In the last two years alone, there have been a number of questionable deaths involving secondary school students across Nigeria, relating to alleged bullying, harassment, corporal punishment, or institutional negligence. Central to these cases are the police who — armed by law — are tasked with undertaking probes meant to uncover the circumstances that claimed the lives of the students. However, some of these cases either drag on for too long or go unresolved. Over the course of one month, TheCable’s STEPHEN KENECHI traversed local communities across different states, followed court sittings, perused documents, spoke with parties to the cases, and consulted experts to examine the place and pace of the police investigations.

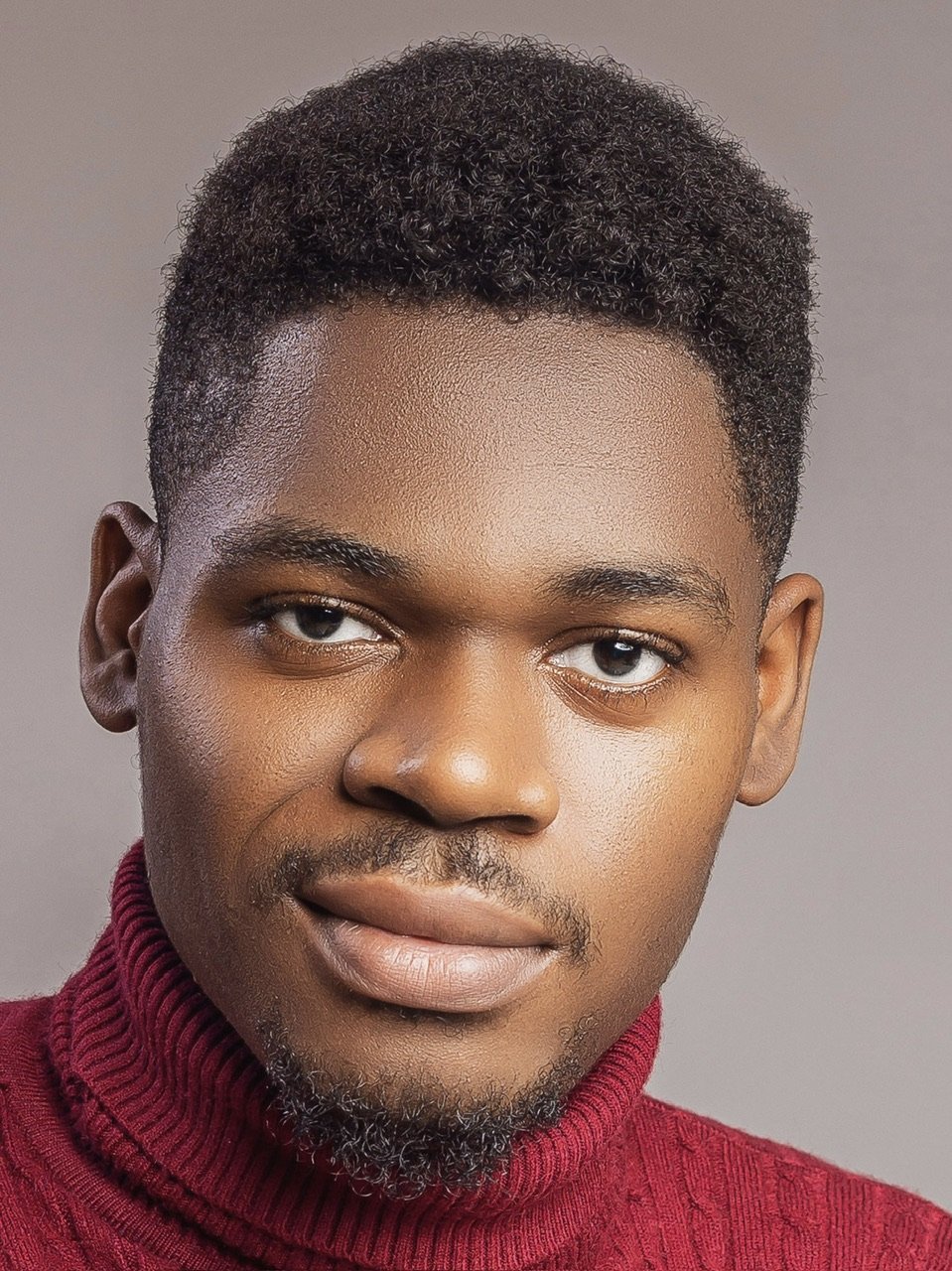

SYLVESTER OROMONI: LONG ROAD TO JUSTICE

It took public rage and media frenzy to spur a police investigation in the case of Sylvester Oromoni, a pupil of Dowen College Lagos who died in November 2021 after he was alleged to have been bullied and beaten by five of his colleagues. His father had claimed he was attacked and fed a chemical. Dowen dismissed this, insisting that the boy sustained injuries playing football with his friends.

Hakeem Odumosu, the erstwhile Lagos police commissioner, ordered a probe while the school was sealed off. Two autopsies were conducted on the deceased — one by the Delta police and the second by the force’s Lagos command.

The first autopsy declared that Oromoni died of “acute lung injury due to chemical intoxication” but it was subsequently discredited on the claim that only the bereaved’s family witnessed the autopsy.

Advertisement

After the Lagos police probe, Odumosu forwarded the findings to the state department of public prosecution (DPP). The DPP’s verdict, backed by the second autopsy, declared that Oromoni died naturally, not by poison.

The autopsy and toxicology reports by the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH) and Central Hospital Warri declared that the causes of Oromoni’s death were septicemia, lobar pneumonia with acute pyelonephritis, pyomyositis of the right ankle, and acute bacterial pneumonia due to severe sepsis. The case has since been under a coroner’s inquiry, with the father of the student vowing to pursue the matter up to the apex court.

‘INCOMPREHENSIVE’ POLICE PROBE

Advertisement

TheCable obtained an audio recording from Sylvester, Oromoni’s father, which allegedly features a Dowen student confessing that the deceased was beaten up by seniors a week before his health deteriorated. The student, who is said to have been friends with the late Oromoni, said he witnessed the incident. In the audio, the father of the witness could be heard complaining that pupils like his son who dare to speak to the police were intimidated and called “snitches”.

Bamidele Olusegun, an IPO at the state criminal investigation department (SCID), who headed the police probe, told the court that only four of seven roommates of the deceased, who potentially witnessed the attack, were questioned as the parents of the remaining three didn’t make available their wards for interrogation.

Olusegun added that all the students questioned told the police that the alleged beating never happened.

“There were four bunks of eight students in the deceased’s room and we were given all the names of the roommates. We succeeded in interrogating four out of the seven roommates. The parents said their children were going through trauma. Having not been able to interview the remaining, the investigation was not comprehensive,” Bamidele said.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, a document obtained by TheCable showed that, while the police were still probing the accused Dowen students, a Yaba chief magistrate was entertaining applications to secure bail for them from Boys Home in Oregun, a detention facility where they were ordered to stay for 21 days to prevent any interference with the probe.

In a protest letter addressed to the high court and signed on behalf of the commissioner of police, Fayoade Adegoke (DCP) said the situation came as a “rude shock” as the IPOs were working on a “fresh intelligence report” at the time.

The DCP subsequently asked that the bail be revoked, given the sensitive nature of the case, but this never happened.

On April 5, Benedict Agbo, a police toxicologist — while being cross-examined about the first autopsy’s claims of chemical poisoning — told Femi Falana, the human rights lawyer, that he received no request to test an “unknown black substance” found in the intestines of Oromoni during the second autopsy by LASUTH pathologist Sokunle Soyemi.

Advertisement

Agbo, who had worked with the SCID for 25 years, said the substance, believed to have contained evidence of the chemical alleged to have been forced down the throat of the schoolboy, was not released to him for examination.

CONFLICTING DPP VERDICTS

Advertisement

TheCable followed the coroner’s inquiry into Oromoni’s death — both at the magistrate court in Epe and when it moved to the Ikeja high court — and obtained the interim and final DPP advice on it. In its first advice dated December 30, the DPP couldn’t affirm allegations of murder, manslaughter, poisoning, and cultism against the students but it established criminal negligence by the school and five staff members for “disregarding” the reports of bullying made to them.

Section 252 of the Criminal Law prescribes a two-year sentence on convictions for “negligence causing harm”. In the final advice of January 4 based on the LASUTH autopsy establishing Oromoni died of organ failures triggered by an infection to his ankle injury sustained during a football match, the DPP cleared the students and staff members of culpability in the death case.

Advertisement

In an interim investigation report dated December 24, the police had established that there was an event in the past where the deceased was indeed bullied by one of the accused boys for refusing to describe his sister’s private part but the school authorities failed to give attention to the matter and punish the said student.

Another student of Dowen College had also been suspended in 2019 over his alleged involvement in the bullying and assaulting of a colleague who was later withdrawn from the school. One Omayeli Edemaeyan also revealed, with video evidence, that her son was in October 2021 attacked by five Dowen students, including one of the boys accused in the Oromoni case, but nothing was done about it.

Advertisement

The LASUTH autopsy addressed the “cause of death” but cleared the Dowen College staffers of the indictment on criminal negligence (for which they had earlier been arrested) on the basis of evidence that remains to be seen.

YAHAYA ALIYU: JUSTICE DENIED, FATHER STILL GRIEVES

Students protested. Police vowed to investigate. The Adamu Adamu-led education ministry waded in for its own fact-finding. The incident spurred public fury in August 2021 when 13-year-old Yahaya Aliyu of the Federal Government College (FGC) Kwali, in Kuje, Abuja died after he was flogged by his teacher Dorcas Gibson for failing to do his homework.

Aliyu, said to be the grandson of late Aliyu Mohammed, a former secretary to the government of the federation (SGF), was said to have been subjected to punishment and hit several times with a metal bucket handle despite complaining to his teacher that he was ill.

He would subsequently lay his head on his table in quietude after which his colleagues raised the alarm as his condition deteriorated.

Rushed to a hospital, the boy would later be confirmed dead. The school didn’t address the press on his death but it was reported that FGC Kwali claimed Aliyu died while on admission for cerebral malaria at Rhema Hospital in Kwali.

Musa Ibrahim, FGC Kwali alumni president, who had sought justice for the deceased, told TheCable over the phone in March 2022 that his team backed down after they were told the police were conducting an independent investigation.

“We did all we could. We can only seek justice, not investigate. They haven’t given any report since,” Ibrahim said.

When TheCable contacted Nuhu Aliyu, the deceased boy’s father, in February 2022, texts to his line were greeted with no response. Asked how the case wound up in a follow-up call days later, Nuhu’s voice began to tremble.

The bereaved father stated that this reporter’s words were bringing back “memories I’ve tried to put behind me”.

“I went there a lot of times. They even told me to stop coming there. And they will be trying to cover it up. I don’t want to talk about it anymore. I can’t keep doing this to myself. It’s depressing,” a grief-stricken Nuhu lamented.

Although he promised to open up on the matter, a call and a text message seeking further information two weeks later met outright rejection.

“I don’t want to be disrespectful. Don’t call again. Don’t go further on this,” he said in a tone signalling finality.

Contacted in March, the FCT police didn’t immediately volunteer information as regards the outcome of its probe.

In May 2022, Josephine Adeh, its PRO who assumed duty last September, maintained that she knew nothing of the case.

“It’s not something I can give a reply to when I didn’t know there was a case like that. I have to find out,” she said, hanging up the phone after she was asked when the FCT police would be able to give feedback on the matter.

CHIMDALU ONYEKWULUJE: LACK OF ‘MOBILISATION FEE’ STALLED PROBE

In the south-eastern state of Anambra, Chimdalu Onyekwuluje of St. Michael’s Boys College, Ọzụbulụ, Ekwusigo LGA was handed over to his father almost lifeless after the school mandated the 11-year-old to finish his examinations before it would consider releasing him to his family to seek medical care for his ailing health.

Cornelius Onyekwuluje alleged that his son, a boarding student, died on account of negligence by the school on December 17, 2021.

This, he said, was days after he eventually succeeded in picking up the boy from the school for medical treatment. In a petition addressed to the inspector-general of police, the family through its lawyer, O. C. Onwugbufor, alleged that Onyekwuluje had been sick but the school management neither informed his parents about his condition nor sent him to the hospital to seek proper treatment.

The petition said the father got wind of his son’s situation through another student who called his own mother to pass on the message. Cornelius informed TheCable that he immediately called the school management who told him not to bother as the boy was being cared for.

He said his informant was subsequently punished after he reached out again to alert him that his son was gravely ill and was only making it to the exam hall through his assistance.

On arriving at the boarding school, Cornelius said his son’s condition had degenerated so much so that he could barely talk, walk, or eat — and the school claimed they were just about to send for him before he arrived.

Cornelius also shared with TheCable the recording of a conversation with his son’s school guardian where the latter reassured him of the boy’s condition.

In his pursuit of the case, Cornelius said the police in Ukpo halted its probe after he couldn’t afford to pay ₦150,000 to enable the operatives to fuel their truck and drive down to Ọzụbulụ to investigate the case.

Through the infamous two-hour gridlock of Okposi, and past Anambra’s town of Ọba, this reporter visited St. Michael Boy’s College in sparsely populated Ọzụbulụ but its staff flatly refused to speak on the matter, arguing that it was “too sensitive”.

They added that only the principal, who they claimed was not on seat, could speak or approve a comment from the school on the case. TheCable sought an audience with the principal and vice-principal but the response was negative. Subsequent efforts to engage with the school were unsuccessful.

Calls and text messages to Romanus Ike Muoma, the principal, who is also a Catholic reverend, weren’t answered.

A staff who indulged this reporter in a short talk in his Igbo dialect said, with a smug smile, that the school had already put the matter behind and that the case had already “died down”.

With newspaper reports on his son, mortuary papers, and petitions tucked under his armpit, Onyekwuluje would later add: “After my son died, I had to withdraw my kids from boarding school so they’re educated under my supervision.

“I’ve been deeply traumatised ever since this happened. I’m an artisan. I haven’t been able to work for my clients at my full capacity. Did I do anything wrong by setting aside more than ₦500,000 to give my boy good education?”

IZUCHUKWU ONWUALU: FAMILY ALLEGES COVER UP

The ambience was tense; emotions were boiling over when this reporter visited the home of the Ọnwụalụs in Akpaka, where they also run a bar. An eerie silence had the vicinity in its chokehold. Izuchukwu Ọnwụalụ, an 11-year-old JSS 1 student at St. Valerian Catholic School, Onitsha, Anambra, had died after being flogged by a science teacher who was later identified as Chidịọgọ Ọbụnadike.

The mother of the deceased, evidently agitated by the situation, soon delved into a narrative outburst, alleging that the family was intimidated by the church-owned institution after its top officials and the clergy weighed in.

“The school had claimed to the public that my kid was already sick. But that’s a lie,” she said. “He’s been completely healthy and often manages our shop after school by himself when we’re away. It’s not supposed to be up to us to take up the case with the police. A human died. Police could have swung into action, even before we agreed we won’t press charges.”

Dubem, the deceased’s father, said he took his son to the school on January 11 but the boy was brought home at noon by his pre-teen friends — not by the school staff — with a report that a female teacher descended on him with slaps and whips of the cane for not doing his resumption test at the pace of his colleagues.

The father, his eyes bloodshot, said he had returned to meet his son writhing in pain, with his panicky wife pouring water on him to ease his pains. Dubem noted that his son’s friends, who had witnessed what transpired in the class, said while being flogged, Ọnwụalụ broke loose and hit his head against the concrete wall.

Ọnwụalụ’s classmates said the boy was compelled to write the test and he subsequently complained of a headache. It was said that he was rushed to the school clinic, after which he was carried home due to the non-availability of healthcare personnel.

“His eyes were twitching and rolling upwards like he was losing consciousness. One of the boys who brought him home said he himself was slapped when he exclaimed at the heavy flogging. They said my son was taken to another room where no one knew what was done to him before he started vomiting when it was closing time,” Dubem said.

The father said he took his boy to the family nurse who directed them to Waterside Hospital in Onitsha from where they were referred to Borromeo Specialist Hospital where the late boy was put on drips. He said the doctor subsequently directed them to Nnewi Teaching Hospital.

“We were given a medical note. I called the school but they weren’t reachable. At Nnewi, the doctor said he couldn’t handle him. I kept the school posted. We went to New Hope Hospital in Onitsha where he was confirmed dead.”

In the said medical note, a neurosurgeon at Borromeo wrote that the deceased had been brought into the facility unconscious and added that there was an “associated seizure” which was taken for a case of “traumatic head injury”.

The doctor further wrote that the family reported that the deceased was also hit on the head with a “water-filled bottle”.

BURIAL WITHOUT AUTOPSY, POLICE MEDIATION INCONCLUSIVE

Ezeanyi Victor, the priest of the church within which the school is erected, had facilitated the burial of the boy.

Dubem said Ezeanyi promised to look into the matter but the school continued to shield the identity of the teacher. The father said he was opposed to putting his son in the mortuary while they went back and forth with the police. Hence he initiated burial talks on January 12, while still planning to unravel the situation surrounding the death.

“The reverend gave us ₦200,000 to foot burial bills and said he would call a meeting to discuss the case but it never happened. I called days later and mentioned the teacher but he retorted I shouldn’t ask him that question. He said the teacher travelled and we would have to wait on her return. The case later got to social media,” the father said.

Dubem said the police would later call him after the bishop contacted the commissioner of police who later invited all parties for interrogation.

He said the teacher told the police that the deceased was climbing desks and sticking his hands into the ceiling fan which prompted her to flog him and hit him with an “empty water bottle”.

Dubem said the reverend argued to the police that the school won’t compensate or officially apologise but would pay the family a condolence visit.

He said the reverend opposed requests to see the teacher’s face as she came to the police station masked, with a baby strapped to her torso. He said the teacher also refused to apologise until prodded.

“Painful is that neither the teacher nor her husband has come to own up. At the school’s PTA meeting, some staff even lied that my son had always been a sickler. But he was healthy. You can ask neighbours,” Dubem gestured.

After refusing to take the blame in the matter, the school agreed in the presence of the police to pay a condolence visit to the parents of the deceased where they were to detail the findings of an internal probe conducted on the case and possibly pay monetary compensation to the family.

According to Dubem, he had contacted the police area command days later to state that the school had yet to act in accordance with what was agreed during the meeting at the station — but the family was told to be patient.

Findings revealed that police intervention in the case didn’t go beyond inviting the bereaved parents, their family members, and staff of the school for questioning.

Anthony Ikenga, spokesperson of the state police command, who had in January promised to take up the matter when it caused public outrage, maintained that he had no knowledge of the case when contacted by TheCable in March.

SCHOOL MAINTAINS INNOCENCE

St. Valerian Catholic School is situated in Akpaka GRA 2, a predominantly residential area marked for its dirt roads, sand mining operations en route to its gate, and a slaughter site where the singeing of goats in an open fire fuelled by scrap tyres has left the soil black.

At the main gate, which had the church’s name emblazoned on it in brick letters, multiple buildings can be spotted in the distance, including the chapel, the reverend’s house, the classroom block, and structures still under construction.

Kids to be picked up playfully loitered around, chit-chatting in front of the chapel where a signpost read “silence zone”.

TheCable sought an audience with the principal but an official, who denied this reporter access due to “tension in the school”, argued that only the priest could speak on the matter.

This reporter later approached the priest on the evening of the next day but he would cite the family’s “outright lies” as the reason the school bottled up.

He argued that “nothing major happened” and added that he was told that the bottle with which the teacher hit the boy was empty. The priest denied the boy was severely hit, saying he was only “patted” from behind with a tiny whip.

“His father and I discussed it on phone until 11 pm. I called the teacher and principal. I understood that we did no wrong. They denied smashing his head against the wall. They couldn’t have. He wrote a second test after,” he said.

“It wasn’t I who suggested the burial. The boy’s father did. In Igbo tradition, you can’t possibly bury the dead in a hurried manner. We had nothing to cover up. It was because of social media stories we decided to shun the press.”

‘SEIZURE, VOMITING POINT TO INTRACRANIAL INJURY’

Goke Akinrogunde, chairman of the medical negligence committee of the Nigeria Medical Association (NMA), said the symptoms exhibited by the boy point to an intracranial injury that would have required an emergency craniotomy.

“The major culprit might not be the plastic bottle. That child must have been hit heavily on the head or maybe, in the course of the beating, hit his head. All the symptoms he had exhibited are pointing to an intracranial pressure which means that pressure from inside the head gets higher than usual because of a lesion or a bleeder,” the doctor said.

“Blood won’t burst out of the cranium when a patient bleeds in the head. The mechanism would be to compress the brain tissue, hence the pressure. [Impairment in] the brain stem is why you have controlled vomiting and seizure.”

The doctor, who said the preliminary diagnosis was “sound”, pointed out that exhuming the body and conducting an autopsy would most likely reveal blood clotting in the skull of the deceased.

“If they want justice, an autopsy should be done. It’s obvious that it’s beyond the plastic bottle,” Akinrogunde said.

“Even the skull of a day-old baby is strong enough to withstand being hit with a plastic bottle. It’s also possible that a bleeder occurred at that time. This is because there are fragile brain tissues some of us carried about from birth. They are called berry aneurysms, where any little trigger can just rupture the affected blood vessel to cause a bleeder.”

LAWYER GIVES OUTLOOK FOR PROSECUTION

Adeola Adedipe, a legal expert, argued that police operatives in any functional criminal justice system are meant to independently investigate homicide cases as they can cause a breakdown of law and order in that immediate society.

“They’d have to exhume the body and go for a series of tests. But we have many limitations in Nigeria. Someone has to drive it. Police investigations are capital intensive. In developed climes, that is not the case. They have a system that works. Here, a policeman can hardly even fuel his own vehicle when they have emergency operations,” he said.

“It’s no justification but these are practical limitations Nigeria suffers. Furthermore, if there’s no complainant, it becomes more difficult, even if an NGO were to sponsor the legal costs to be incurred. Once there’s a homicide, it is the duty of the state to thoroughly investigate. It’s a criminal charge that should be pressed in the name of the state.”

Adedipe stated that the circumstances surrounding the death of young Ọnwụalụ points to “culpable homicide”.

“There are proximate and remote causes in death cases. Preferring a charge would require sound medical analysis and an autopsy. There’s culpable homicide with the intention of causing grievous bodily harm,” the lawyer added.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment