With the power of assent bestowed on the president, it is very unlikely that knotty bills in the current constitutional amendment, which attempt to whittle down the powers of the executive, will ever see the light of day.

Former President Goodluck Jonathan used this power to put paid to the very expensive fourth constitutional amendment in 2015. (Premium Times reported that the committee set-up by the Senate and House of Representatives withdrew a princely 7.75 billion naira of public funds, as running cost, between 2011 and 2015, in a bid to amend the 1999 constitution.)

Expectedly, the legislature is currently exploring options on how to navigate this enormous power bestowed on the president.

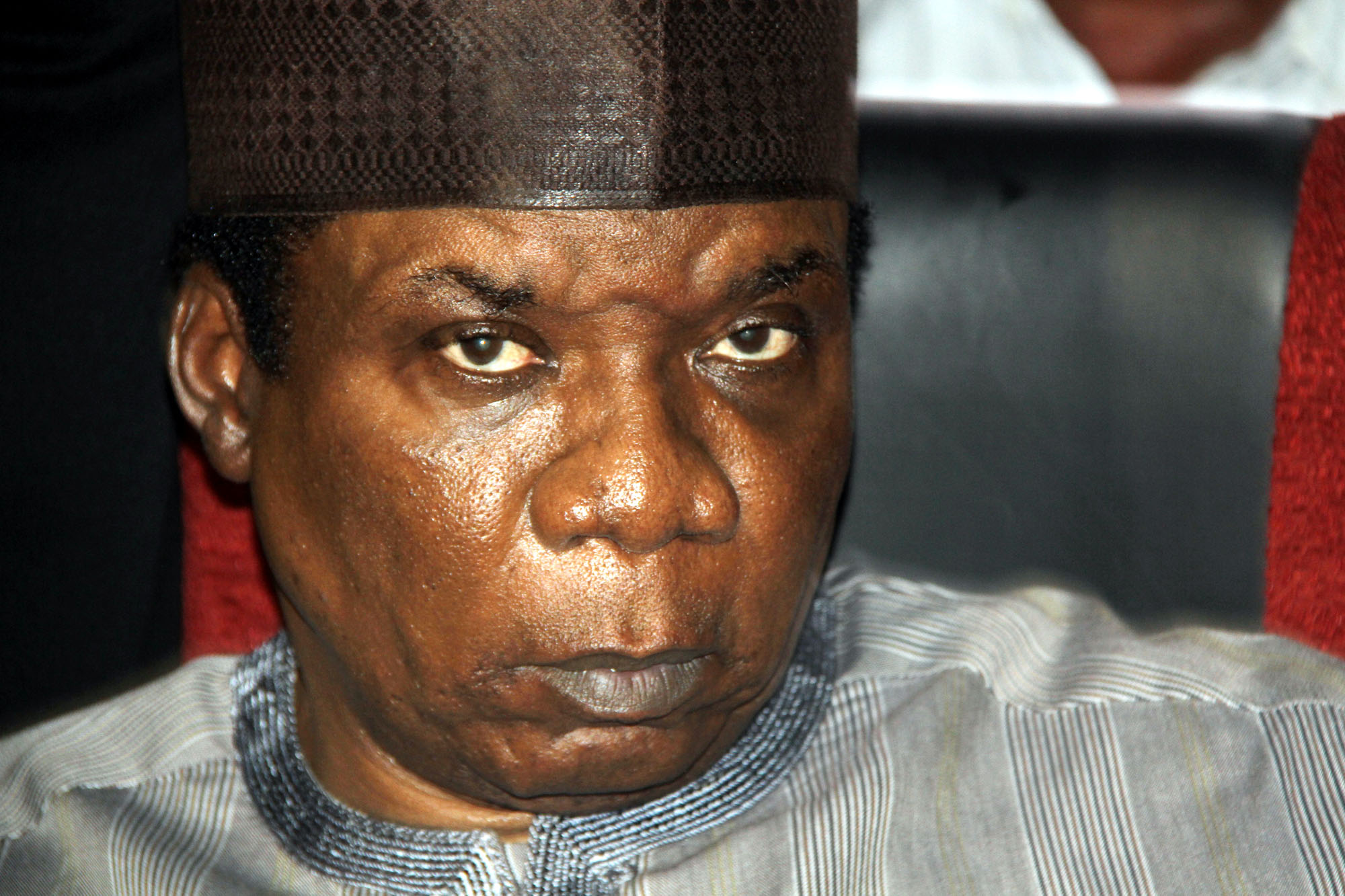

The Senate president’s recent comments show the thinking of the current assembly. “Well, to me, if two-thirds of the National Assembly agrees to something and two-thirds of the state assemblies also agree, in my view, the president should accept that as the wish of the people. Does he really need to assent? Personally, I don’t think so; that is my personal view, because with two-thirds of National Assembly, two-third of states’ assemblies, the people have spoken,’’ Senator Bukola Saraki told journalists.

Advertisement

Obviously, the Senate would have loved that U.S. laws, where the president could veto any resolution of the Congress and Senate except those bordering on constitution amendments, to be applicable in Nigeria. But this isn’t what Nigeria’s constitution says.

Unless the Senate addresses this issue, amendments which affect the way the executive carries out its business would hardly fly. These are, to some extent, the most important amendments in the current exercise.

These include amendments bordering on: the time it takes the executive to appoint ministers; assignment of portfolio to ministerial nominees before confirmation; separation of the office of the attorney general from the minister of justice; time it takes for the executive to present budgets.

Advertisement

And there is also the contentious amendment which seems to infringe on the fundamental right of a person who completes the tenure of an indisposed or dead president to run for office after such tenure expires.

Even future bills – such as those on the devolution of power and resource control — could suffer the same fate as other bills, which attempt to reduce the powers of the president.

All the president has to do is to wait for these bill to get to him. The executive knows that if it refuses to assent to any of these bills, and raises some fundamental comments, the whole lengthy process of amendment concerning the bills in question would have to start again. It doesn’t matter if the process took four years. Any exercise that takes forever to complete automatically becomes an academic exercise.

A precedence has been set in the the case of INEC v Obasanjo (2003). Here,Oguntade, JCA, (as he then was) posited: “Presumably, the Electoral Bill went through the requisite stages before it was sent to the President i.e. 1st respondent/cross-appellant for his assent. However, it was not assented to within 30 days. Under section 58(5) of the Constitution, in order to override the veto of the 1st respondent, each of the Houses of National Assembly has to pass the bill again. The language used by section 58(5) is ‘and the bill is again passed by each house.’ This means that the bill has to go through the same processes it has previously gone through when it was first passed. That is the clear import of ‘the bill is again passed’. It means a repetition of the earlier process.”

Advertisement

The Senate and the House of Representatives should pause and address the issue of presidential assent before any expensive and sensational constitution amendment is made.

Real constitution amendment isn’t going to be a judicial or legislative exercise, it is likely going to be a political exercise. One that would require a political overhaul and a fundamental restructuring of the constitution. One way would be to give constitutional backing to a truly national confab.

Add a comment