Life at Mosquito village, a slum in Lagos state, is disgusting, brutal, weird, ephemeral, yet entertaining. The residents live in the cozy embrace of the filth surrounding them like the walls of Jericho — but life must go on. Their reality is gloomy but with daily doses of jest, they wade through the murky waters of their world. TAIWO ADEBULU, who visited the small community, reports.

That foggy evening, the cloud of filthy smoke enveloped the alley of the sprawling shanties on the swampy piece of land stretching along the shores of a tributary of the Lagos lagoon. As an unknown figure sauntered into their community, the women frying assorted snacks stared frigidly, with curiosity plastered on their faces. With one hand, a restless young woman scooped the buns from the simmering vegetable oil; with the other hand, she wiped the stream of sweats zigzagging across her cleavage.

Narrow is the path, they say, that leads to heaven. The road to Mosquito village, a slum in the suburb of Ajegunle in Ajeromi Ifelodun local government area of Lagos state is narrower — but the village is no heaven.

Meandering through the tiny labyrinths, one often comes across little children running helter-skelter across the marshy ground littered with plastics and all kinds of disposables. The houses built with wooden planks are lumped up providing little or no space for ventilation and passage, yet it offered a perfect stage for a hide-and-seek game for the scarcely-clad children.

Advertisement

Surrounded by heaps of refuse, the community of fewer than 2000 residents seems indifferent to the dingy environment they call home. After all, they have shelter and they do not have to pay annual rents to the impatient Lagos landlords. Hence, the land reclaimed from the dark river separating them from Tincan Island Port, Nigeria’s second-busiest port is indeed a promise land.

SPRANG FROM A RECLAIMED LAND

Sixty-two-year-old Zachariah Mowojaye, chairman of Mosquito Village, gingerly relayed with graphic details how the settlement came to be. His genteel voice was punctuated by frequent pauses as he adjusted his glasses to speak.

Advertisement

“This place was initially swampy and waterlogged. When Tincan Island Port was being constructed in the late 70s, they filled this place with the soil reclaimed from the lagoon. The federal government probably reserved this place for customs officials to thwart the activities of smugglers in the waterways. After they filled the land, they didn’t use it. They just built a house on it,” he said.

“When Lateef Jakande became the governor of Lagos in 1979 under the Unity Party of Nigeria, he initiated elaborate educational reforms for the poor and he started building neighbouring schools. That was because schools were not enough and the population was increasing.

“So, he came to Tolu a few metres from here and realised that the land was vast and vacant. Then, he jumped on the land at Tolu complex and built about 20 schools. That exposed this area to people. Soon, people who couldn’t afford to pay house rents started moving to the base of this river to build makeshift houses with planks. Later, low-income workers from the port and civil service joined the residents to abate the burden of renting an apartment in town.”

MOSQUITOES WERE THE EARLY SETTLERS

Advertisement

Stating why the settlement was called Mosquito village, Zachariah said the place was bushy when people started moving there.

“So, when outsiders come to visit us, they complain about the high presence of mosquitoes. Really, the mosquitoes were very fat. Even in the afternoon, the mosquitoes go about their business unperturbed. So, when those visitors go out there and people ask them where they were coming from, they tell them that they visited that slum where mosquitoes predominate. That was how the name stuck.

“Now, the mosquitoes do not prevail again because we have fewer bushes and the population has increased. But in some seasons, they troop here like they’ve come for their festival.”

Folorunsho Asogbon, who corroborated Zachariah’s statement, said he was the first person to settle in the area in 1989.

Advertisement

“I only met the mosquitoes here, after which I built my house at the bank of the river. When I came here, the mosquitoes were in their highest population. But now, we no longer feel their impact because they have shared themselves among the growing population,” he said.

Taye Kasali, a 50-year-old fruit seller who had been living in the settlement since 2009, said: “white men” used to shoot movies at the waterfront.

Advertisement

“We were afraid when we started living here. Some people used to call this place trinity because it was a favourite site for burying the dead. Since the mosquitoes reduced, we’ve been battling with flies.”

THE POPULATION INCREASES BY THE DAY

Advertisement

According to the United Nations Habitat, 30 per cent of the world’s urban population resides in slums, with deplorable conditions where people suffer from several deficiencies. At the 2016 World Habitat Day organised by the Lagos state ministry of physical planning and urban development, Akinwunmi Ambode, governor of the state, said there was the need for additional 187,500 new houses in the next five years to reduce the housing deficit estimated at 2.5 million in the state.

As the cost of house rent is fast increasing in most Lagos metropolis, residents who cannot afford the prices are moving to the slum. Just pay N2000 to miscreants popularly called area boys, who have constituted themselves as omo onile (landowners), then you will be apportioned a space where you can build your house. Failure to ‘settle’ the so-called landowners will result in your house being demolished.

Advertisement

However, with the rising population and the wobbly wooden houses muddled with reckless abandon, an untreated infection can lead to a huge outbreak of diseases, even though the closest hospital is several kilometres away.

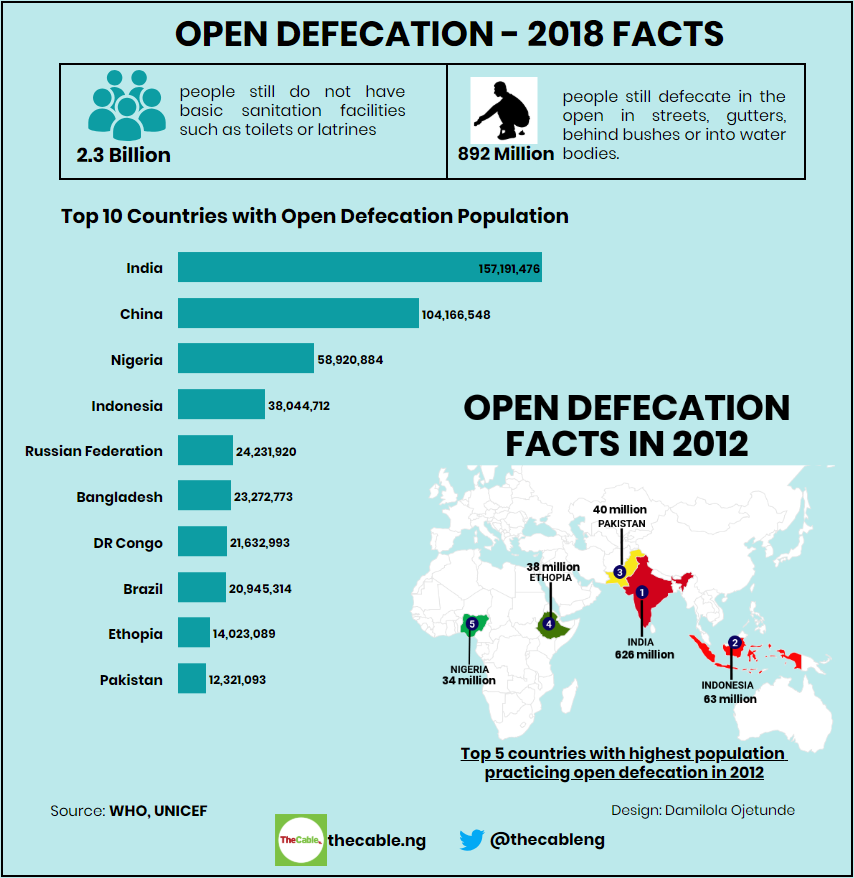

Residents of the village practise open defecation, while access to potable water is practically nonexistent.

“WE PREFER TO USE WATER”

Some humanitarian agencies, including the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), came to the aid of the inhabitants of the community by providing some social amenities. UNICEF provided an eco-friendly toilet which was launched on May 18, 2015. The restroom was built at the base of a mountain of refuse popularly called Bolar. TheCable gathered that the residents didn’t use it for two months before abandoning it. They reverted to defecating in makeshift toilets built at the tip of the lagoon.

Thirty-seven-year-old Sharafa Salami, who has been living in the settlement for eight years, said they stopped using the toilet because it doesn’t give them the luxury of using water.

“We stopped using it because it wasn’t convenient for us. While the toilet doesn’t allow us to use water, we still prefer it to tissue paper. A tissue paper doesn’t clean ‘it’ as much as water. Worse still, you must not throw the paper in the toilet after use. You’ll drop it inside a wastepaper bin and the person in charge of the toilet gets rid of it. We used to pay N20 for a session,” Salami told TheCable.

“This new toilet technology is alien to us. So, we prefer to defecate on this heap of refuse, while those whose houses are closer to the lagoon use the wooden toilets.”

But at night, no one dares climb the refuse to relieve himself, lest he is disposed of his valuables by the lords of the night who take charge of Bolar at night. So, when nature calls, one does it in nylon, keeps it somewhere and waits till morning to discard it.

A damning joint report from UNICEF and World Health Organisation (WHO), released to mark World Toilet Day in 2012, revealed that an estimated 34 million Nigerians have no toilet and practice open defecation. It ranked Nigeria among the top five countries in the world with the largest number of people defecating in the open, a good majority of which comes from Lagos owing to its large population.

In March 2018, another report from WaterAid Nigeria, an international non-governmental charity organisation, said that about 60 million Nigerians do not have adequate access to water, 120 million lack decent toilets and 47 million practise open defecation.

NO POTABLE WATER

In addition, UNICEF provided a water facility for the residents; this also is no longer in use as the people patronise local water sellers. In the absence of a potable water supply, they buy sachet water for drinking.

Badmus Isiaka, a 36-year-old commercial driver, said they couldn’t pump the water because residents were not contributing to it, hence everyone patronises the services of local water vendors.

“The vendors sell water for us from the water tank in their boats. We don’t know where they get it from, but we have no choice. We do not drink it because it’s not hygienic, but it’s good for domestic use. A keg of water is N10,” he said.

“I have two wives and two children. Sometimes, we use sachet water for bathing. Three kegs hardly last for a day.”

Chichi Aniagolu-Okoye, country director of WaterAid Nigeria, said, “We know that if everyone, everywhere was able to access clean water, decent toilets and good hygiene, then we could help end the scourge of extreme poverty and create a more sustainable future.

“WE ARE POOR PEOPLE, BUT WE ENJOY OUR LIVES”

While the UNICEF statistics, in Nigeria, estimated that diarrhoea kills about 194,000 children under five every year and in addition, respiratory infections kill another 240,000, which are largely preventable with improvements in water, sanitation and hygiene, most residents of Mosquito village say it is not a source of worry since they hardly fall sick.

“We hardly get sick. Our skins have grown thick to the environment. We know we are poor people, but we enjoy our lives and freedom here,” Zachariah quipped with an aura of resignation.

Yet, the residents have to cope with the noisy activities from the ever-busy port every day as though the clatters of containers and banging cranes were the sonorous chirping of nocturnal birds. In the morning, the workers cross the river to the port, while the fishers delve into the faeces-infested lagoon to catch fishes, which they sell to their neighbours.

“Once in a while, I fish in the lagoon with one of my uncles and we used to catch big fish, but it depends on the season. We also swim in the water,” Godwin Mowo, a 15-year-old boy, told TheCable.

Residents of the slum cut across different tribes in Nigeria. Prominent among them are the Ilajes, an ethnic group from Ondo state, the Eguns from Badagry in Lagos, Ijaws from the Niger Delta region, Igbo from the south-east region and a handful of Hausas. In the evening, the men gather at the beer parlour to discuss politics and trendy news, while they gently quaff the boozy liquid from the green bottles. Some gather to play drafts, while the lily-livered ones count the scores. The women chat away; some attend to house chores.

However, the many-cornered scenery of clustered houses with the backdrop of tattered clothes provides a sensational adventure for night lovers. As small as the settlement is, sandwiched in-between buildings are churches of different denominations.

“This place used to be the most beautiful place in Ajegunle, until they started dumping refuse here,” Folorunsho recalled with nostalgia.

FEAR OF THE UNKNOWN

Kasali puts it succinctly, “We know our stay here is temporary because it is not our land. We only came here to settle because of our condition. No one really desires a home made of planks.”

According to Folorunsho, they are aware that the land belongs to the government; that’s why none of the residents has a certificate of occupancy.

He said, “Now that they want to turn Lagos into a megacity, we are afraid they might eject us from here and level our homes. I don’t know when it will happen, but I know it will definitely happen.”

While the residents nurse the fear of the unknown, they wouldn’t let the life that fate has plunged them into get the better of them. Hence, they live every day in conscious denial of their world.

Add a comment