The National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) was established in 2005 to enable every Nigerian, no matter socio-economic status, walk into a hospital and get treated with little or no money in their pockets. Fourteen years later, the scheme has failed to provide this access, especially in medical emergencies. TheCable finds out why.

As Destiny Aigbe walks into the block where National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) services are rendered at the University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), the first thing the 17-year-old sees is a bold signboard announcing that “the enrollee is king”. Incidentally, on that sweltering afternoon, he has just consulted with the doctor who diagnosed him with a chronic fungal disease that has formed a permanent rash on his skin.

He is asked to do a liver function test (LFT) to ascertain the capability of his liver to process the drugs about to be prescribed. But on getting to the laboratory, he is turned back because his health maintenance organization (HMO) — the intermediary between NHIS and hospitals — has not paid for his health insurance for that month. Confused, he goes from room to room to verify his status as an enrolee on the scheme but is still denied the test.

Aigbe, a student, is forced to return home to ask his father for N2000 to do the test as well as cover other expenses pertaining to treatment. Going by NHIS guidelines, he is not supposed to pay because he is an enrollee. The scheme is a social security system that guarantees the provision of healthcare. A certain amount of money, called capitation, is deducted from his father’s salary every month for medical purposes, with or without seeking treatment. The federal government pays 3.5 percent of a federal civil servant’s basic salary to NHIS, while 1.75 percent is deducted the employee’s contribution to the pool.

Advertisement

These contributions create a pool of funds paid as capitation to HMOs for onward payment to the hospitals. The HMOs are like insurance companies, who in like manner, pay the capitation to accredited healthcare providers, such as hospitals and clinic, on behalf of the enrollees. Akin to the classic social insurance model, this pool of funds is intended to reduce the burden of paying out-of-pocket which has been proven to increase poverty. Furthermore, enrollees have access to free doctor’s consultation, laboratory tests, a subsidy on drugs (they contribute 10 percent to the cost of all drugs) and equally a certain amount of discount on bed space, if on admission.

Frustrated by the refusal, Aigbe stomps through the length and breadth of the waiting area, soliloquising: “They said I should call my HMO. They said that I cannot do this test for free. That is how they behave here.” TheCable approaches him for comments and he fumes: “The way these HMOs are treating us is not fair. After they will say enrollee is king!”

Yusuf Usman, the former NHIS executive secretary and bone marrow transplantation, once accused hospitals of treating enrollees as “lepers” because HMOs withhold their capitation.

Advertisement

‘NO FAITH IN NHIS’

Aigbe’s experience immediately opens the floor for other enrollees at the hospital to voice their frustrations. Charity Jimoh, a federal civil servant and mother of three, tells TheCable that though she has been using the service for the past eight years, she does not totally have faith in it, especially in the time of emergency.

“NHIS is not worth it. One day I brought my children. After we waited all day, I bought eggroll and Gala to pacify them, at last, we saw the doctor, and he said, there are no drugs. What is the purpose? After that day, I went to register at a private hospital as back-up,” she says. “There were also two occasions when I got to my hospital and they said my HMO (Premier Medicaid) hadn’t paid, so I couldn’t receive treatment. So I had to go to another hospital where I had to pay. Even today now, I brought this my child (her little girl of about four sitting on her laps), I was asked to pay 10 percent of the drugs they wrote for me, out of that 10 percent, I already paid N700 extra. I don’t even understand what that one (the extra N700) is for.”

Mabel Osahi, another embittered civil servant at the hospital, is furious because she has to pay an additional N2500, apart from the mandatory 10 percent of the cost of drugs.

“I am a member of staff of this hospital, but I am very angry with this NHIS. I brought my mother here today and they told me to pay 10 percent and to also add N2500 for drugs. What is that for? These NHIS are not trying at all,” she retorts.

Advertisement

Joy Omo, a housewife, also shares her experience.

“I have three boys. One day all of them fell sick at the same time. They had measles, and so they couldn’t go to school. So I rushed them to UBTH, but was refused treatment because they said my HMO had not paid for that month. I called my husband and we took them to a private hospital for treatment where we had to pay,” she narrates.

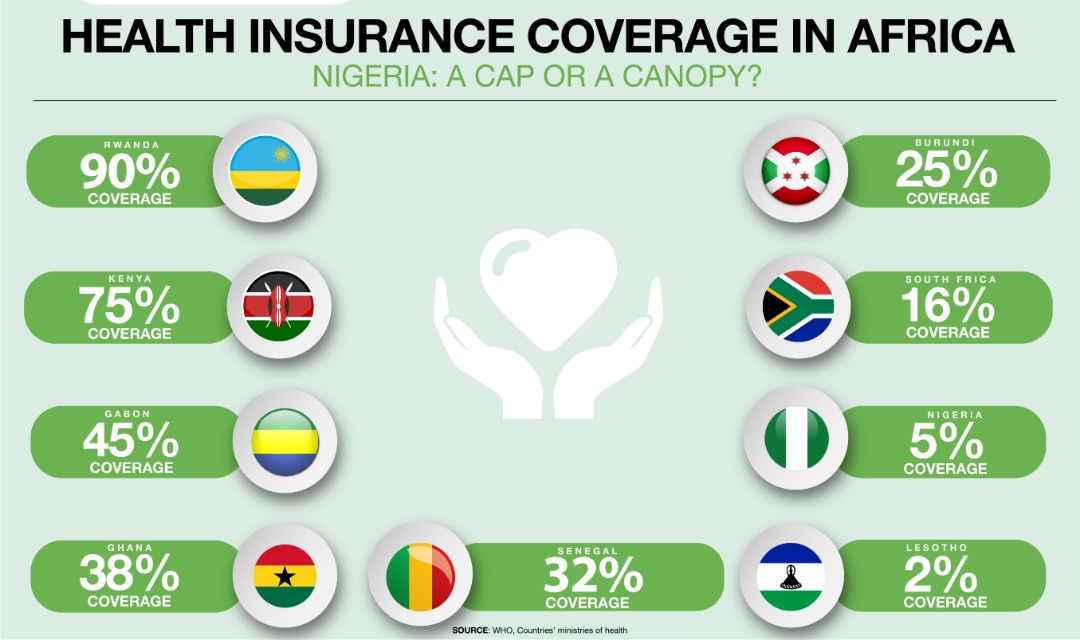

After 14 years of covering only 5.1 percent of the country’s 180 million people — that is 5-6 million federal civil servants and their families and a few private-sector employees, according to 2018 Health Maintenance Organisations (HMOs) Industry Report by Agusto & Company — those that are insured cannot vouch that NHIS can bail them out in medical emergencies.

EMPTY DRUG STORE

TheCable gathered that in cases where HMOs have paid monthly capitation, drugs are often not available to accompany the treatment. According to the scheme’s guidelines, enrollees contribute 10 percent to the cost of drugs, but in many cases, they bear the total cost. Testifying to this is the medical doctor on-call duty at the clinic of the Nigeria Institute for Oil Palm Research (NIFOR), Edo state.

Advertisement

“As I am speaking to you now, we have not received a drug supply for the past six months. Our drugs store is empty and when we write to the institute, they tell us that the contractor that is supposed to supply the drugs have not done so. How can you run a hospital without drugs?” asks the doctor who wishes not to be named.

This centre is one of the NHIS-accredited healthcare providers which serves a population of 20,000 and has at least 1000 enrolees.

Advertisement

“Most of our NHIS enrollees are leaving. They said we don’t give them drugs. When a patient comes into the hospital for treatment, consultation, etc. The highpoint of treating a patient is to give them drugs, but when we don’t give them drugs, they will not come next time. But if we give them drugs, they will go about telling other people that ‘they give drugs in that hospital’, which will lead to more enrolment. Giving them drugs is the way a patient knows that you are a good hospital,” he adds.

Commenting on drugs availability, Jimmy Adeyeye, the medical director of Ibijola Hospital, Agbara, Lagos, (NHIS-accredited), says drug availability and affordability is a major problem hampering the efficiency of the scheme. According to him, the reason for drug stock-out in most hospitals is the high cost of medications and the refusal of NHIS to review what it pays so as to match the market trend.

Advertisement

“It is the same rate they started with 14 years ago that they are still using,” Adeyeye, who is also the national chairman of the Healthcare Providers Association of Nigeria, says. Apparently speaking the minds of NHIS-accredited hospitals and clinics, Adeyeye says: “There is a need for the review of the cost of treatment because time has reduced the value of the money. For instance, the initial capitation per enrollee used to be N550, but they increased it to N750. Immediately they changed it to N750, the removal of fuel subsidy took away all that advantage, so we are back to square one again. Also, the cost of a lot of drugs have gone up in the market, but the NHIS is still using the old rate. Within these 14 years, look at how many times the petrol price has been changed, cost of diesel and others.”

He recommended that the drug list should also be reviewed. “For instance, if an enrollee requires a strong antibiotic, such a patient may only be given what is on the NHIS essential drug list, which are mostly ordinary drugs, not branded ones. Whereas, a doctor may wish to give such a patient a stronger antibiotic, like Augmentin, or Beecham Ampiclox. But because such is not on the drug list, we doctors, are left with no choice but to give them the drugs on the NHIS list. This sometimes may not be as effective. That is what often gives rise to patients complaining of substandard drugs.”

Advertisement

Adeyeye suggests that NHIS and HMOs should work out a modality where they have customised managed care drugs — drugs that are manufactured, good quality but tagged for managed care as in the case of PTF drugs.

‘HMOS ARE OPERATING WITH IMPUNITY’

Apart from complaints from enrollees, TheCable also found that healthcare providers are disgruntled about the operations of the scheme.

One of the payment mechanisms in the NHIS is the fee-for-service. It operates thus: a hospital gets refunded (by HMO) after treating an enrollee. This happens a lot in cases of referrals. Adeyeye says this mode of payment has never been implemented since inception.

Confirming this is a consultant paediatrician at ChildKind Children’s Hospital, Lagos.

“NHIS is weak in regulating. They can’t even control the HMOs. The HMOs are operating with impunity,” the consultant, who prefers to remain unnamed because of his civil servant status, says. On his table are heaps of files containing “treatment and claims” forms sent as evidence to the HMO in question for all patients treated in a particular month. The form contains sections indicating type of service rendered, diagnosis, lab investigations, prescription and amount/cost.

“We submit these forms every month,” he said pointing to the file on his table, but the HMOs don’t pay. We are in May (2019) now. We have not been paid since October 2018. As a result, we are finding it difficult to pay salaries of our staff, or even buy new equipment,” he said. “Nobody holds the HMOs to account, that’s why we want you journalists to help us write about these things.” According to him, NHIS funds is also supposed to be an investment in the health sector, strengthening small hospitals and clinics, and helping to develop health infrastructure across the country.

A similar complaint of the refusal of HMOs to refund the fee-for-service was noted at the General Hospital, Gbagada, Lagos. “Every month, we write to the HMOs showing them how much we have spent and the kind of treatment and prescription, but they don’t pay,” a nurse tells TheCable. “We report to the NHIS, who is supposed to regulate them, but they do nothing about it.” There are 33 HMOs using this hospital.

‘NOT AWARE OF NHIS’

TheCable also visited the University College Hospital, Ibadan, where several women at the antenatal ward say they are not enrolled on the scheme. Some even say they have never heard of it.

When the scheme was established in 2005, it was meant, amongst other things, to provide universal health coverage, which is globally acclaimed to be the sustainable development for any country’s health system. But it is very far from achieving this as many especially, in rural areas are unaware of its existence.

Ahmed Yahaya, the Osun state NHIS coordinator, admits that they are aware of the anomalies going on between the HMOs and the hospitals, but they are inadequately funded to address it.

“The enforcement team is not supposed to sit down in the office. They are supposed to be going around to look for trouble spots. But where is the fund? That is why they have not been too effective. There is little we can do. We just sit at the desk and do what we can at the desk level,” he says.

According to him, NHIS does not generate more funds from the money they collect as they used to.

“The funds are not there. The money is now in TSA (treasury single account). Insurance money is supposed to be invested, to yield more money, but we don’t invest our money and that does not enable us to generate income to do whatever we are supposed to do. Before, we used to invest the insurance money so we can generate interest. But now NHIS is not in the custody of this money. So, creating the pool of funds is getting difficult for us. What we are saying is this, allow NHIS to invest in the funds, everything will be smooth. If the fund is not out of TSA, NHIS may not survive,” he warns.

SHALL WE REPEAL THE ACT?

While Yahaya thinks lack of fund is what is making the scheme ineffective, stakeholders in the health sector all agree that the act establishing it, which makes health insurance ‘voluntary’ rather than ‘mandatory’, is faulty.

According to them, you cannot make health insurance voluntary and expect to achieve universal coverage. They are also of the opinion that repealing the act and establishing a new one will take care of other operational issues such as the powers of the governing council, leadership and regulatory functions.

To this end, a bill to repeal this act and establish a new one passed the second reading in October 2018. The bill seeks to enact a National Health Insurance Commission, rather than a “scheme”. In this, it redefines the powers and functions of the commission. NHIS is currently both a regulator and a player in health insurance — a rather clumsy arrangement. The amendment also, among other things, seeks to make coverage compulsory rather than voluntary.

“We need to go back to the drawing board,” Adeyeye says. “Delayed payment especially from HMOs, denial of some payments under the fee-for-service arrangement, powers of the governing council, review of capitation, all need to be addressed, otherwise even the state health insurance schemes cannot work.”

Health insurance is globally accepted as a trustworthy way of improving the health status of a country and bringing its people out of poverty. With the case of Nigeria, the implication is increased poverty, as poor people have to pay out of their pocket each time they visit the hospital. When they don’t have the money, they may self-medicate, seek alternative medicine, patronise religious houses for healing or watch their loved ones die — deaths that could have been prevented if there was money. A recent report by the United Nations says that around 98 million Nigerians are now living in multidimensional poverty.

A recent World Bank study also reveals that globally, 100 million people are pushed to poverty yearly owing to out-of-pocket expenditure on health. Similarly, a Bill and Melinda Gates-funded research, published in The Lancet — a peer-reviewed medical journal — reveals that 8.6 million people die every year because they are not covered by health insurance. Nigeria has been ranked as the poverty capital of the world, and President Muhammadu Buhari, in his last Democracy Day speech, vowed to lift 100 million people out of poverty. The lack of healthcare financing, as it is with NHIS, is one quick way of making the people poorer and more powerless.

Nigeria is among the WHO member countries that have committed to achieving universal health coverage by 2030. But this is still a very distant dream. The implications are clear: a weak health sector, where two-thirds of primary health centers are dysfunctional, where the burden of health expenditure impoverishes, and the poorest, and even middle-income citizens, die needlessly.

AGENDA FOR THE NEW NHIS BOSS

Under the leadership of the new executive secretary, Mohammed Sambo, practitioners are expectant that he would look into these issues and act immediately to address them.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not the views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment