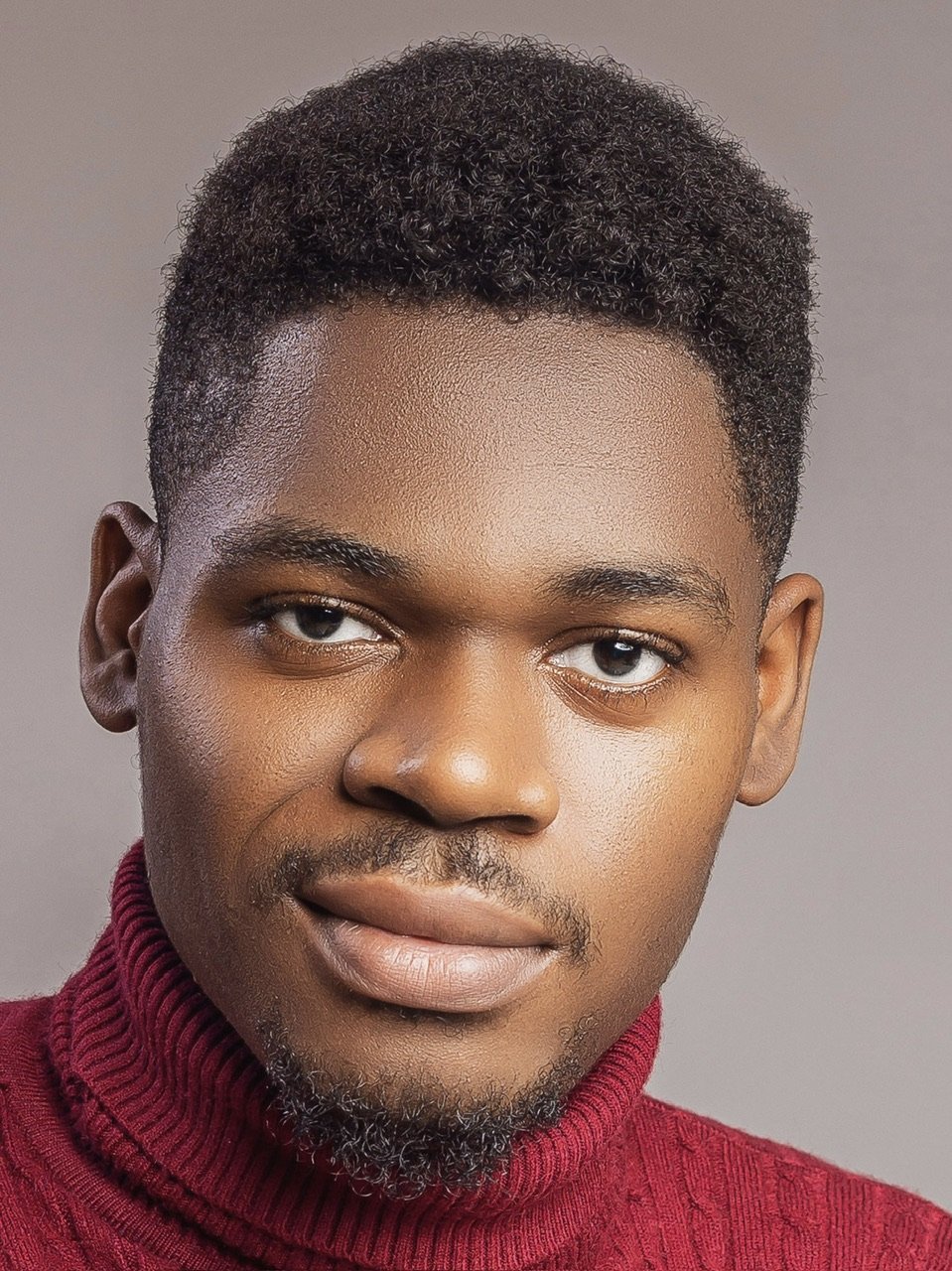

Pupils at Nomadic Primary School Gidan Ardo in Galadimawa, Giwa LGA of Kaduna | Photo: Samuel Adebanjo

Nigeria has an estimated 50 million nomads comprising pastoralists, farmers, and fisher folks who are heavily reliant on child labour. The hyperactive life of nomadism is disruptive to basic education, making nomadic children unable to fit into conventional schools. In 1989, Nigeria created a flexible system of education administered in brick classrooms, with collapsible structures, or under tree shades in out-of-town settlements where migrants ply their trade.

This scheme has continued to struggle due to insecurity, teacher attrition, and a severe shortfall in critical infrastructure. Only an average of 1.6 million children are enrolled in Nigeria’s nomadic schools at any given time, leaving the country with some 5 million out-of-school nomadic children who have little hope for future socioeconomic integration.

TheCable’s STEPHEN KENECHI visited nomadic settlements in Nigeria’s northern city of Kaduna and other small communities to document how inadequate access to education marginalises already disconnected nomads and potentially fuels crime.

Jaafar Mohammed is 10. He walks 10 kilometres from Lambel, a rural community in Kaduna state, to school every day after tilling the soil with his farmer father.

Advertisement

“School has helped me communicate better with people,” a drained Jaafar mouthed lifelessly. “I believe education will help my future, better my lifestyle, and improve my approach to cattle rearing.”

Young Jaafar is unhappy that his education has stagnated in primary five. But he is forced to choose between a dysfunctional school or no school at all.

Schools in Kaduna state, especially the nomadic ones in remote communities, face significant security threats due to banditry, kidnapping, and violent attacks. In fringe communities, banditry has forced families to abandon their homes and schools by extension. Many nomadic schools operate under minimal infrastructure, such as tree shades and isolated buildings, leaving pupils vulnerable, educators deterred from performing their duties, and parents discouraged from enrolling their wards.

Advertisement

In 2024, over 359 basic schools hit by banditry in Kaduna were marked for relocation. Uba Sani, the Kaduna state governor, said the state’s educational system faces a crisis of declining enrollment, dropping from 2.1 million in 2022 to 1.7 million in 2023.

Schools in Kajuru, Giwa, Igabi, and Chikun LGAs are affected, including nomadic ones.

Galadimawa, an administrative district in Giwa LGA located about 73km from the Zaria metropolis, hosts 25 nomadic schools, seven of which were deserted after bandits began raiding the communities in 2019.

Advertisement

Nomadic Primary School Farin Dutse is one such school.

Its building stands weathered and isolated, its walls a mixture of crumbling mud bricks and peeling plaster that hint at years of neglect. Its tin roof, streaked with rust, sits askew, allowing glimpses of the open sky through its seams. For a school that used to be teeming with children looking to learn, the structure’s windows are now hollow frames, their shutters hanging precariously or missing altogether.

Overgrown grass has reclaimed the surrounding area, creeping up as if to erase the memory of what was once a modest school. The empty doorways and silent corridors evoke a haunting quietness, a stark reminder of disrupted dreams and the lives put on hold in a community grappling with insecurity and loss.

During school hours, the winding muddy road leading to this community is packed with young children trudging along, bare feet battered and bathed with red dust, some with a raft of strung-up firewood balanced on their petite heads. Their faces, streaked with sweat and smudges of dirt, betray the exhaustion of days spent on domestic chores. The silence of the road is broken only by the rustling of dry leaves and the incoherent, distant chatter of roaming children.

Advertisement

Unable to trek to neighbouring communities to seek alternative schools, some children in this community have discontinued their education. They mostly join their parents in farming, cattle herding, and small trades like firewood sales.

As it has been for NPS Farin Dutse, so it is for six other schools, including NPS Hayin Sirdi, NPS Tudun Jatau, NPS Kudodo, NPS Gidan Bature, NPS Aginsawa, and NPS Unguwan Mashekari.

Advertisement

DEFYING THE ODDS TO ACQUIRE EDUCATION

Advertisement

The road to Galadimawa is heavily manned by uniformed police and army officials who compel droves of commuters to disembark from their automobiles and walk past a checkpoint on asphalt. But the teachers working at NPS Farin Dutse said they received stern threats from unyielding bandits to keep out of the community, with extension agents on regulatory oversight yielding to the fear of abduction.

Hassan Sulaiman, the headteacher at NPS Farin Dutse, said the local government authorities had transferred some teachers to NPS Gidan Ardo, forcing some pupils to walk 4 kilometres of unsafe bush paths from Farin Dutse to school daily, at times accompanied by their weary parents.

Advertisement

These efforts did little to nothing to stop these communities from the tight grip of bandits, pulling out of school many children who would rather not risk unsafe distances.

“The security threats started in 2018 and have persisted to this day,” Sulaiman said.

NPS Gidan Ardo is a block of two classrooms that operates on a multi-grade teaching method. There are about 50 to 70 semi-mobile nomadic children enrolled in it. Two teachers were relocated from some of the schools whose host communities were rendered inaccessible by incessant bandit activity, bringing the number of tutors there to three, excluding the headmaster.

Gidan Ardo is an unfenced structure sited two kilometres into the thick of surrounding farms and vegetation, its windows creaking from damage. Functioning for just three hours daily to imbue nomadic children with basic numeracy skills, the school has no electricity.

The school itself is not entirely safe.

As of November 2024, locals said the spouse of the immediate past village chief in Galadimawa was abducted about 2 kilometres away from Gidan Ardo and had been in captivity for two months.

Compounding these threats is that Galadimawa is a telecommunication dead zone, making it a haven for bandits who mostly raid at dusk. Cell phone reception vanishes about two kilometres in, with military intervention during such attacks taking a while to materialise.

In a small, cramped classroom, where the air is thick with the dust of northern harmattan, children in Gidan Ardo sit shoulder to shoulder, their bare feet poking out from under their worn clothes. Their skin, dry and pale from the harsh winds, bears the marks of a life far removed from comfort.

With slippers, no uniforms, barely enough writing materials, and only chalkboards to support their lessons, they chew on pencils. Their faces beam with innocent exuberance as they chatter in a mix of Hausa and Fulfulde, unbothered that the classroom offered no protection from the danger lurking outside, the very threats they have learned to ignore.

A SCHOOL FOR HUNDREDS HAS NO TEACHER

At the heart of Kachia in southern Kaduna, what is considered a model for standard nomadic schools has remained stifled in a state of dysfunction for over one year. A debilitating shortage of tutors subjects the school’s pupils to the daily routine of roaming the premises and returning home after three hours without taking classes.

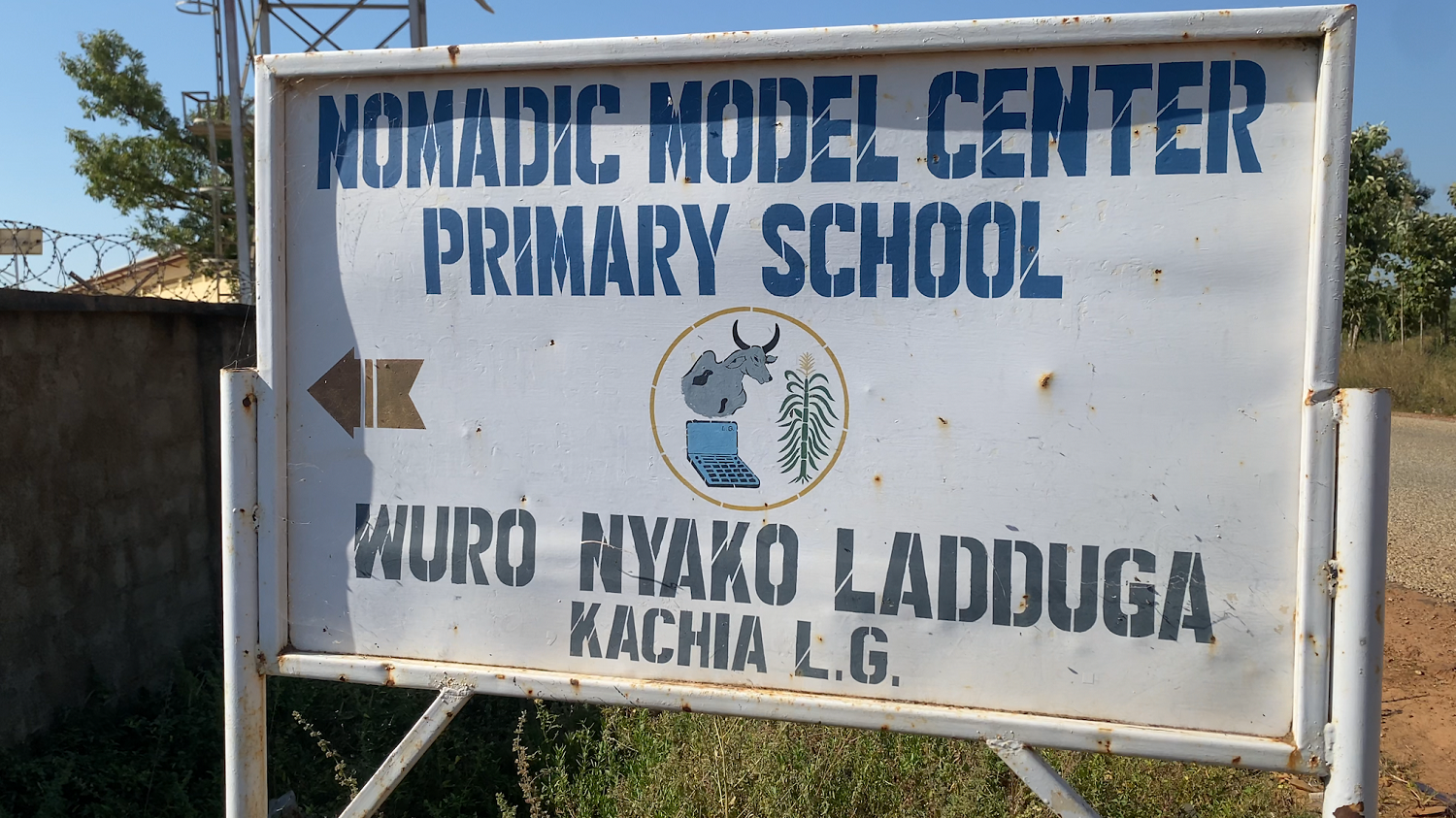

NPS Wuro Nyako sits on two hectares of land at the very centre of Kaduna’s famous Ladduga Grazing Reserve, an expansive swathe of virgin land spanning 33,114 hectares intended as a refuge for migrant nomads seeking safety away from the underbelly of deadly communal conflicts.

NPS Wuro Nyako operates between 9 am and 12 pm. Its pre-teen students only report to school after doing a morning round of domestic work with their herd or on the farm.

Thriving heavily on non-profit donations, the school self-generates its electricity with 24 solar panels of 250 watts each and a backup generator of 100kva. It hosts a shea butter processing plant. The nomads and their children have access to a functional grinder, thresher, sheller, dehusker, decorticator, oil expellers, and planters.

NPS Wuro Nyako has a tailoring factory equipped with 33+ electric-powered sewing, whipping, and knitting machines with a digital board for instructional purposes. There is a honey processing unit, a veterinary clinic with brick-built drinkers, and a massive water tank for cattle herding. Its ICT centre is equipped with projectors, scanners, UPS machines, and at least 24 desktop computers mounted on wooden cubicles. The school has a library packed with books on nomadic life.

These resources could engage nomadic youth and generate major commercial activity, but they gather dust due to the lack of teachers to run them and train the nomadic students.

NPS Wuro Nyako could be aptly described as an institution that has everything, yet lacks everything; holding so much potential, yet, crippled by the weight of its deficiencies.

The night before TheCable visited Ladugga on November 14, 16 mercenaries hired from neighbouring states by locals to ward off bandit activity were massacred in a bloody ambush that never made the news. There was palpable trepidation in the air, with armed security mounting roadblocks and checkpoints.

NPS Wuro Nyako bore the likeness of an outpost in the heart of danger and neglect.

Pupils were playing football in the open on bare feet whitened with the dust of extremely dry harmattan. The school was supposed to be in session, but it wasn’t. The school had not one teacher, save for a volunteer NCE graduate, Usman Muhammed, who was initially away for a community meeting.

Over one year of unproductive schooling had nomadic parents in Ladduga pulling out their wards, a reality that has left the school’s enrollment numbers fluctuating at intervals.

A primary school needs at least six multi-subject teachers to manage each class. Data obtained by TheCable showed Nigeria had 19,728 “qualified” nomadic teachers and 7,413 nomadic primary schools. This amounts to a national total of 44,478 in required teachers and a deficit of 24,750.

SUSTAINED BY COMMUNITY EFFORT

Wuro Nyako has benefited from World Bank-affiliated basic education interventions, a signpost showed.

Salisu Yunusa, a man in his 60s who would later become a community leader and an unpaid informal administrator at the school, told TheCable he donated the land NPS Wuro Nyako sits. But donations, Yunusa noted, are no sustainable funding source in the long term.

“NPS Wuronyako was founded in 1997,” Salisu said in Fulfulde, showing this reporter around the school. “Initially, the community sponsored it. We provided resources to facilitate teaching at the school out of pocket. We were the ones hiring and paying volunteer teachers. Then, the government intervened.”

Between 2017 and 2018, the Nasir el-Rufai government in Kaduna fired over 22,000 teachers deemed unqualified after 83 per cent of the tutors in public schools were said to have scored below 25 per cent in an arithmetic and literacy test. Sources affiliated with NPS Wuro Nyako said the teachers who were later sent as replacements were young and less resilient NCE graduates, often unwilling to work in suboptimal conditions that have become the norm for nomads or reluctant to teach in unsafe remote communities.

“Insecurity in the area and the disengagement of teachers made things hard,” said headteacher Halimat Buhari, who was away for a nomadic school cluster meeting when TheCable visited.

“There is a stigma that nomads are terrorists. People stay away from anything that has to do with them. We tried persuasion, but it didn’t help. Most of Ladduga’s 39 nomadic schools have no teachers.”

Halimat lives 30 kilometres away from NPS Wuro Nyako, commuting on commercial bikes past Crossing, a community where young bandits raid homes, kill, and abduct entire families for ransom at intervals.

“I can’t go every day. Coming from Crossing to Wuro Nyako every day is dangerous,” she explained. “I’m considering moving into the school and returning only on weekends, but the quarters need furnishing.”

Halimat said a model school the size of NPS Wuro Nyako, which has a total of 594 students as of this reporting, needs 50 niche tutors to work optimally or 12 class-based teachers grounded in all subjects of the nomadic curriculum to be “manageable” at the targeted student-teacher ratio of 50:1.

Usman Mohammed started schooling at NPS Wuro Nyako in 2001, finished in 2007, moved to Kogi state for secondary education, obtained an NCE, and returned to Wuro Nyako to volunteer as a teacher as part of the community-wide effort to keep the struggling nomadic school functioning.

“The system was productive in my time,” he recounted. “Hardly was there a primary 5 student who couldn’t speak English and Hausa. I returned, only to find there were no more teachers.”

Far away from Kachia, in Soba, Makarfi, Ikara, Kudan, and Kubau, semi-nomadic Fulani herders establish schools and hire teachers, most skilled only enough to impart Arabic education.

OVER 5.5 MILLION NOMADIC CHILDREN ARE OUT OF SCHOOL

In Nigeria, nomads are everywhere. They are perched on the fringes of villages and towns, herding their cattle, farming, and fishing in the thick of remote vegetation. But nomadic communities remain marginalised despite their omnipresence, their existence treated as an afterthought.

Their transient way of life renders them invisible to the machinery of social interventions and policy. This invisibility is observable in the education sector, where nomadic children grapple with dysfunctional schools and a lack of teachers.

Their activities sustain local economies, but their lack of substantial social acknowledgment locks them out of systemic support. This exclusion perpetuates cycles of poverty, denying nomadic children the basic right to sustainable education and hindering their future socioeconomic reintegration.

Established in 1989 by a military decree, the National Commission for Nomadic Education is tasked with catering to the educational needs of Nigeria’s socially excluded or educationally disadvantaged migrants.

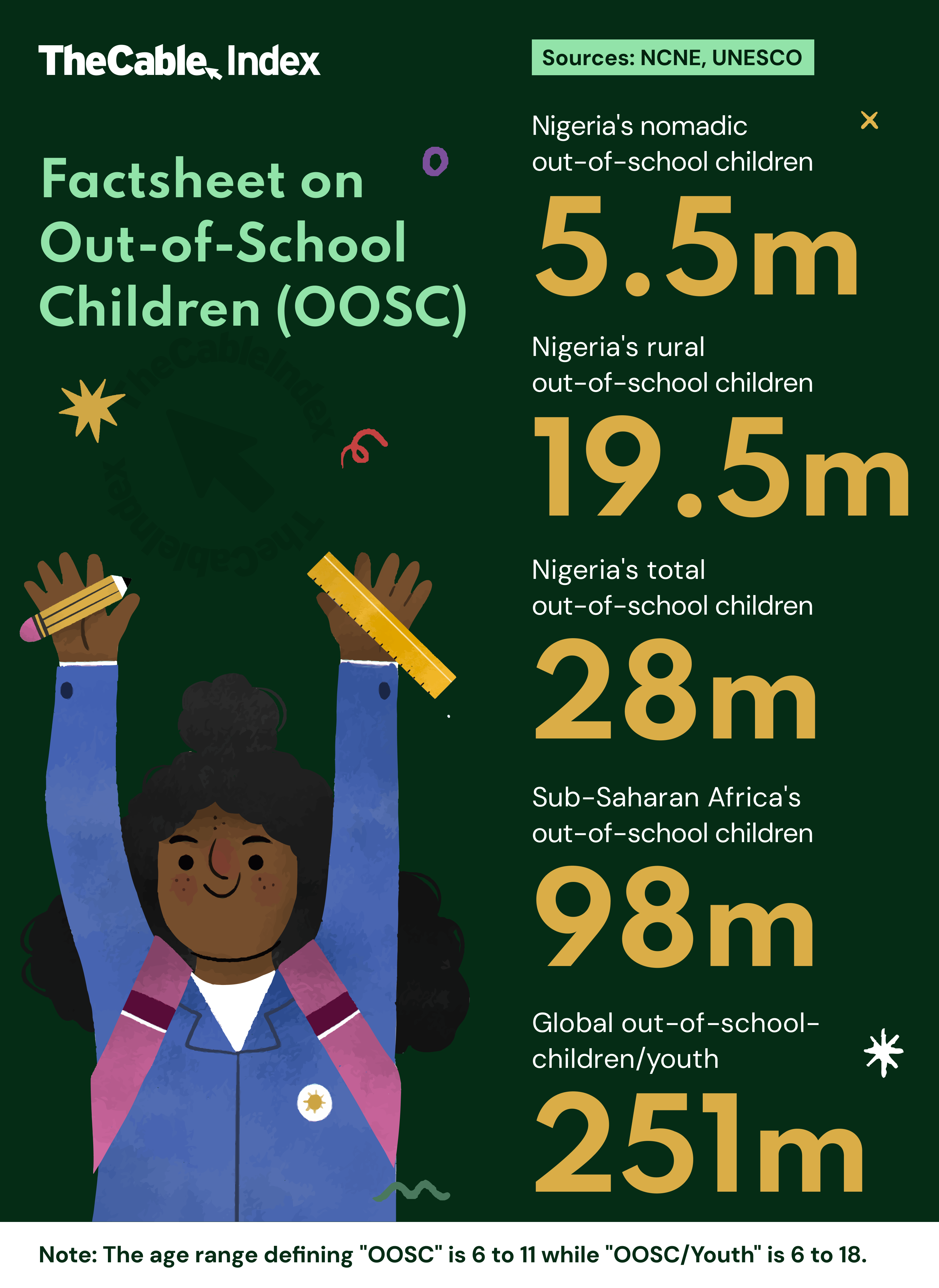

NCNE estimates Nigeria’s nomadic population to be at about 50 million. Only 10 to 12 per cent of this figure is literate. The UNESCO Institute of Statistics data shows that Nigeria has a major out-of-school crisis. About 28 million children between ages 6 and 11 are not in school, with over 19.5 million in rural communities. Further data from the NCNE shows that 5.5 million school-age nomadic children are out of school, with education policy discourse in Nigeria rarely highlighting this.

UNESCO recommends a student-teacher ratio of 40:1 for primary and 25:1 for secondary schools in developing countries to avoid “learning poverty” and ease pressure on infrastructure, with a cap of 10 per cent for rates exceeding this threshold.

Many nomadic schools in Nigeria exceed this, as seen with NPS Wuro Nyako, which has a student-teacher ratio of 600:1. More holistically, NCNE data show that enrollment in nomadic schools sits at about 1.8 million, with just around 19,728 qualified teachers employed as of 2023. This yields about 91:1 in student-teacher ratio, a rate above the UNESCO threshold by 125 per cent. An additional 6,932, mostly school dropouts, had to be engaged to tutor in nomadic schools with no teachers at all.

The NCNE database shows that Nigeria had a total of 7,413 nomadic schools spread across the country as of 2023. How many of them are fully functional remains unclear. The commission said it needs at least 30,000 to mop up Nigeria’s out-of-school nomadic children.

AS NOMADS MIGRATE SOUTH, THEIR CHILDREN NEED SCHOOL

About 30 million of Nigeria’s 50 million nomads are pastoralists, most of whom are in the north. They herd animals and are mainly from the Fulani ethnic group, often called “Fulbe”. They include settled, semi-nomadic, and nomadic (wodaabe) communities.

Migration in livestock farming is mostly to search for pasture, water, disease-free communities, and a secure environment. Up north, desertification, increasing aridity, insecurity, cattle rustling, population density, and the conversion of grazing routes/reserves for farming force Fulbe people to migrate south.

“Rainfall pattern is shifting from eight to six, to four months yearly. Some areas have just three months of rainfall. There is no green grass anymore. All the states in the north are affected,” said Umar Ardo, director of extension education at NCNE.

Over a long period, the herders and their cattle migrate on foot from states like Kebbi, Sokoto, Zamfara, Katsina, Kano, Jigawa, Yobe, Borno, Bauchi, Gombe, Adamawa, and Taraba.

They move to the middle belt states like Plateau, Kaduna, Niger, and Kwara, to converge in Lokoja. From there, many migrate further down south to Edo. Some cross and move south-east to Enugu. Others cross from Benue to Calabar in the south-south.

The movement is from the north to the middle belt and down south, where there is rainfall and vegetation.

The Wodaabe are more mobile, crossing state and national borders to Ghana, Togo, and the Benin Republic.

“Some pastoralists move because they are not secure,” Umar added. “They are killed. They are also categorised as bandits. Many lost their livelihood. Animals are taken. Some are kidnapped and raped.”

Umar said the north-south movement will continue towards the foreseeable future, regardless of local laws or policies, resulting in an increasing population of migrant children who will need basic education.

“When they move, we link them with our zonal offices, state directors, and local governments. The teachers are posted and the schools re-established,” Umar noted.

Most nomadic schools are location-based, and it may not always be practical to cater to active migrants via mobile schools. In Nigeria, only local governments and state basic education boards hire public school teachers, most of whom are only trained to teach in conventional schools. Due to stretched resources, staffing troubles, and language barriers, many migrant nomad children remain unschooled.

Add a comment