DANSA-Agro-Oban

BY UCHENNA IGWE

This story was produced with support from the Rainforest Journalism Fund in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

As darkness slowly gave way to dawn one Saturday in January 2024, a truck’s engine rumbled into life, upending the stillness that had endured throughout the night. A few men gathered around the vehicle as they made final preparations before the driver set out to ferry his timber load – one of many to leave the community this weekend.

The truckload of timber is the result of “over 13 weeks of hard work,” said John Bassey. Bassey and other loggers stormed the forests in Oban with roaring chainsaws, felling trees and carving the logs now stacked in the back of the truck.

Advertisement

Situated in Akamkpa LGA of Cross River state in southern Nigeria, Oban is one of Nigeria’s most forested areas and houses a large part of the nation’s remaining rainforest. Considered a top global biodiversity area, the 557,682-hectare reserve stretches across the Oban Forest Reserve and the Cross River National Park.

However, these forests are fast disappearing. According to data from Global Forest Watch, a global forest monitoring system, 11 per cent of the tree cover in Oban and other areas in Akamkpa was lost between 2001 and 2022. Much of the deforestation is due to widespread logging activities by individuals, small groups, and larger business interests.

For residents like Bassey, logging has been a means to earn a living and cater for families. “I couldn’t find a job after leaving the polytechnic in 2007, so I joined the [logging] business,” he said. But barely a year later, the then-state governor, Liyel Imoke, banned forest use. The ban, Bassey said, disrupted his livelihood and that of many others in the area who were in the logging business, taking him “back to square one.”

Advertisement

The state government established the Anti-Deforestation Task Force (ATF) to enforce the ban, with members drawn from the police and other security agencies. The unit went after small-scale timber loggers like Bassey, arresting them and confiscating their timber. Even families who relied on the forests for their domestic use were not spared, as reported by PREMIUM TIMES. Many were arrested and, in some cases, brutalised for fetching firewood and picking Afang (a vegetable) for cooking.

However, as the task force cracked down on families and the local timber market, they looked away as large agribusinesses openly felled forest trees and moved truckloads of timber out of the state. Nothing more highlighted the unit’s selective enforcement of the ban. Backed by forest-clearing concessions granted to them by the Cross River state government, ostensibly to clear land for their agricultural operations, these big businesses engaged in large-scale logging in forested areas across the state.

PREMIUM TIMES’ months-long investigation found that Dansa Agro-Allied Limited, a company owned by a member of the Dangote family, led a massive deforestation drive in the Oban National Park community.

“That was a time when the government had banned logging. Nobody, no son of this soil, was even logging again. So there was a protest. People were annoyed that the government allowed Dansa. That time, if they [the government] saw you with even one log of wood, they would arrest you, but Dansa was loading out trucks of wood every day,” Felix Itambu, an environmentalist in the community, said.

Advertisement

FROM PINEAPPLES TO TIMBER LOGGING

Registered in 2005, Dansa Agro-Allied Limited (DANSA) is an agricultural company specialising in fruit processing, especially fresh cayenne and MD2 pineapples. Established by the late Sani Dangote, former vice-president of the Dangote Group and brother of Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote, the company, along with others in the DANSA value chain, has been described as part of the larger Dangote Group over the years. Sani Dangote died in 2021.

To expand its juice production line, DANSA acquired about 75,000 hectares of land in Isoba Oban between 2005 and 2006 to set up a pineapple plantation and processing plant. To get the procured land ready, the company had to clear the site, most of which was forested, cutting down trees and shrubs. Although there was a statewide logging ban in force at the time, the concession granted them by the Cross River State Government (CRSG) permitted them to deforest the area to make way for their intended agricultural operations.

After cutting down trees, the company moved an inch further, processing the timber into charcoal, which they sold off. The company had justified it as a product of “salvage logging,” a position re-echoed by Ntufam Mbey, the traditional leader of Oban. “They did that because of the timber they [DANSA] fell within the area they were to plant the pineapples, and they didn’t want to waste the timber, so they went into using the fallen trees for charcoal,” Mbey told PREMIUM TIMES.

Advertisement

However, after clearing the site and planting the pineapples as intended, DANSA continued cutting down forest trees, moving from processing charcoal to extracting timber for furniture production, divesting from its pineapple business into a full-fledged timber logging operation for close to a decade.

The company went after the area’s Apa, Ebony and Aquamiri hardwood trees and established a highly mechanised sawmill – described by locals as the largest in the state – where it produced treated wood, chairs, doors and other furniture.

Advertisement

“They were taking them to Europe, western Nigeria, and northern Nigeria. Trucks used to come in here and take the treated wood, treated doors and treated beds. Nobody could afford those doors or beds in this place,” Itambu said.

DANSA did not deny selling wood, which it claimed was merely a product of its site-clearing operations. However, the company did not provide a formal response to questions from a PREMIUM TIMES reporter in 2016.

Advertisement

Perhaps due to the differences between wood logging and fruit processing, timber “plantations” often operate under a different identity. In DANSA’s case, it was MPS Limited, also owned by DANSA’s chief executive, Sani Dangote. Thus, while DANSA ran the pineapple plantation, its sister organisation, MPS Limited, operated the timber business, processing the timber extracted from Oban forests into doors and other finished products at their sawmill. Apart from locally sourced labour, the company also employed expatriates at the sawmill, sited some four kilometres from the plantation.

In 2016, the company fell out with one of its directors, Marco Zoccoli, after a deal to deliver new equipment to boost production at the sawmill fell through. Zocolli, an Italian-Egyptian, accused it of breaching his contract, an allegation the firm denied.

Advertisement

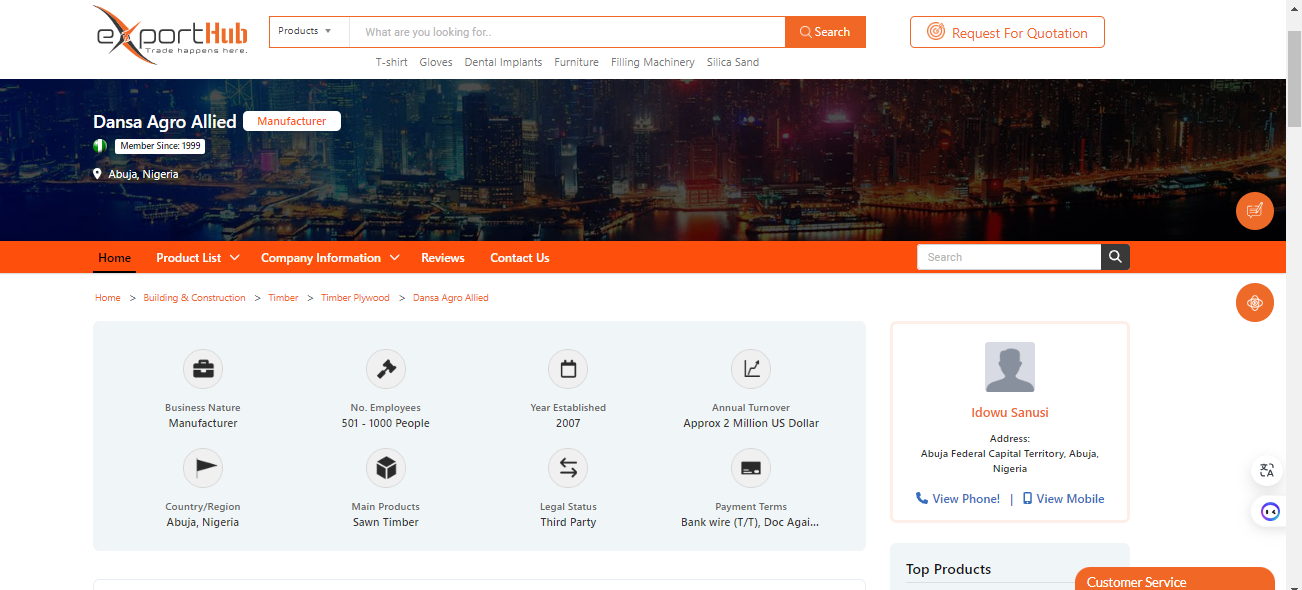

$2 MILLION ANNUAL TURNOVER FROM TIMBER EXPORTS

Despite its focus as a pineapple processing agribusiness, we found Dansa Agro-Allied Limited publicly listed as a top dealer in wood on a global trade and exports platform, ExportHub. According to the platform, DANSA recorded an annual turnover of approximately $2 million from exporting timber products, including veneer, sawn timber, plywood and block board, to Saudi Arabia, Slovenia, Thailand, the US, and the UK. It listed one Idowu Sanusi as DANSA’s contact person.

PREMIUM TIMES reached out to Sanusi for comments. While he acknowledged his stint at DANSA, he declined comments on the company’s logging and multi-million dollar timber business. “I left that company for so long, I don’t know if it still exists… or if a change of name has happened since I left the company,” he said. “I am not at liberty to tell you any information from a company I resigned from seven years ago,” he said, declining further questions. Sanusi who was managing director of both DANSA Agro and MPS at the time, also served as Executive Assistant to Sani Dangote, the owner of both companies.

When contacted, the management of Dansa Agro-Allied Limited acknowledged the company’s timber business in Oban but said that the operation did not run afoul of any laws.

“If a company has a factory or a farm, is there any law that says you cannot have a subsidiary or any other business?” Managing Director, Alhassan Maju, told PREMIUM TIMES last week. “If we see other business opportunities and establish whatever company in accordance with the law, what is the deviation that you are talking about?”

Maju said the company followed due process and received the backing of the Cross River state government which allocated land for its projects. He noted that the company was currently pursuing an out-of-court settlement to resolve its outstanding debt issues with the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON) and return to business.

DANGOTE GROUP: DANSA NOT ONE OF US

When contacted, Anthony Chiejina, head of corporate communications at Dangote Group, said DANSA was neither a subsidiary nor a member of the Dangote Group.

“DANSA is not one of us. It belongs to Aliko’s brother, Sani,” he said. “They are two different entities. They have their own management. If you check the DANSA logo, it’s not the same as Dangote.”

Chiejina noted that people often represented both companies as subsidiaries or the same entity due to the relationship between the owners.

Meanwhile, at DANSA’s operational site in Oban, Cross River state, the company’s signpost that greets visitors at the entrance bears boldly the logo of the DANGOTE GROUP, just as it does on other branded materials within the site.

EXPERTS: LOGGING CONCESSIONS ILLEGAL, ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT GRAVE

Experts have described the Cross River state government’s logging concessions to DANSA and other business interests as “illegal” and a contravention of deforestation laws. “Legally speaking, for a concession to be allocated within a protected area, the land first needs to be de-reserved (in the case of forest reserves by the CRS Forestry Commission) or degazetted (in the case of the national park by the federal government),” said George Schoneveld, principal scientist at the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR).

Environmentalists say that the logging activities carried out by DANSA in Oban degraded the forests and posed significant threats to the ecosystem. “When you talk of the area that was given to Dangote, the acreage of land that he destroyed was enormous. There were V8, V9, tractors, caterpillar trucks, and other equipment that created destruction with each print it made on the ground. If we were not in an area where desertification cannot take place easily, this place would have been a Sahel by now,” Itambu said.

Most of the pineapple plantation equipment and machines are demobilised and now litter the company’s plantation site. It is a similar sight at the company’s sawmill, some four kilometres away: tractors, forklifts, filing, ripping and sawing machines – all evidence of DANSA’s once-bubbling, full-fledged timber production business. Their site remains under lock and key after being taken over by the Asset Management Corporation of Nigeria (AMCON) over financial improprieties.

Satellite imagery from Google Earth confirmed the devastating impact of Dansa’s logging activities at the site in the Oban forest community within the period of their operations.

Another environmentalist, Odey Oyama, whose Rainforest Resources and Development Centre (RRDC) has been at the forefront of advocating against deforestation in forest-protected areas in Cross River state, consistently called out DANSA for its illegal logging activities in Oban forests, citing the company’s incursion into the boundaries of the Cross River National Park.

While the management of Dansa said they planted five trees for every one they cut down, Oyama, who once led Cross River’s dreaded ATF, described the claim as false. Multiple accounts by residents confirmed Oyama’s position. “No new trees were planted here. We can tell you that confidently. You can go around and ask people,” one resident told PREMIUM TIMES.

Replanting of forest trees is one of the sustainable mechanisms to reduce emissions and restore forest cover, a core focus of REDD+, a United Nations carbon credits project launched in Cross River state.

REDD+: MILLIONS OF DOLLARS SPENT ON ‘PREPAREDNESS’

In 2010, Nigeria flagged off the United Nations (UN) Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) project with Cross River, which holds 50 per cent of the country’s remaining rainforests, as a pilot state. The project was designed to reduce carbon (CO2) emissions and strengthen the country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

Interestingly, big businesses like DANSA in Cross River carried out large-scale destruction of the forests while this climate change project was active.

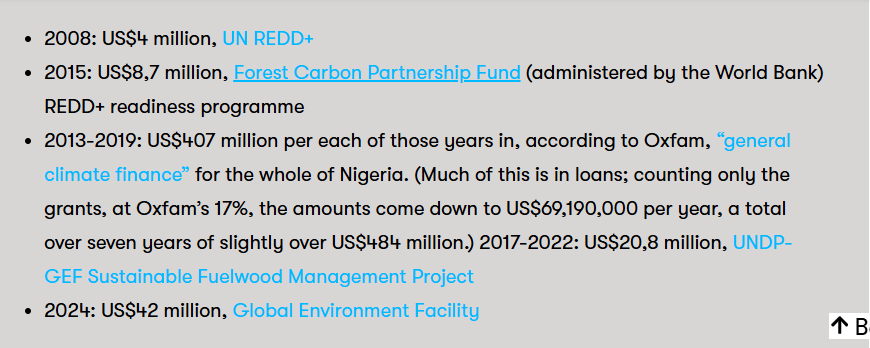

Despite huge investments, including $4 million from the United Nations in 2011 plus an additional $8.7 million from the World Bank, it would seem that REDD+ failed to meet expectations and with ‘no return on investments,’ according to Liyel Imoke, a former governor of Cross River. Lax commitment to the project under Imoke’s successor, Ben Ayade, also contributed to the project’s ailing fortunes. Nigeria also secured over $400 million from Oxfam (2013–2019), $20.8 million from the UNDP-GEF Sustainable Fuelwood Management Project (2017–2022), and $42 million from the Global Environment Facility (2024).

However, REDD+ officials disagreed that the project failed. Bridget Nkor, head of REDD+ in Cross River, explained that the project was still in the preparedness phase – the first of three phases in its lifecycle.

“Cross River state is yet to get here. Countries or sub-nationals that have completed the first two phases of REDD+ for results generated will then begin to earn credits after showing evidence of reduction of emissions,” she told PREMIUM TIMES.

Nkor noted that the REDD+ funds (about $7.7 million) were not paid to the Cross River state government but were “administered by three UN agencies: UNDP, UNEP and FAO,” on training workshops, consultancies and conferences to improve the capacity of the Nigerian government as part of the “preparedness” phase. However, the state government received $65,000 from the Governors Climate and Forests Task Force (GCF), which she said was used “to develop an investment plan that will enable REDD+ implementation.”

It has been 14 years since the UN REDD+ kicked off, and hopes of improved livelihoods for Indigenous communities through the project’s carbon credits still hang in the balance, a reality Itambu blamed the government for. “By now, the community should have been benefiting from the carbon credits, but the government still sabotaged it. How would it work when they gave the DANSA concession to cut trees and even have a sawmill with those kinds of heavy equipment?” he said.

Nkor refuted this claim. Instead, she blamed the communities – rather than the government – for granting access to forested areas after receiving financial gains. “No [government] concession of forest areas is given to any company that I know of. Communities give land indiscriminately to individuals or companies to farm, log, and mine irrespective of the area involved, whether community land or forest reserve,” she said.

INDISCRIMINATE LOGGING CONTINUES POST-DANSA

DANSA became distressed and stopped operating in the area. However, indiscriminate logging remains the order of the day in Oban, supposedly Cross River’s most protected forest area. Truckloads of timber and sawn wood leave the forests daily for neighbouring Akwa Ibom, Rivers, and other parts of the country.

Loggers spend months in the community, scouting and chopping down trees, mainly Apa, Black Afara, Iroko, Aquamiri and Ebony, in the forests.

“Wood business is all about endurance,” one logger known as Alhaji told PREMIUM TIMES in March 2024. He and his assistant had been in Oban for three months, conducting their business from a nearby motel. “I came here for Apa, but I have been here for over three months. So, that’s why I branched into [logging] other woods to keep myself busy as I wait. My boys are inside the bush working,” he said.

“Logging is profitable here, but understanding the business terrain is key. Before I entered the business properly, I had wasted over two million naira,” Alhaji said, recalling his experience as a newbie. But all that is now in the past for him.

“I have studied the town. You know, when you stay long in a place, your eyes will open. I recently saw a place where they said I can cut a truck [load of timber], but the road to the place is not yet accessible due to the heavy rainfall,” he boasted, flashing a sharp grin as he stepped away for a phone call.

Operating in Oban requires registration with the community chief, youths, and a local timber dealers’ union. “All are different registrations and can cost up to N400,000, depending on the person’s bargaining power,” Ali Yunusa, another logger, told PREMIUM TIMES. There are three logging areas here: the community forests, the wildlife reserve and the national park, Yunusa explained, each having a different level of access and prospects. Community forests are the easiest, while the wildlife reserve and national park, which hold an abundance of choice timber, require some extra effort and more money.

“They will arrest your people, and bail costs between N500,000 and N700,000,” he warned, but added that with the right bribe, a good relationship could be built with wildlife officers and park rangers. “You’ll need to settle them so that when they are coming out for an operation, they will inform you, and your boys will clear out.”

A forestry guard who asked not to be named for fear of victimisation confirmed logging activities within the national park and other protected areas. “There is a lot of logging even in the reserve areas. As we are talking now, there are a lot of people in this community who have come from faraway places for timber business,” he said.

Payment of registration and verification fees grants loggers access to the forests to confirm the availability of their choice tree/timber, sometimes with the help of a “tree finder.” Once availability is confirmed, operators at the core of the value chain cut down trees, chopping them into the desired dimensions. Motorcycles aid in commuting through the forest terrain to supervise work; in some cases, camp managers are contracted to oversee activities. After weeks of felling trees and sawing timber, loaders move the logs out of the forest and load up the trucks, ready to be hauled out.

The state’s Forestry Commission, tasked with curbing logging, has remained complicit over the years – looking the other way for a fee – as illegal loggers transport truckloads of timber out of the state every day. A director at the Forestry Commission, Frank Eja, acknowledged this in an interview with African Arguments: “Each trailer must pay N500,000,” a fee he alleged is shared among top government officials.

“We pay 500,000 naira for every truck,” logger Bassey Enoh* told PREMIUM TIMES last August as he and his crew loaded the timber they sawed over the past three months, camping here in the forest. The Forestry Commission stamp imprinted on his timber declares his truckload – one of many leaving the state today – good to go.

Although there is a subsisting ban on logging in the state, residents say poor enforcement has allowed illegal loggers like Enoh to continue to exploit the forest resources, costing the country millions of dollars in revenue. In June 2024, the state governor, Bassey Otu, announced a ban on logging across the state. Otu’s announcement came barely a year after he lifted the ban and dissolved the Anti-Deforestation Taskforce.

“They are still doing the business,” a resident who pleaded anonymity for fear of being targeted, told PREMIUM TIMES early February. “They [loggers] have started entering government reserved areas like the wildlife buffer zone” and the authorities continue to look the other way “as long as the loggers pay their dues.”

He said that the logging business was contributing to the community’s depleting forests and declining interest of its youths in education. “There is no replacement, they are not replanting,” he said. “Some of our young people have dropped out of school because of the quick money that comes from the wood business… and they don’t see the need to go to school.”

Add a comment