I was numbed by the numbers by the time I finished my extrapolation of the statistics.

The criminal ugliness that happened in our country in recent months is something that should make this government nervous about its future with the people.

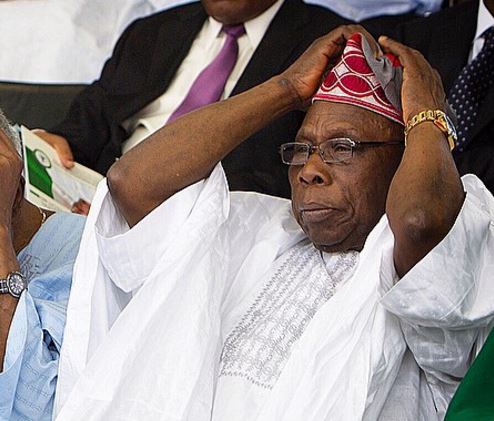

Clearly, President Muhammadu Buhari’s inability to keep a simple promise of internal security could make him fall out of favour completely.

Buhari’s inaugural speech speaks directly to the issue: “Boko Haram is not only the security issue bedeviling our country. The spate of kidnappings, armed robberies, herdsmen/farmers clashes, cattle rustlings all help to add to the general air of insecurity in our land,” he said in May last year.

Advertisement

But with two and half years down the line, Buhari’s change plan for internal security and economy appears to give no serious solution.

My focus here is not on the war against Boko Haram, but everyday crime in our cities and suburbs.

From a Methodist priest kidnapped on his farm in Ibadan, Oyo State, by some young people between the ages of 18 and 24 to the former Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Amb. Bagudu Hirse, who had his day with Kaduna kidnappers, it is every minute a crime in rural and urban areas across the country.

Advertisement

It’s not clear what the total figure on the surge in criminal activities will look like, but from their own testimony that the police lost 128 officers to ambush and face-to-face fight with “bigots” and “militants” in just three months, we can imagine how horrible the situation is for our internal security.

The argument is straightforward: with a disastrous economy and ineffective policing there must be uptick in crime wave.

Yes, we don’t have to believe every motivational theory that formed whenever a criminal makes confession using such phrase as “lack pushed me into it.”

But associations between crime and economic factors are best examined at the level of the smallest possible geographic unit.

Advertisement

One examination is to look at the spate of kidnapping in our neighbourhoods from city to city and from community to community. It is high-rise.

Sadly when you combine economic and security failure together, then it is time to sing the nursery rhythm, “there’s fire on the mountain…”

Well, the government apologists will deny there’s problem with our internal security, though they are hurting in silence.

As expected criminologists, sociologists and other researchers may lock themselves in an epic battle over whether recession breeds crime or not

Advertisement

To find out, I turned to United Nations on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

Based on a UNODC report that used police-recorded crime data for the crimes of intentional homicide, robbery and motor vehicle theft, from fifteen country or city contexts across the world with analysis that examined in particular the period of global financial crisis in 2008/2009, there’s a window into why crime is persistent in our country in recent time.

Advertisement

“Where the financial crisis is manifested through decreased or negative economic growth and widespread unemployment, large numbers of individuals may suffer severe, and perhaps sudden, reductions in income. This, in turn, has the potential to cause an increase in the proportion of the population with an (arguably) higher motivation to identify illicit solutions to their immediate problems. Whilst this may appear as a simple explanation for property crime, stress situations are also the cause of many violent crimes. Unemployed persons may become increasingly intolerant and aggressive, especially in their families. Violence among strangers may also increase in situations in which people do not have clear prospects for their future. Whilst unemployment figures are often used as a key indicator for analysis of the effect of economic conditions on crime, official unemployment figures alone cannot provide a complete indicator of either the financial crisis itself or levels of population financial stress. They do not always take account, for example, of those employed in the informal sector, those supporting large or extended families through low-paid formal employment, or those who survive on remittances from workers abroad. Moreover, in addition to loss of employment, the financial crisis may also manifest itself through reduced government social expenditure, increased cost of basic consumer goods, and restrictions on local credit availability. Any or all of these may result in financial stress for individuals and communities, with no change in official unemployment figures,” a part of the UNODC report said.

I really don’t want to exacerbate an already bad situation with this justification. At the same time, I’m careful not be caught in the web of figures that will not make sense in the end, but I want this government to get the picture that Nigerians may be heading for another ‘enough-is-enough’ protests that will be birthed not by a particular organization but by individuals who are truly tired.

Advertisement

Anger and despair are two important ingredients for uprising. I know that the theory of grievance, greed and opportunity structure exist, but that is applicable to Niger Delta and Boko Haram insurgency, where militants take the opportunity of the swamp in the Delta area and the hills and caves in the northeast to fight the government. So the government may decide to ignore the warning.

But without swamp and hills, we can’t forget too quickly that mutiny against President Goodluck Jonathan started with street protests over an “offence” as simple as subsidy removal, though his approval rating was still somewhere in the middle at the time.

Advertisement

In 2011, Tunisia witnessed the revolt of the hungry that started with a single man called Mohammed Bouazzi. Without job as a graduate Bouazzi was doing all he could to fend for himself by selling fruits and vegetables in a cart. That cart was taken away by police and Bouazzi set himself ablaze in protest. That was the spark. Lack of basic necessity such as food pushed people to the street to chorus: “we want bread and water, no Ben Ali.”

After a few days of the protests, Tunisian President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali, who had spent 23 years as the country leader was gone.

It may be hard to accept for this government, but if by the first quarter of 2017, there’s no real change in terms of the way people live (economically and security wise), there may be furious protests that will change the government itself.

It will be the start of a long war with the people that I believe Buhari is least prepared for.

And I think the university teachers and medical doctors are already positioning themselves for such a time.

My final word: Buhari needs to act speedily on internal security. Fear and hunger are two things that can push people to revolt.

Follow me on Twitter: @adeolaakinremi1

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment