Define Irony: Nigeria’s politicians speedily considering the tripling of a Diaspora Bond but dithering for years over the Diaspora Vote.

On January 21, 2014, the presidency wrote to the national assembly seeking to increase the $100 million Diaspora Bond they earlier approved to $300 million.

Exactly a week later, Dr. Baba Ahmed of the US-based Nigerian Diaspora Electoral Reform Group emailed the house committee on Diaspora affairs, copying prominent politicians. The message was brief: “With the 2015 elections season around the corner, we are hereby requesting the national assembly to include the million of Nigerians Diaspora exercise their God-given franchise rights to vote in the upcoming elections through the revisions / amendments to the Electoral Acts of 2010.”

But by April 2014, while Nigeria picked advisers for its Diaspora Bond and the World Bank revealed our country is the largest recipient of foreign remittances in Africa, with $21 billion sent from Nigerians living abroad in 2013 alone…INEC chairman Attahiru Jega was effectively asking us to kiss the Diaspora Vote in the 2015 elections goodbye. Until the Electoral Act is amended.

Advertisement

Ahead of next year’s elections in Africa’s largest economy, its citizens abroad remain disenfranchised. While the rest of the electorate grapples with the mechanics of voting, it is time Nigerians abroad understood and —where applicable — relayed the following:

The onus is on us to educate (and lobby) our lawmakers

Granted, in the last days of June, delegates at the Sovereign National Conference “agreed that the constitution should be amended to enable Diaspora voting”. But before we break into song and dance, we must remember this is not an absolute guarantee. For one, these things take time.

Advertisement

Nigerians seeking the Diaspora Vote must also understand this is no longer about INEC or the presidency, and all about lawmakers. Unless we increase our efforts, the Diaspora Vote could remain a tool, touted as empty promises in party manifestos or used to placate audiences when politicians visit to canvass support — whilst being treated as a nuisance in legislative chambers. Despite the work of sponsors including Honourable Abike Dabiri-Erewa on The Electoral Act (Amendment) Bill, deliberations to allow external voting were suspended in 2011 over the most retarded of excuses. Even more unfortunate was that this never got debated extensively. This situation can recur and because the vote is beyond important, we must stomach these excuses long enough to explore — and publicise — counter-arguments, with tested case studies.

Costs and logistics

You begin to realise how ridiculous these excuses sound when you note that countries like Rwanda (with an economy less than 2% of Nigeria’s $510bn) and South Africa have found a way to run the Diaspora Vote. Rwanda’s expats voted in the 2013 parliamentary elections, a notably tricky venture even developed countries do not take on, given the different ballot papers needed. Surely Nigeria, with the world’s highest-paid lawmakers can’t find the money to foot these costs? What costs exactly, when Nigeria already has embassies worldwide and flies passports and diplomatic bags already as a matter of fact? What, an additional 100,000 ballot papers will weigh too much? Rwanda was able to achieve the external vote by its 3rd democratic elections, South Africa by its 5th while Nigerians are being told there will be no external voting in what is also its 5th democratic election?

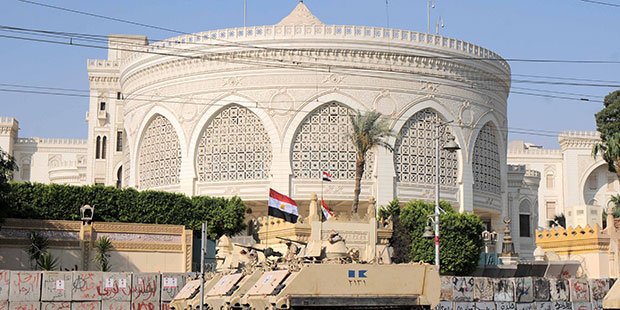

Recent precedents on the continent puncture holes in these arguments that shun an extensive debate on external voting. Months before the May 2014 elections, South Africans abroadregistered at their country’s embassies over four weeks. The diplomatic posts opened for two weekends to allow full-time workers register. Diaspora voters then had until March 12 to notify the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) of their intention to vote. Even though Google exists, it is up to Nigerians abroad who care to educate our lawmakers on the easily accessible fact that generally, external votes are usually cast earlier, to allow efficient transfer and counting of ballot papers. South Africans abroad voted a whole week before their counterparts at home. Egyptians cast their vote in key embassies. In Rwanda more polling stations were set up in countries like South Africa, where there was a large number of voters on the electoral roll signifying an interest to vote. In fact, South Africa’s electoral commission assisted Rwanda with voting booths and security. Where there is a will, there must be a way. Political will, that is.

Advertisement

INEC’s failures

Saying INEC is inefficient at home and so cannot handle external voting abroad cannot wash in a globalised world, because every electoral process is subject to fraud. In the UK, since 2001, anyone on the voters’ register can apply to vote by post. Some 1,500 votes were illegally cast in the western central area of Birmingham in 2004, resulting in the voiding of 6 Labour seats, the presiding judge saying the level of rigging “would disgrace a banana republic”. Presently, authorities are investigating 16 areas over electoral fraud, with the electoral commission at some point considering a blanket ban on postal voting in these areas. But they haven’t banned voting entirely, because it comes with the territory. Rather, nations continue to work on the kinks in the process, and set punitive measures for criminals who tamper with it. What stops Nigeria from adopting the party agent and/or the independent election observer models to monitor the votes abroad?

We need to tell our lawmakers in the strongest possible terms that the presupposition of manipulation is not a strong-enough reason to deny or delay the Diaspora Vote. Even an actual manipulation of the election is not a reason to infringe on expats’ human rights to vote. After all, even with the shenanigans at home, elections still go on in Nigeria.

So…try the other one.

Advertisement

Forget remittances, try Democracy instead

In educating our lawmakers and holding them accountable, we must stop shoving remittances in their faces. Why? Because democracy is reason enough for the Diaspora Vote, whether we send money home or not, whether the embassies know exactly how many Nigerians live abroad or not. If we are operating a democracy then there should be no half measures. South Africa is not called “Africa’s most sophisticated economy” for nothing, because despite knowing that the Diaspora Vote would not be a swing vote, it nevertheless ensured “108 flights carried ballot papers, boxes, pens, seals and other material to South African missions across six continents”.

Advertisement

The message was clear: So what, if of 100,000 estimated citizens in the UK, only 9,863 turned up to vote? Or that only one South African voted from Guinea Bissau? The South Africa government duly relayed that single vote back home.

So it is up to Nigerians abroad to make our lawmakers understand that yes, external voting may cost more per voter; but under a true democracy, it is not negotiable. Statements like: “Why don’t they just pass the Bill and let us fund it from the Diaspora,” credited to a president of the Nigerian Women in Diaspora Leadership Forum are weak, and lessen the importance and sanctity of our right to vote. When the Diaspora Vote is granted, it should be the full responsibility of the state, as seen the world over.

Advertisement

Be flexible, realistic and lucid — learn from Kenya’s Diaspora

A Diaspora Vote is not negotiable, but its parameters certainly are. For instance, German law states that diaspora voters must have been resident in Germany for an uninterrupted period of at least three months, aged 14 and above. This stay must not date back more than 25 years. Expressly, Germany also says to vote from abroad, citizens must “have become familiar, personally and directly, with the political situation in the Federal Republic of Germany and are affected by it”.

Advertisement

South Africa’s was forced via a court case, and Nigerians abroad also admirably kicked off this campaign in court. But beyond amendments of sections of the constitution, we must now simultaneously seek debate and delineation of the finer points: How can we vote — by post, by proxy, electronically or in person? We must begin to iron out all these issues in time because despite the valiant efforts of Kenyans abroad who were also backed by the courts, external voting for the 2013 general election was whittled down to the neighbouring countries of Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda. One main factor was that on November 15, 2012, just months to the elections, a court ruled that: “the right of Kenyans abroad to vote was not absolute but subject to reasons and restrictions”. Following an appeal, the electoral authorities have been directed to ensure preparedness towards full external voting in the 2017 elections.

This leads us to the fact that Nigerians living abroad need to be better organised, with fully-updated websites, co-ordination across continents and political party lines, as well as a willingness to actively seek the input of the younger generation. If the Confab delegates’ wish is granted, then a Nigerian-Diaspora Commission will be created and we must be ready to work in and with it as a coherent, whole force.

So it isn’t enough to keep calling ourselves “the 37th state of Nigeria” all over cyberspace and describing remittance figures as “internally-generated revenue” by this 37th state when there is no cohesive, lasting structure. We have to be ready to negotiate with one voice: are we open to a regional Diaspora Vote as a preliminary test, as seen in Kenya? Are we prepared to meet the government halfway regarding costs, as seen in Mozambique’s 2004 general elections, where external voting took place only in countries where there was a minimum of 1,000 legally-settled citizens? Have we considered that Senegal’s 2000 presidential elections operated under specific legal provisions that restricted external voting to only countries where at least 500 Senegalese expats had signified a willingness to vote? Are there other new restrictions that need to be factored into the constitution, or new specific powers that need to be bestowed on INEC? Now is the time to bring them to the table once and for all.

Be prepared to once again return to Nigeria to vote

I wager that even with the recommendations of the Confab, 2015 is out of the equation. We have to be in this for the long haul, because the fact is that most politicians in Africa are afraid of the Diaspora Vote, never mind it has never been scientifically proven to be widely influential. There’s Eritrea, which notably allowed external voting in 1993 towards a referendum for its Independence, yet has blocked the Diaspora Vote since. Look at Zimbabwe as well, where its citizens abroad are campaigning for “the restoration of their voting rights to be a pre-condition for any more re-engagement between the European Union (EU) and ZANU PF”.

Incumbent parties on our continent always claim the opposition will spread propaganda to win elections using external votes, while the opposition parties will always say the Incumbents will rig the ballot if totally entrusted with handling the logistics via embassies. And so, while we hope for the best, we must at least factor in the eventuality of any government of the day deciding to pull rank. We must prepare to explore our legal options and expand the scope and quality of our lobbying, because while we grapple with the basic right to cast a vote, French-speaking Africa is already allocating parliamentary seats to their citizens abroad. Cape Verde’s constitution gives 6 out of 72 seats; Algeria’s is 8 of 389 seats and Angola allocates 3 out of 220 seats.

So, fellow Nigerians abroad, as you can see, we have our work cut out if we ever hope to achieve a Diaspora Vote that is not just on the constitution, but actionable by 2019.

Let’s get to it, please.