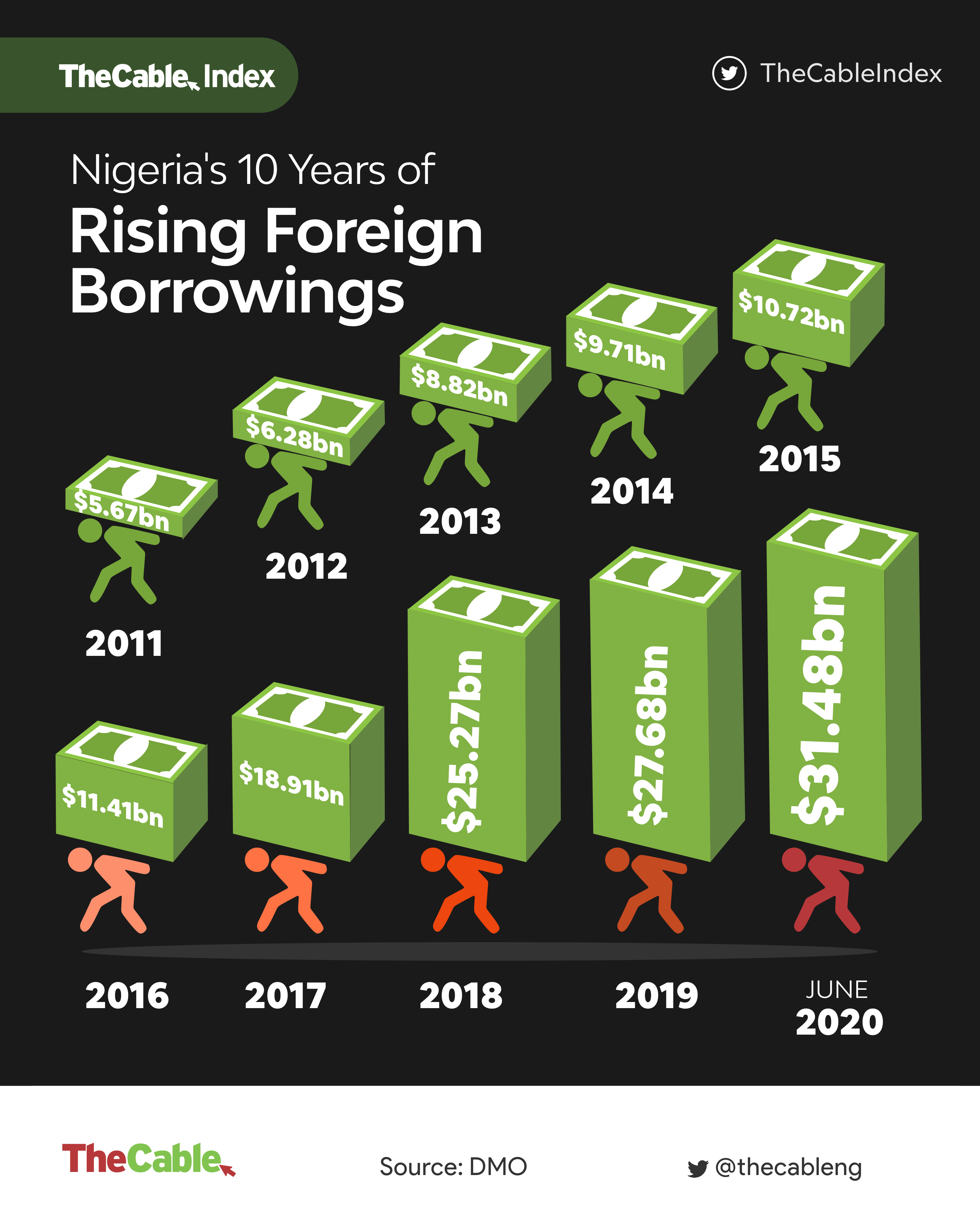

Nigeria’s foreign borrowing in the past 10 years has ballooned more than five-folds, an analysis by TheCable has shown.

Nigeria, like the rest of the world, has been grappling with the double-whammy impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and a significant revenue shortfall, raising concerns around the country’s foreign debt servicing.

Specifically, in 2011, the country’s foreign borrowing stood at $2.26 billion compared to $31.48 billion as at June 2020.

Nigeria accumulated an average of $1.5 billion in foreign debt each year between 2011 and 2016, bringing its total obligation to external creditors to $11.41 billion at the end of the period.

Advertisement

The figure rose to $18.91 billion in 2017; $25.27 billion in 2018; and $27.68 billion in 2019. External borrowings are usually obtained from foreign commercial banks, international financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank. Domestic borrowing still accounts for over 60 percent of Nigeria’s debt composition.

Nigeria’s external debt to GDP has remained low significantly at 8 percent in 2020, and by estimates, 6.3 percent in 2019 compared to some African countries such as Zambia, Egypt, and Kenya.

Advertisement

However, a debt-to-GDP may not be the best indicator of debt sustainability, especially in a country like Nigeria where tax-to-GDP hovered around an abysmal 6 percent in 2019.

Financial analysts believe a better indicator of debt sustainability is the debt service-to-revenue (DSCR) ratio. The DSCR is a measure of the cash flow available to pay current debt obligations.

Olaoluwa Boboye, an economist at CSL Stockbrokers, said the high interest in repaying the debt has put Nigeria’s low debt-to-GDP vulnerable to shocks.

“In 2016, when we had an oil price shock, the country’s external debt spiked significantly; same this year, external servicing would spike due to pressured revenue of the government,” he said.

Advertisement

Boboye explained that debt servicing during the period of shocks is always terrible, once there is currency devaluation and a slump in crude oil prices.

According to the medium-term expenditure framework and fiscal strategy (MTEF/FSP) report recently released by the federal ministry of finance, budget, and national planning, as at first quarter for the period ended March 31, Nigeria incurred a total sum of N943.12 billion in debt servicing, while the federal government-retained revenue was put at N950.56 billion.

This implies Nigeria’s debt service to revenue is estimated to be 99.2 percent during the period — the highest on record. By this, out of every N100 that Nigerian earned in Q1 2020, N99 was spent on servicing debts.

“This is an unsustainable model for Nigeria and cannot continue for too long. At some point, the government will have to increase its revenues or face further spending cuts,” Boboye said.

Advertisement

The ratio has, however, improved to 72 percent in May — still, a far cry from the IMF recommended 23 percent.

According to the Joint World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Framework for low-income countries released in 2020, a country’s debt service to revenue threshold should not exceed 23 percent.

Advertisement

According to Segun Olakoyenikan, a financial analyst, the last time the country witnessed this level of indebtedness to external creditors was as far back as 2004 when Nigeria got a debt pardon worth $18 billion and paid up a substantial amount.

Sadly, the debt has continued to accumulate, while the bigger risk is the extent of currency devaluation Nigeria has witnessed within the past 10 years, which continually makes repayments difficult.

Advertisement

“Ideally, borrowing is not a problem, but how the loans are utilised, investing borrowed funds in developmental projects capable of revamping the economy and repaying the debts in future is essential to avoid a loan default,” Olakoyenikan said.

“Although we have seen some investments, including those in road infrastructure across the country, the question is ‘are these investments making enough returns to cover up for both weaker naira and interest rates on obligations?’”

Advertisement

Add a comment