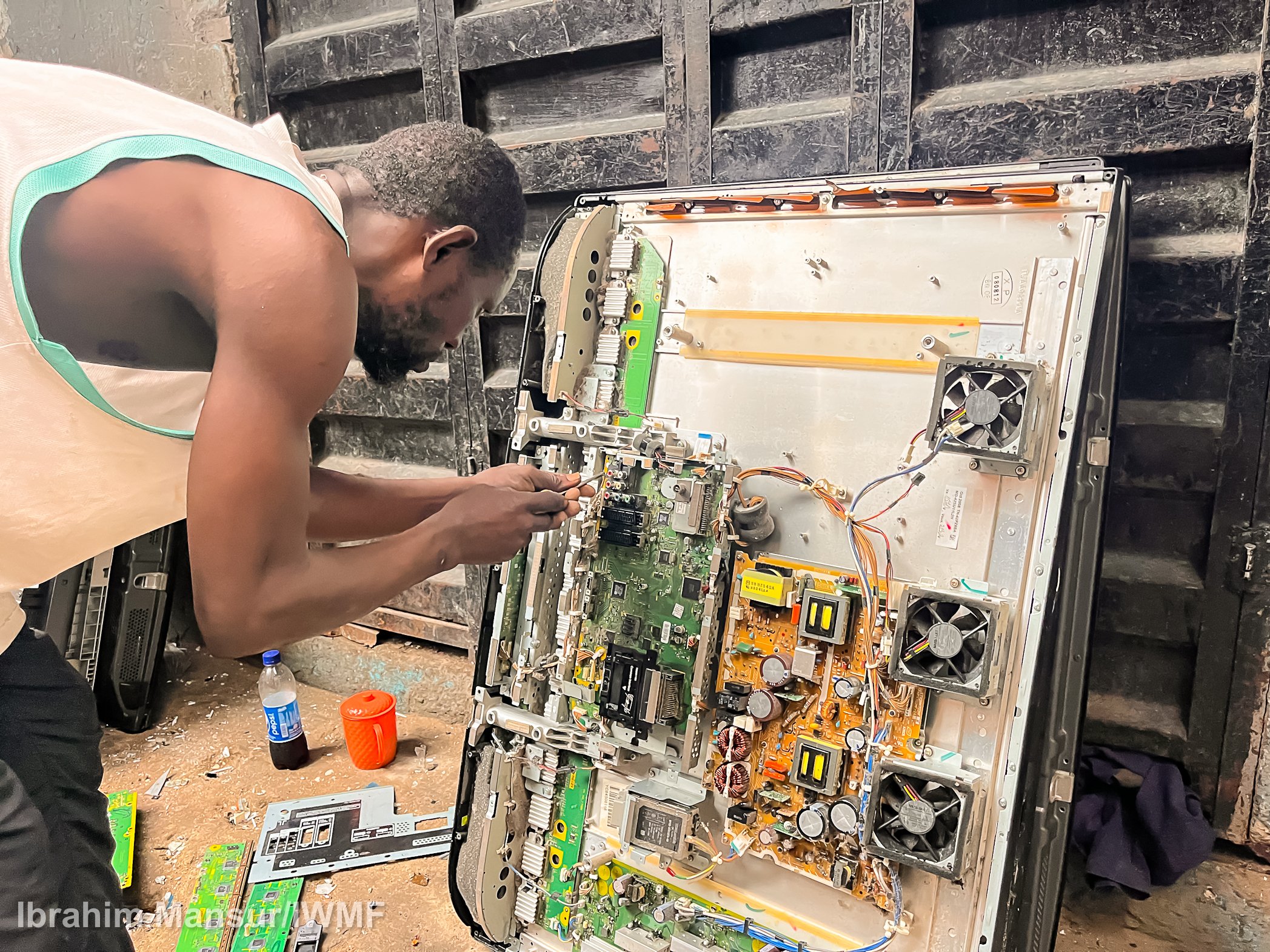

A recycler sorting some e-waste at a scrap yard in Ojota, Lagos state, Nigeria

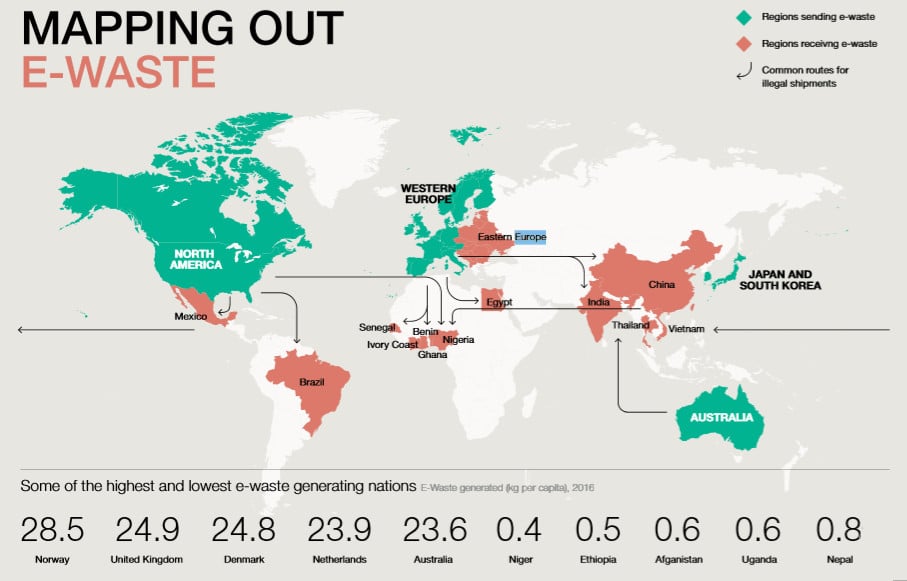

Nigeria has become a dumping ground for electronic waste (e-waste) from developed countries due to its booming market for fairly-used electrical and electronic equipment. The country’s inadequate waste management infrastructure has exacerbated this crisis; hence, the informal sector handles the majority of e-waste disposal, collection, and recycling. This often involves crude and hazardous methods, which pose severe risks to both human health and the environment.

TheCable’s JEMILAT NASIRU AND IBRAHIM MANSUR visited Lagos and Kano states to document the impact of e-waste on the lives of Nigerians. Their findings show a critical economic sector that is destroying the existence of the people while the government looks away.

You could perceive it just as you could see it from a distance — the huge monument of a people’s consumption habits. Upon closer inspection, what appears to be a three-storey mansion is a landfill overflowing with rotten newspapers, clothes, liquor bottles, and everything else dumped there the previous day — and that exactly is the problem. Unsorted.

Atop Olusosun, one of Africa’s largest dumpsites, and Solous 3 landfill, thousands of waste pickers with little to no personal protective equipment (PPE) immerse their bare hands and feet in the trash, sorting through to obtain what they see as valuables – plastics, cans, metals, and sometimes, luckily, misplaced diamonds or gold jewellery. These dumpsites, located respectively at the Ojota and Igando axes of Lagos state, receive much of the city’s daily 13,000 waste deposits.

Advertisement

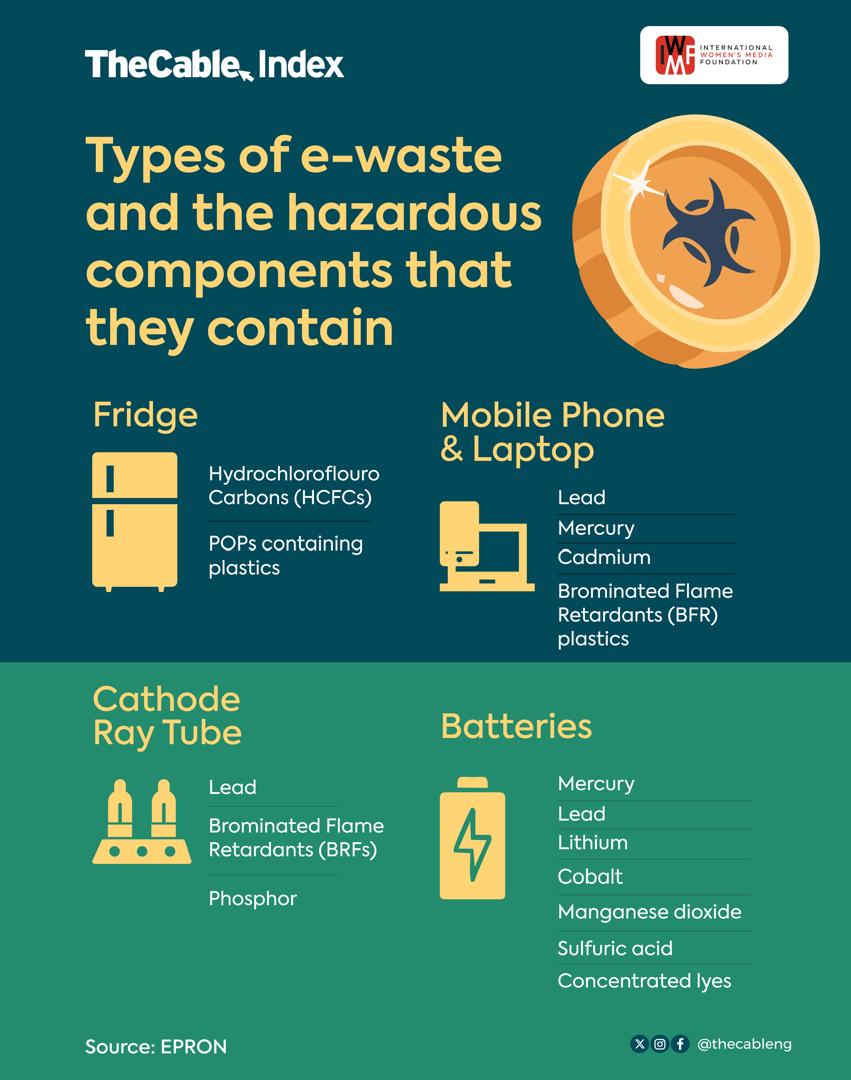

But this towering heap of trash is no ordinary pile of garbage; beyond being an eyesore, it is a teeming ecosystem of waste, and among its occupants are tonnes of discarded electronic appliances or parts (electronic waste or e-waste) arbitrarily tossed away. A chaotic embrace of wires, chipped monitors, and a swollen phone battery — the discarded remnants of our technological thirst — all baking alongside decomposing organic matter under the relentless sun. This compound mixture stews out potent chemical cocktails with ingredients such as lead, cadmium, mercury, zinc, and lithium, silently seeping into the earth and polluting the land and water of host communities.

The air is also not spared. Mostly under the cover of darkness, it is thickened with acrid fumes from the unholy alliance of decomposing and burning waste, a practice scavengers and informal recyclers resort to in an attempt to extract valuable metals from e-waste. The landfills are both workplaces and homes for about 5,000 scavengers. Many workers here live in makeshift apartments built from and on dirt. Their prolonged exposure significantly increases their health risks.

NIGERIA’S E-WASTE ECONOMY

Advertisement

Nigeria has a hunger for fairly-used appliances and gadgets. This craving is typically not intentional, but with a population of 133 million multidimensionally poor people, most Nigerians often resort to used items, some imported. Used clothes, usually called okrika or bend-down-select, used cars, popularly known as tokunbo, and other items come into the country regularly from China, the US, and Europe. Used electrical and electronic equipment (UEEE) that comes at relatively lower prices is sometimes prided by marketers and local technicians as more durable and reliable than brand-new ones.

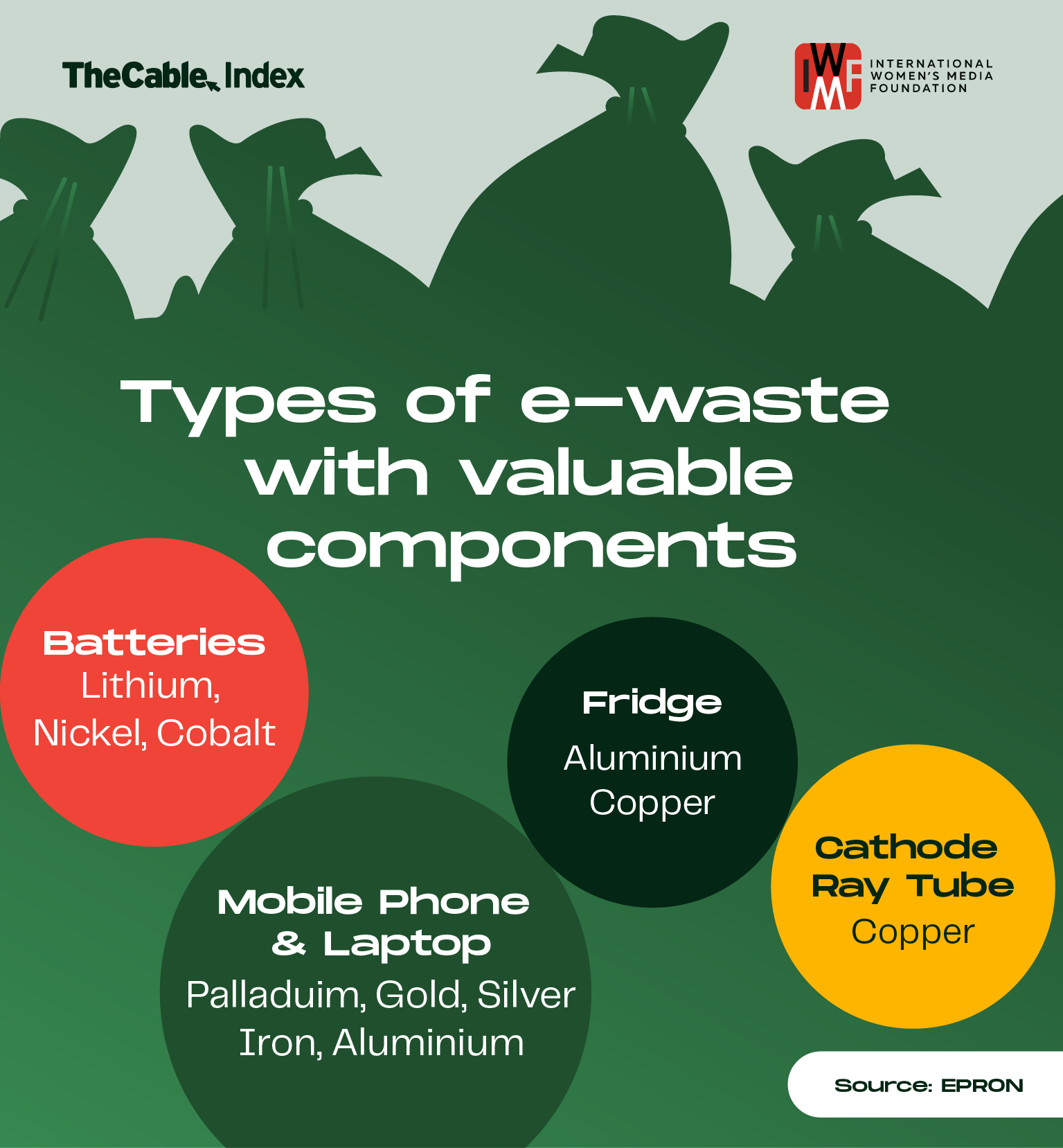

Annually, half a million metric tons of UEEE arrive in Nigeria mainly through the ports in Lagos, but a larger part of these shipments arrive dead. The shorter life spans of these second-hand electronics mean they become disposable quickly, and together with imported e-waste, end up in dumpsites, landfills, or informal scrapyards where they are mined to recover valuable elements and metals like copper, iron, aluminium, nickel, silicon, platinum, cobalt, and gold from scrambled waste.

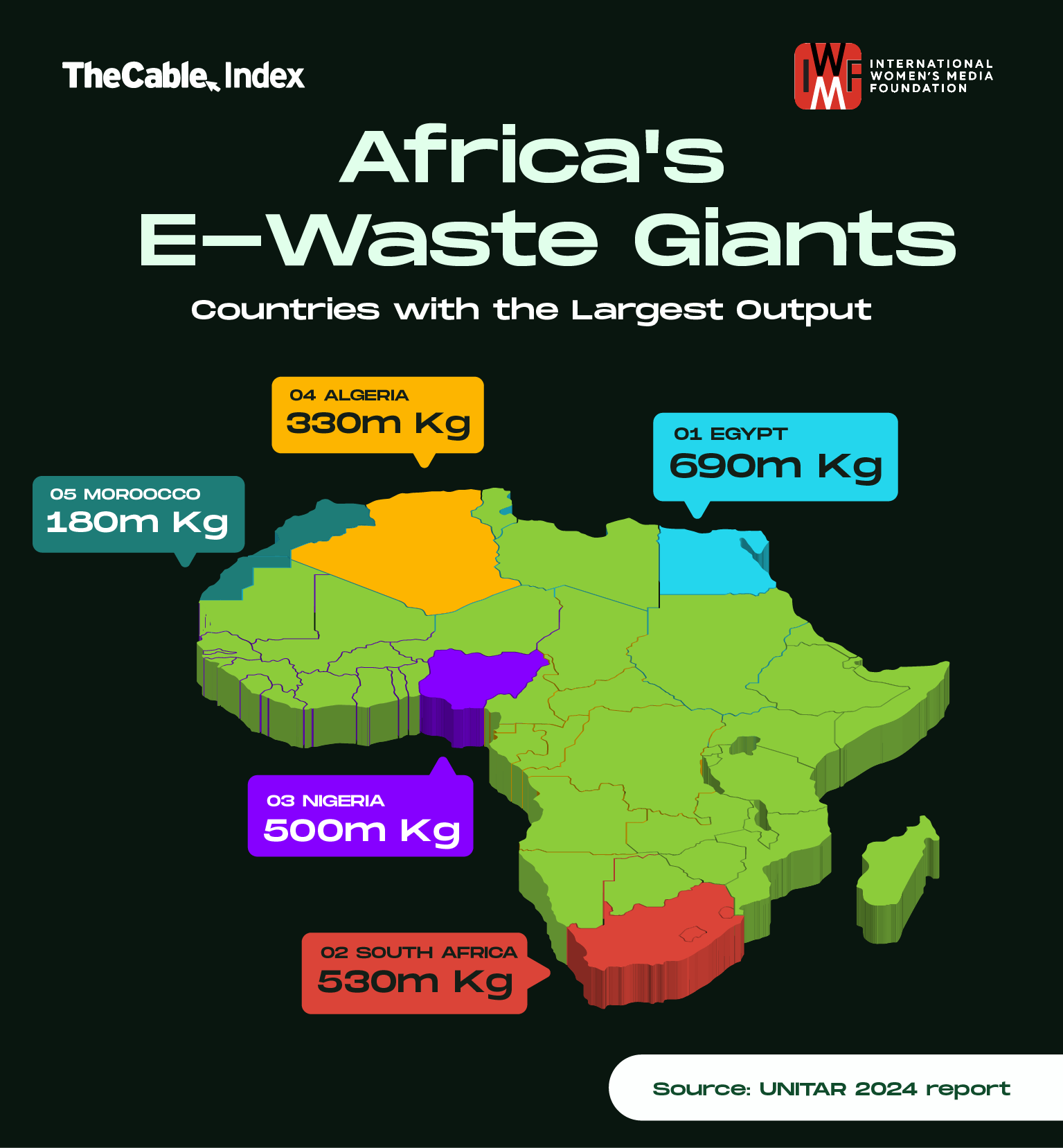

According to the UN’s fourth Global E-waste Monitor (GEM), Nigeria generated (local and imported) 500,000 metric tons of e-waste in 2022. This is the highest in West Africa and the third highest in Africa, after Egypt and South Africa.

Advertisement

Computer Village, the bustling hub of West Africa’s ICT market, is a thriving centre for the sale and repair of new and used electronic devices, including imported items like air conditioners, refrigerators, LCD TVs, telephones and computers. The hub generates a significant amount of waste. The lack of a formal, organised e-waste collection system has led to the reliance on informal recyclers who offer door-to-door collection services, providing a convenient solution for both consumers and businesses seeking to dispose of their old electronics or their parts.

E-WASTE POISONING: THOUSANDS OF NIGERIANS ‘LIVING ON BORROWED TIME’

The United Nations defines e-waste as any discarded product with a battery or plug and features toxic and hazardous substances, such as mercury, that can pose severe risks to human and environmental health. Some of the toxic materials found in e-waste are listed in the ten chemicals of public health concern.

Studies have linked exposure to these pollutants with increased rates of birth defects, miscarriages, DNA damage, weakened immune systems, learning disabilities, and cancer. When e-waste is dumped in landfills, toxic chemicals leach into the soil and contaminate groundwater. When used for drinking, cooking, and irrigation, this contaminated water leads to various health problems for exposed populations. Electronic components often contain microplastics that can enter the food chain through contaminated water. Furthermore, open incineration of e-waste releases greenhouse gases, exacerbating Nigeria’s climate challenges.

Advertisement

Nigeria’s informal e-waste recycling sector, employing over 100,000 people according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), is often characterised by unsafe practices. Mostly unaware of the dangers, workers, including women and children who are termed particularly susceptible to adverse health outcomes by the World Health Organisation (WHO), burn wires, crush cathode ray tubes (CRT) and other mercury-containing devices, putting their health and lives on the thin line of survival.

Advertisement

At Ojota’s “Waste to Wealth” scrapyard, Abdullahi Soja, a native of Kano state who relocated to Lagos in pursuit of economic opportunities, oversees a team of over 100 workers. Starting as a scrap picker in 1992, Soja ascended to the position of CEO of Zion Metals Limited and serves as a board member of the National Association of Scrap and Waste Dealers Employers of Nigeria (NASWDEN). Soja believes his business provides a lucrative livelihood and plays a vital role in keeping young men out of criminal activities.

“Then, I’d use a hammer to cut and break compressors. You see all these marks on my body; it’s from the iron and chisel I used to break compressors,” Soja said, spreading out his hands.

Advertisement

“I have done surgical operations on the marks, but some cannot be removed.”

To improve the working conditions of his boys, a privilege he did not enjoy, Soja said, “We give the boys hand gloves, and they cannot just jump into the work. They must be trained.”

Advertisement

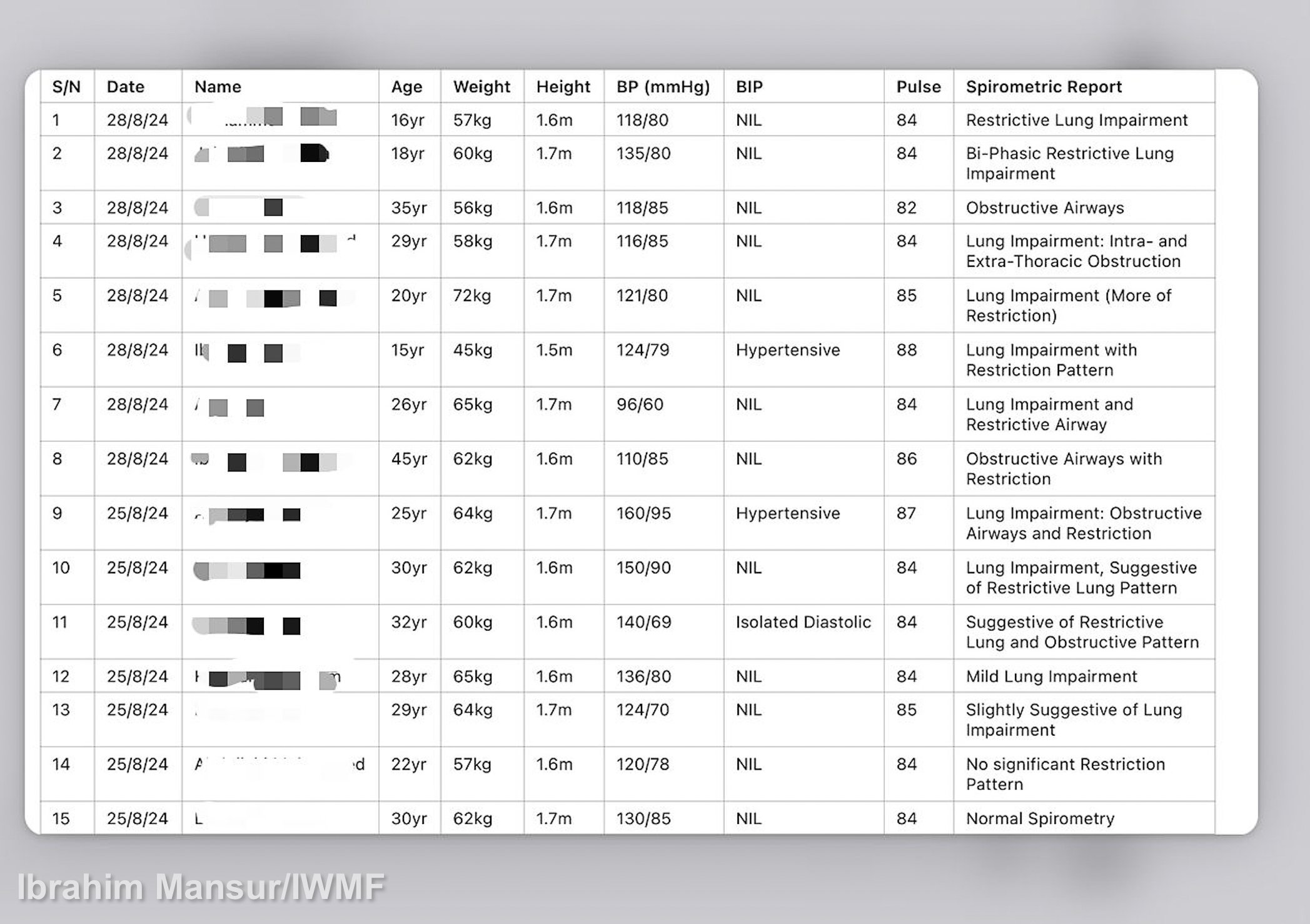

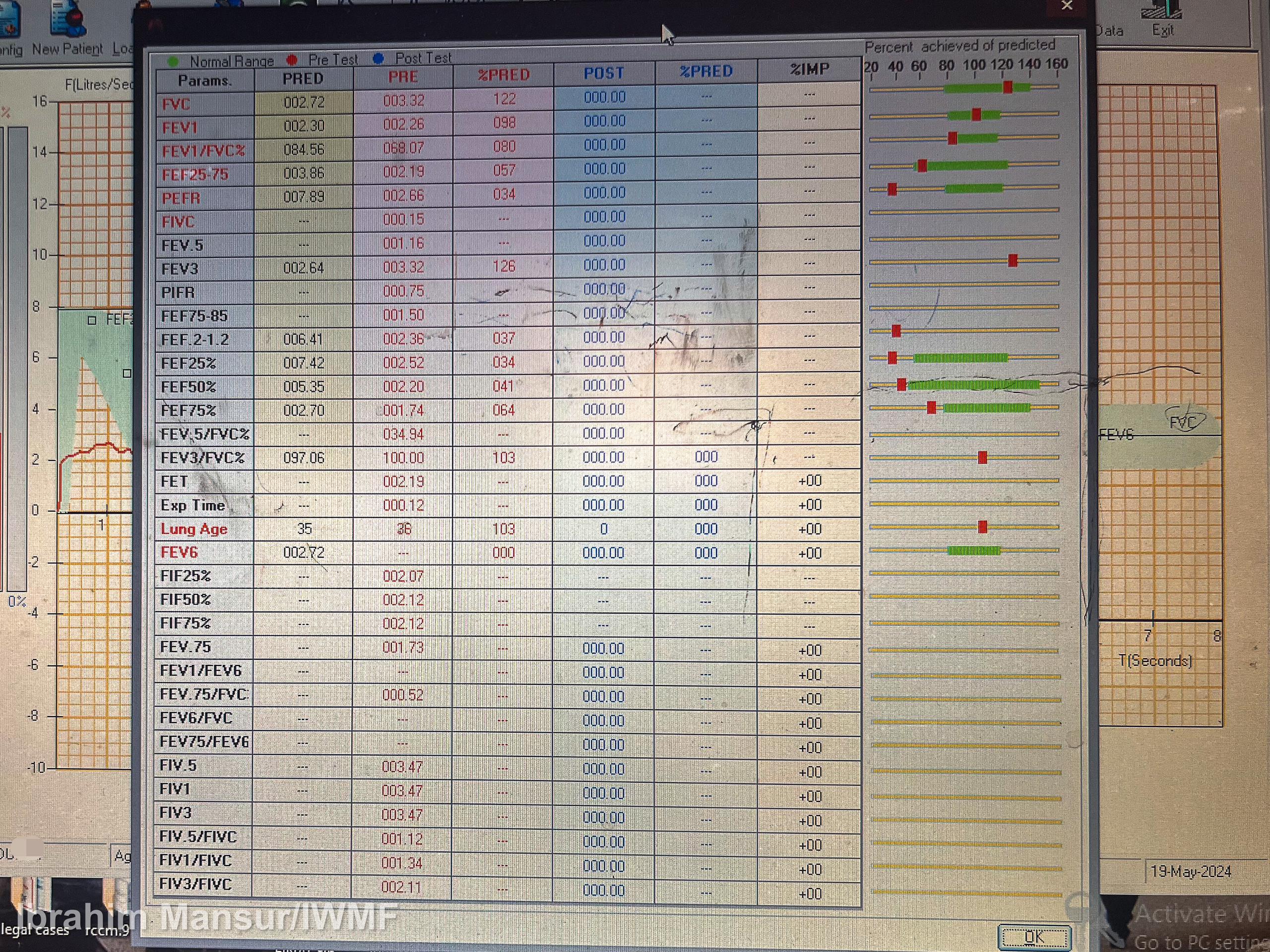

Informal workers in dumpsites who spoke with TheCable complained of body aches, chest pain, fever, persistent cough and headache, and blurred vision. Medical tests (spirometry) carried out on some workers who have been in the business for an average of three years showed impaired lung functions and high blood pressure. These, experts say, may be precursors to even more life-threatening diseases.

Bare-chested, Kabiru, one of Soja’s boys, wielded a hammer, demonstrating impressive strength as he dismantled metal wastes with powerful blows. Despite his slender physique, his strikes, attributable to his 20-year recycling experience, were forceful enough to reduce metal taps to pieces in just three hits. Kabiru and his colleagues sometimes get injured in the process.

“This kind of work is not for everyone,” he said. “But Allah is protecting us. We use plaster to cover our wounds when we get injured while working.”

“We don’t get tired unless it’s over for the day. Even at midnight, we work. I’ve never been to any hospitals, but I do take drugs when I feel somehow.”

Ifeanyichukwu Kingsley Mabuabu, president of the Association of Vendors of Used Computer and Allied Products (AVUCAP) and accredited e-waste collector, who has been in the business for 20 years, said his colleagues are dying – unaware of what is claiming their lives.

“In the past two months, I lost a friend who is into this business. He came to work on Monday and as he was standing, he fell off. We took him to the general hospital, and two days later, he was gone. You see, we don’t care; if it’s a developed country, they would have done an autopsy to know exactly what killed this man. I have lost about three people like that since I started this business. So, the work we are doing, we’re just playing with our lives,” Mabuabu said.

Commenting on the public health implications of indiscriminate e-waste disposal and recycling, Olusola Adeyelu, a physician specialised in pulmonology and critical care, said the practice is a ticking time bomb.

“All the people on the dumpsite and those staying approximately 500 metres away are living on borrowed time. Nobody recycles waste this way again,” Adeyelu said.

“The people working in those places, their generation is already mutated in the sense that they are going to bear children who are not of their lineage because their genetic coding has been altered.

“In years, they will come down with cancer, stroke, and eye problems. Even some of the waste you dump in your house can give you the same problems if you get repeatedly exposed.

“What is going on in their body is hell. From the spirometry result, some of them have both intrathoracic and extrathoracic fixed, and some of them have variable. Some of them are behaving asthmatic already, even though they don’t have asthma.”

A water quality analytical report of a sample of Igando landfill leachate showed high concentrations of cadmium, lead, iron, chloride and ammonia beyond NESREA limits, and residents complained that their borehole water had become coloured and unsafe.

BUSINESS IS THE SAME IN KANO

Farm Centre, Kano’s version of Lagos’ Computer Village, is populated with many stalls stacked with old, non-functional phones and laptops that serve as replacement parts for faulty gadgets. Bilal Yushau Adam, who runs one such stall, said he pays his workers above the N70,000 national minimum wage, placing the scrap business as more financially rewarding than paid government employment. He has a diploma in law but abandoned the certificate for scrap business when he graduated in 2003.

Adam acknowledged the health risks associated with the e-waste business but claimed to have developed “expertise and techniques” to mitigate them. He emphasised that a recycler’s exposure to danger depends on their knowledge of specific devices, citing an example of a colleague who lost his eyesight due to a battery explosion while attempting to extract it from a damaged smartphone.

Showcasing his technical skills, Adam demonstrated how to carefully remove the screen of a smartphone using a razor blade and an unlabeled transparent liquid in a pet bottle.

“Anything related to chemicals has side effects, but we try to protect ourselves,” Adam said.

Children are typically involved in e-waste recycling activities in Kano, mainly as pickers and breakers.

POOR REGULATORY ENFORCEMENT FUELLING INFORMAL E-WASTE RECYCLING

Nigeria has ratified the Basel Convention, which stipulates that only operational electronic waste intended for reuse can be shipped internationally. The country’s National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) is primarily responsible for ensuring environmentally sound practices that align with Nigeria’s circular economy plans. NESREA’s responsibilities include regulating e-waste, both domestically generated and imported.

Ideally, every imported item is meant to undergo inspection to ascertain its functionality and prevent the importing of e-waste, but regulatory shortcomings, negligence, corruption, and infrastructural and manpower gaps create room for a largely unhindered inflow of e-waste.

According to the UN’s GEM report of 2024, Lagos’ Apapa and Tincan Island ports have been identified as major entry points for UEEE, implying that e-waste shipments continue to bypass the Basel and Bamako Conventions. The report added that in 2015/2016, around 71,000 tonnes of UEEE were imported into Nigeria through these ports, and that around 69 percent of these shipments were stuffed in cars, buses, and trucks imported via roll-on/roll-off mode to evade inspection. TRT World reported that 500 thousand containers of e-waste enter Nigeria every month.

The EE Sector Regulations Act 2022 allows the importation of UEEE but prohibits the importation of e-waste. It provides that the principles of the regulations shall be anchored on the 5Rs — reduce, repair, reuse, recover and recycle — as the primary drivers of the sector. Despite efforts to implement the extended producer responsibility (EPR) and producer take-back, challenges related to enforcement, awareness, and funding have persisted.

Among its provisions, the regulation prohibits the open burning or disposal of e-waste at landfills or dumpsites. End-users are also mandated to separate e-waste from other waste streams and return it to collection centres. However, enforcement is weak. There are limited collection points, and people often rely on informal collectors who provide door-to-door services, even if less regulated.

Collectors are also prohibited from storing e-waste for more than six months, but Mabuabu said appliances in his shop have been there for over a year. “NESREA doesn’t have enough workers,” he said.

According to this 2019 report, a NESREA spokesperson “admitted” that the agency is unable to fully enforce its regulations governing e-waste imports into Nigeria.

DESPITE RISKS, E-WASTE RECYCLING IS A MULTI-MILLION DOLLAR BUSINESS

“With safe recycling, there’s 100 times more gold in a tonne of e-waste than in a tonne of gold ore” — UNEP

E-waste is a double-edged sword. While it poses environmental and human health threats, with a safe and efficient recycling industry, it has huge economic benefits.

In Alaba Rago, the second biggest electronics market in Lagos, Yusuf dismantled an LED television set nut after nut. He said the imported TV sets fetch more money when dismantled and the parts sold separately than when sold off whole.

In 2019, Nigeria generated ₦64.2 billion worth of electronic waste, ranking second in Africa after Egypt.

While Nigeria pays the price for the crude recycling of e-waste, most of the valuable materials extracted from discarded electronics are often exported, leaving behind a toxic legacy. Informal recyclers often sell their merchandise to Chinese, Indian and Lebanese dealers.

Adam said he gets used phones from China and, after recycling, exports the recoverables back to the Asian country.

“We get the market from people, and we get them from China, and from those that deal with new phones. We sell phone engines, batteries, and charging ports. You get whatever you want here, and we do recycling to ship some scraps back to China,” Adam said.

Scavengers have also become the unexpected heroes of Nigeria’s e-waste market. Their competitive pricing has lured consumers away from formal recycling channels.

“The e-waste management companies are not forthcoming and Eterra is not going to buy at the current price. I will sell this computer for N13,000, and these abokis (scavengers) will buy it at that price. If I call the e-waste management companies, they would want it for free,” Mabuabu said, explaining that collectors are prone to sell to informal recyclers.

AUTHORITIES AND STAKEHOLDERS REACT

NESREA told TheCable that despite the agency’s efforts to curb the crude handling of e-waste, the high cost, inadequate recycling infrastructure, and lack of proper collection channels across the country continue to fuel the practice.

Abdusalam Isa, director of inspection and enforcement at NESREA, said though the informal sector plays a key role in the collection, “their activities must be restricted to collection only as they do not have the expertise to dismantle; otherwise, they would expose themselves to the hazardous substances in the e-waste.”

Isa further said between 2018 and 2024, UEEE imported with NESREA’s permission amounts to 757,033 pieces of equipment, while the quantity of e-waste collected is 301.5 tonnes.

“The quantity being recycled is small compared to the quantity generated either due to insufficient awareness and enforcement or inadequate capacity of enforcement officers, which needs to be built,” Isa said.

As part of the agency’s efforts to tackle the issues, the director said NESREA had recently concluded a Global Environment Facility (GEF) pilot project where over 300 informal collectors were “formalised” in Lagos. He added that the project will be replicated in other parts of the country.

Commenting on the activities of informal recyclers, Muyiwa Gbadegesin, managing director of the Lagos State Waste Management Authority (LAWMA), said it is “a struggle” to get scavengers to comply with regulations.

“You drive them from one place, and they move to another,” Gbadegesin said.

He explained that the Lagos government has signed a letter of intent (LoI) with a Netherlands company to build a smelting plant in the state. This, he said, will significantly address recycling challenges and improve revenue generation.

“Concerning recycling activities happening on the dumpsites, we want that to move away to community recycling centres in every local government, which will be drop-off points for members of the communities to bring their recyclables and get value for them,” the LAWMA boss said.

“We have an e-waste programme here at LAWMA and we work closely with EPRON and NESREA to bring stricter regulations to the e-waste sector.

“Many of the international off-takers are buying these products from the locals, and they are also not concerned about how the processing is done. Part of the agreement is to provide safety and regulatory measures that would make it safe. We don’t want to take people out of their means of livelihood, but we can do it better and safer.”

Ibukun Faluyi, executive secretary of the E-waste Producer Responsibility Organisation Nigeria (EPRON), corroborated reports that weak law enforcement is a key reason e-waste continues to be recycled illegally.

She also said scavengers offer more competitive prices for scrap items, pushing formal recyclers behind the scenes.

Faluyi further said EPRON partners with some electrical and electronic stores for takebacks, and offers training to personnel of the Nigeria Customs Service (NCS) to curb e-waste importation “because we know that without bringing customs in, our efforts will not be profitable”.

“You cannot do without giving an incentive for e-waste. Nobody is going to drop it and that is one of the things giving us challenges because the amount that the informal people are paying for it is a lot more than we can pay,” Faluyi said.

“The cost of managing the hazardous fraction of e-waste can be very high, especially because some of those facilities do not exist locally. So, people may then need to export, and that comes at a huge cost.

“There are warehouses where they have put in the high-level recovery processes, but it is highly polluting. Once we notice them, we tell the regulators.”

You can read the second part of the story HERE.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Add a comment