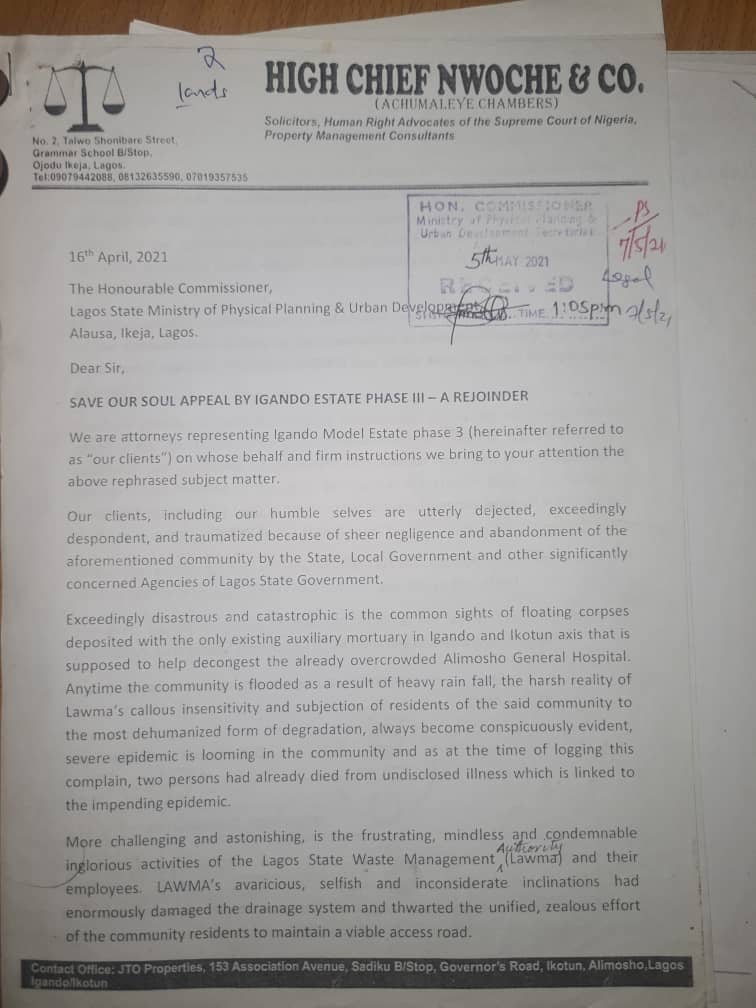

An aerial view of the landfill that occupy 12 hectares of land at Igando, Alimosho LG of Lagos

BY JEMILAT NASIRU AND IBRAHIM MANSUR

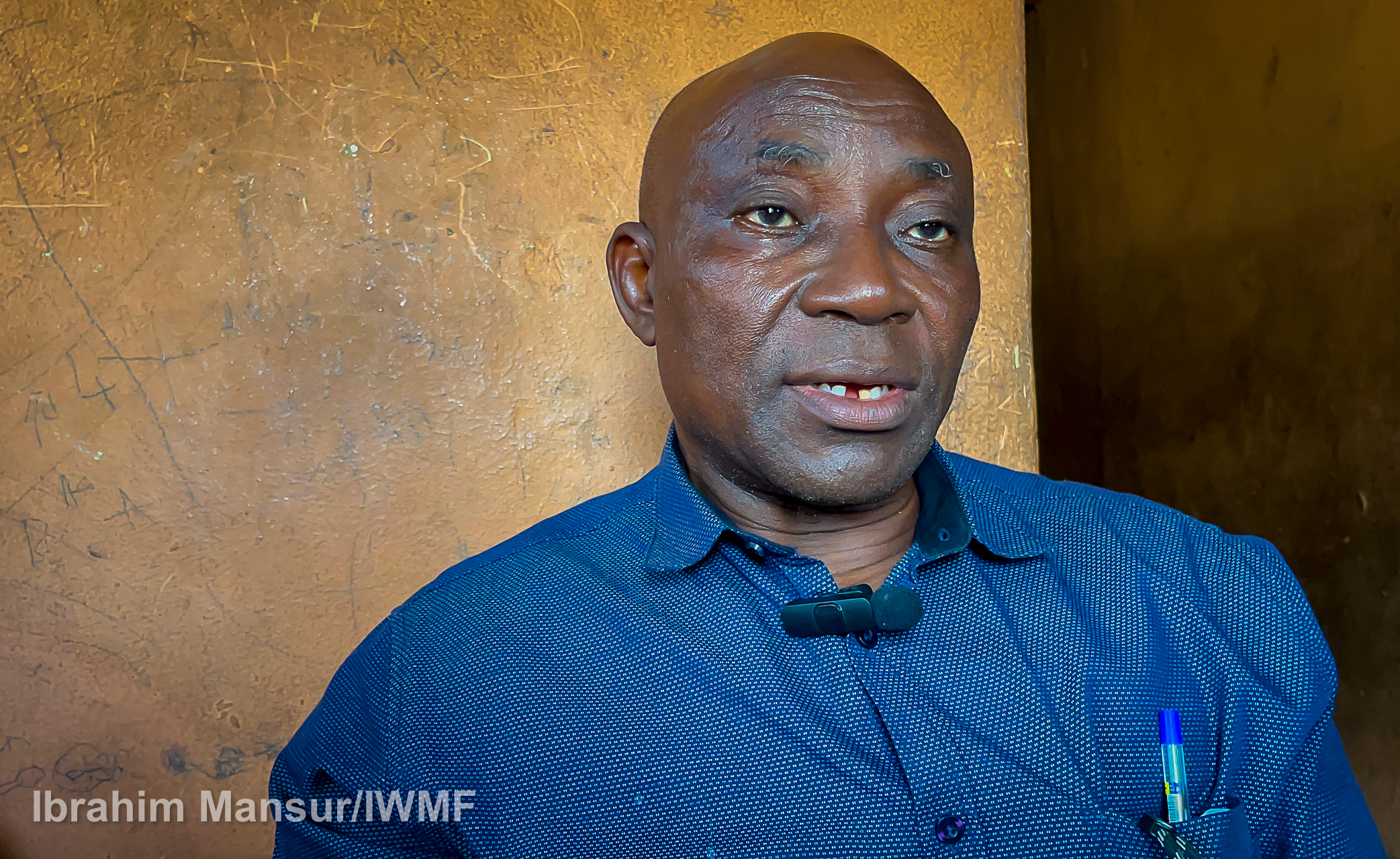

It took Peter Agboola three strenuous attempts to pronounce his name audibly. His eyes reddened and teared up with an overwhelming feeling of pain and helplessness that has now become his daily companion. At 63, his speech had become slurred after suffering a stroke, a development he blamed on his environment. Before sickness seized his agility, Agboola was a furniture maker. Nowadays, he sits at home all day long, gnashing in pain and anguish.

The air at Ogunmeru street in the Igando axis of Alimisho LGA is thick with the pungent odour of decay, a connivance of smells that assault the senses and linger long after one has departed. Adjacent Ogunmeru, where Agboola lives, is the Solous 3 landfill; the only thing between his house and the ten-foot distance from this mountain of decomposing waste is an untarred road. Agboola said his life took a drastic turn when the dirt came dropping.

The 12-hectare landfill, one of five government-run dumpsites in Lagos, is the only active of the three Solous in the area. It is the second largest dumpsite in Lagos, receiving a significant portion of the city’s 13,000 metric tonnes of daily waste generation. It is a place where the very definition of dump comes to life. The landfill has long surpassed its capacity yet continues to be stuffed, with refuse encroaching on host communities and spilling to the edges of people’s homes.

Advertisement

‘PEOPLE ARE DYING SLOWLY’

“We buried one last week” — Obasi

Breathing easy? Not in the Igando Royal Estate community and its environs. Ogedegbe Okweku, a resident of Odubanjo street, said when the reclaiming of the landfill with dirt first started, “it used to seize our breath”. His house shares a fence with the dump, and the leachate flows directly in front of his property and a primary school into a gutter.

Advertisement

Okweku lost his wife in 2021. He recounted bitterly how his late wife struggled to breathe in her last days. He said the pain of losing his wife caused him to develop high blood pressure.

“Recently, I fell sick. If not for God’s intervention, I’d have been a dead man by now. Three days ago, the odour intoxicated me like a drunk, and I started using my head to break my bathroom walls,” he said.

During an assessment tour of Igando Royal Estate by these reporters, the residents complained about how their health has deteriorated since the landfill commenced operation.

Another resident identified as Pastor Victor said he moved into the neighbourhood in 2018 as a “healthy man” but found himself frequenting the hospital for the first six months of his stay.

Advertisement

“When I told the doctor I reside behind Oko filling, he said, ‘and you dey look for wetin dey do you?,” Victor recounted. He was told his immune system struggled to adjust to his new environment.

Research has linked proximity to dumpsites with respiratory illnesses, malaria, skin irritation, asthma, and water and airborne diseases like typhoid, cholera, and dysentery. In extreme cases, residents could come down with cancers.

“There are incidents that have taken place here regarding lives wasted. They’re very painful,” Sam Ohwerhoye, chairman of Odubanjo street, said, tearing up.

“I know people are dying in their little ways because they don’t have the resources to take care of themselves. Some people are dying silently in this community.”

Advertisement

Bukola, Offe’s wife, also blamed the failing health of her retired naval husband on the environment.

“This is my husband; this is the result of everything. Instead of our children buying food for us, they’re buying us drugs. The doctor said the environment he is living in is affecting his lungs. He’s not breathing well, and he has cervical cancer. He has been sick for about three years.”

Advertisement

She added that it is not their wish to remain in the toxic environment slowly draining their lives. “We’re retired. Where are we going to get money to get another house?”

Advertisement

Speaking on the immediate and long-term effects of a dumpsite like Solous 3, Ernest Achalu, a professor of public health education and safety at the University of Port Harcourt, explained that exposure to contaminants from dumpsites can adversely affect all parts of the body, including the nervous and immune systems, liver, heart, and lungs.

He said residents living near the landfill are at a heightened risk of developing asthma, cancer, bronchitis, and experiencing DNA damage. Additionally, they may suffer from psychological problems such as anxiety and depression, which can significantly impact their overall social life.

Advertisement

Achalu urged the government to close the landfill and invest in infrastructure that promotes environmentally safe waste management practice.

INFRASTRUCTURE DAMAGE AND DECLINE

“Dirt came and development left” — Offe

The sole access road connecting the community directly to the expressway has been rendered impassable due to excessive dirt and debris. The once-motorable path has been bisected to accommodate leachate from the landfill. Residents are now forced to navigate the route by crossing some precarious wooden planks. The residents told TheCable that the previous week, a resident of Ogunmeru fell ill at night and had to be rushed to the hospital.

“This road was blocked and tattered, and we could not pass it to the general hospital. By the time they turned around to pass through Diamond Estate, everywhere was gated. By the time they got to the hospital, he was pronounced dead,” Victor recounted.

“We buried him last week,” Obasi, another resident, added.

Offe’s wife said water from their borehole is no longer potable, and her family and others rely on buying sachets or bottled water for their domestic needs.

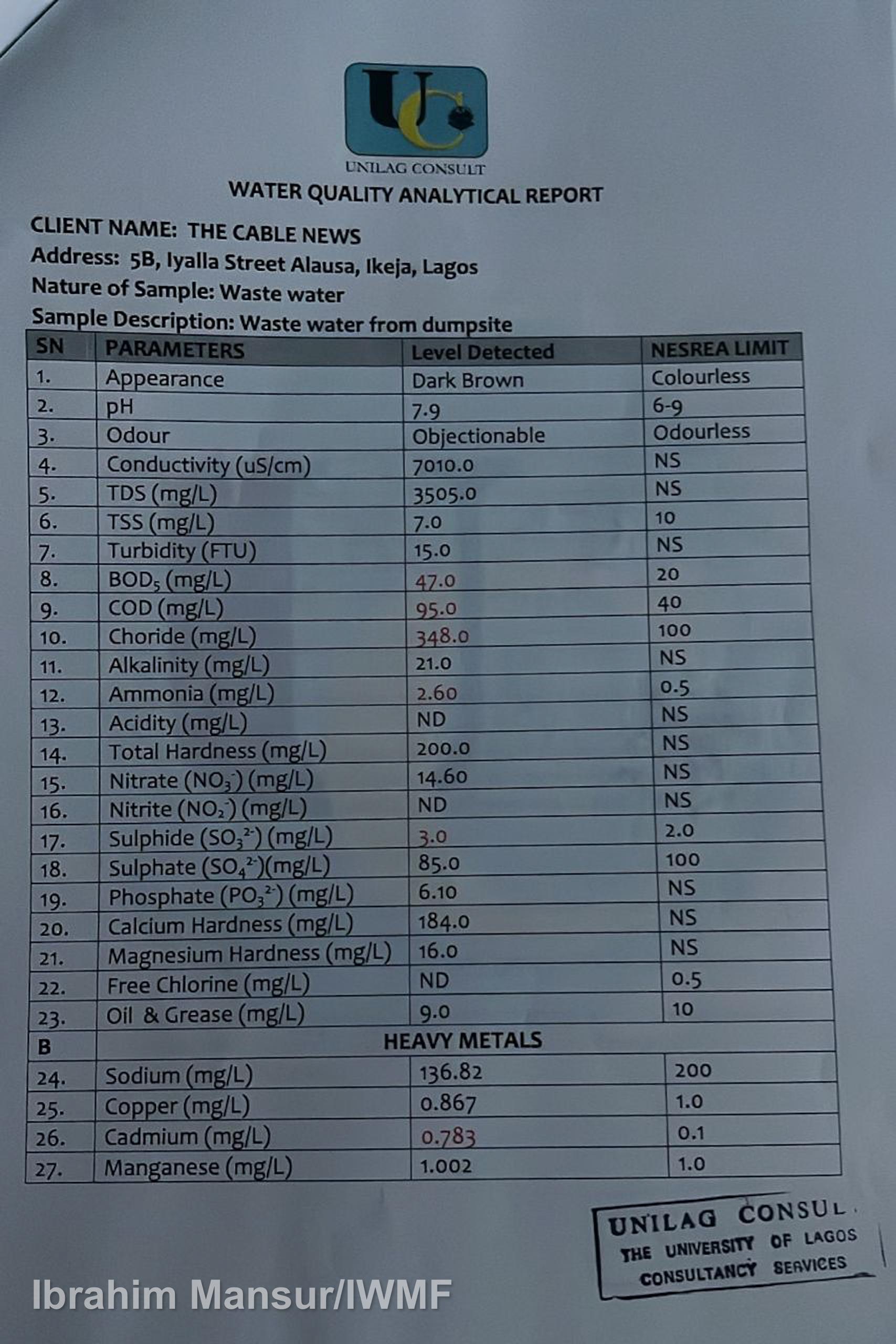

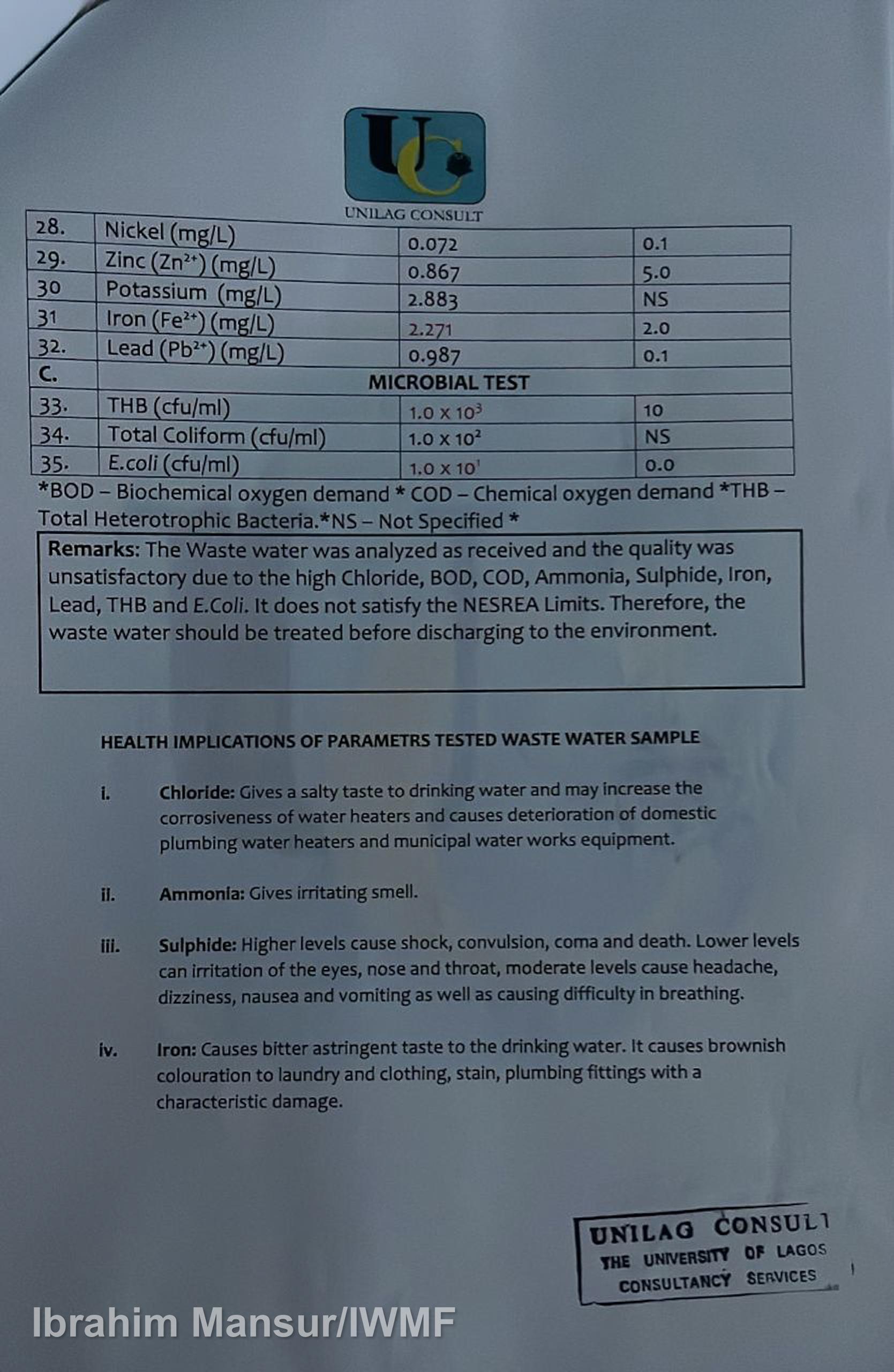

A water quality analytical report conducted by the University of Lagos laboratory on the runoff from the dumpsite showed high concentrations of lead, iron, chloride, cadmium, BOD, COD, ammonia in levels beyond limits set by the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA).

The report listed convulsion, coma, inflammation of the brain and spinal, spinal cord damage, and death as some of the health implications of the parameters of the wastewater.

A separate analysis of a sample of borehole water from a resident’s apartment found it contaminated and below the World Health Organisation (WHO) standards for potable water. While the analysis did not establish a direct link between the landfill runoff and the borehole water contamination, the presence of contaminants in the borehole water raises significant concerns about the potential health risks to residents.

Once a bustling hub of activity, Odubanjo street was home to Rosellas, an amusement park that drew crowds from across the state. The street also boasted a steel plant and a plastic company, but these businesses were forced to close their doors after repeated flooding devastated the community. The absence of a proper drainage system left the area vulnerable, ultimately leading to the decline of these once-thriving businesses.

Ohwerhoye told TheCable that during intense rainfall, the flood washed out dead bodies from a nearby mortuary, leaving them floating on the surface.

The Alimosho General Hospital, situated less than 3 kilometres from Solous 3 main gate, is grappling with the pervasive stench emanating from the landfill. This noxious odour has discouraged numerous residents from seeking medical treatment at the facility, despite its convenient location. Patients and healthcare professionals within the hospital are subjected to constant discomfort as trucks transporting waste pass by the hospital entrance, leaving a lingering trail of foul-smelling emissions.

Despite repeated promises to close Solous 3, the landfill remains operational. In 2017, the Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA) announced plans to close down the dumpsite in the second quarter of 2017.

Two years later, Akin Abayomi, former health commissioner in Lagos, said it was unacceptable for a general hospital to be flanked by a dumpsite. He also added that the state government was aware of the “discomfort and agony” caused to residents in the neighbourhood.

Abayomi said plans were in place to decommission the landfill and convert it to an energy-generating plant. But as of press time, there is no public record of any steps taken.

DID THE DIRT COME TO PEOPLE OR PEOPLE TO THE DIRT?

The precise year of operation for the Solous 3 landfill remains uncertain, with conflicting sources. Residents vehemently claimed that they purchased their properties and constructed their homes well before the landfill operations began. According to Ohwerhoye, he moved to his apartment in March 1998, finding the land lush, verdant, and teeming with beautiful flora.

Similarly, Okekwu recounted acquiring his land in the same year, describing it as an idyllic location. He said he moved into the property in 2005, and the landfill was not yet in existence.

While this 2012 article published in the American Journal of Environmental Engineering, suggests Solous 3 landfill “commenced operations” in 2008, a 2021 publication in African Journals Online places the “opening” year of the landfill in 2006.

But Muyiwa Gbadegesin, managing director of LAWMA, disagreed with the submission of the residents. The MD said the landfill was situated away from residential areas but development caught up with it.

LAGOS LANDFILLS POORLY MANAGED

Despite LAWMA’s acknowledgement of the subpar waste management practices at Lagos’ dumpsites, the agency has been unable to implement effective solutions. The agency noted that waste landfills should be set up and operated properly to minimise health and environmental risks.

However, the agency admitted that landfills within the Lagos metropolis are “uncontrolled and do not conform to international standards of similar operations elsewhere in the world”.

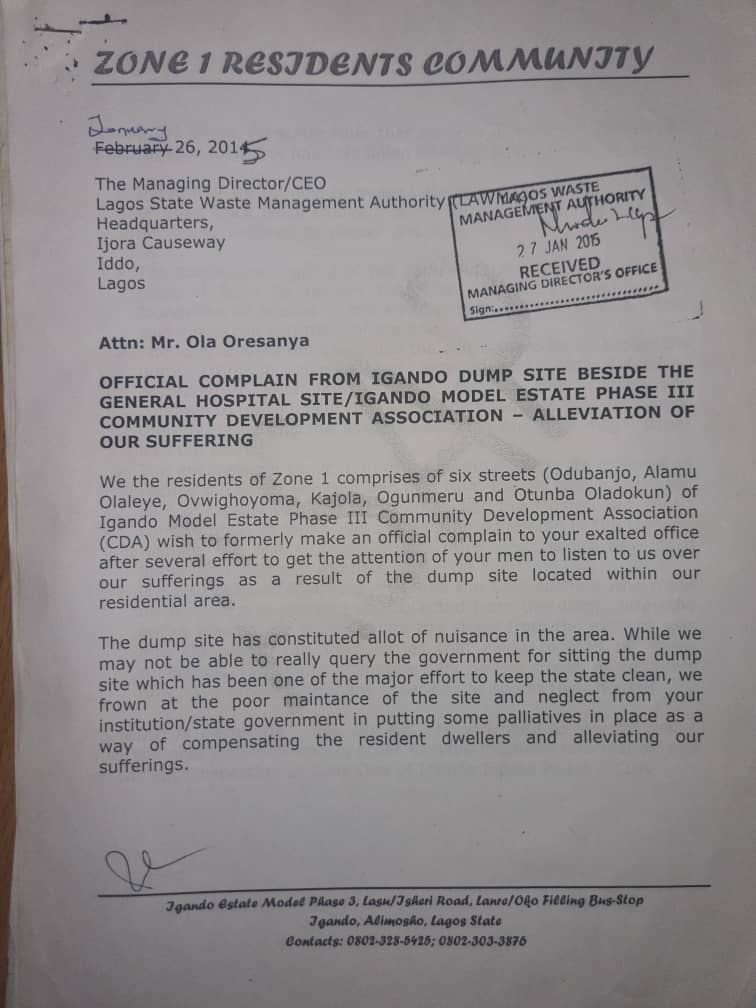

Solous 3, originally intended as a landfill, functions more like a dumpsite. Despite repeated government announcements and deadlines to decommission it, the growing mountain of waste persists. Residents have tirelessly advocated for change, but their efforts have been met with inaction. Even though they acknowledged the petitions and letters, the state government has taken no concrete steps to address the situation.

Residents recounted instances of government officials visiting the site and promising improvements, only to see superficial measures like pouring red sand in some parts of the facility to disguise the problem.

“There is nowhere we haven’t gone to, no office we haven’t entered. We went the legal way yet nothing changed,” Okweku said. “They can’t say they don’t know us.”

Gbadegesin attributed the greatest challenge to waste management in Lagos to human behaviour and the unavailability of land. He said most of the 13,000 tonnes of waste generated daily go to five of the landfills in the state, including Solous 3, which has long been due for decommissioning.

“But if we close those sites, tell me if you know any community in Lagos that will be happy for LAWMA to come and open another landfill close to them,” Gbadegesin asked.

He explained that the state would eventually have to embrace the zero-waste principle — reduce, reuse, and recycle. This, he said, would help save the environment and grow the circular economy.

Gbadegesin further said that Solous 3 and Olusosun landfills in Ojota have reached the end of life and must be decommissioned within a year. “That’s the maximum useful lifetime that we have left,” he said.

To achieve this, the MD noted that the state government has signed a memorandum of understanding with a Dutch company that specialises in waste treatment. He said the MoU will see to the treatment and recycling of 5,000 tonnes of waste daily, leading to a significant reduction in the trash that goes to the dumpsites.

Asked if there were any plans to compensate residents who suffered attributable health impacts or property loss, Gbadegesin responded in the negative. “What we can do is fix the problem and close the dumpsite,” he said.

Will LAWMA live true to its word to decommission the landfill this time? Until then, the dumpsite continues to claim more territory and choke its hosts, and even the dead are not spared.

While she was alive, Mrs Okweku shared a fence with the landfill, and in death, the pungent smell of waste that haunted her days hangs over her resting place, which is nestled beside her home — a constant reminder and torture for her husband, who has lost hope for a change in the situation. He has told his children that should he take ill again, he should be left at home to his fate if over-the-counter medications do not bring him relief.

You can read the first part of the story HERE.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G Buffett Fund for Women Journalists.

Add a comment