With less than two months to go, concerns by the opposition that next year’s general elections would not be free and fair, appear to be getting louder by the day. The voice of the main opposition Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) has, so far, dominated the complaints.

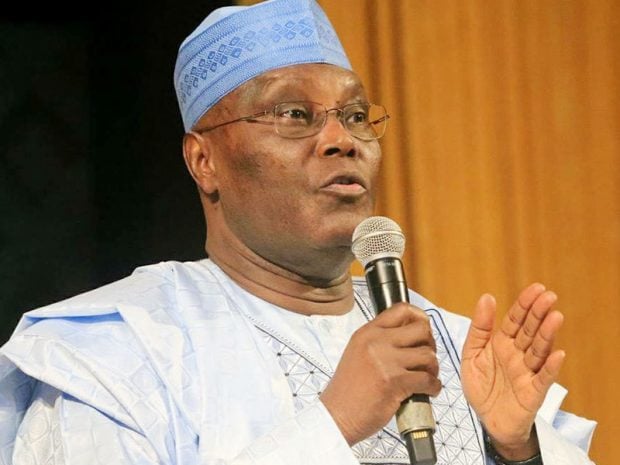

At the belated signing of the Peace Accord, for example, PDP presidential candidate, Atiku Abubakar, was quite vocal on his fear that the election would be rigged.

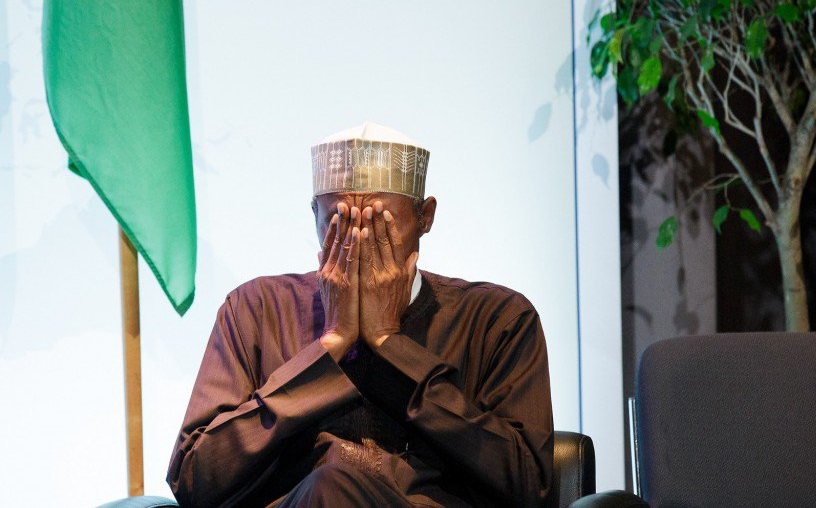

The suspicions are based on a number of factors, the latest of which is President Muhammadu Buhari’s refusal to sign the Electoral Amendment Bill. Those who peddle this as the strongest and clearest sign yet of rigging, argue that there are, at least, two major elements in the bill that would have made rigging more difficult: electronic collation and transmission of results.

If Buhari is really serious about free and fair election, as he has said repeatedly, why has he refused to sign the bill that would only make the process more transparent?

Advertisement

Others are worried about something else – the fear of militarization on election day. Those who doubt the role that state power can play to influence the outcome of an election, or need a Master Class on the subject, can ask the PDP what the party did in Ekiti in 2014. The whole range of state power – from soldiers to armed policemen and from department of state services to party hacks – was deployed in their numbers, with massive cash backing flown in from Abuja by chartered planes.

Security officials outnumbered voters on a scale not matched by APC’s retaliation in this year’s governorship election in the same state. The overwhelming presence of security agencies was, at the end of the day, perhaps the single most potent decider of the outcome of the 2015 governorship election.

Politicians know the potency of state power and the only time they are not complaining about its misuse is when they’re the ones using it.

Advertisement

But there are softer issues as well: allegations that INEC and the APC are in cahoots to create additional polling units in Niger and Chad to favour the ruling party; claims that there are ranking Buhari sympathisers in INEC; and also, that the commission is being maliciously underfunded by the executive.

Also thrown in the mix when Buhari was the most visible northern, Fulani candidate in the race, was the criticism by the PDP that at no other time in the recent memory of electoral contest has there been a case when one of the leading contenders and the main electoral umpire were both from the same ethnic group. Like chaff driven by the wind, this argument vanished after Atiku emerged.

It would be uncharitable to dismiss all the complaints out of hand. But as I said in this column last week, exaggeration is the commonest strain of fever at election time, and politicians everywhere have extraordinary talent for crying wolf where they sense failure.

Before his election, for example, President Donald Trump, the peerless wolf-crier, said repeatedly that Hilary Clinton had ensured that “the system was rigged” against him. It was his rallying cry to his base throughout. When he won, however, and it came to light that there was credible evidence of Russian meddling in his favour, he cried “witch hunt”, insisting to date, that he had won fair and square.

Advertisement

If Atiku seriously believes that next year’s election would be rigged, and he has evidence for his claim, the Peace Accord where he and his main rival, Buhari, were scheduled to meet face-to-face, would have been a good place and time to confront this demon. Yet, I imagine that speaking up would not have been an easy task for the former Vice President whose party, the PDP, so notoriously rigged the 2007 election that even the beneficiary felt ashamed.

Had Atiku taken his first chance to sign the accord instead of hiding and misleading the public that he was not invited, he would have put the matter out there and kept his gunpowder dry for another day.

Presidential non-assent to the amendment bill should not be his biggest headache. It should also concern him that even in countries where full electronic collation and transmission of results is in play, the human factor – not to mention the growing cottage industry of underworld hackers – is still a major problem.

Is the Wazirin Adamawa aware of concerns in the public domain that a top member of his party recently visited Russia’s hacking underworld? Was that for window-shopping or what?

Advertisement

At any rate, all parties appear to agree on the need for the use of full biometrics and the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has also promised to discard the use of “incident forms” and upgrade its service. Why the obsession on a point in the bill (transmission, transmission, err, transmission!) that has not even been subjected to limited test of season?

My sense is that our elections have continued to improve, and we must maintain the pressure and momentum. But it would be ridiculous to pretend that INEC has been sitting on its hands, waiting for orders from the Villa to dispense results.

Advertisement

From the time in 2015 when 80 election results were nullified by the courts we have moved to the point where only three court-ordered cancellations out of 178 conducted occurred as at February this year.

If, all said and done, the PDP has the majority in the National Assembly, which it claims to enjoy, and the party believes that next year’s election is doomed without the passage of the bill, its members may just as well use their majority advantage to override the President’s veto, instead of wasting time calling for a parliamentary system of government, which they know will not happen.

Advertisement

Of course, there are subtler aspects of the concerns about free and fair elections not contained in the laundry list of the big parties: access to public spaces and platforms for engagement. The outcry by the smaller parties about being frozen out of the debates, for example, is a valid concern, especially if the threshold for inclusion, if there was any, was not publicly known beforehand.

The parties may argue, justifiably, that shutting them out from public debates denies them fair hearing and skews the field against them, even before the contest has formally started. Yet, the blame should be placed where it belongs: the doorsteps of the organisers, who must take steps to redress the situation.

Advertisement

As for the other matters of concern, including INEC’s purported underfunding, claims of gerrymandering and possible militarization, these are familiar scarecrows from the past. The way to tackle them is not to purchase public sympathy by crying wolf, but to provide evidence and shine the light.

The PDP may well have reasons to be afraid of tasting its own medicine, which it administered on others for the better part of 16 years. But it should rest assured that voters understand that it is in their own best interest that elections should be free, fair and credible.

That conviction, however imperfect, was the weapon that dislodged the PDP from power and voters and civil society are not about to give it up. Politicians should face their campaign and leave the wolves in the woods where they belong.

Ishiekwene is the managing director/editor-in-chief of The Interview and member of the board of the Global Editors Network

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment