Decrepit wardrobes in the boys’ hostel barely serve their purpose

The Special Education Centre, Calabar, Cross River state, is located in a lush, quiet, and calm environment. Manicured lawns stretch out on gentle slopes, interspersed with native shrubs that lend texture and vitality to the landscape.

A visually impaired boy, around 15 years old, navigated his way to class, his guiding stick tapping rhythmically as he attempted to locate his path. He paused, momentarily unsure of his direction. From a short distance, his teacher gave gentle voice cues, helping him find his way.

The school for the visually impaired, deaf and intellectually challenged, grapples with several challenges, largely due to lack of funding. The state government only focuses on paying teachers’ salaries, relegating every other responsibility. The resources needed for the day-to-day running of the school are at the mercy of donors and the benevolence of the teachers.

Signs of government neglect are palpable everywhere in the school: dry taps, empty bookshelves, and insufficient learning aids.

Advertisement

“The government does not like doing anything. I don’t know whether it is just the government of Cross River,” a staff member, who craved anonymity told TheCable.

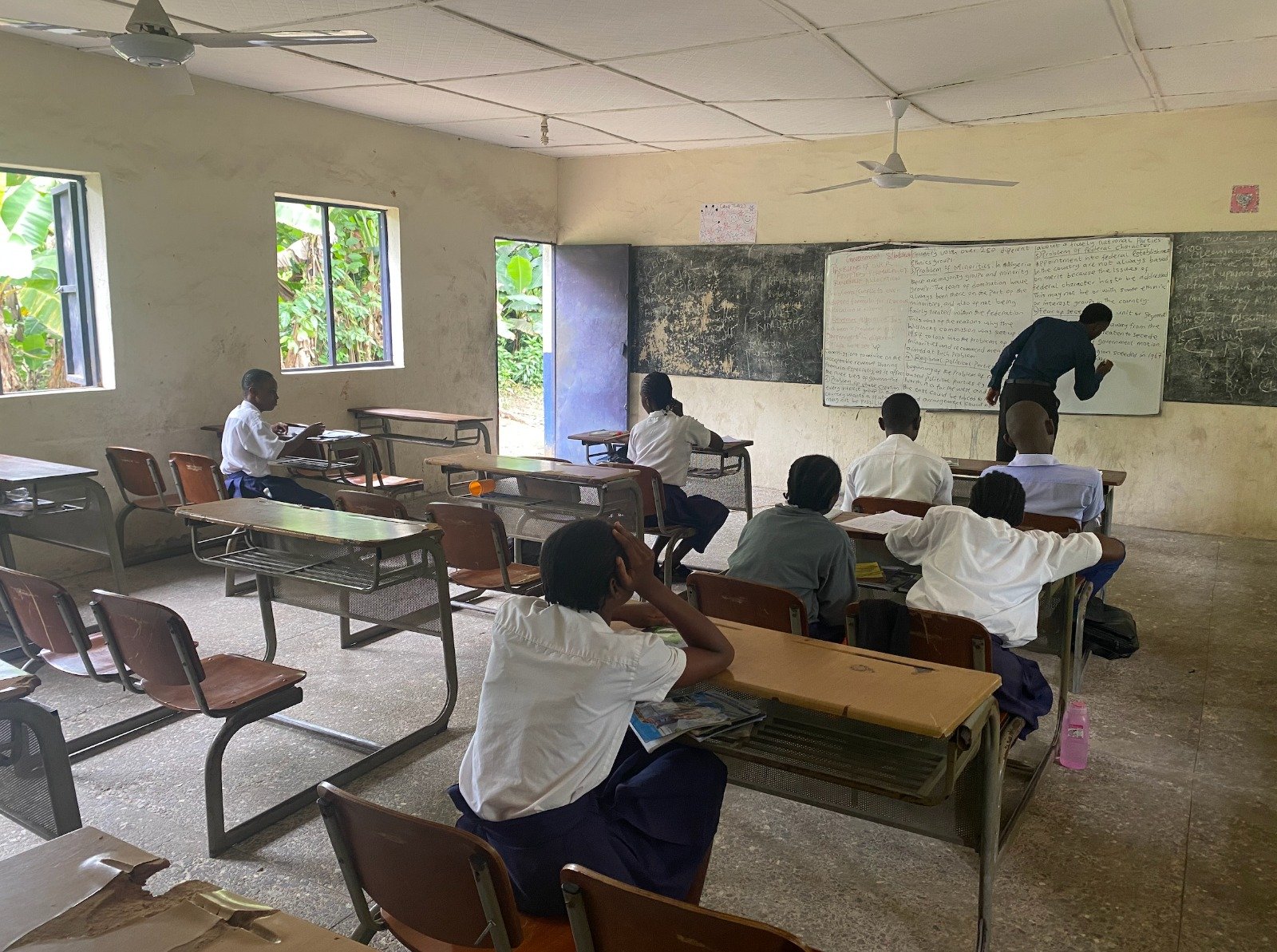

The classrooms were almost empty. The secondary school had a total enrollment of 60 students. Many of them only attended school when an examination was near. For the larger part of the term, the desks lay empty.

“Since we resumed this fourth week, coming to school has been an issue for some of our students because of distance. Transportation costs are high. Before you see most of them, it is close to exams. That is when they will start coming,” the staff member said.

Advertisement

“Many parents come with their children and ask if we have hostels. When they find out we don’t have one, you won’t see many of them again.”

As the only special education school in southern Cross River, the institution should be a beehive of activity. But the reverse is the case.

WATER SCARCITY

The school also experienced a severe water crisis that lasted over six months. In April 2024, thieves broke into the school and stole the water pumping machine. Since then, the school has been without water. The development forced students and teachers to rely on other water sources, like rainwater. Students go to nearby houses to fetch water, sacrificing valuable learning time.

Advertisement

Electricity is yet another basic need the special school lacks. Once funded by the ministry of education, the responsibility for the electricity bills shifted to teachers years ago. One teacher said on different occasions, the school complained to the ministry of education but received no response.

The monthly subvention, once a reliable source of covering daily expenses, was discontinued over a decade ago. Now, the staff rely on small contributions from parents to cover needed supplies — an unsteady and challenging situation.

The school is also battling a shortage of teaching and learning materials. On the day TheCable visited the school, a corps member needed a Christian Religious Studies (CRK) textbook for her class but none was available.

“To run the school, we ask parents for a token. When coming for admission, we ask parents to bring some materials too. This is a special needs school and they are not supposed to pay anything because the parents are already overburdened by having special needs children. So, education should be free for them – which is a government policy,” the teacher said.

Advertisement

“But as it is, we cannot run the school without money. So, we tax parents at the beginning of the school year and make sure they buy markers, and then a little money for us to buy sanitary things.”

TheCable was shown copies of several letters sent to the education ministry detailing the school’s dire situation and requesting urgent intervention but none received attention.

Advertisement

With a shortage of full-time teachers, the school rely on student teachers and corps members to fill the gaps. Yet, the assistance is limited; without accommodation, only one corps member can be taken at a time.

“We don’t have anyone to teach agriculture, physical education, or computer classes,” the teacher said. “We used to receive many requests from corps members but we only have one room available.”

Advertisement

The neglect extends to the sick bay, a company donation. No medical personnel were assigned to it, and the beds and basic furniture within were its only assets.

IN DELTA, THE GOVERNMENT ‘HAS FORSAKEN THE STUDENTS’

Advertisement

At the Special Education Centre, in Agbor, Delta state, a parent whose daughter has Down Syndrome became tearful when she started talking about the challenges faced by parents of children with disabilities.

“I don’t blame God for giving us these children. The government has forsaken us because we know in advanced countries, children with special needs, even their parents, are taken care of,” she said, sobbing intermittently. “Here, nobody cares. We cannot throw away our children because they are special”.

The school’s primary section had 62 pupils, while the secondary section had just 24 students. Due to a shortage of classrooms, the school has been forced to merge classes. This arrangement places additional strain on teachers who noted that mixed-grade classrooms limit the quality of attention and tailored instruction each student receives.

A staff member blamed the poor attendance on the school’s relocation from its previous location near the Ministry of Education at College Junction, Agbor, to its new location at the old Lagos-Asaba road.

“Many of them are not coming here again because of distance and transportation costs,” the staff member said.

“We don’t have accommodation for them. Even if we have, it’s not all the category of disabilities that we can accommodate. We can only accommodate mild ones. And maybe the visually impaired ones.”

“Caregivers too go through fatigue and burnout. This means that if you have 100 special children in a boarding school, you may need a minimum of 100 caregivers. If you see any special needs child that comes out with flying colours, somebody paid that price.”

The school was asked to vacate its former location to make way for the construction of the University of Delta, Agbor. With no place to stay, the Agbami parties came to the school’s rescue by constructing a model structure.

“We moved here because the university took our land and everything that belonged to us. They’re extending the university. They said we were sharing a common boundary with them. They drove us away,” Ezehi said.

The school has no electricity supply. The lister generator provided by the oil company is not used infrequently due to the high cost of diesel.

Similar to the situation in Calabar, the school receives no monthly subvention from the government. Essential supplies and necessities are provided by the parents or donors.

A parent who identified herself as Oweimo, the mother of 14-year-old Onyeme Michael, expressed deep appreciation for the staff’s dedication despite the absence of government support.

“Even now — past 4 pm — you can see teachers from other government offices have already gone home. But here, these teachers are still around, working hard and determined to impart knowledge to our children,” she said, her face glowing with gratitude.

Though the school officially closes at 2 pm, some students stay till 4 pm for lessons. The teachers are supported with stipends from the parents for working overtime.

The school is also understaffed. With fewer than ten teachers for the entire school, managing the unique needs of each child becomes an overwhelming task.

TheCable observed a pressing challenge in the school: children with a range of disabilities — from visual and hearing impairments to intellectual and physical challenges — all share the same classrooms. This grouping, born of necessity rather than strategy, makes teaching exceptionally difficult for the few available instructors as each child’s unique needs often require distinct approaches, specialised attention, and tailored resources that aren’t available.

“Some mothers lock their children at home and go to the farm because bringing them here every day is too much to bear. They ask themselves why they need to go through the trouble when the child isn’t benefiting fully,” Oweimo said.

In a facility dealing with complex disabilities, medical support should be a priority. But here, the lack of a medical team adds another layer of risk.

“Some students have severe conditions like cerebral palsy and may suffer from seizures lasting hours,” a parent said. “There’s no medical personnel on standby to attend to emergencies.”

STUDENTS AT THE MERCY OF MOSQUITOS IN ONDO

It was Wednesday morning, Agbele Morolayo, vice-principal of the Ondo State School for the Hearing Impaired, was beaming with anticipation as she strutted out of her office — a modest square room adjoining the school’s library.

She led this reporter — who posed as a representative of a charity — into her office.

The vice-principal enlisted the help of Olatunde, a staff member, to take the reporter around the school facilities. The decrepit situation soon unfolded.

At the library, a section of the ceiling had caved in. Termites had feasted on the structure, rendering it unsafe for teaching and learning. The walls were cracked open, visible from any angle of the room.

“Library activities have been suspended,” Morolayo said. “It’s simply too risky for the children.”

What was witnessed next would show just how bleak the reality was for the vulnerable students in this school. The second stop was the boys’ hostel.

From outside, the hostel looked like a relic of time and wear. Standing quietly under a bright blue sky, its mustard-yellow walls were worn and faded. Clothes of all colours hung on makeshift clotheslines strung between poles, each piece swaying gently in the breeze — shirts, towels, trousers — all telling of the simple living of the young boys who called this place home.

The doors were metal and chipped, leading into rooms that held more than just belongings. Shoes lay scattered on small concrete slabs near the doorways, left behind as though their owners had rushed off to something more important.

A frail-looking housefather was called upon to unlock the hostel, and when we entered, the extent of the decay was shocking.

Broken floors and torn window nets, framed rows of rickety bunks atop which lay filthy and torn mattresses. The wardrobes were decrepit, their doors barely hanging. A small part of the ceiling was torn open, and the wooden beams struggling with termite damage. The environment was little more than a breeding ground for sickness.

‘MALARIA ACCOUNTS FOR 90 PERCENT OF SICKNESS’

She pointed to the windows, saying: “You can see how torn the window nets are. This is how the mosquitoes get in”. She said the hostel was a breeding ground for sickness with “90%” of the cases reported at the school’s clinic as malaria.

“We’re constantly treating malaria,” she said. “If we could receive help to fix this hostel, it would make a huge difference.”

The hostel also lacked enough mosquito nets. Olatunde said she prays to God every day to send the school a helper to fix the boy’s hostel.

“We’d be incredibly grateful if you could help us. This hostel needs a complete overhaul,” she said.

The clinic is an eyesore. A section of the ceiling in the medical centre had already been removed for safety. Termites had destroyed the wooden beams, making it structurally unsound.

The vice-principal said the professionals who inspected the building recommended a complete overhaul, including installing new termite-resistant coaches.

Fabiyi, a nurse, who had just finished handling medical materials when we arrived, scooped water from a bowl to rinse her hands — it was all they had. The clinic had no consistent water supply, leaving the staff to make do with water fetched in covered bowls.

Moving around the clinic’s storeroom, the sight could only leave one weak and baffled. The store had no drugs or medical supplies. Empty first-aid boxes decorate everywhere. The ceiling had also been removed. The store was another centre of termite infestation.

As we approached the kitchen structure, one thing was instantly obvious; a gentle nudge was all it needed to come crashing down. The building leaned to one side, with metal poles barely holding up the roof. Inside, the cooking area was covered in ash and soot, with splintered firewood sitting inside the makeshift cooking tripod. Blackened, soot-covered pots sat on top, and the wet floor created a hazardous, slippery environment.

“This is where we cook all our meals,” Morolayo said, looking over the soot-covered cookware. “We got a new kitchen structure last year, but gas is too expensive. So we still rely on firewood.”

The girls’ hostel, once a classroom block, had been repurposed to accommodate students. The atmosphere inside was stifling, with a musty scent lingering in the cramped quarters. In one section, rainwater had pooled on the floor, seeping in through inadequately sealed windows.

The final stop was the school bus, or what remained of it. Morolayo said the bus had been grounded for as long as anyone could remember. Without it, secondary school students had to walk almost 60 minutes daily (to and fro) to Akure High School, a journey filled with risks.

The situation at the Ondo State School for the Hearing Impaired was in stark contrast to the rights protected by law. Under Nigeria’s Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act of 2018, the government is required to provide accessible facilities for people with disabilities. Yet, the conditions at this school were anything but accessible.

IT’S THE SAME STORY IN KWARA

Nestled behind expansive stretches of land, the Iyeru Okin School for Special Needs, Offa LG, Kwara state, could easily be overlooked by passersby but for its bright yellow walls peeling with paint and stubborn weeds attempting to pop a hint of green.

Despite its humble exterior, its three blocks of classrooms, furnished with creaky desks, hold hope for families in the LGA. Here, students with various disabilities gather each day, eager but aware that learning here comes with hurdles.

“The school was established in 2012 by the LGA when they saw the challenges of the disabled students in regular schools,” Ibrahim Fausat, the headmistress for the primary arm, told TheCable.

Initially, nearly 100 pupils squatted in a nearby regular school, crammed into two classrooms and one administrative office for eight years. Now, barely 70 students struggle to make it to the school’s new site on days rationed by their parents to keep up with rising transportation costs.

“Some of the parents don’t have the means to transport them to school daily,” Fausat said.

For some of these parents, this means enrolling the children in nearby mainstream schools, even if they have to be taunted by their able-bodied counterparts.

After the institution was founded, the government set up a school-based management committee (SBMC). The committee made up of community leaders and parents, was tasked with relating problems beyond their capacity to the government for attention.

But the government is rarely responsive.

“When we started the school, we expected to have a boarding house. We tried our best to talk to the government but they did not respond,” Bello Yekeen, the SBMC chairman, told TheCable.

Another issue Yekeen said is affecting the school includes the neglect of teachers.

Rotimi Jumoke, principal of the junior secondary arm, said out of 17 teachers in the school, 11 are paid by the SBMC through contributions from the parent-teacher association (PTA).

Each month, Muyiheen Shittu, a PTA member, donates N3,000 from his N10,000 income to support the salary payments. He has been making this contribution for the last eight years.

“My wife is a visually challenged teacher at the school. She teaches braille,” Shittu said proudly while stomping his cane on the ground.

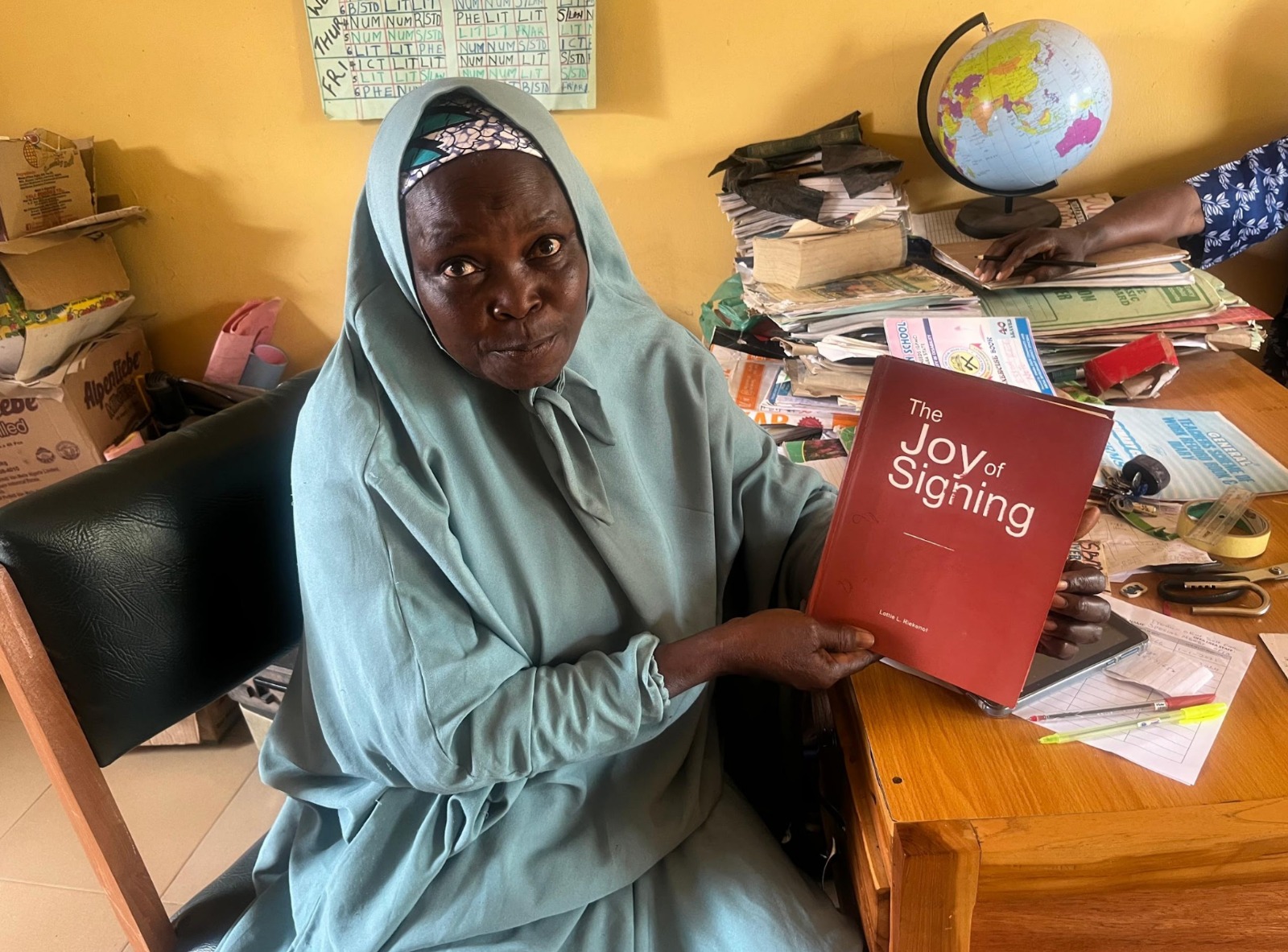

TEACHERS RELY ON TWO SIGN LANGUAGE TEXTBOOKS TO TEACH

According to the national policy on special needs education in Nigeria, teachers need to have acquired training in a pre-service teachers’ programme and are required to specialise in various areas in higher institutions.

The policy also notes that instructional materials constitute an integral part of the conception of physical facilities.

This includes general classroom materials, clinical services materials, diagnostic and assessment materials, reading texts, films, and educational and technological software that correspond with the special needs services being rendered.

When asked if these were made available to the school, Fausat replied with a sarcastic laugh. “Many of the teachers are there out of their goodwill,” she said.

The headmistress recalled a time when a school support improvement team (SSIT) trained the staff based on the children’s needs and another time when the state gathered all special school teachers for training. But these opportunities seldom happen and Fausat was not able to pin an accurate timeline on the exercises.

“One PTA staff in the primary school is trained in special education though. In the secondary school, there are two. We have a sign language textbook, which we take as our dictionary,” she said, picking up the textbook and flipping through its pages.

With only two copies, Ibrahim said teachers have to study the books to familiarise themselves with signs before each class — an opportunity to learn on the job.

The national policy also notes that special schools are supposed to be equipped with support staff including nurses, psychotherapists, school counsellors, sign language interpreters, braillers, braille note takers, braille transcribers, sighted guides, etc.

However, none of these provisions exists in all the schools visited by TheCable reporters.

IN KEFFI, A SPECIAL SCHOOL SURRENDERS ITS LAND FOR ANOTHER COLLEGE

Outside the new building initially allocated to the UBEB school but now houses the Nasarawa State College of Health Science and TechnologyThe crisp October air carried the promise of an impending downpour, intensifying just as the sun blazed down with a brightness that stabbed passersby scrambling to get to their destination. Amid the burn, students lazily made their way in and out of the Nasarawa State College of Health Science and Technology, Keffi.

They mingled with pupils from the state’s Universal Basic Education Board (UBEB) School For The Deaf, located within the same premises whose faded yellow walls bore years of wear and grime. The college students fanned their sweat-glistened faces half-heartedly with movements almost lethargic as if each step required extra effort in the sweltering afternoon.

The pupils had a different demeanour. They signed excitedly to each other, their hands moving in rapid, expressive motions with wide grins and unmistakable sounds of joy — a different portrayal of the crude circumstances they have been forced to learn under.

For nearly two decades, the UBEB School For The Deaf has tried to bridge the gap in education for children with disabilities in the state but not without its fair share of trials. Established in 2006, the school was crammed into Abdu Zanga Primary School in Keffi with three classes squeezed into a single room. To solve the challenge, the federal government allocated permanent land along the Abuja-Keffi expressway to the school.

Tanko explained that the slow process of claiming their land was due to an incomplete building at the time. Tanko Al-Makura, former governor of the state, ensured the new buildings were completed before the end of his tenure in 2019 but did not hand it over to the school. Al-Makura’s actions would cost the school its land.

When the administration of Abdullahi Sule, the current governor, came in, it boycotted the primary school and handed it over to a more “deserving” counterpart — the College of Health Science and Technology.

At the allocated building along the expressway, Tanko had envisioned that the large land would contain blocks of classes for the secondary arm, wings for boarding hostels, and staff quarters to attract both children and teachers who had boycotted the school due to a lack of conducive environment.

Now, with 88 students and just five teachers, the lack of space meant squeezing young learners with varied challenges into the same classroom.

AT LAST, ONE GOOD STORY

The eye sore of neglected state special schools is not a situation cast in stone across the country. In Lafia, Nasarawa’s capital, the story has been re-written. Situated along the Makurdi-Jos road, the Government Comprehensive Special School is a rare sanctuary for students with diverse needs.

Enclosed by towering walls topped with sharp barbed wire, its exterior is painted in soothing hues of blue and white, mirroring the clear sky above. Security here is paramount, with vigilant guards stationed at the entrance ensuring safety and privacy.

The campus is a welcoming sight, beautifully landscaped with vibrant flower beds and towering trees casting dappled shadows on the ground. Wheelchair-friendly pathways with tactile paving and handrails for added support, ensuring accessibility for students with visual impairments as well, as gracefully wind through the compound.

The school’s structure and layout appear to have been meticulously planned to prioritise accessibility, inclusivity, and efficiency. Clear signages guide visitors to specialised classrooms for hearing, visual, mental, physical, and multiple impairments.

In each classroom, staff are stationed to meet the unique needs of their students while a separate section houses administrative offices, carefully placed away from the learning areas to minimise disruptions. A dining hall sits in a corner of the vast school. Here, over 800 students are fed lunch daily. Opposite the administrative office, school buses are lined up to transport the students to and fro their homes.

But beyond this pristine facade, politics take precedence over education.

“Administrators and teachers are appointed based on their political alliances rather than their expertise,” a staff member who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the situation told TheCable.

EXPERTS: EDUCATION SYSTEM NEEDS OVERHAUL

The persisting gaps in the areas of special education in Nigeria perpetuate a cycle of underprepared educators and neglected students, trapping children with disabilities in an education system that is neither inclusive nor empowering.

To solve this, Fatima Dantata, professor of special education at the Bayero University, Kano, said there needs to be an overhaul of the country’s education structure if change is desired.

“This inclusion they keep talking of, if you look at it critically, it turns out to be exclusion because there is hardly any inclusion. It can only be seen as inclusion when all the facilities needed are made available, the personnel, the manpower, the physical structure, the budget, and the commitment to carry it out. So we need to redesign and overhaul the structure for it to be inclusive,” Dantata said.

Moradeun Oyewunmi, a professor of special education at the University of Ibadan, suggested the establishment of education bodies that will examine special students appropriately.

“There should be inclusivity and adaptations for all of them when writing exams, like a special centre. For example, if they want to write JAMB, instead of going to regular centres, there should be one that is strictly for them,” Oyewunmi told TheCable.

According to UNICEF, 15 percent of the world’s population — at least one billion people — have some form of disability, either from birth or acquired later in life. Nearly 240 million of them are children.

In response to the severe human rights violations experienced by people with disabilities worldwide, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) was adopted on December 13 2006, at the United Nations headquarters in New York.

The CRPD obligates governments to take measures to promote the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms. But despite international commitments, children with disabilities remain largely neglected in some societies.

REPORTING BY SAMUEL AKPAN, CLAIRE MOM, BOLANLE OLABIMTAN, DYEPKAZAH SHIBAYAN, KUNLE DARAMOLA, AND MONSUROH ABDULSEMIU