This is Ibu Osain. One of the worshipping points in the grove. This shot gives a sense of the contamination we captured on the field. Photo credit: Samad Uthman/TheCable

He first observed the previously colourless river turning brown in July 2019 while catnapping at the riverbank after fishing for the day. Prior to his discovery, Razaq Femi made at least N5,000 in daily returns from fishing along the coast of the river. But by November 2019, when the colour change had come to stay, he noticed the fish starting to dwindle, and his income took a tumble.

Femi says he thought it was a natural occurrence.

By April 2020 when most parts of the world were on lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the water, according to Femi, had completely turned brown. At that point, the 37-year-old said his fellow fishermen began to ask questions and were ultimately able to trace the contamination to the mining activities in Osogbo, the capital of Osun state.

The fishermen, over 500 of them, were not sure of what was being mined. What was clear to them was their progressively dwindling income, and after it nosedived to N200 in 2022, many abandoned Asejire in search of other rivers to make ends meet. But not Femi; he still visits occasionally in the hope that things might change while his wife’s income keeps the family running.

Advertisement

“My wife has been the one feeding me and the children. The income is now so low,” he said, evidently rattled but resigned to fate.

“I can spend hours here without catching a single fish a whole day. Before your arrival, I was just trying to see if the net had caught some fish. Nothing is inside. We need help over this river.”

Since the early 1950s, gold mining operations have been a permanent fixture in Osun state, although the majority of the activity has been illegal. The quest for gold continuously attracts commercial and artisanal miners, resulting in an influx of mining workers and labourers, predominantly from northern Nigeria.

Advertisement

And as the gold particles are sieved away from the ore, the impact is felt by the Asejire dam which supplies drinking water to some parts of Oyo and communities surrounding the Osun river.

Following the water

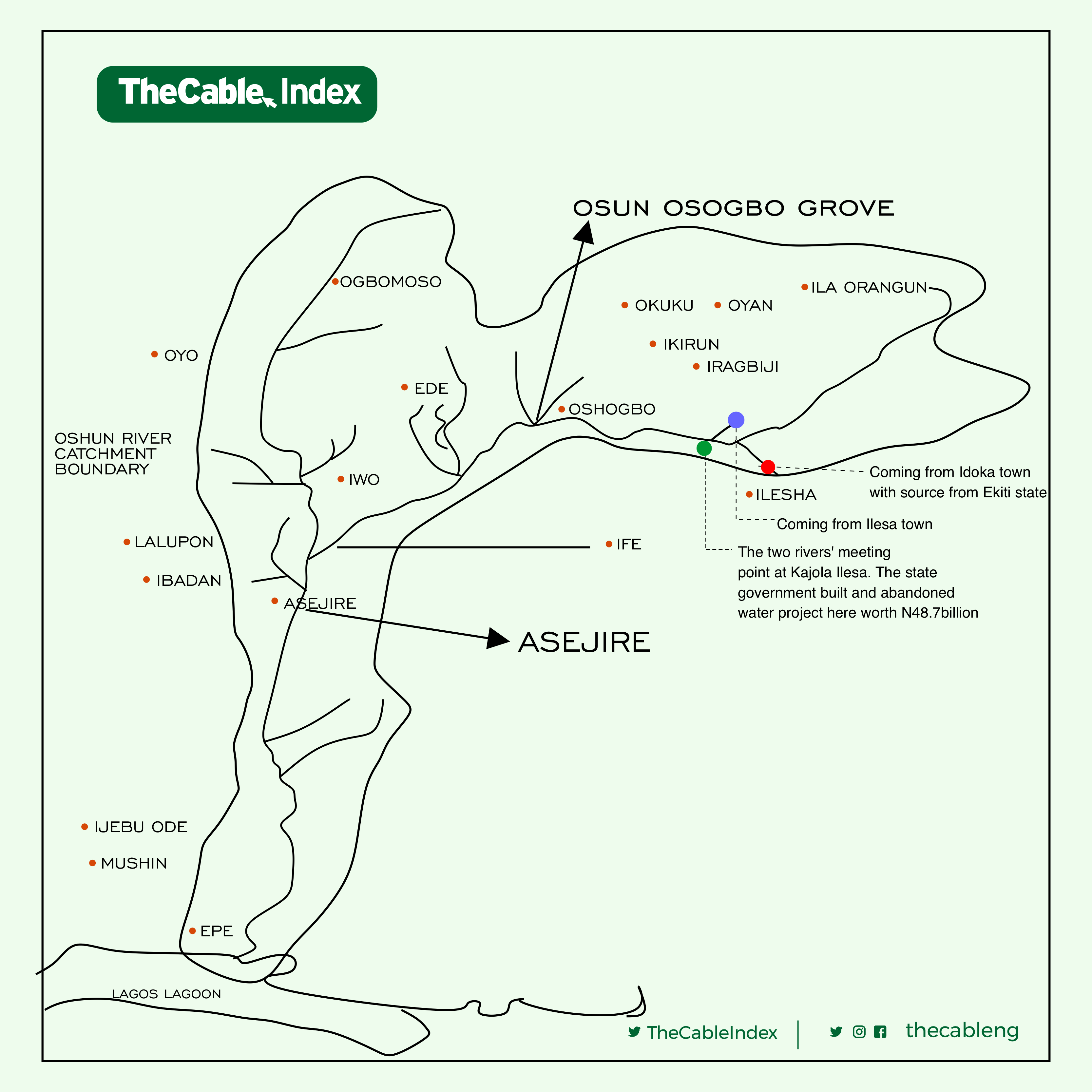

Built in the late 1960s, the Asejire dam sits on the Osun river, about 30 kilometres east of Ibadan, Oyo state. The river borders Osun and Oyo.

Using Google Earth’s satellite imagery, and with the aid of a drone, TheCable was able to trace the source of the pollution to Ilesa communities (otherwise called Ijesha) in Osun.

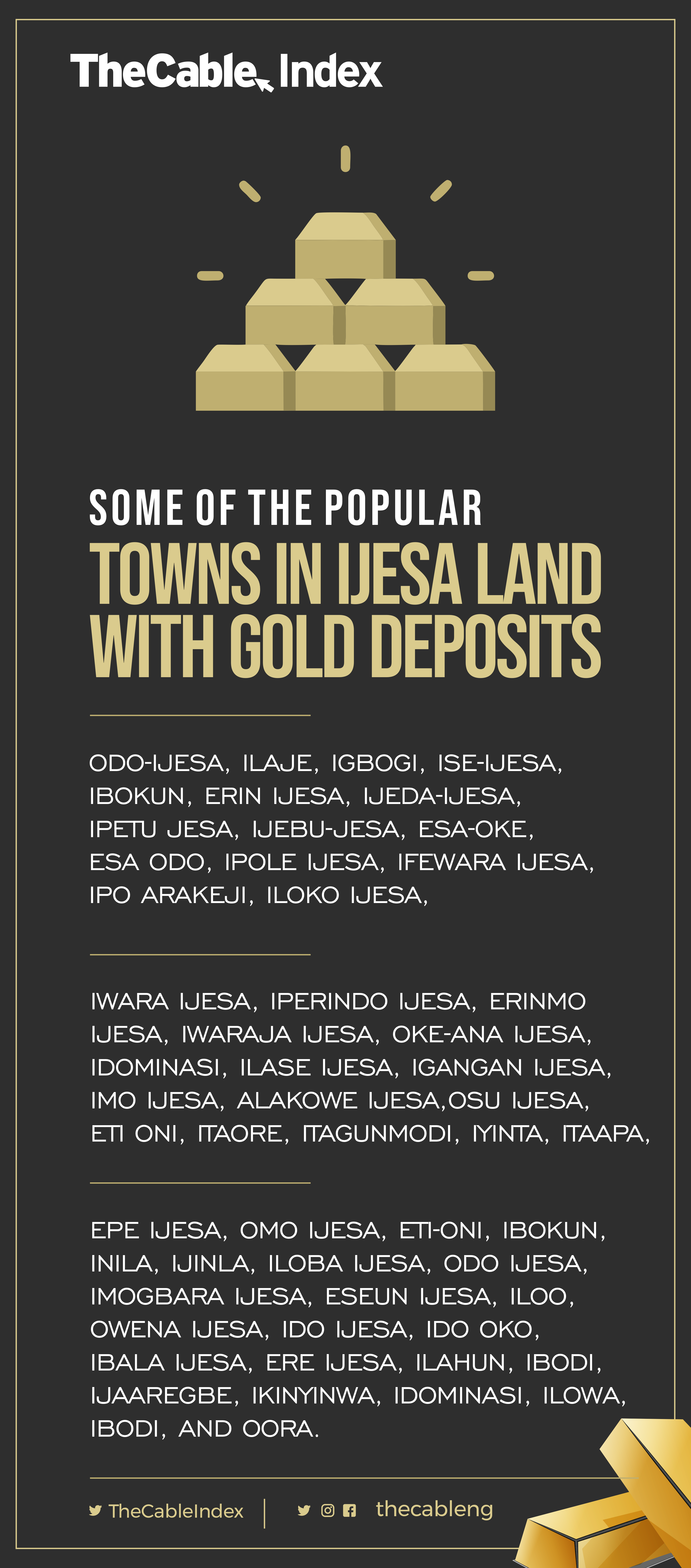

Ijesha land is renowned for large gold deposits and other minerals in considerable proportion. Due to the heightened mining activity, waste, heavy metals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and chemicals are washed into the river after the miners must have used the water pressure to separate gold from ore.

Advertisement

Large-scale surface gold mines can make use of between 60,000 and 100,000 cubic meters (16 million and 26 million gallons) of water each day.

Google Earth revealed that many rivers are tributaries of the Osun river. One of them is the Oora river in a small Ijesha village that bears the same name. The Oora river has its source in Ilesa town.

Flying at a high altitude, the drone captured an obstruction of the flow at a point on the Oora river for alluvial gold mining.

Advertisement

The main source of livelihood for Oora residents is farming, and with their water now turned brown, they are unable to irrigate their farms. Residents say before the arrival of the miners, they also relied on the water for consumption and other uses.

Ajao Ajeigbe, a car wash owner in Ilesa, said residents assumed that the change in the colour of the water was a passing phase.

Advertisement

“We all thought it’s something that will fade off in no time. You can see that it has come to stay. We use it to wash our bodies and wash cars. But we are scared to drink it,” Ajeigbe said.

Before the river turned brown, Ajeigbe said he and his family depended on it for consumption and irrigation of their nearby vegetable farm.

Advertisement

A sacred grove desecrated

The Oṣun river is named after one of the most popular and venerated deities in Yorubaland.

Advertisement

The annual traditional worship at the Osun-Osogbo grove has become a popular pilgrimage and important tourist attraction, drawing people from all over Nigeria and the world.

The Oṣun goddess is believed in Yoruba cosmology to be the provider of the needs of the people and the god of fertility.

In 1965, the Ọṣun-Osogbo grove was declared a national monument, while in 2005, it was pronounced one of the world’s heritage sites.

On the first visit to the grove, many worshippers were found milling about. One of them, Aina Oladeinde, was praying to the river goddess for the grace to win a N30 million road construction contract.

Oladeinde had travelled from Lagos for the special prayers. He credited the river’s supernatural power for his mother’s ability to conceive him after many years of being without a child, so it was only natural that he believes in the efficacy of the water. Oladeinde says whenever he drinks the water and prays with it, his wishes always manifest.

After the brief conversation, Oladeinde returned to his prayers, said a little incantation, scooped the water with his hand, and poured it into his mouth. He washed his face and arms, and then he left. After his exit, this reporter fetched the water sample at the exact spot where he performed his prayers.

Like the oblivious children swimming inside the river at a worship point called Ibu Osain, Oladeinde was similarly unbothered about the impurities that flow through the water.

Analysis of water samples

TheCable subjected the sample of the water to a test conducted by UNILAG Consult, where it was found to contain 0.034 milligrams per litre (mg/L) of arsenic, 5.663 mg/L of aluminium, and 0.090 mg/L of lead. Other heavy metals found, according to the test result, include Barium (2.326), Lithium(0.004), Nickel(2.006), and Iron(3.197).

These heavy metals were found to be significantly above the limit prescribed by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

According to the test result, the presence of these metals makes the water unsafe for consumption, bathing, and farming activities.

TheCable also collected water samples from the Asejire dam axis, a well in Akad Ilesa, and a spring in Kajola Ijesha to test for possible heavy metal percolation.

While the well water was not found to be contaminated by the nearby mining activities, there was a presence of lead and lithium in the water from Asejire.

According to information available on the Oyo government’s website, Asejire and Eleyele water treatment plants account for close to 80 percent of the total water consumption capacity of the state.

‘Biggest headache’

Adedoyin Talabi Faniyi, an Osun worshipper and adopted child of Susanne Wenger, was pounding leaves on a carved rock when TheCable got to the Adunni Olorisha building along Ibokun road in Osogbo.

Susanne Wenger, also known as Adunni Olorisha, was an Australian traditionalist who came to Osogbo to preserve the river in 1961.

Popularly known as Doyin Olosun, the priestess expressed worry over the state of the river.

“That’s our biggest concern at the moment. The moment we saw it like that some years back, we were so concerned about the cause of it. We kept asking ourselves why. We later heard it’s the effect of mining close to Ilesa,” she said.

“With its popularity worldwide, there’s nowhere in the world they don’t come to take the water. As I am talking to you, we are still in sadness, we felt it shouldn’t be like this. And the water isn’t the same as it was then. We then noticed that the mining waste has contaminated all of Osun river’s tributaries.”

But despite the state of the water, Doyin Olosun said the worshippers continue to use it for healing and spiritual purposes.

“Even with its present state, there is no day that we don’t fetch it for our daily usage in terms of making herbal concoctions and for divinity,” she said.

“Our belief in it remains the same. Still, we aren’t content with the colour.”

Danger signs

Experts say short to medium-term exposure to very high levels of arsenic in drinking water can lead to arsenic poisoning, which may cause stomach pain, vomiting, diarrhoea and impaired nerve function. Long-term exposure to even relatively low amounts of arsenic in drinking water, over years or decades, is said to increase the risk of developing certain cancers, including skin, lung, kidney, bladder and liver.

Lithium on the other hand may cause diseases of the stomach, intestinal tract, central nervous system, and kidneys.

With the presence of lead, young children and infants consuming the water are more vulnerable than adults. A dose of lead that may have an insignificant effect on adults can be more deadly for children.

In children, low levels of exposure have been linked to damage to the central and peripheral nervous system, learning disabilities, shorter stature, impaired hearing, and impaired formation and function of blood cells.

In adults, overexposure may cause high blood pressure and damage to the reproductive organs. Additional symptoms may include fever, headaches, fatigue, sluggishness (lethargy), vomiting, loss of appetite (anorexia), abdominal pain, constipation, joint pain, loss of recently acquired skills, incoordination, listlessness, difficulty sleeping (insomnia), irritability, altered consciousness, hallucinations, and/or seizures.

In 2010, a devastating lead poisoning outbreak linked to artisanal gold processing in Zamfara state killed hundreds of children under the age of five and left thousands with permanent disabilities.

Urban Alert, a civic-tech initiative leveraging technology to amplify the yearnings of the masses, said a health crisis is inevitable if the over two million people living in more than 20 communities in Osun state continue to get exposed to the contaminated water.

“In fact, our data has shown that 100,000 people may be facing serious medical challenges before 2032 if the situation is not arrested and the proper remediation process does not begin,” Anthony Adejuwon, Urban Alert team lead, told TheCable.

To determine the level of heavy metals and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the Osun-Osogbo river, some lecturers of the department of chemical sciences at Osun State University, in 2015, exposed male and female rats to the water for three weeks. The researchers found that the pollutants in the river were capable of inducing haematological imbalance and liver cell injury. The toxicity induced in blood was found to affect female rats more than males.

‘Consumption should be suspended’

The National Commission for Museums and Monuments called for a stakeholder meeting at the education/heritage building inside the grove on March 30, 2022. Ifa chiefs and traditionalists including the renowned Ifayemi Elebuibon – the Araba-Awo of Osogbo – and representatives of the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) were present.

At the meeting, the stakeholders directed that the public should desist from the consumption of the Osun river water until the pollution is resolved.

Other resolutions of the meeting include:

- Mining sublease by any licence holder (state government and private firms) should ensure that the company they sublet must have the capacity in terms of technology and reclamation plan while relevant regulators must be carried along.

- Alluvial gold mining should be suspended for now until all the issues of pollution are resolved.

- Confirmatory tests should be carried out by the Osun state government, through Osun State University, while NESREA carries out another test through the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Studies, OAU.

- The federal ministry of mines and steel development, as well as MIREMCO, should step up their regulatory activities to ensure sustainable mining.

Why Osun may continue to be at mercy of miners

Abdullahi Binuyo, deputy chief of staff to the governor of Osun, told TheCable that the inclusion of mining activities in the exclusive list of the Nigerian constitution has rendered the state handicapped. Binuyo said the state government has no regulatory power over the activities of the miners.

“I can say to you for certain that a lot of miners are in here that the state government is not officially aware of,” Binuyo said.

“Just like the oil blocs, it’s not the state government that gives it out. That is why we are partnering with the federal government to fish them out, especially NESREA.”

Binuyo said only six of the 100 mineral titles in the state belong to the state government.

“The rest of the 94 are not officially known to the state government because these are clients of the federal government,” he said, likening the state government to landlords who have no right over their lands.

He however noted that the state will do everything possible to protect the Osun-Osogbo grove and the Osun river, adding that efforts are underway to test the water for the extent of pollution.

“The issue of the Osun river is very dear to us. The grove, being a world heritage site, is something the Osun state government will do everything to protect knowing fully well the potential that it is bringing to the state on yearly basis. We cannot let that go,” he said.

The #SaveOsunRiver advocacy

To facilitate prompt intervention on the issue, Urban Alert’s Adejuwon and his team have been making spirited efforts to get the authorities’ attention.

In 2019, the team sought the service of a Geographic Information Science (GIS) expert and was able to determine that gold mining is the cause of pollution.

“We brought the issue of the colour change of the Osun River to the public space in March 2021 through the hashtag #OsunRiverPollution on Twitter,” Adejuwon told TheCable.

“The Osun state government reacted by constituting the mineral resources and environmental management committee (MIREMCO) to address the Osun river pollution and all other issues resulting from mining activities in Osun state. Unfortunately, nothing significant was seen to have been done concerning the pollution by the committee.

“The team also conducted physicochemical and microbial tests on samples collected from four different points on the water. In collaboration with senior researchers from Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, the analysis shows that the water has been heavily contaminated with mercury, lead and cyanide.”

What’s the fate of the Osun-Osogbo grove?

Many traditionalists and worshippers are worried that the level of contamination of the water may result in the delisting of the Osun Osogbo as a world heritage centre by UNESCO.

UNESCO is one of the major funders of the grove, and if delisted, the bulk of the annual funding will, by default, fall on the shoulder of the state government.

“Just like many concerned residents who wish to speak up and ensure that the Osun River is safe, I am concerned about UNESCO’s move,” Adejuwon said.

“If UNESCO delists the Osun Osogbo Sacred Grove, she will be offering the over 300-year-old grove as a sacrifice on the table of polluters and invaders.”

NESREA: We are monitoring the situation

Mohammad Maike, the Osun coordinator of NESREA, told TheCable that the agency has been mandating the mining companies to comply with the proper wastewater recycling process.

“When the alert was raised, we mobilised to the site to evaluate the level of damage. We swung into action and traced the source to Iponda. And we are monitoring the situation,” Maike said.

The state coordinator said miners have been advised to not discharge their wastewater without it being treated.

“We are trying our best. We have been on them and trying to make sure they are doing the necessary things. This includes the non-discharge of wastewater without treating it. Some of them are complying, and some of them are beginning to engage consultants who will help them. That’s what we have been doing.”

But while a permanent intervention remains pending, the pollution persists, inefficiently abated.

All efforts to get the comment of the Oyo water management board proved abortive as staff members said they are not allowed to speak to the press.

‘National security issue’

Abiodun Baiyewu, Global Rights Nigeria director, advised the federal government to declare a state of emergency on water bodies in the country.

Bayeiwu said Nigeria needs to improve its access to water policy and carry out an audit of the water bodies to ascertain the level of pollution.

“The government needs to think of this as a national security issue,” she said.

“In Nigeria, 80 percent of mining is artisanal in nature and more than 90 percent of the law addressed large-scale mining, which means that we are not dealing with the environmental consequences of artisanal mining.”

Mayokun Iyaomolere, an environmental officer and founder, Plogging Nigeria Club, said miners in Osun must be compelled to operate within the confines of best environmental practices for the protection of the water bodies.

“In cases where water pollution arising from mining operations occurs, the parties responsible must be made to carry out necessary remediation efforts to return the water to their baseline state,” he added.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.