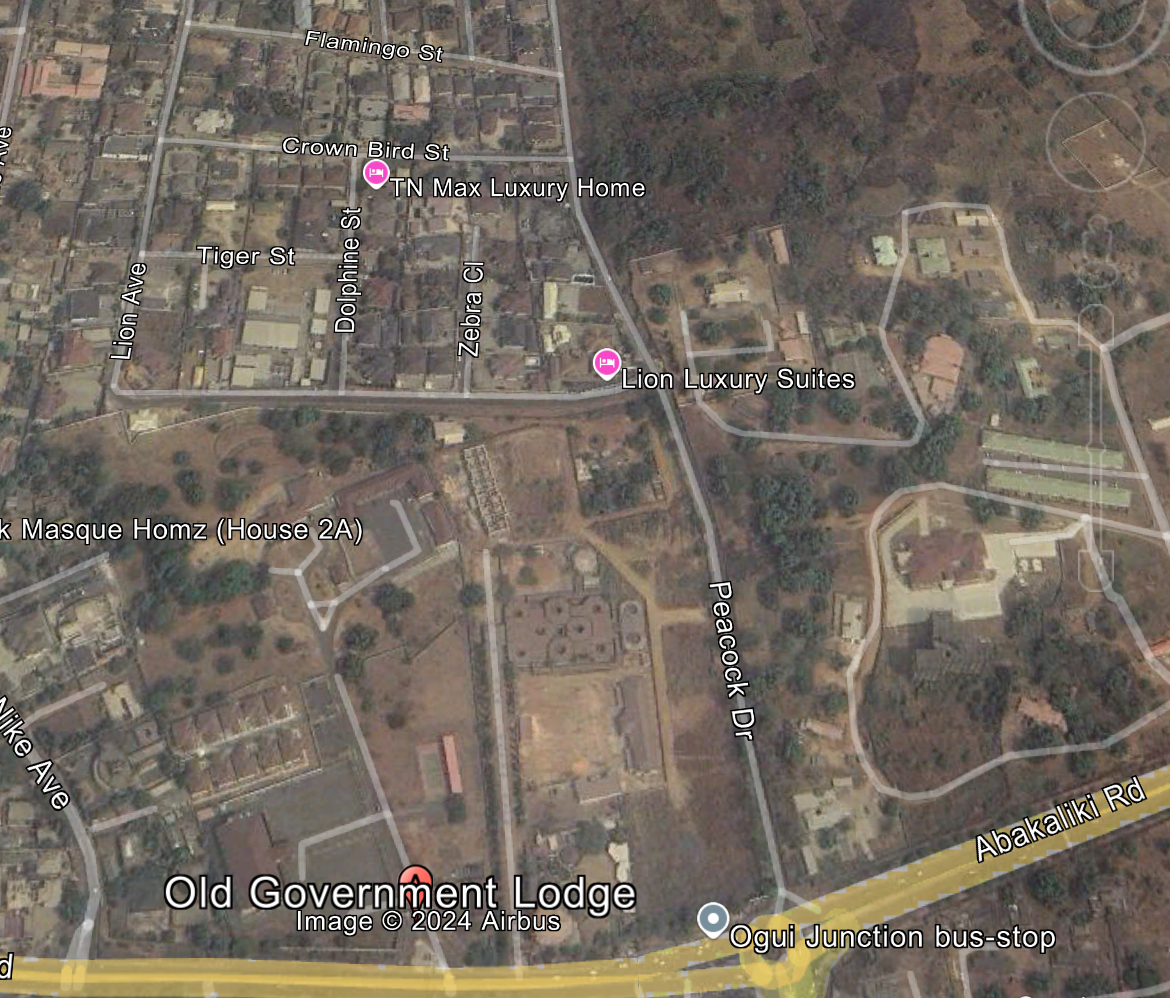

Located in the heart of the coal city, as Enugu state is fondly called, the zoological garden was 1.72 miles away from the government house and right behind the old governor’s lodge. It used to be one of the green areas in the state capital. But it was a fast-developing bourgeois settlement, and the zoo sat in that prime location. It also shares a fence with the 82 Division of the Nigeria Army barracks and is surrounded by posh residential estates. Hence, all eyes were on the massive land with rich rainforests.

Following the zoo’s closure, a former worker who demanded anonymity told TheCable that the animals were relocated to Nsukka, a university town, the forests were cleared, and the land was transformed into an upscale estate.

Advertisement

“Then, the government began to allocate the land to some of its top officials and wealthy people in the state. They were the ones who could afford the cost of the land. It’s within the Government Reserved Area (GRA). Initially, it was called Zoo Estate. But it was later renamed Ekulu East Estate so that it would no longer be associated with the former zoo,” the official said.

Investigations showed that Peter Mbah, the state governor, has a property in the alluring estate. Mbah was chief of staff and later commissioner for finance under Chimaroke Nnamani, a former governor of the state. During Nnamani’s administration, the zoo was shut down and transformed into a utopia for the elites.

“Is there anything wrong with owning a property in the estate?” Dan Nwomeh, senior special assistant on media to the governor, asked in a chat.

“The former zoo was converted into an estate and allocated in the first tenure of the administration while he served in the second tenure.”

Advertisement

Calls and messages sent to a phone number associated with Nnamani were not delivered. This reporter asked the reason behind the facility closure, the beneficiaries of the land allocation, and if he was also a beneficiary. A message was sent to his verified X account, but he has not responded.

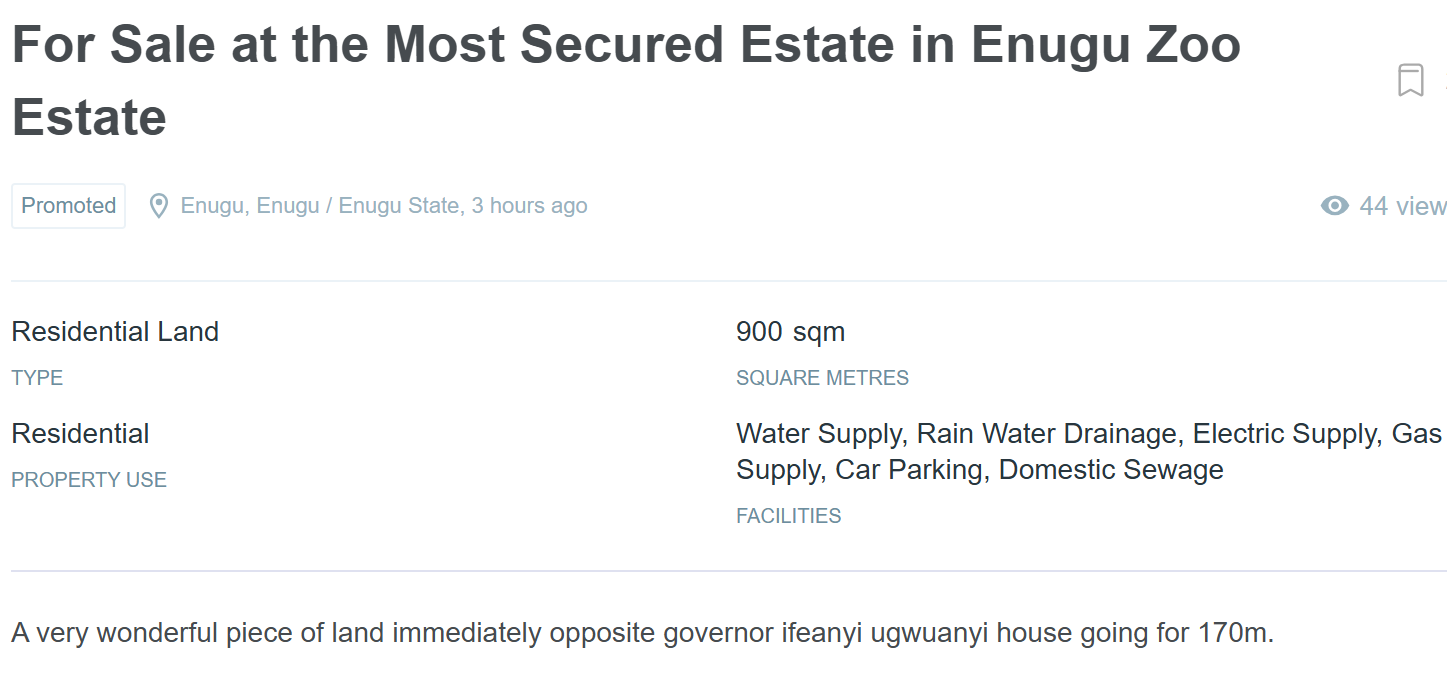

In an old online listing by a realtor, a property close to a building reportedly owned by a former governor of the state, was put at N170 million ($114,000). Another property in the estate was advertised for N250 million ($167,000). One was listed for N2 billion ($1.3 million) in 2021. One thing that stands out in the advertisement of properties in the estate is the phrase, “The most expensive estate in Enugu”. In addition, the estate boasts a police post.

Advertisement

Two signboards at the front of the estate warn visitors to beware of their activities. Stern-looking security officers only let visitors enter the area with proper identification. A tour of the large and quiet estate shows nothing left of the zoo after its conversion about two decades ago. The cages and wildlife sanctuaries have been replaced with luxury homes and hotels.

To immortalise the former occupants of the estate, streets were named after animals whose natural habitats were destroyed to create room for humans to build theirs. From the Ogui roundabout, you can access the estate through Peacock Drive. Then, you move to Lion Avenue, Tiger Street, Eagle Street, Flamingo Street, Leopard Street, Crown Bird Street, Zebra Close, Giraffe Street, Fox Street, Dolphin Street, and Penguin Close.

Advertisement

THE SCRAMBLE FOR THE ‘ONLY SURVIVING’ ZOO

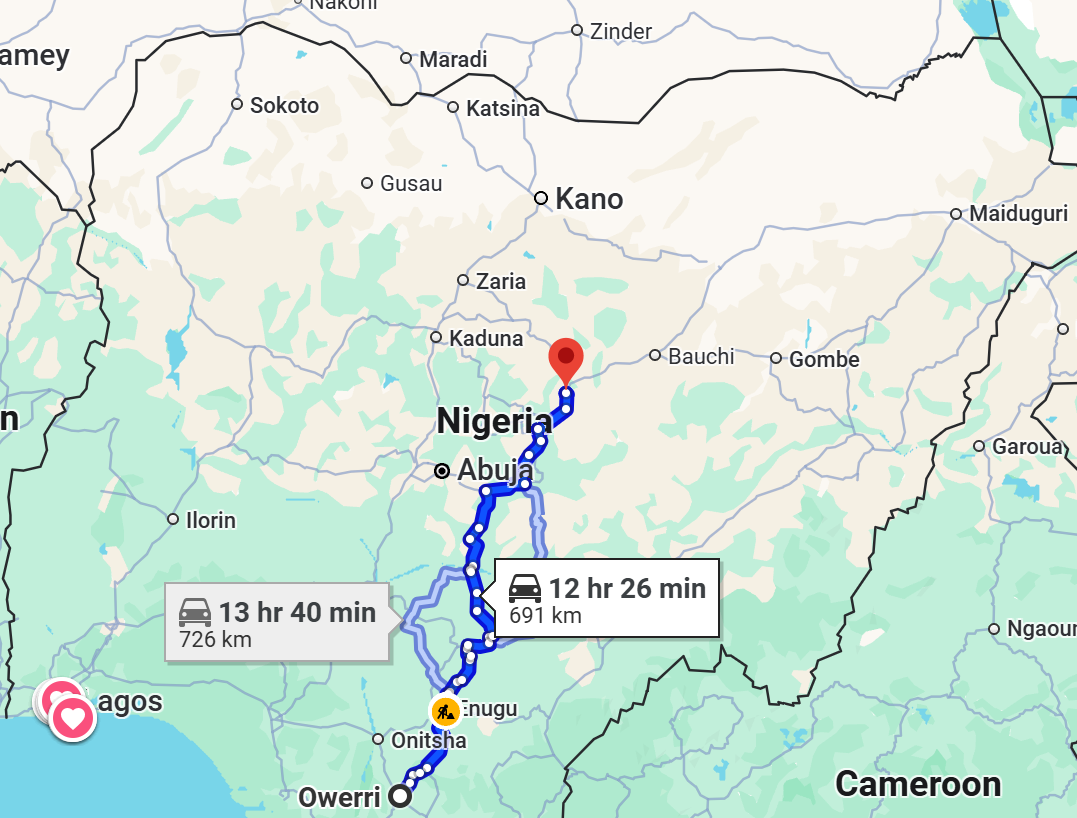

Following the winding up of the Enugu zoo, wildlife lovers in the south-east had no other option than to travel miles to the Imo State Zoological Garden and Wildlife Park, the last surviving zoo in the zone. The park became the primary hub for recreation, education, and research.

Advertisement

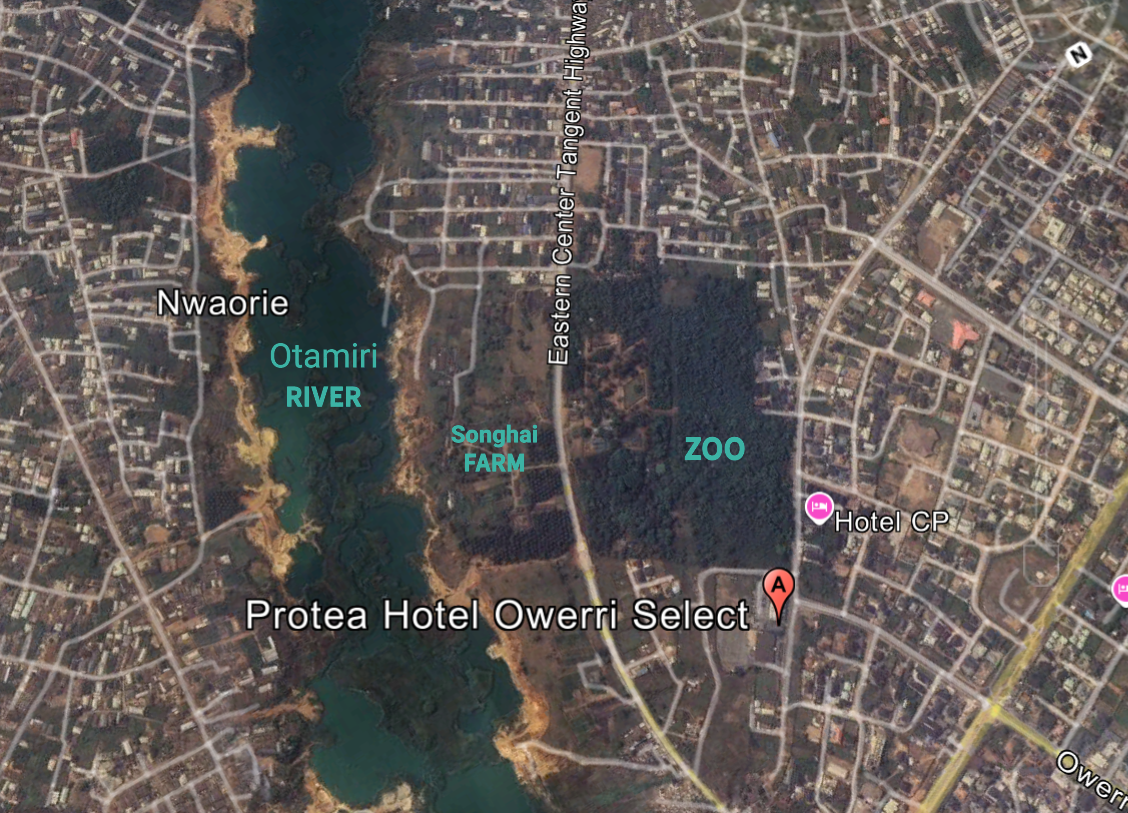

The zoo, founded in 1976, is nestled in a 23-hectare reserved rainforest along the old road leading to the historic Nekede community in Owerri West LGA of Imo state. The gazetted rainforest accommodates different species of animals and over 20,000 species of plants, many of which are endangered.

The state wildlife park and nature reserve has endured many trying times. In 2020, a hyena escaped from the zoo and caused panic in the community. The animal was recaptured. In 2021, deep gully erosion from the nearby Otamiri River damaged the road connecting the zoo to the metropolis.

That same year, over 250 animals were reported to have starved to death in the facility, and appalling pictures of starving animals went viral on the internet. The zoo needed about N1.2 million (about $3,000 then) monthly to cater to about 500 animals. Still, the government subventions were not coming as and when due, and the paltry N1,000 (currently less than a dollar) entrance fee could not sustain the feeding. Successive governments in the state kept promising they would refurbish and fund the park.

During the 2019 World Environmental Day celebration, Emeka Ihedioha, former Imo governor, promised to renovate the facility to international standards. He said his government would prioritise the preservation of the ecosystem. Funds were released, work began, and a new administrative building was built.

Barely a year after becoming governor, Ihedioha was removed from office by the supreme court in 2020. Hope Uzodinma was declared the authentic winner of the 2019 gubernatorial election that brought in the former.

During the 2020 World Wildlife Day, the new governor also vowed to reform the zoo to international standards, retrieve designated forest reserves, and form a special wildlife and habitat conservation bureau.

“Through our actions and inactions, the conservation of our national biogenetic pools today has a direct impact on our generation and future generations. Even today, most modern medicines are derived from herbs and roots, and if humanity continues to recklessly abuse our ecosystem, what then is the way forward for the world and Nigeria?” Uzodinma was reported to have asked.

“Today’s celebration fast-tracks the question boldly and loudly to the fore of the inner recess of our consciences, both as individuals and as leaders of our respective nations and organisations, to wit. In our lifetime, have we added value to the preservation of the natural habitat, biodiversity, or wildlife we met on earth, or have we helped to ravage, deplete, or destroy it? My candid take is that we are all guilty of not doing enough to preserve the natural habitat we met.”

Two years later, Uzodinma acted against his own words. On February 21, 2023, some state government officials visited the zoo and evacuated all the animals. The officials had informed the zookeepers that the animals would be relocated to the Jos Wildlife Park in Plateau state – a distance of about 13 hours by road. Bad roads, security checks, occasional rests, and any unforeseen circumstances along the roads could make the trip up to 20 hours or more. Zookeepers told this reporter that some animals died during the translocation.

In July 2023, the state officials returned to the zoo with heavily-armed police officers to destroy the structures in the zoo. Bulldozers rammed into the forests and levelled the trees.

When this reporter visited the zoo opposite the Songai farm on November 7, the only indication that the place was once a former wildlife and nature park was the new administrative building that still adorns the zoo signage. A new fence was constructed to lock out the facility from outsiders. There was no visible entry point.

“There is ongoing construction inside the zoo, and you cannot enter. The facility is under close watch by guards,” Kingsley Okoye, a community resident, told this reporter while trying to find an entry route from the nearby Madoka bus stop and forestry building of the ministry of agriculture. Okoye said locals cannot enter the facility because there is a conflict between the community and the government over ownership of the expansive land.

The community had heard the government wanted to convert the zoo into a housing estate. Okoye said a piece of land around the area is valued at N100 million ($67,000) and above. The community dragged the government to court over the alleged forceful takeover of their ancestral land. The community leaders claimed the land was leased to the defunct eastern region government for agricultural purposes and must be returned if the plan changes.

In 2023, the federal high court ruled, restraining the government from taking over the land. The court of appeals upheld the high court’s ruling, and the government took the case to the supreme court.

Under the Umuejechi Central Assembly, community indigenes had warned individuals and investors who intended to buy the land to avoid such “calculated risk.”

“All the lands comprised in the former Agriculture Development Corporation (ADC), which includes the moribund Nekede Zoo and the adjoining lands that the Government of Imo State is presently trespassing into, are the bona fide property of the people of Umuejechi Nekede,” the community said in a statement.

“The land was leased to the government of the defunct eastern Nigeria in 1956 for a period of 99 years. The lease, which still has 36 years to expire, was registered as No.16 on page 16 in volume 45 in the lands registry in the office at Enugu, now kept in Owerri.

“The government of Imo state does not have the right to convert the lands into residential plots and allocate the same to individuals or groups. It is even more illegal when the new allocations are for 99 years, much more than the remaining years the said lease has to run.”

But the indigenes didn’t stop there. They’ve consistently protested, asking the government to respect the court’s decision and observe the status quo until the supreme court decides on the land. In July, the community members protested a purported plan to sell the land to an international hospitality company.

DISREGARD FOR BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION

“I was properly informed about the plan to shut down the zoo. Initially, they didn’t come out clearly. You know the way some of these politicians behave. They came under the pretension that they wanted to relocate the zoo, and I argued with the governor why he shouldn’t do that. He asked why, saying the zoo is in the centre of the city where the land is very expensive,” Francis Abioye, the general manager and principal conservative officer of Imo Zoo and Wildlife Park, said in a phone interview.

“He (governor) said the zoo would be relocated. I asked him about the trees. The beauty of the zoo is that old, natural virgin forest. For the next 100 years, you can’t generate them elsewhere. When I understood how dangerous it was for me to continue to resist, I gave them a better option. I said it’s either the government takes me down or provides another land not too far from the city before they can destroy that place. But they were not interested in the option I gave them.”

Abioye alleged that the governor attempted to bribe him so the government could have its way with the facility. He said his resistance led to the abduction of his wife and an attempted assassination on his life. Abioye eventually fled the country following the release of his wife from captivity.

However, he is still traumatised by the tragic event and the poor condition of the zoo staff, who were rendered jobless despite being owed a backlog of salaries. Abioye said that despite the government’s neglect, the zoo welcomed about 100,000 visitors and generated about N11 million annually ($7,300), but it can generate up to N400 million ($267,000) if adequately maintained.

Aside from the financial potential, he noted that the land was a sensitive ecosystem acting as a carbon sink and watershed, shielding the area from gully erosion, which often threatens it.

”That is why you see that the only green area in the city capital in Imo was the zoo. The forest served as an oxygen bank for the city. It was also a local conservation heritage site where endangered and protected species were preserved for posterity. We have a laboratory of over 20,000 species of plants, most of which are of diverse medical value. All of them are gone,” Abioye said.

“Crime has been committed against animals and plants protected by law. The destruction is permanent damage. There is a systemic threat to conservation generally in Nigeria, especially in the zoos, because everything comes to the table of politicians. Politicians have become a threat to virtually every fabric of our nation’s system.

Calls and messages sent to Declan Emelumba, Imo commissioner for information, seeking reactions to the controversy around the zoo closure weren’t answered.

Speaking on the development, Orimaye Jacob Oluwafemi, national secretary of the Wildlife Society of Nigeria (WiSON), said land grabbing, poor funding, and the illegal wildlife trade had worsened the challenges faced by most zoological gardens.

“Evidence suggests that inadequate government support has contributed to the decline of zoos in Nigeria, effectively hastening their potential extinction. Without sustainable conservation methods, Nigeria risks losing ecotourism prospects, depriving local people and the national economy of important cash,” Oluwafemi said.

Tunde Morakinyo, executive director of the Africa Nature Investors (ANI) Foundation, has a contrary opinion. He said zoos should not exist and should be allowed to go extinct. However, he condemned the destruction of the forests surrounding zoos.

“Animals belong in the wild and not in cages. This is why I think most zoos should be closed down — including in Nigeria, where we cannot even feed the animals,” he told TheCable.

Morakinyo noted that Nigeria needs to redesign conservation projects to become development engines in their locations.

KILLING THE ENVIRONMENT TO CURE HOUSING DEFICIT

Nigeria, a country with reserved sanctuaries for rich flora and fauna, still struggles with conservation issues. With rapid urban development and an escalating population, state governments are selling conservation centres and converting them into upscale residences. Aside from the Enugu and Imo zoos, other wildlife and nature parks across the country are battling existential crises.

In 2023, some environmentalists in Ibadan, the capital of Oyo state, protested the state government’s plan to sell the forested part of the 58-hectare Agodi Garden and turn it into a residential estate. The facility between Mokola Hill and the state secretariat was created in 1967 as a conservation forest and recreation area. Then, it was called the Agodi Botanical and Zoological Garden — until the animals gradually disappeared.

The landscape has a wetland, and the forest reserve surrounding the garden serves as a watershed for the ravaging Ogunpa River, which destroyed the facility with flooding in 1980. The incident was said to have killed most of the animals and also claimed some lives.

However, Williams Akin-Funmilayo, the state commissioner for lands, housing, and urban development, said the government’s proposed Baywood Estate would not encroach on the gardens.

“The reason why the government is intending to convert the forest to a housing estate is to make the place more secure, as the place is a death zone that serves as a harbour to many criminals where many innocent lives have been lost,” the commissioner had said.

Akin-Funmilayo told TheCable that the government conducted an environmental impact assessment (EIA) before the project began on the Ogunpa Dam Forest reserve, and the outcome was “favourable”. However, he failed to provide further details on the content of the EIA.

The controversy has morphed into a legal battle. Adeniyi Uthman, a lawyer in the state, sued the state government over the planned conversion, saying it is “repugnant to natural justice and a flagrant abuse of power”. The Bodija Estate Residents Association has also sued the government over the destruction of the forest.

Like food and clothing, shelter is one of humans’ three basic needs. The Nigerian government estimated the country’s housing deficit to be 28 million units in 2023, adding that N21 trillion ($140 billion) in funding is needed to solve the housing shortage for its over 220 million population.

Experts who spoke with TheCable said the destruction of natural resources and transforming them into a paradise for the rich will not solve Nigeria’s housing deficit but attract dire implications for the environment and the country’s conservation tourism.

“The Agodi Gardens and forest is a big catchment area. They cut down over 5,000 trees in that place, and they have not stopped. There is a tremendous risk of flood because of what has been done. It’s an environmental emergency. Most of those trees are about 70 to 80 years old,” Rosalie Ann Modder-Oyefeso, co-founder of Save Our Green Spaces Group, told TheCable.

“The destruction of these forests won’t solve Nigeria’s housing deficit. It’s a luxury estate. It’s for a few people with money. The people who don’t have houses are at the bottom of the economic ladder. They are not doing the housing projects for the ordinary citizens.

“In Ibadan, they came up with stories that men of the underworld hid in the forest. You can’t cut down the forest because of that. You hire forest rangers. You can’t cut your nose because it has a boil. I foresee a future disaster if something is not done now.”

Edem Eniang, a professor of wildlife resources management, condemned the conversion of conservation sites to residential quarters for the rich and the political class. He said this trend calls for urgent implementation of the environmental impact assessment provisions, including baseline and post-impact assessment studies, for a better future for all.

The National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) did not respond to a request for comment on its efforts to protect these forest reserves and conservation centres from state government encroachment.

As though resigning to fate, Modder-Oyefeso concluded: “The government deserves an award for absurdity.”

Add a comment