As difficult union systems progress through the comings years, their liability to encounter snakes or ladders will depend, however, not on throws of the dice, but on certain dispositions and capacity to take initiates (Crouch, 2000, p.70)

In 1848, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, the founder of scientific communism had proclaimed in The Communist Manifesto, “Workers of the World, unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains”. It is a fact that the industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Europe and North America accentuated the class divisions in society, the workers versus the owners of the means of production, in other words, the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. Poverty was rife and there were corresponding idealistic and anomic responses from the oppressed in society.

Robert Owen sought to build a workers’ commune without addressing the cause of inequality and the luddites went after instruments of labour without a clear understanding of the historical dynamics of the period. The Paris Commune of 1871was more decisive as it sought to address the political question of power. Although, the Paris Commune was short-lived, Louis Auguste Blanqui, the leader of that revolution and his comrades provided leadership (Marx, 1977). The working hours’ movement in North America sought to reduce the burden of the workers. In Chicago, the ‘Haymarket Eight’, namely, August Spies, Albert Parsons, Fielden, Michael Schwab, Adolph Fischer, George Engels, Louis Lingg and Oscar Neebe provided a lesson in leadership: they led from the front, not from the rear.

However, the twentieth century witnessed the seizure of state power by the toiling people. The Soviet Union, Communist China and Cuba where the workers held sway are concrete examples. The point being made is that the communist alternative provided the bipolar platform for ideological struggle between capitalism and communism as well as the direction of trade union struggles in the global north and south. While workers and their leaders in the north largely oscillated towards economism, i.e. improvement in the workers’ conditions by means of wage increase and conducive work atmosphere, some in the south wanted to address the power question (Madunagu, 2004), The quest was undermined by the authoritarian post-independence neo-colonial regimes that led the countries.

Advertisement

Of course, they were ideologically aligned along the bipolar divide despite claims of non-alignment. Bipolarity is over. While there is expectation of multi-polarity, a decentered power distribution in the international system, the ‘unipolar moment’ under the leadership of the United States has endured. Equally, liberal internationalism with the tool kits of liberal democracy and neoliberal globalism has hemmed labour within the confines of economism. It is in this context that we examine the place of labour leadership in this prevailing century. First we address the social conditions of the working class in Nigeria today.

THE SOCIAL CONDITION OF THE WORKING CLASS

To focus on the Nigerian condition is to address the social condition of its working people. The Nigerian condition is harrowing. In the last five years, social indicators for the country are negative. According to The World Poverty Clock, Nigeria now has the highest extreme poverty population in the world. The Nigeria Bureau of Statistics put the unemployment rate at 23.1 percent as at September 2018. Children of school age who are out of school is put at about 10.5 million while social utility like motorable roads are not available. Above all, there is lack of energy for domestic consumption and industrial production. Employment as we know provides membership of the working class movement. Even within the limits of neo-colonial economic production, the lack of stability in energy supply has undermined capacity utilization (CU) in the manufacturing sub-sector of the economy. In 1999, CU stood at 32.2 percent (Toyo, 2010) while the current is about 61 percent. This energy reality has led to massive divestment from Nigerian economy and relocation of businesses to neigbouring countries like Ghana, Benin Republic, Ivory Coast among other countries in the sub-region.

Advertisement

Education, an important human development variable is underfunded thereby undermining the drive for human capacity development in terms of research and development. To worsen matters, the country harbours two major terrorist entities such as Boko Haram and ‘Fulani herdsmen’ whose activities have resulted in the death of thousands and a huge population of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). The security profile of the country is a major disincentive for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). It is empirically proven that FDI is the most sensitive thing in globalized capitalist production relations. In specific terms, employer-worker relationship is precarious. The workers in Nigeria are casualized/contracted especially in the manufacturing sub-sector. As at 2002, many companies like PZ industries, WAHUM Group of companies, Asometal Limited, Wempco Group of companies, Veepee Group of companies, Sona Breweries Plc. made effort to regularized their casual staff (Yaqub, 2006). However, this disease still plagues the labour market. As Crouch (2000, p. 71) rightly notes, an increase in the overall level of unemployment weakens the union since it is partly dependent on the conditions in the labour market for its strength.

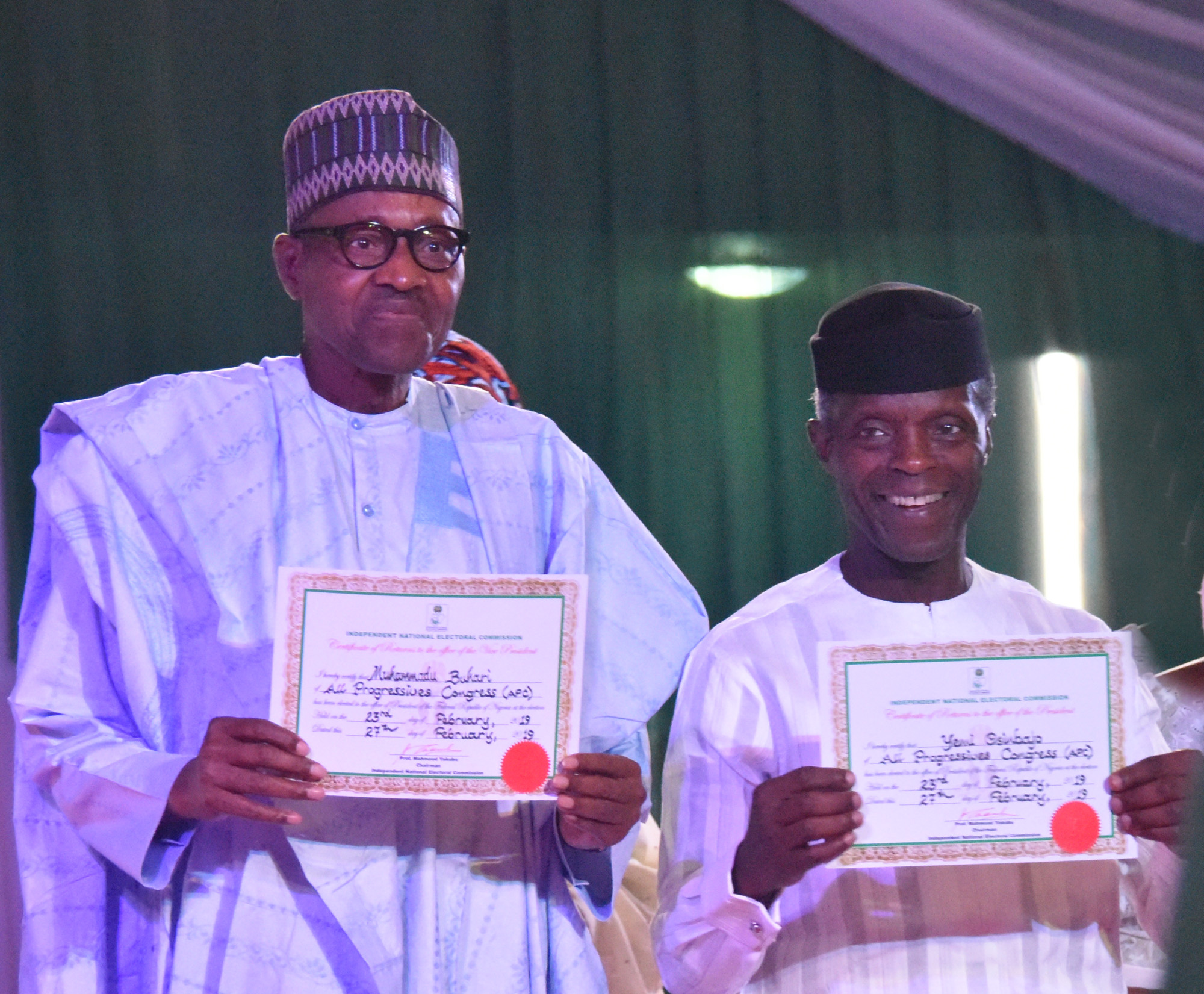

To add to the list of woes of the Nigerian workers, they do not earn a living wage and the new minimum wage of N30,000 though engrossed by the National Assembly is deadlocked at the implementation stage. The plain truth is that N30, 000 is not a living wage with the high cost of living in today’s Nigeria. Even if it is implemented, it remains largely nominal and would be wiped out by post-adjustment policies of massive devaluation of the naira and increment in taxes such as value-added tax, bank charges and sundry fiscal extortions including social costs of school fees and medicare. In what may spell doom for the country, the prevailing administration is taking the country into another debt peonage. Against the background of about $22billion external debt burden, the administration is seeking another $2. 5 billion from the Bretton Wood institutions (BWIs).

Apart from aggravating the already overwhelming social crisis in the country, this will incapacitate the country and undermine its ability to maneuver in the international arena. Even in the midst of this dire need for scarce resources, misappropriation and outright looting of the national resources is an on-going venture for public officials. The future is not looking good. As we can see these issues converge around issues of politics and economy.

THE CHALLENGE OF STATE AND GLOBAL POLITICAL ECONOMY

Advertisement

An understanding of the nature of the Nigerian state as well as the international setting is very important to this conversation because they shape the content and form of trade unionism. Laski (1925) once observed in his Grammar of Politics that men conceived of the state in the context of their own experience. The Nigerian state is a neo-colonial state and its output as an entity is the reproduction of the conditions of oppression internally and internationally. Worse still, it is run by predatory feudal elites who do not pretend about development but fixated on some hegemonic control of the state apparatuses that reproduce underdevelopment in the country. For fifty-nine years on, they have not been able to industrialize the country, instead they are hooked to a mono-product, i.e., the sale of crude oil for survival. The question of diversification of the economy remains a rhetoric a populist trope in political campaigns. Without industrialization, the workers’ movement will remain castrated because as earlier noted the strengthen of the labour movement lies in the workforce. Without it, what you have is a sprawling mass of lumpen proletariat who are disoriented and fatalistic about their miserable existence. This probably accounts for the proliferation of religious houses in the country many of which now occupy warehouses of wound up factories. Let us graft this scenario to the international sphere.

We are in globalized world, where production of goods, services and capital markets are integrated with promises of convergence income disparity. For economic prosperity, it de-emphasizes the role of the state in the national economy and reduces it to that of watchman. Its political underpinning is liberal democracy which allows for periodic elections of political leaders in a multiparty environment. But in substance and in relation to underdeveloped countries like Nigeria, globalization means:

… a more liberal or shorthand name for imperialism, domination, exploitation, marginalization, and the overall reproduction of the injustices, inequalities, and poverty that characterize the relations within and between nations. This line of thought contends that globalization is not about people but about money. People are relevant only to the extent that carry credit cards, checkbooks, cash and huge lines of credit and are ready to spend. Globalization is bound to ruin the environment, commoditize human relations, destroy the welfare basis of society, and consolidate inequalities. It would result in what Aime Cesaire calls the “thingification” of people: reducing human beings into “things” to be exchanged at the market place with profit and nothing but profit as the main consideration (Ihonvbere, 2002, p. 2).

For trade union, globalization and the new phase of productive forces has increased privatization and outsourcing of jobs thereby undermining union density (Murray, 2000). We all can now answer the question posed by Ihonvbere (2002), even though it was rhetoric: How is Globalization doing? Nevertheless, a notable development in the age of globalization is the advancement of productive forces, the means by which humans socially produce and reproduce the necessities of life. The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) drives the new globalization and today the industrial fourth industrial revolution that centres around artificial intelligence (AI) is already in the public domain and a pre-occupation of scientists of all hues. These changes in productive forces affect labour relations in different ways that are either positive or negative. Without doubt, we can see that the real challenge for trade unions inheres in the nature and character of productive forces, the state and international political economy.

WHAT TRADE UNION IS AND IS NOT

Advertisement

Madunagu (2004) was quite clear in his characterization of trade union. For him, trade unions are “economic groupings of the class created for the protection and expansion of workers’ rights under a given slave system”. Madunagu further distinguishes this from a political organization of the working class aimed at capturing political power. Madunagu’s definition fits somewhat the western model and that is what contemporary trade union in Nigeria is and has not gone beyond the western model of economism characterized by a narrow focus on workplace conditions, top-down mode of organization, low membership and commitment to what Fairbrother (2008, p. 213) has called “policies associated with economic instrumentalism and compromise.” This fact has earned labour leaders the sobriquet of ‘labour bureaucrats’. The trade union needs to go beyond economism to exert its social movement essentiality.

This would mean questioning in fundamental terms, labour-capital relations while being locally focused, embedded in the workplace and the community to forge “…a distinctive and transformative union identity…” (Fairbrother, 2008, p. 213) in the context of the triple challenge which we have identified in the productive forces, the state and the international system. It also must cultivate the global attribute of social movement manifest in the conscious understanding of the relationship “between workplace, civil society, the state and global forces in ways that can lead to measures resistance to the deleterious effect of globalization. This new form of struggle being suggested is hardly possible if the ideological deficit in trade unions are not addressed. This deficit is addressed in what follows.

Ideology and class consciousness.

Advertisement

Ideology is defined as “any comprehensive and mutually consistent set of ideas by which a social group makes sense of the world” (McLean, 1996, p. 233). The world view of the working class is material. This approach to making sense of our world is fundamentally dialectical. We understand the society in its dialectical unity and discover the laws of capitalist development and how it leads to the impoverishment of the working class.

This understanding is important and without class consciousness which arises from ‘education for critical consciousness’ based on a materialist world outlook, workers will perceive the reality around them as arising not from the relations of production but a natural order of society. The leadership of the trade union needs to attain class consciousness before they can lead. Class consciousness will enhance an understanding of the totality of material life: the link between our role as workers, economy and politics and the global capitalist system. It is the only way that the union leaders can assume the vanguard role as the most advanced cadres of the working class movement, in other words, transit from being only a class in itself but a class for itself capable of assuming the historical role of changing the social conditions of oppression in society.

Advertisement

CONCLUSION

In the foregoing, we have argued that leadership is very critical to the struggles of the labour movement in the form of trade unions or trade unions as social movement. This submission is historically grounded in the ‘Eight-Hour’ struggle of the workers in North America in which August Spies and his colleagues triumphed while paying the supreme price. It is equally argued that contemporary trade unions in Nigeria are welded to economism, a western model of labour struggle that barely interrogates the structural underpinning of the plight of the working class beyond wage modulation.

Advertisement

Since the 1930s, political organisations of the workers with linkages to the labour movement addressed the power question in Nigeria (Madunagu, 2004). However, despite the limiting factor of global capitalist hegemony, a transition from economism to further social engagement such that that interrogates the labour-capital relations in fundamental terms including the interplay of state and international social forces is imperative. This transition is hardly possible with an ideologically conscious union leadership. It is desirable and meaningful in the light of the shifting dynamics of productive forces on a global scale.

Professor Akhaine delivered this keynote paper at the Trade Union Congress (Lagos Council) Second Annual Workshop Held at Presken Hotel, Ikeja, September 25, 2019.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment