Kaleku Health Clinic, Kano

In its 2023 supplementary and 2024 appropriation act, the Kano state government budgeted billions of naira to purchase furniture, renovate the governor’s lodge and upgrade the deputy governor’s official residence.

However, across many communities, access to healthcare remains a challenge. From dilapidated infrastructure to a dearth of medical supplies and health workers, vulnerable populations such as women, children, and the elderly continue to pay the price. ARINZE CHIJIOKE tells their story.

In October, pregnant Amina Kabiru braced herself for the familiar long and tortuous journey from Yola Kazurawa, one of the remotest communities in Gaya LGA, Kano state, to Gaya town, where she received antenatal care. Her destination was miles away, accessible only by navigating pothole-filled, unpaved roads. Though her community once had a primary healthcare centre, it now lies in ruins with its ceilings collapsed, doors and windows shattered, and the promise of care long forgotten.

But Amina dreaded travelling on a motorcycle to Gaya for antenatal. She said it was agonising and discomforting and had led to a previous miscarriage.

Advertisement

“Travelling on foot gets uncomfortable too, especially in the heat,” she said. “But it’s not as painful as bouncing on a motorcycle with my baby.”

When exhaustion set in during the journey, she would pause to rest before pressing on, only to find herself in overcrowded hospitals where the wait for care feels endless.

The Yola Kazurawa Primary Healthcare Centre, built over two decades ago, once served as a lifeline for residents, with doctors, nurses, and health workers providing much-needed care. But those days are a distant memory. Over the years, medical supplies dwindled, health workers stopped coming, and the structure began to decay. Rainwater seeped through the roof’s missing zinc sheets and the cobweb-covered walls with moisture. By 2017, the centre had ceased to function entirely.

Advertisement

For women like Amina, the alternative is traditional birth attendants, many of whom lack the expertise to handle complications. The consequences are devastating.

“In some months, at least two women lose their children,” lamented Abubakar Ahmed, the village head of Yola Kazurawa. “Some even give birth at home, often with tragic outcomes.”

Infant and maternal mortality rates in Kano are among the highest in Nigeria, with maternal mortality standing at 1,025 deaths per 100,000 live births. According to Budgit’s 2023 State of States report, a majority (74.2 percent) of women in Kano give birth at home, a high rate attributable in part to lack of access to healthcare. While the Kano state government touts free maternal and child healthcare programmes for women in rural communities like Yola Kazurawa, this promise remains an unreachable mirage.

BROKEN PROMISES

Advertisement

Residents said Kawu Sumaila, the senator representing Kano South at the national assembly, visited Yola Kazurawa in the lead-up to the 2023 elections and promised to renovate the PHC.

Residents said he walked through the dilapidated PHC, visibly moved by its neglect, and promised to renovate it.

“He entered the PHC and saw how bad things were, but since then, we have not seen him again,” said Muktar Alhassan, a health worker in the community. “This is not the first time politicians have made promises they never keep.”

Frustrated by the inaction, delegates from the community followed up with the senator in July 2024, reminding him of his pledge. He reassured them that he had not forgotten his promise, but no visible progress had been made since the visit.

Advertisement

Similarly, state government officials visited the site in January 2023, before the governorship election, acknowledging the dire need for intervention, yet nothing has changed. Today, residents have resorted to using the staff quarters of an Islamic school, where health workers only visit on Mondays to administer immunisations.

The challenge of poor access to healthcare is not exclusive to Yola Kazurawa.

Advertisement

“The impact on vulnerable groups, especially women, children, and the elderly, is a recurring issue across many communities in Kano state,” said Musa Bello, a public health expert in Kano.

Abdullahi Kabiru, the immediate past chairman of the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA) in Kano, pointed to a systemic failure of prioritisation.

Advertisement

“Primary healthcare is the foundation of any functional health system because it is the closest and most accessible to citizens,” he explained. “It should address at least 70 percent of the population’s health needs, but that is not the case in Kano or across Nigeria.”

Kabiru, a consultant family physician, noted that the lack of autonomy for local governments exacerbates the issue.

Advertisement

“Primary healthcare falls under local governments, yet they lack financial independence. Their allocations are controlled by the state government, which decides how funds are spent,” he said.

The ripple effect of these structural challenges is devastating.

“Overburdened secondary healthcare facilities and overcrowded hospitals lead to delays in accessing care,” Kabiru added. “Ultimately, this creates a system where preventable conditions become life-threatening.”

HUMAN COST OF NEGLECTED HEALTHCARE IN JIBAWA COMMUNITY

Between 2021 and 2024, the Jibawa community in Gaya LGA suffered devastating losses.

According to Yahaya Fulani, the village head, over 15 people, including 10 children and five women, died due to the lack of access to healthcare.

“Many of these deaths could have been avoided if we had a functioning healthcare facility,” Fulani lamented.

The Jibawa Health Clinic, the only healthcare facility serving the community’s 13,167 residents, is a picture of neglect. Dilapidated and understaffed, the clinic barely meets the most basic medical needs. The walls are discoloured with brownish stains, the ceilings have collapsed, and rainwater regularly floods the rooms. Essential medical equipment and drugs are absent, leaving the clinic ill-equipped to conduct tests, diagnose, or provide antenatal and delivery care.

The situation is equally dire for patients. “The beds smell terrible because they have been used for years without replacement,” said one frustrated resident. The clinic’s pit latrine is unkempt and surrounded by overgrown bushes, forcing patients to endure unsanitary conditions.

Efforts to draw attention to the worsening state of the healthcare centre have yielded little action.

In July 2024, the Gaya Youth Awareness Association took to social media, appealing to the state government for intervention. However, this was not the first call for help. Concerns raised as far back as 2020, during the tenure of former governor Umar Ganduje, also went unanswered, leaving residents feeling abandoned and forgotten.

Currently, the clinic operates under severely limited conditions. Only one doctor visits on Mondays, from 8 a.m. to noon, to address basic needs such as conducting tests, prescribing drugs, and administering immunisations.

“We rely on medical students to fill the gap from Monday to Friday, but they lack the skills to handle complicated cases,” Fulani explained.

As a result, residents are forced to travel 10km to Gaya for medical care, spending over ₦2,500 on transportation, which is an expense many households cannot afford.

“In Gaya, we also have to pay for drugs and treatment,” Fulani said.

“If our clinic were functioning, we wouldn’t need to waste money on transport; we could focus on getting the drugs we need.”

The journey to Gaya is especially harrowing for pregnant women. “Carrying them (pregnant women) on a motorcycle is exhausting and painful. You can hear them crying out in pain during the trip,” Fulani added.

IN KALEKU, PATIENTS PAY FOR EVERYTHING

In October, 65-year-old Abdulwahab Idris was admitted to the Kaleku Primary Healthcare Centre (PHC) in Damagari, a community in LGA, after falling ill with malaria. Upon his arrival, the health worker on duty examined him and handed his sister, Amina Hairy, a list of drugs to purchase.

“They told us they had run out of supplies, so we had to get everything ourselves,” Hairy recalled.

“We bought the drugs, including drips, and even paid for transportation.”

The Kaleku PHC rarely receives regular government drug and medical supply shipments. At best, the facility gets a limited stock of malaria treatment drugs, which quickly run out due to the high volume of patients. When supplies are depleted, the staff must wait months for replenishment.

However, the lack of supplies is only one of many challenges plaguing the PHC.

“The infrastructure is woefully inadequate,” said Tijani Rabiu, the officer in charge.

The small facility is grossly insufficient for the number of patients seeking care. It has only three beds, one missing a mattress, forcing patients to share spaces meant for specific purposes.

“Both men and women end up using the antenatal care unit designed for women,” Rabiu explained.

The plight extends to the health workers. They operate in shifts, but with nowhere to lay their heads, they are forced to sleep inside the office. Five years ago, the government abandoned the structure behind the PHC, which would have served as a staff quarter. Now, it is overgrown by bushes, and the structure is already falling off.

“Whenever the walls develop cracks, we raise funds and patch them ourselves,” Rabiu said.

The PHC also lacks basic amenities like a toilet facility, compelling patients to relieve themselves in the surrounding bushes. Drinking water is unavailable, as the well near the PHC is unclean and near a contaminated river.

“We don’t conduct lab tests or handle serious cases. We desperately need the government’s intervention because working under these conditions is discouraging,” Rabiu noted.

PHC LACKS SUPPLIES, TOILET FACILITIES, DRINKING WATER

Saadata Naziru, a mother of six, has never given birth at the Sabon Layin Ago Primary Health Centre (PHC) in her community. The health workers could not attend to her each time she approached delivery.

“I had no choice but to travel to Rogo town, about 30km away, to receive care,” she said.

According to Auwal Sanusi, the officer in charge of the PHC, while the facility houses an outpatient department, an immunisation room, and an antenatal department, it lacks the basic amenities and equipment needed to serve the community.

The PHC, built in 2005, is now in a deplorable state. There are no tables or chairs, and the single bed stand available for antenatal patients has a mattress covered with a mat and carton.

“Other beds in the facility don’t even have mattresses, and the ceilings are either weak or completely open,” Sanusi lamented.

Sanusi also revealed that the PHC relies on Malaria Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) kits and malaria treatment drugs supplied by the Global Fund, as state government supplies are scarce.

“Once these supplies are exhausted, it can take months for the facility to receive replenishments,” he said.

Every Monday, the PHC organises immunisation sessions. However, the lack of a toilet facility forces women and children to relieve themselves in surrounding bushes.

“Even drinking water is a challenge,” Sanusi disclosed.

“Our well is unclean and located close to a river contaminated by all sorts of dirt. When it rains, water floods the PHC, forcing workers to seek refuge.”

POOR BUDGETARY RELEASES, GOVERNMENT’S FRIVOLOUS SPENDING

The lack of access to healthcare in Kano state can be addressed with budget accountability regarding allocation and expenditure. Sadly, budget review shows that the current administration does not prioritise healthcare delivery.

Between 2019 and 2023, Kano state consistently met and surpassed the Abuja Declaration’s target of allocating 15 percent of the budget to health. The sector received 15 percent in 2019 and 2020, 16 percent in 2021, 17 percent in 2022, and 15.9 percent in 2023. However, this trend sharply reversed in 2024, with the health sector receiving N34 billion, which represents 7.7 percent of the entire budget.

But beyond the decrease is the disconnect between allocation and releases. Analysis of the state government’s budget since 2023 shows that only paltry sums were released for budget lines related to healthcare provisions.

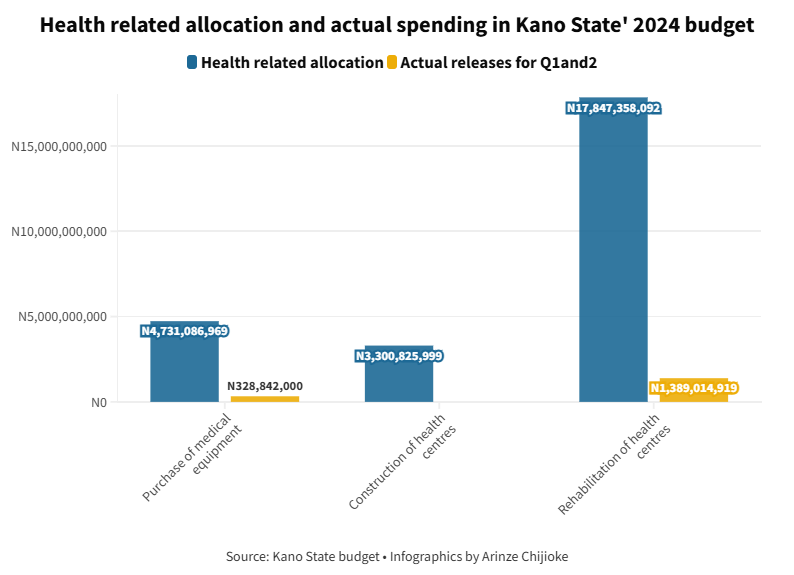

Out of the N4.7 billion budgeted for the purchase of medical equipment in 2024, N318 million was released in the first quarter (Q1) and N10 million in the second quarter (Q2), bringing the total to about N328 million. This translates to a 7 percent budgetary release.

Also, nothing was released from the N3.3 billion budgeted to construct hospitals and health centres in Q1 and Q2. Further analysis of the budget shows that of the N17.8 billion budgeted for the rehabilitation of health centres, N98.6 million was released in Q1 and N1.29 billion in Q2, bringing the total to N1.389 billion, which translates to 7.8 percent.

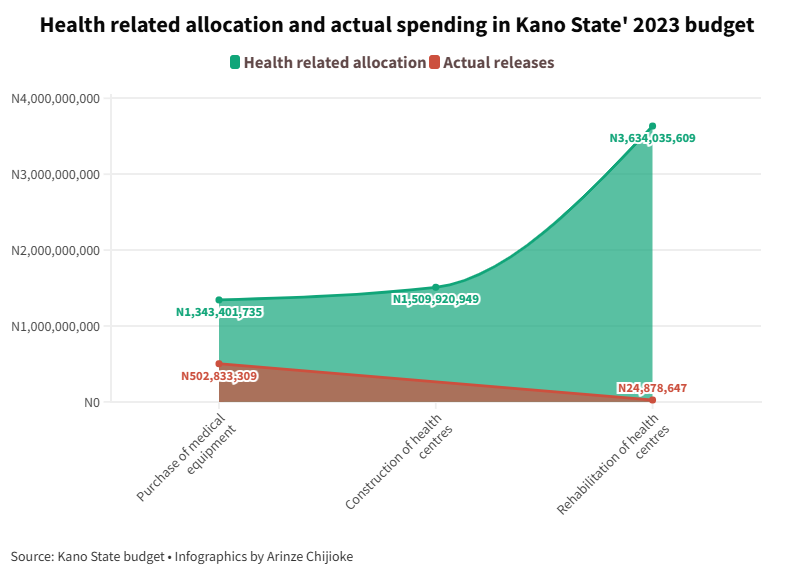

The story was the same in the 2023 budget. Out of the N1.3 billion budgeted for the purchase of medical equipment, N502.8 million was released, representing 37.4 percent. While N1.509 billion was budgeted for the construction of health centres, nothing was released. Also, out of the N3.6 billion earmarked for the rehabilitation of health centres, only N24.87 million, which translates to 0.7 percent, was released.

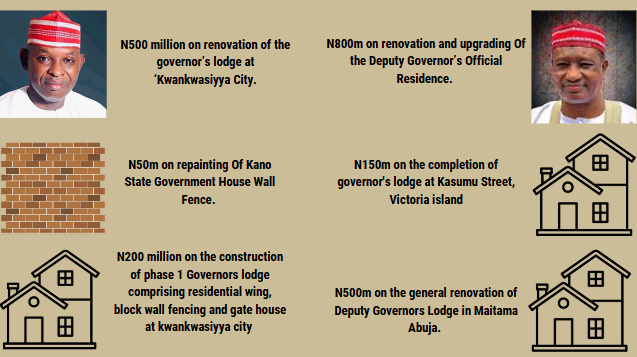

While the government allocates billions to luxury projects, the reality in underserved communities remains dire. In 2023, Kano state’s budget grew to ₦350 billion, up from ₦268 billion, following two supplementary budgets of ₦58.1 billion and ₦24 billion. By 2024, it had soared to ₦536.5 billion after a supplementary budget of ₦99.2 billion was signed into law.

“This supplementary budget is not just about increasing spending; it’s about ensuring that we meet the needs of our people,” the governor claimed in a statement.

“We are focused on infrastructural development, enhancing human capital, and making significant improvements in the health and education sectors.”

GOVERNMENT FAILS TO RESPOND TO REPORT FINDINGS

Efforts to get a response from the Kano State Ministry of Health regarding these challenges proved futile.

This reporter contacted Abubakar Labaran, the health commissioner, on November 12 and 13, 2024, but received no response. Follow-up messages were sent on November 13 and 15, and a Freedom of Information (FOI) request on November 18 also went unanswered.

When contacted, Ibrahim Abdullahi, the public relations officer (PRO) of the health ministry, redirected inquiries to the Primary Healthcare Management Board (PHCMB), stating, “We are a policy-making ministry. You can get all the information you need about primary healthcare from the PHCMB.”

On November 13 and 15, attempts to reach Nasir, the director-general of the Kano PHCMB, were unsuccessful. The Board’s PRO, Ali Abdullahi, explained, “I’ve only been here for two weeks, so I don’t have much information about primary healthcare in the state.”

ANY WAY OUT?

Kabiru emphasised the need for a complete overhaul of the state’s primary healthcare system.

“The government must invest in manpower and infrastructure to provide quality care and attract health workers to rural communities,” he said. “This would eliminate the need for residents to spend money on transport or face delays in accessing care.”

Thaddeus Jolayemi, a programme officer at Budgit Foundation, added that community leaders must take proactive steps to address these challenges.

“They can formally communicate their issues to the local government and follow up to ensure these challenges are addressed,” he said.

In a Community-Based Perception Survey conducted in Kano state between May and June 2024, the Nigeria Health Watch recommended introducing governance frameworks that include community oversight, regular performance audits, and citizen participation in healthcare decisions.

Chibuike Alagbaso, deputy director of media programmes at Nigeria Health Watch, said that people need to be active, become aware of their roles, and hold their leaders accountable for their commitment to healthcare delivery.

“While physical infrastructure such as roads and bridges are needed, we must also learn to judge leaders based on their investment in healthcare provision. People cannot travel on the roads if they are sick,” he said.

Speaking further, he said that beyond the state government, residents of communities must also begin to question what local government authorities are doing with the funds they receive as primary healthcare is under the local government.

The survey also recommended developing policies prioritising staffing in rural and underserved LGAs through recruitment drives and incentives for healthcare professionals.

This publication is produced with support from the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under the Collaborative Media Engagement for Development, Inclusion and Accountability project (CMEDIA) funded by the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment