You can read the first part of the Lagos slave factories series HERE.

Vehicles and hasty motorcyclists glided to a halt to allow casual workers, sometimes in their hundreds, to cross to the other end of the road, where they marched at breakneck speed before the clock nipped at 7:30 am. Through the narrow, cage-like entrance, they walked into a bright, expansive compound where the X-pression hair factory was sitting.

Solpia is the registered corporate name of the hair factory, while X-pression is the brand name. According to findings from the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC), Solpia is owned by Kim David Pyung Il and Park Jane Ju Hyun, who are Koreans.

In 2021, the Korean Embassy in Nigeria commended Solpia factory in Lagos for employing more than 7,000 workers for its wig products that are also exported to other countries, including the United States.

Advertisement

Solpia factory in Lagos employs more than 7,000 workers. It's wig products(X-Pression, Naomi & Vicher) are exported to many countries including the USA. GM Shin is working in the wig business for 30 years and contributing greatly to job creation and made in 🇳🇬 export. pic.twitter.com/tO1IDJMxai

— 주나이지리아 대한민국대사관🇰🇷 Korean Embassy in Nigeria (@KorEmbNigeria) June 2, 2021

Advertisement

Machine, boiling, cutting, brushing, and tying are some of the many departmental sections in the hair factory located in the Agege area of Lagos state, where desperate job seekers are taken advantage of by recruiting firms that empty applicants’ pockets despite their glaring beggarly situation.

Three recruiting firms have agents interfacing with applicants at the company’s front door.

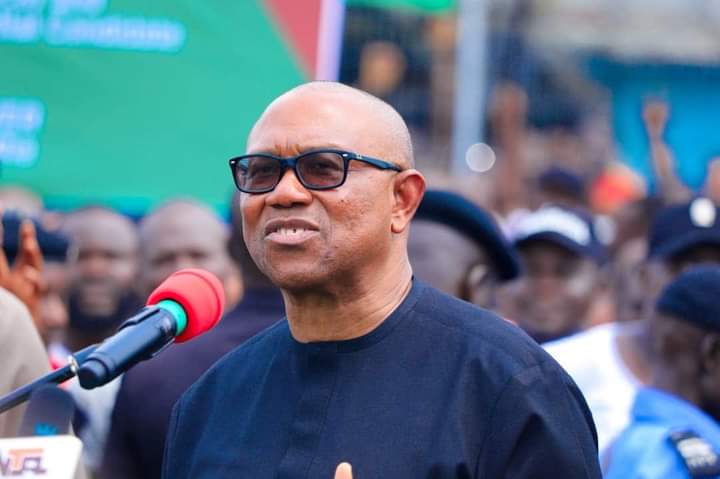

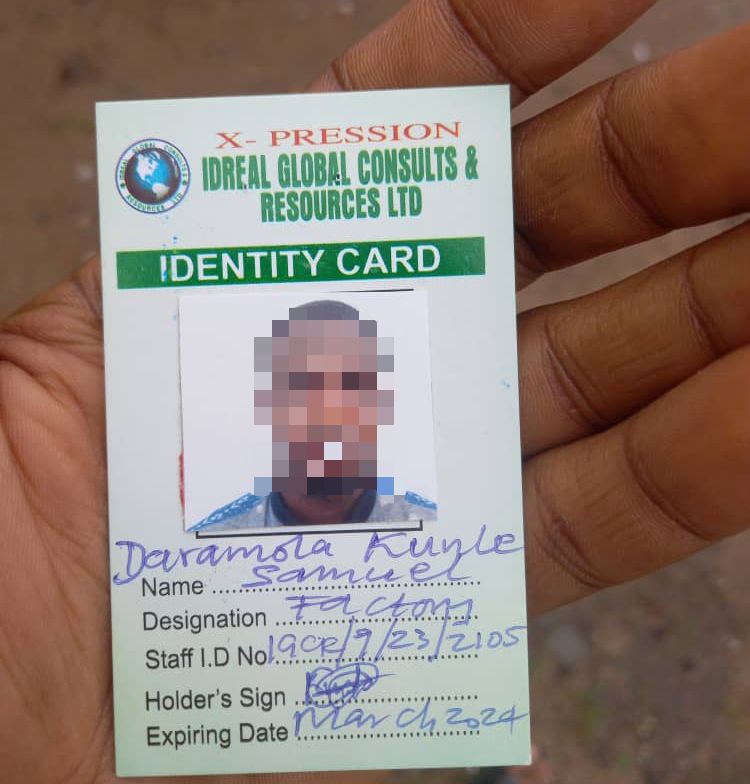

TheCable’s Kunle Daramola was recruited by an agent of Ideal Global Consults & Resources LTD two months after he filled out an employment application form and made a payment of N2,500. Mr Williams, the agent, charges job seekers N4,500 and sometimes as much as N6,500 if an applicant is unable to provide vital documents like a senior secondary school (SSCE) result.

Combing, straightening long strands of hair, and breaking back for eight hours daily for ambitious targets normally would not require an SSCE certificate, but Ideal Consult and X-Pression through Williams still charge for this. If a job seeker is unable to pay the sum, he allows an instalmental payment, with at least N2,500 paid upfront and the remainder deducted from the applicant’s first salary.

Advertisement

The transactional recruitment process, despite happening daily in plain sight at the company’s front gate, is in total contravention of X-Pression’s stance on financial inducement for employment and promotion.

“Solpia Company never request money or gift items for a job interview, staffing, transfers from sections, and confirmation of other allowances and clinic use,” the company’s rule 8, boldly written on the manual shared with new workers, reads.

Alongside this oddity, no employment contract is issued even after workers have spent more than three months in the factory, as mandated by the Labour Act. Casual workers are shown the way out of the factory without notice, forcefully placed on compulsory leave without severance pay, and never to be seen again.

TWO DAYS AT X-PRESSION FACTORY

Advertisement

Welcome, 7:30 a.m. is factory time. N1,600 daily wage and N200 if you calculate per hour of work. The daily target bonus is equal to an additional N200. However, the bonus will not be paid when a worker comes late. Failure to meet the target means forfeiture of the bonus. The closing hour is 4:30 p.m. Working overtime to meet the target is allowed but not rewarded.

After a round of paper examinations, all new workers—almost 30 of us—were put straight to work. Some went to the combing and brushing section, where bunches of hair were methodically drawn through hackles (a nail comb) clamped to workbenches. A workbench has more than twenty hackles arranged on it, leaving less than a yard of space for a worker to throw a bunch into a hackle without obstructing another.

Advertisement

Young men, some with clothes off and armed with appliances, sweating like gladiators at the pit of Rome’s Coliseum, are flanked by women clipping hair to taste, working brand symbols on them, and fitting the products in extra-large bags and buckets waiting to be transported for sales. There are no air conditioners by the way.

The new workers watched senior colleagues like Bishop, a man who looked more like he was in his late 30s, with sunken eyes, pointed brown brows, and determined veins running across his hands, as he pulled a bunch of hair out of the hackle, threw it deep into the legion of nails, and pulled back to himself. He dropped the bunch, smooth and straight, in a big bag beside him. Bishop swiftly picked another bunch and aimed again at the hackle as he was tasked with turning in 260 bunches of straightened hair in an 8-hour shift.

Advertisement

With all types of hair, different measures of length and every sort of style, from Amanda to Bouncy Kinky, Curly and Ceres, new workers joined the hackle parade and within a few hours, their fingertips were already turning faded black with red discolouration. By noon, moulds of blisters had formed at the edges of workers’ hands.

“When your hand folds and it is difficult to open, don’t worry. When you get home, boil some water for a few minutes, then soak your hand in it. It will de-stress and relieve the hand. That is how I have been doing it,” Uzor, another senior colleague, whose target was 160 units of hair per day, advised new workers with blistered hands.

Advertisement

AT NOBLE HAIR FACTORY, HAPPINESS IS ACHIEVED THROUGH HARD WORK

The red banner above is one of the things that would catch your attention immediately after you walk into the sprawling workspace of Noble’s hair, two blocks away from the X-pression factory.

Noble Hair is a brand name for Rebecca Fashions Limited. On the CAC website, the owners of the company was not listed. It only shows “zero persons with significant control”.

I was hired on the spot on June 7 after I sauntered into the factory’s threshold to ask the gatekeeper the official I could speak to about employment. He instantly asked: “Are you ready to work now?” With a nod denoting acceptance, I was instantly thrown into the sport of loosening strands of hair wrapped round metal batons.

From day one, new workers were given targets and were pressured to deliver by learning from their colleagues who used thick embroidery needles to snag off bands from hair wrapped around rods. After this, the hair was forcefully rolled until it separated from the metal rod.

While some work was done in machines where long strands of hair were taken out of extruder machines and dry-cleaned, other work was done in cutting, where sharp equipment like electric bone saw machines was used to slit long hair into different essential sizes.

The workers in charge of the cuttings did this with their bare hands, and only a few wore translucent hand gloves. At the Noble factory, five units of hair were calculated as one target. Experienced workers were tasked with reaching 150 to 200 targets, while new workers were subjected to loosening 30 to 50 targets in a single shift of 8 hours.

Sara, a 25-year-old female casual worker who had worked at both X-Pression and Noble factories, cited low pay and strenuous targets as reasons she left the latter.

“Noble does not have many workers like X-pression. So, the few workers are made to do more than their share of work, more like three workers’ jobs for one person. Noble paid me around N36,000 monthly, and sometimes it was not up to that. While at X-Pression, it was over N40,000 and I heard they have increased it to like N50,000,” she told TheCable a few days after leaving Noble to join its biggest competitor in the Agege area.

Pelumi, another female worker, said: “The first salary I was paid was N30,000. It all depends on your target. I stopped working there last week, and all I can say is that the payment was not good enough.”

Despite the constantly rising cost of living in Nigeria, Noble Hair still pays less than the nation’s minimum wage to some of its casual workers who spoke with this reporter.

NOBLE HAIR SAYS THERE IS SAFETY EQUIPMENT IN THE FACTORY, WORKERS SAY IT DOESN’T EXIST

In an interview with TheCable, a human resources officer at Solpia who simply identified himself as Tope, said the company provides safety equipment for its workers.

“We provide them with aprons, gloves, boots and even chemical wears. The chemicals they work with are not harmful, they are like hair conditioners, so they are not harmful in any way,” Tope said.

“But since the government is asking, we had to provide these gadgets. Workers who work with combs are given hand gloves. Almost all the sections are with one or two protective materials depending on the nature of jobs being done in those sections.”

Following up on Tope’s claim, a worker, who requested anonymity, told TheCable that no form of safety gadget was offered by the company as of November ending.

On extortion by recruitment agencies hired by the company, Tope said: “I will ask about the incident and we will give an official response on that.”

Femi Makanjuola, a lawyer on labour matters, said companies have no excuse for not enforcing safety gadgets on factory workers.

“The law is there to guide both the employers and the employees. An employer cannot put the lives of the workers at risk because they complain of not being comfortable,” Makanjuola told TheCable.

“From my point of view, Nigeria has reasonably good labour laws but a lot of employers do not comply with the laws. Employers usually exploit people with low or no level of education.

“The reality though is that not every employer complies with that provision of the law. Our regulatory authorities that are in charge need to look into that.”

On the issue of casualisation, the lawyer said: “The economic challenge is that there are a lot of workers that are casual. We define casual workers as contract staff, some are daily staff, some are part-time and some with other specifications.

“Section 7 of the Labour Act provides that when you have worked with somebody for three months, the employer should give a contract of employment to the employee.

“On exploitation, any employee can approach the National Industrial Court to demand for his emolument from the employer if they are being withheld.”

Drawing from a historical perspective, in his 1970 book ‘Strategy and Tactics of Nigeria People’s Republic of Nigeria’, the late Obafemi Awolowo, Nigeria’s former federal commissioner of finance, spoke about his aversion to casual or daily paid labour.

He argued with five strong reasons why casual labour should be jettisoned under any economic system, whether it is socialism or capitalism, due to the “terrible and destructive psychological assault on the self-respect and human dignity of those employed under the system.”

He was not alone in the rejection of the laborious system. The National Industrial Court of Nigeria described contract staffing as a purely economic decision.

“The practice is largely motivated by economic considerations of profit, cost control, economies of scale, and comparative advantage rather than any human resource theory. The drive for global competitiveness and business survival has promoted and popularised it as a business model, [that] significantly reduces an organisation’s operating overhead costs,” NIC said in a 2014 publication.

Though the Nigerian Labour Act does not provide for casual workers, nor does it provide a legal framework for the regulation of the terms and conditions of casual workers, the act, in section 7(1) still provides that a worker should not be employed for more than three months without the formal recognition of such employment.

In a legal opinion by Chibuzo Ofoha, a Nigerian labour lawyer, he raised concerns about “companies that have developed sharp means to undermine this provision by employing casual workers for three months and then dismissing them.”

However, it seems the exploitation of casual workers by companies is prevalent due to regulatory oversight.

Since passing the second reading in March 2020, the bill seeking to criminalise casualisation of workers by employers in Nigeria after six months of engaging them has failed to move forward, if not yet buried, by the house of representatives.

Add a comment