BY GABRIEL OGUNJOBI

For more than 50 years, Nigeria’s economic mainstay has been crude oil but the oil wealth comes at a great cost: the non-renewable energy source rivals citizens’ lives and devastates the ecosystem without substantive restoration from the major players. The third part of this series looks into the activities around oil refining, and the compromise and stakes they have made for Africa’s largest nation. It delves into the inaction of the state-managed Kaduna refinery despite the far-reaching effects of the oil spill on the farmlands and water source of two communities already ravaged by bandits in Kaduna state.

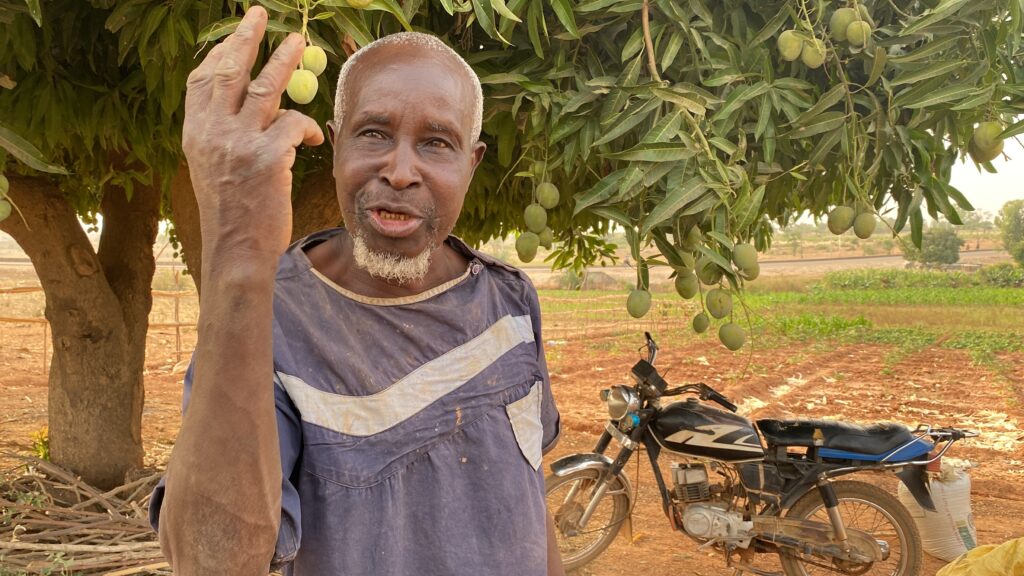

Sometimes, Garuba Usman beams his face, and his smile is contagious. At other times, a reminder of his past shrinks his face, dampening the whole mood. The 70-year-old farmer, who hails from Kaduna, suddenly began to experience a disaster on his farmland in 2021. There was an oil spill from the refinery at a stretch of less than a kilometre away from his farmland.

He is one of the 15 farmers waiting to be compensated by the Kaduna Refining and Petrochemical Company (KRPC) one year later. Kaduna refinery, like others, has been shut down since 2016. but the residents of the Kapam community in the state believe the residue of oil in pipelines was what spilt on their land during an alleged equipment failure.

Advertisement

“The people gathered names of farmers affected; but to the best of my knowledge, none of them has been compensated,” says Joseph David, the youth leader in the community.

For more than 40 years that Usman has lived in Kapam, he raised a family and built a modest bungalow from the profits he made cultivating vegetables and crops like rice and cassava.

Before he joined this reporter under the mango tree on his farm that afternoon, he alongside his youngest son was pilling cassava streaks. At his rear were beds of vegetables germinating brightly in the scorching sunshine.

Advertisement

In 2021, the farmer said he had his lowest harvest in the most recent years. Worse still, there were high expectations for that year’s farming. One of such was to betroth a wife for his son. When he could not realise that, he went borrowing.

“I barely harvested five bags of rice last year,” he stated as his luminous gesture began to fade away.

During a good season, Usman said he could harvest up to 30 bags of rice from the large expanse of land.

Kaduna has been in a dire strait for many years because of attacks by the non-state armed groups in the agrarian south of the state. In 2021, no fewer than 1,192 lost their lives to armed bandits and other forms of violence in the state, and a total of 3,348 persons were kidnapped in the same period.

Advertisement

However, the situation of a refinery caused double jeopardy for the two agrarian communities: Kapam and Rido flanking KRPC on both left and right. Usman epitomises the parlous experience the people endure; it would later lead to pent-up anger among the youths who felt cheated and attempted to protect their land.

When KADVIS accompanied the Kaduna State Urban Planning Development Agency (KASUDA) to demolish some houses on the borderline of the refinery, the people protested. KADVIS matched the protest with brute force, and one of the protesters was killed.

The community chairman, the elder brother of the deceased, refused to speak on the incident but Adamu Alkali, another protester, narrated how he survived the scuffle by sheer luck.

After the demolition of over 10 buildings on March 28, Alkali was thrown into the vigilante’s van, and driven away, bloodied. “They left me for dead in one hospital,” he claimed, threatening a lawsuit against KASUDA, upon full recovery.

Advertisement

At that moment he spoke, one of his eyes was bloodshot red, the other sealed; his occiput was bruised as he man writhed in pain on a sofa chair.

KPRC denied sending KADVIS on the demolition operation, but the community said the management has a history of not assuming responsibility even when they err — neither with the Kapam farmers nor at the second community known as Rido.

Advertisement

ABANDONED WITH A PLAGUE

Rido is less than 3km from the Abuja-Kaduna expressway which has become a home for bandits in the last few years. Not only are these inhabitants at the mercy of armed gangs using forests as hideouts, but their luck for potable water is also snatched. No thanks to the refinery, says Jonathan David, who stays at the Railway Quarters within Rido.

Advertisement

The length and breadth of this community with more than 3,000 inhabitants, according to the 2006 National Census, is by far remote, with an adjoining road to the federal highway, in between market and tad-built houses. As if to mysteriously preserve the unwholesome history of its existence, livelihood inside the Railway Quarters, on the exit wing of the community, is particularly squalid.

In January 1980, the borehole water system was launched alongside the government’s quarters built opposite the KPRC. When the minister of petroleum back then inspected the housing project, he disapproved of the idea that people should reside close by because of the environmental hazard the refinery would pose.

Advertisement

The remaining buildings were not completed but the Nigerian Railway Corporation took over the finished blocks for the temporary lodging of railway staff since there were rail tracks transporting crude from Rivers state into the Kaduna refinery.

Today, over a hundred people — both NRC staff and non-staff — live there, with a shortage of potable water.

“Each time there is an equipment failure or whatever, we see oil flowing out of the outlets into our farms,” David, a non-staff resident noted. “We started noticing traces of oil in our well”.

According to him, the borehole wasn’t working when he moved into the quarters in 2006. So, contaminated wells were their source of water.

Forensic research conducted by the trio of Louis Buggu, Funmilayo Yusufu-Alfa and Abigail Abenu for the Ghana Journal in 2020 found that the streams and other sources of water linked to the Rido river were contaminated by discharged effluents.

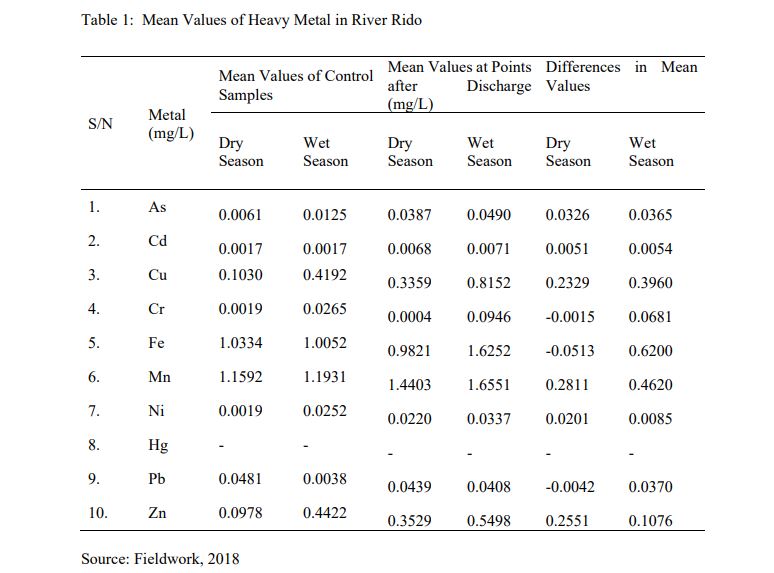

Ten water samples were collected and tested for Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Chromium (Cr), Copper (Cu), Iron (Fe), Lead (Pb), Manganese (Mn), Mercury (Hg), Nickel (Ni) and Zinc (Zn).

The results revealed that in the dry season, six heavy metals, namely As, Cd, Cu, Mn, Ni and Zn, presented mean values that were higher after the point of effluent discharge; while Cr, Fe and Pb had lower values and Hg was not detected.

In the wet season, all the heavy metals tested, except Hg, increased in values after the point of effluent discharge. The values of As, Cd, Fe, Mn, Ni and Pb after the discharge point, in dry and wet seasons, were greater than the maximum tolerable limits set by the Standard Organisation of Nigeria (SON) and the World Health Organisation (WHO). The values recorded for Zn and Cu at both dry and wet seasons were below the limit set by the Standard Organisation of Nigeria (SON) and the World Health Organisation (WHO), but the value of Cr was lower than the maximum tolerable limit only in the dry season. The contamination of the river with heavy metals poses a grave danger to human health, as its water is used for diverse purposes.

The researchers recommended that the wastewater treatment plant of KRPC should be rehabilitated and the wastewater can be pre-treated before it is discharged into the river.

Railway Quarters belly two wastewaters outlets from the refinery, making the people direct victims of oil contamination. “When the problem persisted, we shut down the wells and I personally revived this borehole with my own money. Now, we contribute to treating it whenever we detect the water smells.” David said.

The two contaminated wells shutdown is about five meters from the outlet and the borehole is even closer. With the well abandoned, the major source of water is the borehole whose purity is also erratic.

The other source sits far away at the refinery’s military lodge, off the rail link. They are not the only people depending on the tank. A neighbouring Ungwan Bulus fetches there too. Bulus was in the news on March 31. It was attacked two days after the train hijack where 20 people were kidnapped.

A railway staff, who doesn’t want to be named, said, “We have been abandoned here”. Bemoaning risks to their lives by the water they drink, yet the marauding bandits in their forest poses a bigger threat.

Garba Deen Muhammad, the NNPC spokesman, didn’t answer calls to his line for an interview on the contamination of Kaduna communities by the refinery.

With Nigeria’s regulatory failure on oil refineries, the nation’s old heritages — farming and fishing — are at a low ebb. The lack of environmental remediation across parts of Nigeria where oil is either explored or refined has advanced the advocacy to halt oil processing in the country.

While the government is yet to be accountable for the ripple effects of crude oil, communities on the fencelines of refineries suffer from these. There are particular instances of sea surges and difficulty for fishing in Lagos with aquatic splendour. Across the Niger Delta, the overwhelming menace is the lack of standard environmental clean-up, sometimes leading to sudden or steady deaths while Kaduna communities, already ravaged by insurgence, reek of soil and groundwater contamination.

The life lost over the land tussle between refinery management and the local community in Kaduna is like adding insult to the injury of the people whose farm yields are ruined by the refinery wastewater. All these devastating impacts have made ecological experts worry whether the crude oil in Nigeria is worth the risks at all or remains buried in the soil it belonged.

This report was funded under the Health of Mother Earth Foundation’s fossil politics programme. You can read the first part of the series here, and the second part here.

Add a comment