National budgets are not like household budgets, where families try to balance their expenditure with their income. Technically, in macroeconomics, countries could spend more than they earn. But there is a caveat: such extra spending should be on investments – capital projects.

The harmonized 2017 budget proposal by the parliament—which would be sent for presidential assent in the coming days — shows that Nigeria has no regard for this caveat.

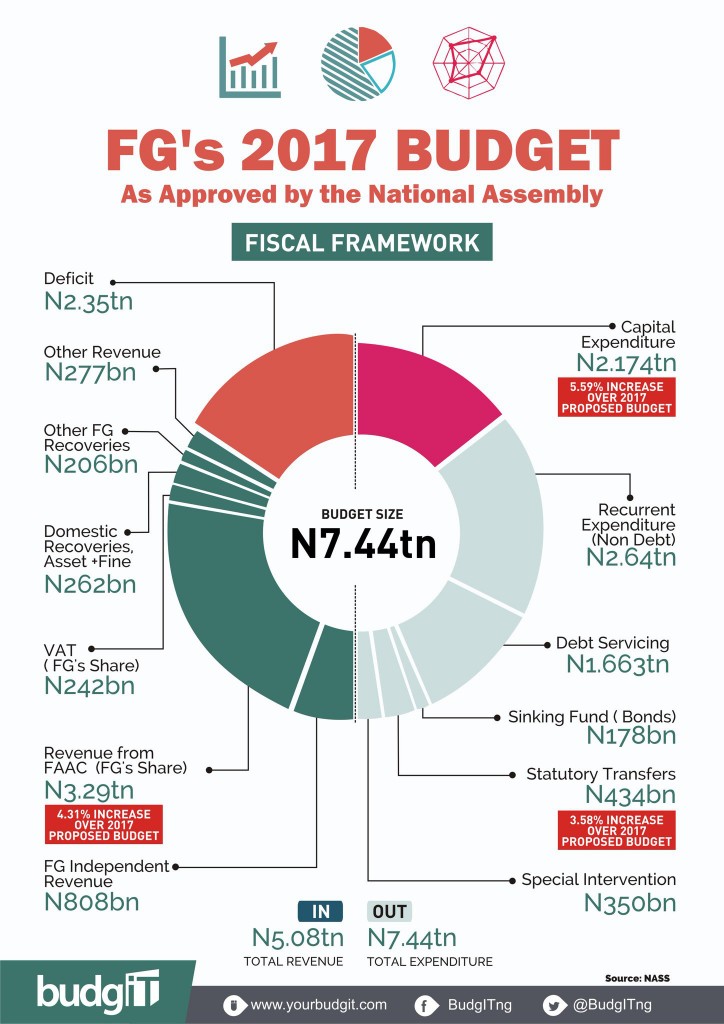

This year, Nigeria proposes to spend N7.44 trillion. In this proposal, the country expects to earn N5.08 trillion, but plans to spend N5.265 trillion on recurrent expenditure, including servicing loans. (The budget deficit is N7.44 trillion minus N5.08 trillion, which is N2.36 trillion).

The 2017 budget deficit would have been more pronounced had the national assembly not jacked up the $42.5/ barrel oil bench mark proposed by the executive to $44/barrel.

Advertisement

Despite this optimistic revenue profile, in 2017, Nigeria will continue the culture of borrowing to sustain its recurrent expenditure, such as paying salaries. And it doesn’t stop here: Every kobo the country is going to spend on its N2.174 trillion capital expenditure, in 2017, would be borrowed, as well.

What does this mean? It simply means that all the proceeds from the country’s oil resources, which ought to belong to this generation and future generations, is being spent by this generation on recurrent expenditure. Nothing is kept for the future – for your children’s children.

Advertisement

On the surface, since spending on infrastructure is a form of investment, Nigeria seems to be doing the right thing by spending a large chunk of borrowed money, in the 2017 budget, on infrastructure.

But about 46 percent of this borrowed money is expected to come from abroad, with an average interest rate of over 7 percent plus possible foreign exchange risks. And question is would this investment on infrastructure yield returns of over 7 percent, in the short to medium term? This is very unlikely.

Had oil prices not rebounded, the immediate economic impact of Nigeria’s 1.8 trillion capital investment in 2016 – which has had about N1.2 trillion released – would not have gone anywhere close to taking the country out of recession.

With high interest rates, it is always advisable to make investments with savings. The country’s $1.5 billion savings in the Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) is nothing compared to what a population of over 150 million people should have.

Advertisement

The Future Generation Fund of the NSIA is actually aimed at guaranteeing that generations yet unborn would have something to fall back on should the oil market collapse. But Nigeria doesn’t seem to think of its unborn kids.

By jacking up the budget’s oil bench mark to $44/barrel from $42.5/barrel, the national assembly has reduced the amount that Nigeria could save and subsequently invest through the NSIA.

Going forward, Nigeria has to cut its recurrent expenditure and increase its investments in NSIA. Cutting recurrent isn’t easy, but it’s important to start thinking of the future of our unborn children.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Add a comment