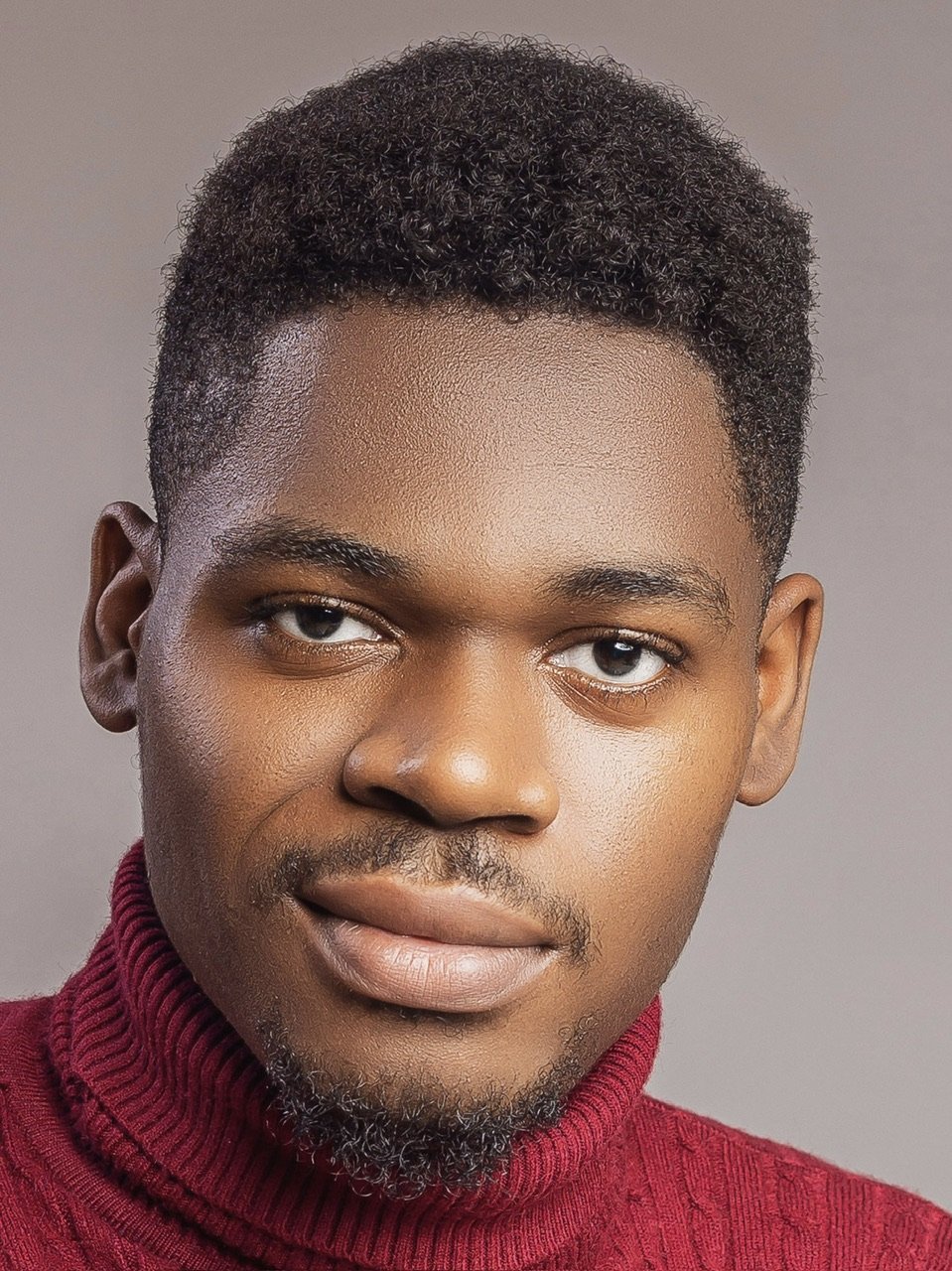

Matriculating students at Federal University Lokoja's Adankolo Campus on April 10, 2018.

Kogi recently began implementing a policy requiring new and returning students in state-owned tertiary schools to provide their parents’ tax clearance certificate as a condition for registration.

Sule Salihu Enehe, the chairman of the state internal revenue service, had issued a directive to institutional heads via a circular marked “KGIRS/PIT/ Vol.5/11647″, dated November 26, and titled “Enforcement of tax clearance as a condition for student registration”.

The state said the policy, enacted in January, is intended to enforce tax compliance and “shore up” state revenues. Enehe said it had undergone a test run and had been introduced at Federal University Lokoja as of 2023, but it is only now being adopted on a larger scale.

The policy was said to have been proposed to the IRS by the secretary to the state government (SSG) about three years ago. It hinges its legitimacy on section 24(f) of Nigeria’s constitution, a blanket law that requires citizens to declare their income and promptly pay tax.

Advertisement

Section 85, subsection 4(v) of the Personal Income Tax Act stipulates a list of “transactions” for which a ministry, department, agency of government, or commercial bank can require an individual to obtain and submit a tax clearance certificate.

This federal law, which was last amended in 2011, does not explicitly state that the acquisition of public (tertiary) education is one such transaction. It includes a clause that captures “any other [transaction] as may be determined from time to time” by the government.

However, the PIT Act does not empower these MDAs to enforce tax compliance “by proxy”. This raises questions as to why students, who are independent adults in their own right, would be required to prove the tax compliance status of their parents to access education.

Advertisement

Rights activists, parents, analysts, policy experts, tax lawyers, and education sector stakeholders have criticised the policy.

Critics have labelled the policy harsh and discriminatory, particularly for self-sponsored students and those from low-income families or outside the state. Others argue that the requirement was not part of the admission conditions and could deny many students access to education.

Some others appear to support the policy, arguing that tax-compliant individuals should have no problem proving their annual filings.

IRS SAYS POLICY IS TO JUSTIFY SUBSIDY ON TERTIARY SCHOOLS

Advertisement

Muhammad Idris, the corporate affairs head at Kogi IRS, told TheCable that the policy seeks to justify the state’s subsidisation of tertiary schools and verify tax compliance in a manner that is sensitive to indigent people, self-sponsored students, and other exceptional cases.

“We’re not holding anyone to ransom. Asking that the students submit TCC does not mean paying any additional money. It’s just to show tax compliance by the parents, guardians, or whoever is a guarantor for the student,” Idris said.

“It’s been over three years since the SSG sent the circular to all state-owned tertiary institutions. This includes the university, the college of education, the school of nursing, and the school of health technology.

“Some pleaded for implementation to be delayed to give room for sensitisation. That window was given to them. Last year, the revenue body wrote a letter to remind the institutions about the SSG’s circular.

Advertisement

“We told them, during budget defence, that implementation must commence this year. That is what we’re doing.

“Someone from Ekiti, as a non-indigene of Kogi, can present an Ekiti TCC. Education in Kogi sticks to the calendar. For this, Kogi had put structures on the ground. The government needs money.”

Advertisement

The amount of subsidy provided by Kogi to its state-owned tertiary institutions is not publicly disclosed, but such support typically takes the form of direct financing, fee waivers, and investment in infrastructure.

Neither the IRS chair himself nor Ismaila Isah, the media adviser to the Kogi governor, gave further comments when contacted on this.

Advertisement

An analysis of Kogi’s budget performance for Q1, Q2, and Q3 shows the state had met 78.7 per cent of its projected PIT revenue for 2024 by the third quarter, raking in N11.3 billion and being well on its way to hitting the expected N14.2 billion for this tax category.

Budgit’s State of States report noted in 2024 that PIT inflows have the potential to generate as much as 86.2 percent of tax revenue in some states.

Advertisement

However, the impact of Nigeria’s proposed tax reforms on revenue generation in many states, including Kogi, remains uncertain.

RIGHTS ACTIVIST THREATENS SUIT

Miliki Abdul, executive director at the non-profit Conscience for Human Rights and Conflicts Resolution, said it would be “unfortunate” and “ridiculous” if a student registers and meets all admissions criteria but is denied the right to education due to Kogi’s novel TCC rule.

Agabaidu Jideani, a commissioner presiding over education rights matters at the National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria (NHRC), warned the Kogi state government against allowing the pursuit of tax compliance to infringe on the citizenry’s right to acquire education.

Activists like Arome Odoma are challenging the policy’s legality, filing a pre-action notice addressed to Usman Ododo, the state governor.

On the contrary, Theophilus Emuwa, a tax lawyer, argued in an interview that it is within the rights of tertiary schools to mandate that students (or whoever is paying the fees to train a student in a public institution) prove that they are tax-compliant.

“It is not something new. If the student is self-sponsoring and has a day or night job, then they prove it. Even abroad, students are offered part-time jobs from which they can pay their way. I imagine that is probably just one out of 100 cases there could be,” he said.

“There are about 20 items on the PIT Act for which citizens must show tax clearance. How can states enforce the law without being as forceful as they have to be? How will they enforce tax clearance if they don’t bring it up when citizens try to access a government service? Nobody will pay!”

ONE POLICY, MANY ISSUES

Ethical, legal, and practical concerns persist as to how Kogi’s TCC policy amounts to a form of proxy enforcement, shifting the burden of ensuring parental or guardian tax compliance onto students who are seemingly being co-opted as unwitting second-hand tax police.

Admission seekers, many of whom are adults around age 18, are compelled to present documents tied to the actions (or inactions) of their parents or guardians, arguably undermining student autonomy and placing them in a position of dependence on the compliance of others.

The policy also willfully assumes that all students have accessible and compliant parents. It almost maliciously disregards those from estranged or abusive family situations, who are self-sponsoring/orphaned, or whose guardians are simply unwilling to comply.

Tax evasion is a long-standing problem in Nigeria, with compliance rates remaining low partly due to a lack of data on the informal sector, despite federal efforts. A 2024 report, for instance, estimated that up to 99 per cent of even high-net-worth individuals in Nigeria dodge tax obligations and exploit a system devoid of a comprehensive registry of wealth and beneficial ownership of financial and non-financial assets. Lack of trust in the government’s ability to use tax revenue effectively for public services also contributes to low tax compliance rates. Should students now be burdened with a systemic problem that Nigeria’s tax office struggles with and has been unable to solve?

Analysts argue there is a coercive and discriminatory ring to Kogi’s TCC rule, where enforcing unrelated tax compliance through such a fundamental human right as education could be challenged in court as limiting accessibility.

Oluwatoyin Ajilore-Chukwuemeka, an education policy expert, acknowledged state efforts to work out “creative” tax enforcement strategies. She, however, expressed concern about what she describes as policymaking done without exhaustive stakeholder consultation.

“Tax compliance and university education are not things to be connected. It’s not proper to lump parent and child together, where the failings of the former debars the latter’s access to education,” she added.

“Wider access to education is one thing Nigeria desperately needs. We shouldn’t erect more roadblocks to people’s ability to access tertiary education. Policymaking is meant to be a public process, not a directive.”

Hitching access to vital services like education to proxy tax compliance is rare and controversial, with few global precedents. If Kogi’s TCC rule sails, it could embolden other states to adopt similar policies, potentially reshaping the social contract between citizens and government.

What this could mean for education equity and how it would affect students from low-income or fractured homes remains to be observed.

Add a comment