Children at Garin-Gambo village, Gumel LGA

This report was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

Nothing is as devastating as when one’s little child wakes up from bed one morning and says: “Mummy, I can’t hear you. I can’t hear my sisters too. It seems my ears are no longer working.” The palpable fear. Then begins the running from pillar to post.

That was the situation Hafsatu, a 27-year-old mother of six children, found herself in August 2022 when Farida, her eight-year-old daughter, woke up with a hearing loss. It was totally unbelievable.

In the afternoon of the previous day, the child had run some errands; by night, she became sick. She started screaming; next, she had a seizure and then a fever. The next morning, it was deafness. For a beautiful black girl without any form of deformity from birth, what could have happened overnight, everyone questioned? Sadness descended on the family and tears flowed uncontrollably, but they held on to hope.

Advertisement

Hafsatu packed a few things and hopped Farida into a motorcycle to the car park in Maigatari, a border town in the Sahel of Jigawa state, Nigeria’s north-west zone. The sleepy agrarian community shares a border with the Niger Republic, a neighbouring West African country.

The journey of 145 kilometres from Maigatari to the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, in nearby Kano state, seemed like forever. After some laboratory tests were carried out, Farida was diagnosed with cerebrospinal meningitis (CSM), an acute infection and inflammation of the fluid and membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. It’s often preceded by symptoms such as headache, nausea, fever and a stiff neck.

Hafsatu said the doctors issued some prescriptions and she was asked to return to the hospital after a few weeks. But due to financial challenges, she could not afford the medicines and did not bother to return to the teaching hospital. Although Farida can still speak clearly in her native Hausa language, she now lives with permanent deafness and can no longer cope in the classroom.

Advertisement

“She’s in Primary 3 and still going to school, but she can’t hear anything the teacher says. We can’t leave her at home because she wants to go to school like her peers. So, she just goes and comes back without learning anything,” Hafsatu said.

“We communicate with her through gestures. Sometimes, she understands; other times, she doesn’t. She used to be playful and talkative, now she keeps more to herself.”

What makes Farida’s case more pathetic is that she wants education at all costs, but that can no longer happen in a regular classroom. Sadly, there is no school for special children nearby.

On the other hand, five-year-old Umma Mukhtar from Danyarda village in Sule Tankarkar LGA in Jigawa was not enrolled in school when she contracted CSM in March. According to Idris Haruna, the village head, out of about 20 people that contracted the disease during the outbreak that month, five children who were below the age of 10 died. Others were left with some form of deformity.

Advertisement

Ishake Mukhtar, Umma’s father, said she started having a headache; then it graduated to fever and later weakness of the body. He quickly rushed her to a hospital, yet her condition did not improve. She became deaf and irrational.

“The disease affected her brain. Now, she picks a fight with everyone without any provocation. We’ve cried and cried. I’m not happy with her condition,” the father of nine children sighed, dragging the quiet little girl to himself.

WHEN FATHERS CRIED

While Hafsatu and Ishake believe that one day their children will be able to hear their voices again, Babandi from Danyarda village is still inconsolable over the sudden death of his 15-year-old son, Bashari. He said he doesn’t wish any parent experiences the sorrow he passed through when his son died right in his presence and he had to bury him.

Advertisement

“He told us he was having a severe headache. Also, he complained of leg pain. Just one hour after, he died,” Babandi stammered. “Right here at home before me and his mother. We were helpless. We cried our hearts out. Later, the health officials told us it was meningitis.”

Occasionally, when the thought of how his child died crosses his mind, Babandi sheds a tear, wishing he was able to save the boy’s life

Advertisement

Usaini Abdulqudus, the Chief Imam of Garin-Gambo Village in Gumel LGA of the state, also functions as the chief consoler of the community by virtue of his role as the religious leader. Little did he know that the monster wreaking havoc on the village would knock on his door and snatch one of his eleven children. The CSM outbreak in the community took the life of his 14-year-old brilliant son, Abubakar.

Abubakar, who was the captain of his class, started exhibiting the symptom of the disease on a Friday evening and he was immediately rushed to the hospital eight kilometres away. On Sunday morning, he was declared dead. Usaini betrayed emotions, leaned on the floor and cried.

Advertisement

“He gave up in my presence. He was a very good boy. He told me to ask his friends for forgiveness and sell my motorcycle to offset the debt he owed them,” Usaini lamented.

‘A SLAUGHTER SLAB’

Advertisement

At Bekarya Village in Gumel LGA, it was the same melancholic tale. During the CSM outbreak in March, the community lost ten children – six boys, four girls — all of them below the age of 10. Most of them were out of school. It was a period of mourning and most households felt the pangs of death. To date, no immunisation exercise has been carried out in the village.

Children in Garin-Gambo Village too have not been immunised from the disease after it killed nine children and two adults in March.

In 2022, the media reported that at least 65 children in 14 LGAs in Jigawa died due to complications from meningitis, while most survivors were battling permanent deformities such as deafness, loss of sight, brain disorder and loss of limbs, among others.

In February, 38 persons, mostly children were reported to have died of meningitis in the state.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), meningitis is a devastating disease and remains a major public health challenge which affects mostly children more than adults.

In its latest data on Nigeria, the global health body said between October 1, 2022, and April 16, 2023, the country reported a total of 1,686 suspected cases of meningitis, including 124 deaths, while the highest proportion of reported cases was among children aged 1 to 15 years.

In Nigeria, Jigawa is the epicentre of the disease with 74% (1,252) of all suspected cases and 66 deaths. This was attributed to the state sharing a border with the Zinder region in Niger Republic where a CSM outbreak began in October 2022.

Lawan Rabiu, the Disease Surveillance Notification Officer (DSNO) for Sule Tankankar LGA, said the outbreak spread to Jigawa through Garin-Mu’azu, a border village, as a result of trans-border trade with the Niger Republic. With 27 LGAs in the state, 22 of them have reported cases of the disease, according to the state health ministry.

VACCINE SHORTAGE AMID AN EPIDEMIC

The WHO classifies meningitis into 12 serogroups out of which six (A, B, C, W, X and Y types) can cause epidemics.

“Because of environmental factors, the disease mutates. When we had the first outbreak of meningitis, it was type A. We did a massive vaccination campaign for type A and it reduced. When the recent outbreak happened, we went to the lab and discovered it was type C. It was more virulent. The vaccine for type C was not in the country then. It normally takes months for the shipment to get into the country,” Hassan Shuaib, the state immunisation officer, said.

According to Abdulsalami Nasidi, a professor and pioneer chief executive officer of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), CSM can be prevented through vaccines and health education.

“Meningitis vaccine availability in Nigeria is far from adequate to vaccinate all those living in endemic states of the country,” Nasidi said.

Jigawa got 272,000 doses of type C vaccine and began immunisation on March 28, targeting individuals between the ages of 1 to 24 years in 18 political wards. The doses have now been exhausted.

“We are still amid an outbreak. Recent cases are coming from the political wards that we did not reach. We reported 12 cases this week. The highest point was in week 15 of 2023 with 193 cases. There’s a shortage of CSM vaccines at the moment. We rested type A because we got the vaccine. We had just one case of type X and she was treated. We are making efforts to get more vaccines through the International Coordination Group (ICG),” Ishmail Mahmood, the state epidemiologist, said.

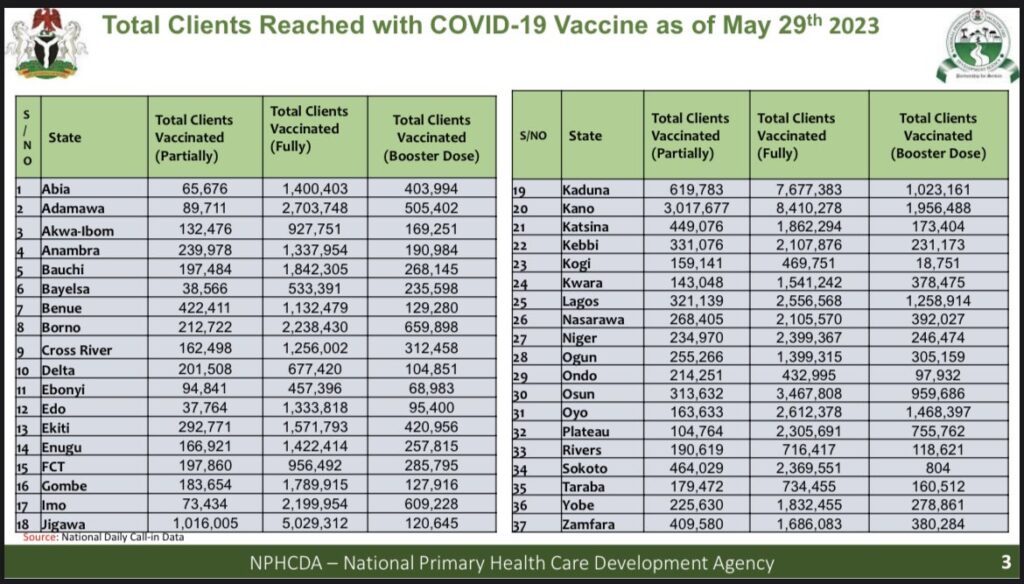

While the state is battling with a low vaccine shortage amid a meningitis epidemic decimating its young population, it has recorded a high success rate with COVID-19 vaccination. The latest data from the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) shows that over five million residents of the state are fully vaccinated for COVID-19. It occupies the third position behind Kano and Kaduna with 8 million and 7 million fully vaccinated residents, respectively.

On how the state was able to achieve much success with COVID-19 vaccination, Mahmood said the health ministry received adequate financial support from the state government and vaccines were readily available. He added that the establishment of a molecular laboratory in the state in 2020 was a big plus.

“It was a difficult time and it was overwhelming. COVID caused panic. It was a global crisis and it put all other diseases in the guardroom. Nobody really cared about other diseases. We all concentrated on COVID. There were other indigenous diseases like measles, pertussis and cholera, but the states were left to cater for them as most financial resources were for COVID,” Mahmood said.

OFFICIALS: HOW WE ACHIEVED IMPRESSIVE TURNOUT FOR COVID VACCINATION

Jigawa recorded its index case of COVID-19 on April 16, 2020. Officials confirmed that the state had 669 confirmed COVID-19 cases, while 18 died from the disease.

“The governor was the first person to be vaccinated. He said we should start with him. The governor went to his LGA to launch the COVID vaccination. We had Astrazeneca for phase one and two, later Moderna and Pfizer vaccines,” Shuaib said.

“We had an operation room where LGAs submitted reports daily. We had virtual meetings every day with LGA teams. We discussed challenges and solutions. The governor was getting the vaccination report every day and then phones the weak LGAs to do better. They got motivated. There was also a reward mechanism, an award for the five best-performing LGAs and also for the best team in each LGA.

“The traditional rulers also showed commitment. They got vaccinated. The governor asked the LGA chairmen to supervise vaccination and also instructed the head of the civil service to issue an immunisation mandate for all civil servants to be vaccinated. We went across the state to sensitise people. We did jingles on the radio; the radio programme made room for vaccinated people to come and tell their stories. We granted regular media interviews, engaged comedians and our 484 mobile teams went to the villages to sensitise people.

“Those going for pilgrimage had no choice. They took the vaccine. Then, the COVID palliative, they felt anyone who is not vaccinated will not get it. We called religious leaders and told them about the materials in the vaccine. We wanted them to be a role model. So, they made announcements during Jumat for people to take the vaccine.”

Shuaib said the most dramatic point during the COVID-19 vaccination exercise was when some residents claimed that the vaccine improved their erection. That drove more people to the vaccination centres.

But while Jigawa is getting it right with COVID-19, the lack of adequate vaccine is impeding its fight against meningitis.

SAVING THE VULNERABLE CHILDREN

For Mahmood, one of the most challenging aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic was the handling of the Almajiris who were returned to Jigawa from other states.

He said over 5,000 almajiris were received in three months and sent to the NYSC camp isolation centre, while nine of them died due to COVID complications. The ones that were treated and discharged were offered N10,000 by the state government, returned to their LGAs and reunited with their families.

Almajiris are children, mostly from poor homes, who migrate from their homes to acquire Islamic knowledge from teachers. They are largely found in northern Nigeria where they are notorious for street begging — and with no formal education. Amid the pandemic, governors from the northern states agreed to ban the almajiri system to curb the spread of the disease.

In its multiple indicator cluster survey MICS 6 results for 2021, the United Nations Children Funds (UNICEF) said the infant and under-five mortality rate in Jigawa indicates 174 deaths per 1000 live births.

“The survey further shows that 73.9% of children in Jigawa are multi-dimensionally poor,” Rahama Farah, chief of UNICEF, Kano office, said.

“In Education, 44% of children that are supposed to be in primary school are still out of school in Jigawa.”

While the report noted that Jigawa made significant progress in child immunisation coverage, experts say there is more to be done in protecting the younger population from future disease outbreaks.

Godwin Ntadom, the chief consultant epidemiologist of the federation, said children who suffer some complications, like deafness, from infectious diseases should be enrolled in special schools to learn how to communicate.

“Children are more vulnerable during infectious disease outbreaks. They are affected by the disease and its general impact. First, all children are expected to be immunised; then, they need a prompt response of diagnosis,” Ntadom said.

“The parents should be able to recognise the disease early enough and seek medical attention in appropriate places. In case parents do not have the resources to convey their children to the hospital, the community should assist them. After recovery, they need rehabilitation.”

Nasidi, on his part, said immunisation alone cannot stop the spread of meningitis in Nigeria but it is the most important tool to use for controlling its spread in affected communities.

“Definitely, community participation in disease prevention and control strategies could enhance the effectiveness of immunisation and health promotion,” Nasidi said.

“The introduction of the conjugate meningitis vaccine and its proper deployment in the country, including immunising children, will be the best strategy to controlling the outbreak and mitigating its impact on the community.”

For Ismail Maigari, ward head of Garin-Gambo Village in Gumel LGA of the state, the community is leaving no stone unturned in ensuring that meningitis does not come back to kill the children. Residents are advised not to sleep in congested rooms, while there is an ongoing communal orientation towards building houses with big windows for effective ventilation.

Add a comment