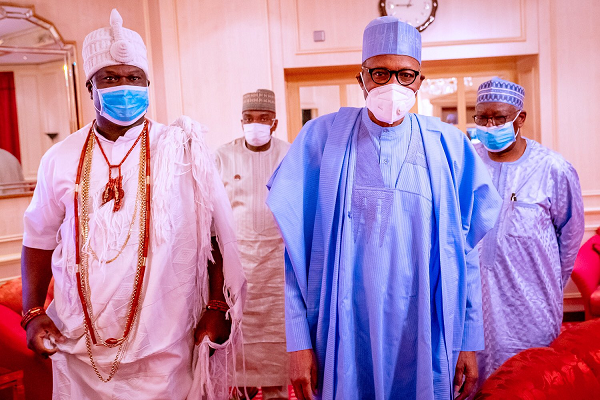

Chi, an official at Uwani General Hospital, Enugu, collecting N300 from our correspondent after giving him Yellow fever vaccine.

To ascertain Nigeria’s response to Yellow fever and Lassa fever amid the coronavirus pandemic, JAMES OJO went undercover to Enugu and Ondo — two of the country’s worst-hit states. In this report, he uncovered how extortion by health officials, lack of personal protective equipment (PPEs), shortage of health personnel, among others, affect the fight against Lassa fever and Yellow fever.

It was 7:30am on a drab Tuesday. The motorcycle screeched to a halt at Ette central health centre, after a tiring ride from Ogrute in Igbo-Eze north local government area (LGA) of Enugu state. Like others arriving the venue — a large compound with four buildings — this reporter feigned symptoms of Yellow fever and in need of the vaccine provided by the state government.

Yellow fever virus is transmitted to people primarily through the bite of infected aedes or haemagogus species of mosquitoes. While person-to-person contact is not a major risk factor for suspected cases, it is compulsory for health workers to attend to patients while wearing basic PPEs such as gloves and face masks.

Ette was one of the communities ravaged by a recent outbreak of Yellow fever in Enugu state. The community shares boundary with Kogi state, while residents speak mostly Igala and Idoma.

Advertisement

In November 2020, about 40 people were killed when Yellow fever rocked the community alongside Umuopu and other areas. Another 70 persons were also killed days after as the “strange disease”, as it was described, stretched to other surrounding local government areas.

“Please give him a seat. The nurse in charge of vaccine will soon be here,” a woman, who would later be identified as a health official, told this reporter in Idoma.

But there was nothing on ground to suggest that this was a community battling an outbreak. Just like the community itself, which lacks basic amenities, the health centre is in a shambolic state. Inside the compound were two abandoned buildings with dilapidated roofs, defaced walls and rooms almost overtaken by bushes.

Advertisement

“That building is still being used for surgery and sometimes as a labour room,” one of the women who also came to vaccinate her child against Yellow fever said. On a request to use the toilet, one was directed to a nearby bush — even though open defecation remains a major concern across the globe. The supposed toilet for the health centre and the laboratory close to it are both in a sorry state, as they have been overtaken by weeds.

Also of concern was the level of uncleanliness at the health centre. Close to the building for vaccinating people against Yellow fever were used syringes, needles and sharp objects littering the floor. At the other end of the building were used medical tools improperly disposed.

Lost in their own world, children freely played with a box containing the vaccine doses as well as other medical items left lying carelessly around the compound. Also, with the number of turkeys freely roaming about the health centre, one could easily mistake the facility for a private poultry.

FIGHTING YELLOW FEVER WITH AN OVERSTRETCHED HEALTH SYSTEM

Advertisement

About two hours later, Esther Obutu, the nurse in charge of administering the vaccine, drove into the centre and hurtled out of her car. Clad in an orange gown, she flashed a wry smile, ostensibly trying to downplay the mounting pressure. Not long after she arrived at the venue, a motorcyclist brought in a frail lady, who was placed on the concrete pavement in front of the centre, while she shivered uncontrollably. Seated beside her was a woman donning an orange-coloured hijab with her two children, one of whom she said had a serious headache during the night.

It was obvious that there were not enough health workers to tackle Yellow fever-related issues and other medical needs at the centre, but Obutu was filling the gap as much as she could.

“She (Obutu) is really trying. She is practically doing everything alone in addition to her other personal tasks outside here. I admire her courage,” one of the women could be heard saying, as they stood in a group discussing in hushed tones.

In a blink, Obutu had darted into a dimly-lit room to attend to a patient writhing in pains. She would later come outside to attend to those who came to the centre to be vaccinated against Yellow fever. But she was risking her life to do that. With no gloves, face mask, gown or other essential protective material on, she reached for one of the syringes and a bottle of the vaccine on a poorly-organised table bare-handed.

Advertisement

She was not alone. Another health official, visibly pregnant, handled the vaccine without use of gloves or any other form of protective equipment.

“Our health centre is usually very dirty and its poor state accounts for why we don’t have health officials willing to come and work here,” Julius Odo, a resident of Ette, quipped.

Advertisement

Odo explained that the lingering political tussle between Enugu state government and its Kogi state counterpart over who owns the community (Ette) has stifled meaningful development at the area.

“The situation of things here is due to the controversies surrounding our community. Kogi and Enugu are both laying claim to this place, but most of us prefer Enugu because that is the part that has been helping us the most — although some of us also get some things from Kogi. Kogi is dragging us because we speak Igala,” he said.

Advertisement

“When our health centre deteriorated, neither Enugu nor Kogi was willing to fix it. However, when the Yellow fever issue became serious, it was Enugu state that came to our aid.”

Like in Ette, there is a dearth of enough health officials to address the Yellow fever outbreak in Umuopu. When this reporter visited the only health centre in the community at exactly 9:57am during a weekday, no health official was spotted. People could be seen standing outside the padlocked building, waiting for the arrival of the official in charge of administering the vaccine. Ifebuche, a nurse who oversees activities at the centre, would later arrive but with no protective wear on — not even a facemask.

Advertisement

Speaking on her frustration with the health situation, Nkemdilim Jonathan, who said she lost Amaka, her best friend, to Yellow fever, lamented the unavailability of personnel to attend to the crowd of people thronging the health centres.

“When you visit the health centres, you will have to be really patient because they are usually a lot of people also coming to be vaccinated with a few officials available to attend to them,” she said, citing Umuopu, her community, as an instance.

At General Hospital, Ogrute in Enugu-Ezike in Igbo-Eze north LGA, the situation was no different. Only one health official was spotted attending to people who came to be vaccinated.

‘WE THOUGHT WE WERE ALL GOING TO DIE’

For Julius Odo and other residents of Ette, when they first witnessed the surge in Yellow fever infections in the area and other neighbouring communities, they thought the end had come.

“It was a terrible disease. We thought we were all going to die,” he said, wearing a defeated look.

“About 70 people died during the peak of the outbreak. They were mostly young people who died during the outbreak that rocked our communities. We had like six people dying everyday — three at Ette and three at Umuopu.

“People became afraid to the extent that we couldn’t come out again. It was at that point that the communities held a combined meeting and cried to the Enugu state government.”

“It was not long after that they brought free vaccine and started giving people. Even then, people who already had the disease were still dying. But the death rates have reduced since they commenced the vaccination and fumigated our communities,” he added.

‘N300 PER FREE VACCINE DOSE’ — HOW HEALTH OFFICIALS EXTORT RESIDENTS

It was 4:45pm on Monday. After some back-and-forth haggling on the fare, Amara Urah, a tricycle rider in Enugu, agreed to transport this reporter to Abakpa, a hustling and bustling axis of the metropolis.

Wearing a fitted red T-shirt with black hand gloves, he twisted and turned, trying to beat the usual evening traffic which was already building up. He wore a gloomy face, huffing and puffing at intervals about the situation of things in the country, saying his current situation was never his dream.

With a degree in engineering from the university, he said he least expected that he would end up driving a tricycle to eke a living. But like thousands of Nigerian graduates roaming the streets in search of job opportunities, it was a bitter reality he had to come to terms with.

Urah combines his tricycle business with another part-time job at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH) at Ituku/Ozalla, Enugu.

“I have given up on the Nigerian project a long time ago,” he said shortly after the reporter struck up a conversation bordering on politics and other issues with him.

“I have been hearing Nigeria will be great since I was young, but where is the greatness? What we have today is failed leadership, no meritocracy and talents withering away. I don’t believe this country can be great again. We are all struggling for survival.”

When this reporter asked about the Yellow fever outbreak in the state, he didn’t mince words.

“Well, the state has been grappling with the disease for a while now. However, it is a common thing in the country for our government to exaggerate figures of affected persons in situations like this just to get more allocations,” he said assertively, even without providing statistics to corroborate his claim.

“Even though the government claimed it is free, some health officials at Poly Clinic and Uwani General Hospital, Enugu, which are both owned by the government, are charging people between N500 and N1,000. This is Nigeria.”

According to him, the extortion of residents by health officials informed why he was yet to take the vaccine since the campaign against Yellow fever started in the state.

“I initially wanted to take the vaccine but when I was asked to pay, I refused and decided to let go. I have not taken the vaccine up till now,” he added.

The implication of such is that the likes of Urah in the state would stay away from taking the vaccine thereby putting the area at the risk of another outbreak.

“I learnt that they were charging people N300 at Ette when the vaccine was running out of stock. But when they brought another batch of the vaccine, they have stopped collecting money,” the motorcyclist, who conveyed this reporter from Ogrute to Ette health centre, also said.

To confirm the veracity of these claims, the listed hospitals as well as other government-owned health centres in the state were visited. At Ette and Umuopu health centres as well as General Hospital, Ogrute, this reporter found out that the vaccine was free.

At Asata Health Centre and Poly Clinic — both situated at the heart of Enugu metropolis — there was no vaccine available when TheCable visited. But at Uwani General Hospital, it was a different ball game. It was a sweltering afternoon and health officials at the hospital were having an HIV/AIDS sensitisation programme. But after explaining his mission, Urah’s words rang a bell.

“We have not started the vaccination officially here but if you pay us a service charge of N300, we can give you the vaccine,” one of the female officials said.

The official, however, wouldn’t mutter a word afterwards, probably with the expectation that her offer would be accepted or rejected. Sensing that she was losing interest in the conversation, it was agreed that the “service charge” would be paid to have a front-row experience of the extortion in the system.

“If you are ready, sit on the bench over there, I will attend to you soon,” she added, pointing to a wooden bench.

Not long after, she called another health worker — a young man — to help carry out the assignment. Clad in a well-ironed blue shirt, grey trousers and black shoes, the young man, later identified as Okpuru Chi, reached for a box containing the vaccine doses and asked this reporter to uncover his right shoulder.

After administering the vaccine, he demanded the “service charge”. A N500 note was handed to him, but the expectation of N200 change marked another episode of the day’s drama at the hospital.

“We don’t have N200 change. What do we do now?” he asked. He had barely received a response, when two other women cut in with a mixture of English and Pidgin. “Leave the change for us na oga,” they said.

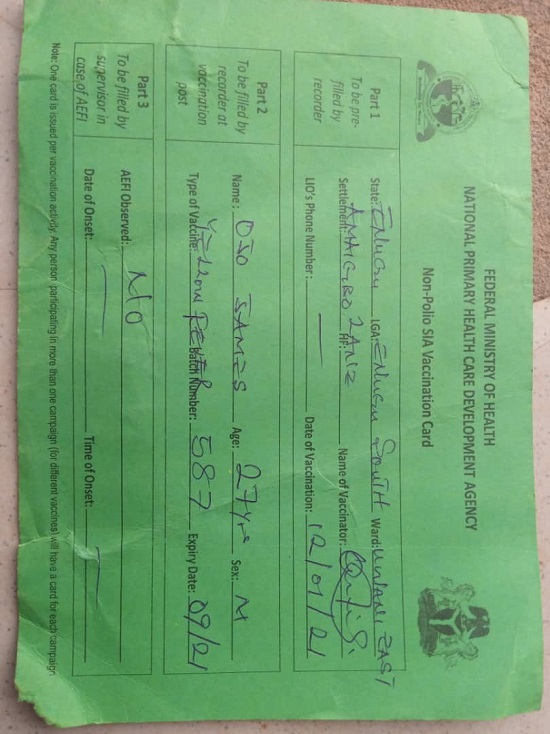

The reporter obliged and left the hospital after he was given a card to certify that he had been vaccinated.

On the card, however, there were several missing details. The name of the vaccinator was left unfilled, while the phone number of the local government inspection officer (LIO) was also conspicuously missing.

FRUSTRATING QUEUES, INACTIVE CONTACT TRACING HOTLINES… ONDO’S FLAWED FIGHT AGAINST LASSA FEVER

About 8am on Thursday, the Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Owo, Ondo state, was already packed with activities. Families and friends of patients receiving treatment at the centre thronged the gate, alongside others who also came for medical attention.

Shortly after alighting from a motorcycle, better known as okada, this reporter approached one of the security men on duty for direction to where Lassa fever-related issues are handled.

“Turn left when you get to that junction and walk down a bit. You will see the centre. In fact, you don’t need anyone to tell you when you get there,” he said.

The infection control committee of the FMC stated that Lassa fever could be managed using three approaches: contact tracing, self-report and at community level. The position of the NCDC on protecting health workers is also clear: “Do not enter a patient’s room or get in contact with a patient with suspected or confirmed Lassa fever without putting on full PPE.”

Therefore, feigning symptoms of Lassa fever, this reporter visited the infection control centre — an isolated building where people with the disease were housed — as a suspected case.

According to the NCDC, a suspected case is a “patient with fever for 3-21 days with a measured temperature of 38°C or more with one or more of the following: vomiting, diarrhea, sore throat, myalgia (muscle pain), generalised body weakness, abnormal bleeding, abdominal pain”.

Outside the building was a stationed vehicle for attending to emergencies. Close to the window was a female health official at the centre, who wore a suspicious, dreadful look shortly after this reporter told her he had been experiencing Lassa fever-related symptoms for some days, and had come for a test.

“Well, we cannot take your sample just like that. The symptoms you’re also claiming are not enough to take you as suspect. You will have to visit the general out-patient department (GOPD) and see a doctor. We would act on the report if you are examined and thereafter referred to us,” she said, expecting this reporter to vacate the premises.

From the centre, this reporter visited the GOPD unit to see the doctor. One had to first get to the revenue pay point to obtain a consulting ticket which cost N500. After obtaining the ticket came the wait for documentation, and then the handing over of a small card showing the number on the waiting list. About 30 minutes after, there was a call for documentation, after which the reporter was given a pass to another hall.

Here, one is required to undergo routine body temperature and blood pressure (BP) checks, and answer questions bordering on previous health records before finally seeing a doctor. But what ordinary should not take more than five minutes stretched into almost an hour due to the low number of officials attending to several people packed inside the hall.

Only two officials were on ground to attend to people before they were allowed to see the doctor. There was frustration on the faces of those inside the hall. After a while, it was time to see a medical personnel. Minutes after undergoing medical checks and responding to several other questions, it was time to join the final queue required to see the doctor.

It was another long ride — longer than the first. After waiting for over an hour again, a doctor simply identified as Ayodele called the next patient. Ayodele insisted that there was no Lassa fever after asking several questions. He, however, gave a list of malaria-related drugs to be gotten at a pharmacy.

The story was more or less the same at General Hospital, Alade in Idanre LGA and the University of Medical Sciences (UNIMED) at Akure, the Ondo capital — it took hours to get medical attention.

Lack of enough doctors at the nation’s hospitals has been a major issue for years with Nigeria among countries with very poor doctor-to-patient ratio, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) data as of 2013.

Shakuri Kadiri, deputy director, head of human resources at the federal ministry of health, had, in 2020, put the country’s doctor-to-patient ratio at 1:2753. This implies around 37 medical doctors per 100,000 persons, which falls short of the 1:600 doctor-patient ratio recommendation by WHO.

Aside from inadequate health officials to address Lassa fever in Ondo state, there is slow response rate in tracing contacts of suspected cases. To examine the swiftness of the state’s Lassa fever team’s response, after discussions with a female resident, a call was put through to Gboyega Adekunle Famokun. On January 20, Famokun had promised to report the case immediately to the official coordinating the response team in Owo for prompt response. But he is yet to respond more than six days after, implying that the patient could have either died or infected others around her with Lassa fever if indeed she had the disease.

ENDANGERED: HEALTH WORKERS RISKING THEIR LIVES TO FIGHT LASSA FEVER

Despite the fact that both states are among Nigeria’s top 15 most affected by COVID-19, just like findings in Enugu, most of the health workers fighting Lassa fever in Ondo had no proper PPEs on, thereby exposing themselves to possible infection. At FMC, Owo, some of the health officials attending to patients had only face mask on with no gloves. There was also poor compliance with hand washing. The situation was the same when this reporter visited the primary health centre at Ijebu ward 5, Owo, with complaints bordering on symptoms of Lassa fever.

One of the staff at the centre had taken the reporter to a mini-laboratory and consequently took his blood sample for malaria test which costs N300. However, she did the test without wearing gloves or a face mask. After completing the test, she gave a list of malaria drugs which cost N1,000.

At General Hospital, Owo, there was also poor use of PPEs, as well as low compliance with basic safety protocols. Some of the buckets purportedly stationed at the gate for washing hands had no water. At the hospital’s laboratory, where series of tests are done, an official was spotted handling some chemicals without wearing face mask or gloves.

While the situation above may raise concern, that of General Hospital, Idanre was worse.

At about 8am on January 22, there was mild confusion as health workers prepared to set up their offices in anticipation of patients.

To see a doctor here, you need to pay N1,000 for consultation/card. But that’s not all. People were asked to also pay N100 for hand gloves to be used by the health officials.

“Why won’t it be compulsory? Pay your N300 if you need medical attention here,” a visibly rankled woman documenting people’s details at the hospital’s out-patient department fired back at a boy who had earlier challenged the rationale for forcing people to pay for gloves.

To find out what the gloves were indeed used for, this reporter joined several other people waiting to see the doctor after being given a number on the queue. After a while, a health worker signalled for a blood pressure check.

“Where are your gloves,” the medical worker asked. The reporter reached for his bag and brought out the gloves sold at the revenue collection unit, attempting to wear them. But the official collected them and consequently put them on before proceeding to check the BP.

A 2018 study had examined knowledge of Lassa fever and use of infection prevention and control (IPC) facilities among healthcare workers during the outbreak of the disease in the state. Findings from the study showed poor knowledge of IPC among the health workers in Owo and Ose local government areas, despite leading the fight against the epidemic.

“Among these health centres that serve as point of first contact with possible cases of Lassa fever (LF) in these endemic LGAs, none met the minimum standard for IPC. We recommend that IPC committee for each LGA and the whole state should be set up and IPC trainings made mandatory,” the study concluded.

YELLOW FEVER AND LASSA FEVER: NEGLECTING THE ‘KILLERS’ AMID COVID-19

Yellow fever is not new in Nigeria. According to a 2020 study, the earliest outbreak of the disease in the country was recorded in Lagos in 1864. Data by the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) showed that the country has not completely eradicated the disease which has continued to reemerge at intervals.

On September 12, 2017, Nigeria witnessed a resurgence in Ifelodun local government area of Kwara state. As of December 5, 2017, a total of 337 suspected cases across 17 states were recorded with 47 deaths. By December 2018, the suspected cases rose to 3,902 with 580 LGAs recording at least one case, while 13 deaths were confirmed. By 2019, there were 4,288 suspected cases of the virus with 231 deaths, while in 2020, a total of 3,426 suspected cases were recorded with 17 deaths.

HOW LASSA FEVER KILLED 736 PEOPLE IN NIGERIA WITHIN FOUR YEARS

Lassa fever, a zoonotic disease, is endemic is several West African countries including Nigeria. The disease, usually passed on through food contaminated with infected rat urine or feces, was first discovered in Nigeria in 1969.

According to the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “an estimated 100,000 to 300,000 infections of Lassa fever occur annually, with approximately 5,000 deaths.”

Nigeria witnessed a resurgence of the disease in December 2016 and the disease has continued to kill people since then. Checks by TheCable showed the figures of suspected cases have been on the rise since 2016 with 2020 recording the highest suspected as well as death cases.

As of December 24, 2017, the country had a total of 1,022 suspected cases and 127 deaths across 19 states with case fatality rate in confirmed and probable cases put at 28.6 percent. The figures, however, increased in 2018 with suspected cases hitting 3,498 while 171 deaths were recorded in confirmed cases (171) and probable cases (20). Case fatality rate in confirmed cases, on the other hand, stood at 27 percent.

It rose again significantly in 2019 with 5,057 suspected cases recorded while 174 people died, pointing to a case fatality rate of 20.9 percent. Fast forward to 2020, the figures of suspected cases had ballooned to 6,791 with 244 deaths — although the case rate which stood at 20.5 percent was lower than that of the previous year (20.9).

This means that between December 2016 and December 2020, Lassa fever has killed 736 Nigerians while 308 have died from Yellow fever. In spite of the deadly nature of the diseases, the fight against them have suffered setbacks, particularly as the country grapples with the coronavirus pandemic.

Onoja Boniface, a resident of Ette, said despite the measures put in place by the state government, Yellow fever has not received the needed attention like COVID-19.

“We had issues with Yellow fever and the government came to our aid. But even after they came to our aid, people continued dying. They said the vaccination will start working after 10 days, so those people who already had the disease kept dying. But the death rates have reduced since the commencement of the vaccination,” he said.

“Honestly, they (government) are not taking the fight against Yellow fever seriously like COVID-19. What they did was just to fumigate the area and give the vaccination. Since then, they have not been coming to check the situation of things and most of these communities don’t have hospitals. Like in my community in Ette, we don’t have hospital. The only health centre we have is as good as dead. There is nothing there. So, we continue to suffer and the death rates continue to rise because there is no system on ground.”

‘GOVERNMENT NEGLECTING LASSA FEVER BECAUSE OF COVID-19′

A former chairman of one of the state chapters of the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA), who preferred anonymity, told TheCable that the state government has neglected the Lassa fever outbreak due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“Lassa fever is still with us, but government’s response to the disease is very very poor. We have been saying that severally. The government has not been responding to the Lassa fever outbreak the way it should and I think the problem is because it is not a pandemic. Lassa fever is endemic; we have it in some places, not all. I think that is what is responsible for that. Government needs to respond more because it is killing more than COVID-19,” he said.

Also speaking, a top official of the Association of Resident Doctors (ARD) Ondo state chapter, who did not want his name mentioned, said government’s response to Lassa fever has not been impressive due to COVID-19.

“In Ondo state, government response has been poor because the public outcry concerning Lassa fever is not as much as COVID-19. So, they tend to focus more on COVID-19 than Lassa fever. The government has not really paid much attention to it. The measures they have put in place so far are poor and inadequate,” he told TheCable.

‘OUR HANDS ARE FULL… WE WON’T MANUFACTURE HUMAN BEINGS’

When contacted, Stephen Fagbemi, the state’s epidemiologist, said the government is doing its best to contain the spread of Lassa fever in Ondo.

“The situation is under control. As far as I am concerned, I think we are doing the best we can. Ondo state government is taking the issue of Lassa fever very seriously. For us, Lassa fever is a very serious issue and our attention is focused on it because it is a deadlier disease for us in the state than even COVID-19 and we are not joking with it at all. All hands are on deck to make sure that we curtail its spread,” he said.

He, however, admitted that the fight against the disease has been confronted with several challenges, including shortage of health personnel.

“Well, it’s an outbreak and we are doing our best. You also know the challenges that we have. Now, we are fighting two diseases and the same people are responding. So, it is an unusual situation; the hands of everybody are full. We will not manufacture human beings.”

NCDC DG: COVID-19 DISTRACTING RESPONSE TO OTHER INFECTIOUS DISEASES… HEALTH WORKERS ARE CONSUMED

In a chat with TheCable, Chikwe Ihekweazu, director-general of the NCDC, confirmed that COVID-19 has distracted attention given to other infectious diseases, adding that “health workers are consumed” due to the situation on ground.

“We have just sent a team to respond to a cholera outbreak last week in Benue state and we continue to work very hard to detect every other infectious diseases. Yes, COVID is distracting the response to many other infectious diseases — that is just the reality,” he said.

“Healthcare workers are really consumed by this response and we need to remind everyone that there is a need to diversify our thinking and not limit all our engagements to the current challenge.”

He, however, said the agency would continue to provide the needed support to affected states, while stressing the need for infection prevention and control measures among health workers.

“So, on the one hand, I do understand and recognise the difficulty for many other infectious diseases that do require our attention. From our point, we will continue supporting the states in every way possible,” he added.

“Not only for COVID but for all the infectious diseases. But we also hope that a lot of the changes that have been improved — handwashing, infection prevention and control (IPC) — will also prevent the transmission of other infectious diseases in our country. So, yes, it has taken away a lot of attention but it has also hopefully provided an opportunity for us to prevent the transmission of other infectious diseases.”

ENUGU GOVERNMENT KEEPS MUM

When asked to speak about the state’s response to Yellow fever and the irregularities in the process, Emmanuel Obi, the state commissioner of health, said he could not speak on phone as he was attending a retreat.

He, instead, asked this reporter to forward his inquiries about the matter to his WhatsApp line. However, he has not responded to messages on the extortion by health workers, as well as lack of PPEs.

This reporter also reached out to Chinyere Ezeudu, the state’s epidemiologist, on numerous occasions but efforts to get her to talk about the issue did not materialise as of the time of filing this report.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the OSIWA. Published materials are not views of the OSIWA.