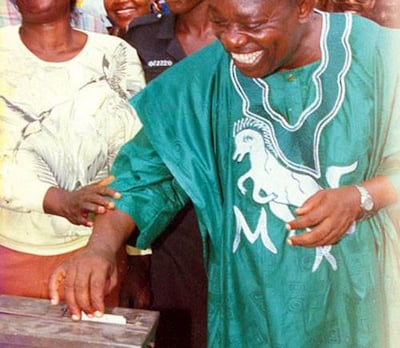

Abiola casting his vote on June 12, 1993. Babangida, whose government annulled the election, has finally admitted Abiola won

In Nigeria, June 12 is not a date, it is a consciousness. It has assumed a spirit form and any time it is mentioned it evokes emotions; it triggers some form of nostalgia. It bears a reminder that something happened, something that deprived a people of some convictions and almost threw an entity into epileptic convulsion.

The spirit of June 12 is a tenacious one. It is persistent. It haunts and tugs until it is appeased. Appeased it was on June 6, 2018 when President Muhammadu Buhari poured the libation and prayed the ghost of Bashorun MKO Abiola to rest in peace as the winner of the June 12, 1993 presidential election and stop hovering around as the presumed winner of the annulled election. It was appeased when it was declared Democracy Day in place of May 29, a date Nigeria returned to democratic governance for the third time since independence.

Buhari made the proclamation, and actualised it on June 12, this year. He ignored May 29, 2020 which would have been the first anniversary of his inauguration for a second term. There were expectations that he would make a State-of-the-Nation address. He did not. The Eagle Square was empty, not because of the COVID-19 scare but because May 29 was a no show. For now, May 29 is rested for that purpose.

The June 12, 1993 election was a watershed in the annals of general elections in Nigeria. It was an election that united Nigerians along ethnic and religious lines. It blurred the fault lines of ethnic chauvinism and religious bigotry. It proved that Nigerians can brush aside petty sentiments to embrace what they see as fit and proper. It saw majority of Nigerians moving in one direction without profiling, labelling and abusing each other. Hysteria lost its sound and solidarity travelled from north to south without being ambushed.

Advertisement

It was a revelation that Nigerians can unite if the cause is right. It revealed that any Nigerian who has proved himself worthy in industry and human relations, no matter where he comes from and no matter the creed he professes, can be accepted by a broad spectrum of people across the length and breadth of the country.

The outcome of that election showed that the problem of an average Nigerian is neither religion nor ethnicity. It proved that those who wrote Nigeria’s first national anthem and included the wordings – “though tribe and tongue may differ, in brotherhood we stand” – really understood the Nigerian psyche. It showed that those who create problems for Nigeria are few, only that they are potent in mischief.

The election featured a Muslim/Muslim ticket; something that was seen as an anathema in a cantankerous multi-religious entity like Nigeria. The marketers of religious sentiments were on duty when the ticket was declared by the Social Democratic Party (SDP). They raced to the National Republican Convention (NRC), not that they preferred its ideology; they did because they wanted to prove a point that existed only in their consciousness. There was no point to prove eventually. Nigerians disappointed them. They queued behind what they believed was likely to give the country a new lease of life.

Advertisement

Unfortunately the annulment of what has come to be known as the freest, fairest and most peaceful election in Nigeria by the military government that conducted it, almost threw the country into another round of bloody turmoil. There was no crisis during and after the election, but crisis erupted during and after the annulment. The annulment was to rewrite the country’s history in the black book of democracy. That book was never to be recommended in any democratic institution.

Characteristically, those who were not favourably disposed to the outcome of the election supported the annulment and branded the agitation for its validation as a sectional tantrum. The apostles of the religious creed jumped up and shouted hallelujah and the trenchant tribal ensemble rolled out the drums. Nigeria was on tenterhooks.

The annulment set off a chain of reactions that saw the country boiling in the West, apprehensive in the East and confused in the North. Flustered by the spontaneous rage and unsure of what was to follow, the undertakers emerged with a contraption called Interim National Government (ING) in a coffin, which was interred within the following three months by the remnant of the regime that annulled the election.

With the death of the undeclared winner of the election, Bashorun Abiola, on July 7, 1998, while still in incarceration, another chapter in the history of June 12 was opened. The wound inflicted by the annulment became deeper, making the essence of the struggle for validation more profound. With mournful mien, the apostles of June 12 who had taken their gospel to the foreign missions started a massive evangelism that saw a mass of converts chanting “on June 12 we stand”. The pitch reached a crescendo but the booming of the guns from the antagonists sent the choristers scampering abroad.

Advertisement

Those who thought the June 12 saga would go with the death of the holder of the mandate were mistaken and proved wrong once again. The wound festered and all prescriptions to heal it came to naught. They insisted the mandate must be actualised, if not physically, historically. The result must be formally declared and the winner acknowledged even if posthumously. Some buckled with the promise that democracy would return soon. It did.

Even though Nigeria returned to constitutional democracy on May 29, 1999 and the day thenceforth became Democracy Day, the relentless apostles of the annulled 1993 presidential election wanted June 12, and not May 29, to be recognised as Democracy Day. They insisted it was on June 12, 1993 that Nigeria witnessed democracy in action. It was the day the spirit of democracy seized the country from north to south. That it was on that day Nigerians abandoned creed and tribe and queued behind conviction.

Six administrations after the annulment plugged their ears. They would not hear the cry nor accede to their demands; but on June 6, 2018, President Buhari recognised Chief Abiola as the winner of an election which results were hitherto declared inconclusive; and proclaimed June 12 as the new Democracy Day for Nigeria.

If Buhari had expected a hug from all those who wore the June 12 emblem, he must have been solely disappointed. By the time the appeasement was done, some of the proponents had been scattered in different partisan political camps. They were worshipping other gods. To some of them, the validation came from unlikely quarters and must not be applauded. They made the June 12 thing look like a limited liability entity, with them as lead shareholders. Any action not endorsed by them is not valid.

Advertisement

They tried to dismiss it as being politically motivated. It smacks of betrayal. Inconsistency, if you like. The signals they emitted seem to give the impression that their initial agitation was after all not about the soul of June 12, but about their individual expectations. At every opportunity they try to drill down the notion that the validation was done for some people and not for the people. They embody the knowledge of the people. They exude the wisdom of the people. They have monopoly of righteousness. Only those things they endorse at their own time are fine; otherwise such should not be regarded. Whatever they hate, the people must hate; even when it is obvious they are strictly on their own.

Others with partisan and ideological differences saw the declaration from the same political prism, only that they believe it was an attempt to placate a supposedly aggrieved section of the country. Whatever their perspectives, the dispositions of these groups or persons must not be allowed to flourish; and they should not be encouraged to foist their prejudices on the nation.

Advertisement

June 12 should not be seen as a sectional or partisan phenomenon. It has never been and should not be allowed to be so regarded, irrespective of who is pushing the narrative. It should rather be regarded by patriotic Nigerians as a necessary move to heal the wounds of the past and redress the injustice orchestrated by the annulment of an election that was widely accepted as free and fair. It is time to move on!

The recognition of June 12 as Democracy Day should mean much more than revalidating the June 12, 1993 presidential election; it should represent justice and fairness. It should be seen as reparation, some kind of healing balm. There is a deep sense of remorse and strong spirit of restitution embedded in the act. It should therefore be seen as recognition of wrong-doing, an act of penitence and a call to fellowship. It should foster a greater sense of inclusion, peace, progress and prosperity.

Advertisement

James, a communications consultant, lives in Abuja.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

1 comments

??