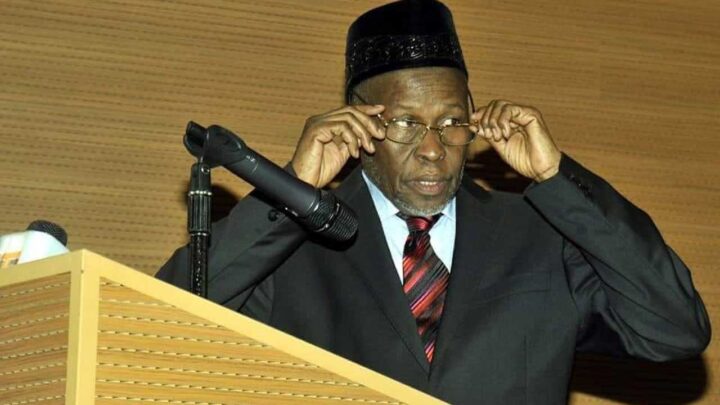

PRESIDENT BUHARI PRESIDES OVER POLICY RETREAT A. The New Chief Justice of Nigeria (CJN), Hon Justice Tanko Muhammad takes his oath of office held at the Council Chambers at the State House Abuja PHOTO; SUNDAY AGHAEZE. JULY 24 2019

The resignation of Tanko Ibrahim Muhammad as chief justice of Nigeria (CJN) is perhaps the remotest thing anyone would have anticipated at the start of the week.

Muhammad, 68, was said to have resigned on the grounds of ill-health. But TheCable learnt he was forced to quit his position because of corruption allegations.

Some justices of the supreme court had threatened to stop sitting by September if Muhammad was not removed as CJN.

They accused him of incompetence and corruption.

Advertisement

Muhammad’s resignation comes about 18 months before his retirement in December 2023, when he will clock 70.

CONTROVERSIAL APPOINTMENT

Muhammad was sworn in as substantive CJN on July 24, 2019 — six months after he assumed office in acting capacity.

Advertisement

His predecessor, Walter Onnoghen, was suspended in controversial circumstances by President Muhammadu Buhari in January 2019 over allegations of non-asset declaration.

Onnoghen was never returned to office following his resignation and conviction by the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT) — nearly two years before he was scheduled to retire in December 2020.

The appointment of Muhammad elicited negative reactions with many, including senior advocates of Nigeria, speaking against his confirmation as substantive CJN.

Olisa Agbakoba, senior advocate of Nigeria (SAN), had demanded the removal of Muhammad as the acting CJN over alleged misconduct.

Advertisement

“Hon. Justice Tanko Mohammed is fully aware of the state of law, yet presented himself to be sworn in by the President,” Agbakoba wrote in a petition to the National Judicial Council (NJC).

“Incidentally, Justice Tanko Mohammed was a member of the NJC panel that removed Justice Obisike Orji of the Abia state High Court for accepting to be sworn in as Chief Judge by the Governor of Abia state without the recommendation of the NJC.

“It is a matter of regret that Justice Tanko Mohammed who participated in this process will lend himself to this constitutional infraction.”

Although there were other petitions as well as suits against Muhammad’s appointment as CJN, none of them sailed through.

Advertisement

DOGGED BY ILL-HEALTH

During his tenure as CJN, there were speculations and concerns over Muhammad’s health.

Advertisement

In 2020, the CJN was unusually absent from a number of important functions.

In December of the same year, TheCable learnt that he had been ill and was due to be flown abroad for treatment.

Advertisement

But his spokesperson as well as the supreme court administration insisted that he was in good health.

A SHARIA EXPERT

Advertisement

Muhammad, who was between 1991 and 1993 a judge of the Sharia Court of Appeal, Bauchi state, was quite expressive about his views on Sharia.

In December 2019, he called for the amendment of the constitution to accommodate more aspects of the Sharia law.

“As we all know, there are sections of the constitution that allow the implementation of Shari’a personal law and apart from that, we cannot do more. However, we have the numbers to amend the constitution to suit our own position as Muslims,” the CJN said.

His statement stirred controversy with many, including the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) calling for his removal.

But he majored in Sharia law and was elevated to the supreme court on that basis — because many Sharia cases end up at the apex court.

‘IRRESPONSIBLE’ JUDGE

It is a widely-held opinion that the outgoing CJN did not care much about the affairs of the judiciary and more importantly, about the welfare of judicial officers.

This position was affirmed a few days ago when a letter by 14 justices of the apex court surfaced online.

Some of the issues raised by the justices include — accommodation, vehicles, electricity tariff, supply of diesel, internet services to justices’ residences, training for justices and epileptic electricity supply to the court.

The justices accused the CJN of going on foreign trips with his family and demanded to know what had become of funds set aside for training of justices since they have been denied the usual two to three international workshops annually.

In the letter which they described as a “wake-up call” to the CJN, the justices said: “It is either you quickly and swiftly take responsibility and address these burning issues or we will be compelled to further steps immediately.”

In 2019, the CJN was also alleged to be involved in bribery in a case involving Sani Dauda, owner of ASD Motors.

The EFCC had arraigned Shehu Sani, former senator, for allegedly taking money from Dauda, promising to pass it on to Ibrahim Magu and influencing the outcome of some cases using his connection with the CJN and some other judges.

The CJN, however, denied being involved in such unethical conduct, stating that he had never met Sani.

IMO JUDGMENT CONTROVERSY

The CJN chaired a seven-man panel of justices which presided over the appeal on the Imo state governorship election.

Hope Uzodimma, governor of Imo, had through his lawyer, argued that both the tribunal and the court of appeal erred by throwing out his petition against Emeka Ihedioha, then governor of the state.

He argued that Ihedioha did not score the highest number of votes in the governorship election — because results from 388 units were excluded from collation by INEC.

The panel led by the CJN agreed with the appellant’s argument and affirmed Uzodimma (who came forth in the election) as the duly-elected governor of Imo.

However, Chima Nweze, one of the judges, disagreed with the ruling.

In his dissenting judgment, Nweze asked the court to set aside the January 14 judgment that removed Ihedioha from office, describing it as a nullity and in bad faith.

Centus said: “This decision of the supreme court will continue to haunt our electoral jurisprudence for a long time to come.”

Muhammad’s exit, couched as a decision based on medical advice, is less than what he would have preferred — especially with the allegations against him by the justices as well as around his family members.

Add a comment