BY OSHO SAMUEL

For every prestigious institution of higher learning, it is a commendable feat to exude uniqueness in the execution of plans but not all signs of distinction connote outstanding excellence. In institutions where policies are implemented to frustrate the efforts of students, there is a threat to the dimensions of intellectual engagement possible in such climes.

I was shocked and unduly flustered when the grading system of the Nigerian Law School (NLS) was explained to me by a close friend, Joseph Onele, a solicitor and advocate of the Supreme Court of Nigeria as well as a first-class graduate of Law from the University of Ibadan. This is an attempt to lend my voice to a cause that is seeking a change in the present grading system used in the Nigerian Law School.

Barely 14 years after the establishment of Nigeria’s premier university, University of Ibadan, there was a need to provide a judicious legal education within the precincts of the Nigerian Law to foreign-trained lawyers and aspiring legal practitioners in Nigeria, hence the creation of the NLS. The curriculum of the educational institution is geared towards delivering a robust practical experience to the potential members of the Nigerian Body of Benchers. In 1963, the operations of NLS started on an excellent note.

Advertisement

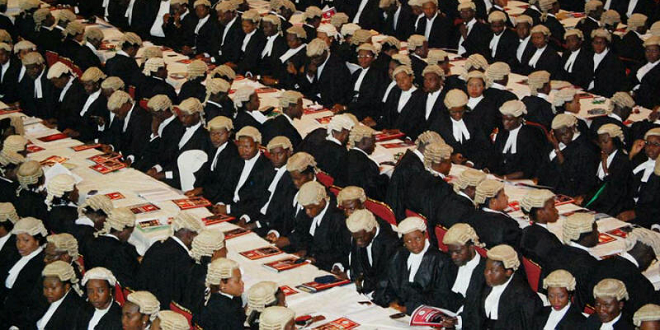

However, over the years, there has been a torrent of accusations and complaints concerning the marking scheme and grading system of the NLS. Often times, these complaints gain a measure of attention as a result of the mass failures that are usually recorded in the NLS Bar final examinations. During the course of their stay in NLS, students are exposed to best practices and a curriculum of high standard which comprises of five courses: Criminal litigation, Civil litigation, Property law, Corporate law and Professional Ethics. To the students, facing the Bar examinations is dreadful and it is like passing through fire.

It is a common knowledge that grades are of great essence in any educational adventure. The marking scheme and the grading system of any educational institution are the two basic elements that define the grades of students. In a system that has a strong predilection for grades over competence, getting a poor grade is a bad omen for career pursuits. The distinctive grading system employed by the Council of Legal Education in NLS is amusing and sadistic.

In the NLS, the final grades of students are based on their lowest grades. For instance, if a student amasses 4 As and 1 C, his final grade will be a Pass solely based on the “C.” The student is graded based on his lowest grade, 1 C, which is a vicious scale for the assessment of competency in students. If a student has 4 As and 1 B, it implies that his final grade will be a Second Class lower (2:2). This is arrant nonsense and an absolute manifestation of cruelty in a place that is dedicated to upholding the tenets of fairness and justice.

Advertisement

If the Council of Legal Education continues to use this grading system in a bid to pride itself in an eerie form of revered rarity, it should be reminded that this caustic system has no regard for the future of students. It is simply illogical. A student studies hard enough to get distinctions in Criminal litigation, Civil litigation, Professional Ethics and Property Law but managed to record a B-grade in Corporate Law and ends up with a 2:2 final grade, how can the understanding of the four subjects be based on the performance recorded in the fifth subject? It is synonymous to grading students enrolled in a five-year course based only on their final year results – discard the first four years and focus on the final year to determine their graduating Cumulative Grade Point Average. This basis for judging competencies is flawed, harsh and retrogressive; it negates the creeds of common-sense.

I can completely relate with the tension that grips the six Law School campuses when students are preparing for Bar Finals, it is a reflection of a community that is under intense stress to deliver grades that must not be less than a distinction. There is anxiety over marks and less focus is given to intellectual engagement, transmission of ideas, interactive discourses and rigorous digestion of course modules because all that matters, in the end, is the ultimate grade. For many students with excellent grades from their respective universities, this is the time to prove their worth and strengthen the life of their dreams. It is a call that has a plethora of demands and just one careless grade in one of the five subjects can decimate assiduous efforts sown in studying and preparation.

In the eyes of reasoning, the brutal grading system can be interpreted as a sign of weakness and insecurity on the part of the NLS. It purportedly projects silent skepticism in the standards of the intellectual property that is administered to the students. Unexpectedly, asides the final grade, students are not privy to a detailed breakdown of their results. Suddenly, results have morphed into the clandestine assets of the institution; some students only get to see the details when their employers demand their transcripts from NLS. It is believed that the NLS is averse to narratives embellished with success stories of students in Bar Final exams. Every year turns out to give endless tales of an ego battle that ends up with the system triumphing over the students. There are beliefs that the sacred institution for upcoming Nigerian legal practitioners is wired to bring intellectual giants to their knees and make students know that the expedition to the Nigerian Bar is a tempestuous one.

It is worthy to note that before the establishment of the NLS, practicing lawyers in Nigeria received legal training in England and were called to the English Bar. It will be laudable to draw comparisons from the grading systems used in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. Most of the prominent law schools in the United States use the pass/fail system and this includes Harvard, Stanford, Berkeley, Yale and much more. Other universities like the University of Kentucky’s Faculty of Law use the GPA and class rank distribution system. This grading system assists the students in reducing the stress and anxiety on marks while there is focus on fostering qualitative education and productive learning. In the Faculty of Law at the University of Toronto, grades are assigned to students based on their cumulative grade point average with the possibility of falling into one of the five available categories: High Honours, Honours, Pass with Merit, Low Pass, and Fail. These are reputable educational institutions with a proven record of churning out highly competent Barristers and Solicitors. And yet no one sheds a tear about their grading system.

Advertisement

In the midst of criticisms of the grading system, it is safe to pontificate the principles of fairness, justice, and equity. In a sane environment, making an overhaul or a review of the existing grading system will yield bountiful results both for the students and lecturers. That’s assuming that these are lecturers who smile with glee when they see their students succeed and not sadists who are interested in seeing more students fail. Above all, this only reinforces the strength of a philosophical notion which opines that marks and grades are deficient evaluators of quality, competence and excellence.

5 comments

if I had been privy to this information before my sojourn as a law student,I’m in no doubt that I would have made an alternative choice.been a lawyer isn’t worth the stress I tell you. as a 400level student,I’m already in a quagmire as to what my fate will be at the NLS.it’s disconcerting to say the least.

That grading system is crap. It’s like Nigeria has been left behind by other countries. How can a country allow this? How?

The grading system is seriously unfair, to be honest Law School is very frustrating. Recently, a couple of resit students where denied writing their resit examination last week as a result of not meeting the attendance requirement. i personally think that was a very wicked approach to the matter at hand. This is because, most of these resit students are being forced to attend lectures for modules which they had earlier passed. For those of you who do not know, If a student fails one paper, he has a conditional pass and can only do that paper but where he fails more than one for instance 2 papers or more, he is forced to do all the papers again, including those he passed and forced to attend lectures. Now, is that really a fair approach my fellow Nigerians? The legal system is supposed to be based on fairness but these decisions negates that.

Moreso, the resit students who were hugely affected were mostly from Lagos Campus. It was bad enough that exams where moved to Abuja after most of them had paid to do it in Lagos campus and also made further arrangements in Abuja such as accommodation, flight tickets etc

Only to be denied writing the exams after all preparations. Is that really fair or should we call that justice?

I was also informed by my friend who was affected by that decision that the secretary to the council had told them to apply for a refund but that they may not get the monies back or apply to defer the payment to next year April 2018 as they would not be allowed to write the exams with the regular students in august/September. Is that not wickedness? Decisions like that can drive one into depression and suicide

Why are we wicked to ourselves in this country, this is so sad. Please lets forward this message round so someone higher in authority will reverse that wicked decision

Thank you

We need an urgent response, a full explanation from the Institution of either a rebuttal or a confirmation of Osho’s write up.

thankgod every thing has change, am on my coming.