On 9 September 2023, the Group of 20 (better known as G-20) in its summit in New Delhi, India, announced a decision to welcome the African Union (AU) as a new permanent member, effectively transforming the inter-governmental forum into G-21. September 9, the day the invitation was announced, coincides with the 24th anniversary of the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, where the African Union was announced as a successor to the Organisation of African Unity. Prior to the admission of the AU as a permanent member, it had been an invited member of the forum.

The AU’s new status with the G20 mirrors a similar status enjoyed in the group by the European Union (EU), one of the largest economies in the world and the world’s largest single market area. The EU is a permanent member of the ‘club’ alongside three of its member States – France, Germany, and Italy – and is normally represented by the president of the European Commission and President of the European Council. The G-20 (prior to the admission of the AU) represents around 85% of global GDP and 75% of global trade, as well as two-thirds of the world’s population

What does AU’s permanent members of the G-20 really mean for Africa?

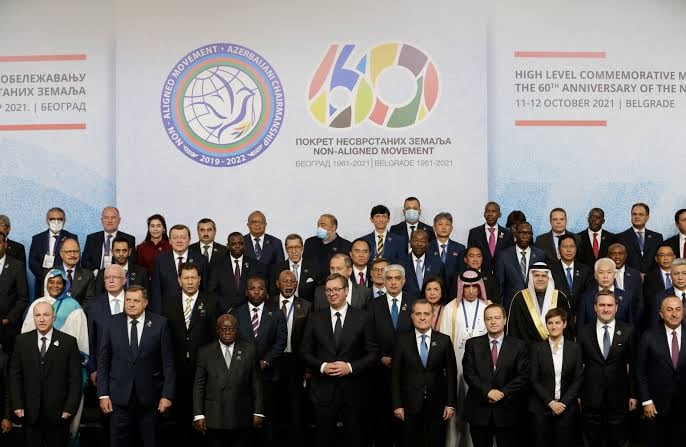

The G-20 was founded on 25 September 1999 in the wake of Mexico’s financial crisis of 1994 and the Asian crisis of 1997 when the finance ministers and Central Bank governors from the G-7 group announced that they would work together to establish an informal mechanism for dialogue with major emerging economies of the world within the framework of the Bretton Woods institutional system. It will be recalled that in 1997 major Asian countries – South Korea, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore – got into deep financial trouble after Thailand unpegged the Thai Baht from the US dollar, which in turn triggered off a series of currency devaluations and massive flights of capital. The G-20 is made up of 19 countries plus the European Union. Its establishment seemed to be a recognition of the importance of the emerging economies amid changes in the global economic landscape. The group has evolved over the years. A turning point in its evolution was the global Financial Crisis of 2008 which affected the major economies of the world, forcing them to rethink and convene a summit of the G-20 at leaders’ level for the first. A summit of the group, convened in Washington DC in 2008, was the first time that leaders of the G-20 met together because previously only the finance ministers and central bank governors met.

Advertisement

The G-20 has received as much kudos as it has received criticisms. Supporters for instance argue that since achieving implementable global goals would require joint efforts of countries, private corporations and individuals, the G-20’s ability to bring together leaders from both developed and emerging economies around the table, is, on its own, a laudable achievement. In this sense the G-20 is seen as representing a broader spectrum than the narrower perspective of the Group of Seven (G-7) which focuses on the most industrialized economies of the world. Critics have however argued that though the group was credited with helping to manage the global financial crisis of 2008, it could have actually prevented the crisis if it had heeded the warning of an impending economic meltdown by the Bank for International Settlements. Critics also argue that the G-20 Summits are often bogged down by “haggling over detailed, but often anodyne, communiqués”.

It is important to appreciate that the admission of the AU as a Permanent Member of the G-20 came at a time of increasing geopolitical rivalry in which the G-20 is seen as potentially weakened by an increasingly influential BRICS led by China and Russia, which compete with the USA-led Western nations. BRICS is a neologism coined in 2011 by the British economist Jim O’Neil, a former Goldman Sachs analyst, who used the acronym to refer to the economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China. BRIC was later turned to BRICS when South Africa was bracketed into the group in its first expansion in 2010.

Is the admission of the AU as a permanent member of the G-20 part of the competition among the various systems of geopolitical alliances – the G-7 (led by the USA), BRICS (led by China and Russia), AU, UN etc.? What is there for Africa in the AU being a permanent member of the G-20? Was the decision by the G-20 to invite the Au to become a permanent member influenced by the expansion of the BRICS group in August 2023 when it invited six countries (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt, Argentina and the United Arab Emirates) to join the group in a move described by some as an audacious acceleration of its push to reshuffle a world order it sees as outdated? Was the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi who announced the admission of the AU merely using that invitation to bolster his own profile in Africa and in the world political stage?

Advertisement

With the continent facing numerous developmental challenges – from problems of climate change, resurgence of military coups to a rise in ‘illiberal democracies’ – experts disagree on potential benefits to be harnessed from membership of the G-20. While some like Robert Besseling, Chief Executive officer of the South Africa-based intelligence advisory group Pangea-Risk believes that AU’s permanent membership “is more of a symbolic development than a substantive event” he nonetheless conceded that AU’s entry into the G20 may “help diversify global alliances and open new avenues for cooperation”. It could also be argued that membership may help to amplify African voices in global affairs because the relative loss of influence by the UN (in which Africa has the largest regional membership) in shaping world affairs to groups like G-7, G-20 and BRICS means also a decline in the continent’s voices as African countries are under-represented in the latter groups. In this sense, the G-20 could be a useful platform for Africa to potentially influence the global agenda especially on issues of international cooperation.

Though may gain from a permanent membership, The G-20 itself stands to gain even more. For instance, prior to admitting the AU as a Permanent Member, South Africa was the only African member of the body. This means that with the admission of the African Union, the G-20 (whose influence seems to be declining amid the rise in the profile of BRICS), has managed to expand its legitimacy– at least in the eyes of many Africans. By co-opting more African member countries through the AU, it has also potentially bolstered its position to compete more effectively with BRICS and other groupings that seem desirous of challenging the currently Western-dominated world order. Similarly, given the clamour for the democratization of certain global institutions such as the United Nation’s Security Council, the G-20 seems, by the invitation of the AU to become a full member, to have positioned itself as a more inclusive intergovernmental body than the United Nation’s Security Council which has five permanent members that wield veto powers.

To be able to benefit maximally from whatever opportunities full membership of the (now) G21 offers, Africa must first put its house in order. It must heal itself of the “begging bowl syndrome” and the “victim complex” because the continent cannot aspire to be treated as an equal partner in the comity of nations when it does not in truth see itself as being equal to others or when it unwittingly puts itself in subordinate relationship with other countries as it constantly shops for pity with its begging bowl. It is true that there are major constraints posed by the structure of the international system on the continent’s ability to manoeuvre but some Asian countries have shown that such constraints can be overcome. Africa needs to develop the confidence to tell itself it has come of age. There is a need for the AU to put in place effective structures and processes that will ensure that it participates effectively in all the relevant meetings of the group – not just the summit of the leaders of the countries that make up the members. The AU needs to be able to articulate and defend African interests and should not allow itself to be used to further the objectives of the competing centres of global power.

Adibe is Professor of Political Science and International Relations at Nasarawa State University, Keffi and Extraordinary Professor of Government Studies at North Western University, Mafikeng South Africa. He is the founder of Adonis & Abbey Publishers (www.adonis-abbey.com) and editor-in-chief of the SCOPUS-indexed, SCImago-ranked periodical, Journal of African Union Studies. He can be reached on 0705 807 8841(Text or WhatsApp only).

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment