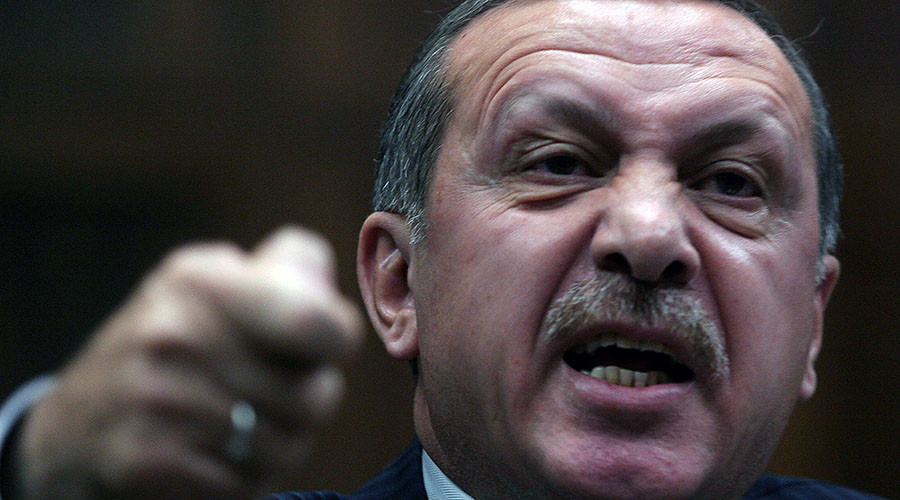

Three Wednesdays ago I wrote a cautiously optimistic piece on these pages titled “An end to Erdogan’s hubris?” It was about what I thought could be the beginning of the end of what I described as Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s, hubris.

As arguably the most successful politician in modern Turkey, the man has pulled all stops to make himself the country’s first executive president since he stepped aside in 2014 as prime minister after serving for three successive terms from 2003. During that period he transformed Turkey into one of the world’s leading economies and stable democracies.

That imperial ambition, apparently born out of his untenable, albeit understandable, presumption that only he knows best what’s good for his country, has been the source of his country’s recent economic and political travails.

It was this hubris that led him to his unsuccessful openly partisan campaign for his ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), which he co-founded in 2002, to win the two-thirds majority it needed to change the country’s parliamentary system into into a presidential one during the June 2015 elections. It was the same hubris that, along the way, led him into cracking down hard on all opposition to his ambition, real and imagined.

Advertisement

It was also what led him to reverse the constructive engagement he had entered with the Kurdish minorities in the country’s south-east in his years as prime minister to bring an end to their violent rebellion. The list goes on and on. But it culminated in sacking his faithful prime minister, Professor Ahmet Davutoglu, last June, essentially because the man had reportedly not shown enough enthusiasm in his support for his boss’s imperial ambition.

Then terrorists struck the Atatürk International Airport in Istanbul, the country’s business capital, on June 28. It was not the first such attack and, as casualties go, it was also not the highest. However, the attack on the airport as a great symbol of the country’s transformation into a stable, thriving and modern political-economy, attracted the widest global media coverage.

In the wake of the attack, Erdogan announced that he was restoring his country’s ties with Israel, severed decades ago. He also apologized to Russia over his downing this year of one of their fighter jets that he claimed has crossed into his country on a bombing raid against the Islamic State in Syria.

Advertisement

My article of three weeks ago was to express the hope that, for Turkey’s case if nothing else, Erdogan would extend the same softening of his belligerence towards his perceived enemies outside to those inside. After the July 15, happily unsuccessful, military coup attempt against him, it is now apparent that my hope was forlorn.

Since that coup he has cracked down even harder on his enemies within, real and imagined. So far he has sacked or suspended more than 60,000 workers, soldiers, police, judges, university lecturers and journalists right across the public sector on mere suspicion of their involvement in the coup. He has sworn to crack down even harder.

Top of the list of his self-declared enemies has been his erstwhile ally in his long-drawn fight against the country’s Kemalist military and civilian secularists, the self-exiled cleric, Fethullah Gulen, whose Hismet (Service in Turkish) Movement, the president had long ago condemned as “criminal.” Indeed the president has been quick, too quick some would say, to accuse his former ally as the number one culprit and intensify his demand for Gulen’s extradition from his self-exile home in Philadelphia, United States.

As allies, Erdogan and Gulen worked hand-in-glove to purge the military of Kemalists and restore “mildly Islamist” values and symbols, like the ban on alcohol and the wearing of hijab, into public life. The alliance started falling apart from 2013 partly over Erdogan’s ambition to transform himself into an executive president and partly over a 100-billion-dollar corruption scandal which broke out in December of that year in which several of Erdogan’s ministers and relations were implicated and which eventually led to the resignation of some of the ministers.

Advertisement

Since the falling apart of the two, Erdogan has spared no opportunity to purge all sectors in his country, including the judiciary, the police, the military and the media, of those he perceives as Gulen disciples and supporters. Abroad he has also spared no opportunity to persuade other countries to shut down businesses and institutions belonging to or affiliated to the Hismet Movement, several off them well entrenched in Africa, including here in Nigeria.

I was spending the weekend of the coup in Turkey at home in Bida, blissfully unaware of goings-on in the Internet world when Sarkin Karshi, Alhaji Ismaila Mohammed, called me on the phone and said I must be happy at the unfolding events in Turkey, considering my seeming antipathy towards Erdogan. Not knowing what he was talking about, I asked him what was going on. He said he was surprised I didn’t know a military coup was taking place in Turkey, as if in response to my July 6 article.

I told him a coup may be bad for Erdogan but it certainly couldn’t be good for Turkey, certainly not after none of the six coups the country had suffered between 1960 and 2007 ever brought any good to the country.

As things turned out the coup failed, ironically thanks in the main to the very media, in this case the social media, which Erdogan has done his best to crack down hard upon; as we have since been told, it was his use of an iPhone to urge his fellow countrymen to rise against the coup which turned the tide in his favour.

Advertisement

That people heeded his call is obviously a reflection of his support in the country, in spite of his authoritarian tendency. But without the media he would never have had the weapon to rally his countrymen against the coup.

There are people inside and outside the country who believe the president stage-managed the coup to have a pretext for finally getting rid of all those opposed to his imperial ambitions. One such person is Cemil Yigit, a spokesman of Ufuk Dialogue, an affiliate of the Hismet Movement in Nigeria which promotes interfaith dialogue and among whose patrons are the Sultan of Sokoto, Alhaji Sa’ad Abubakar, and the Catholic Archbishop of Abuja, John Cardinal Onaiyekan.

Advertisement

In an interview in Daily Trust (July 24) he said, “Many analysts believe that this coup attempt was stage-managed by the Erdogan administration to consolidate power. When you look at events of the past days there is a lot of evidence that it might be true.”

One of the events Yigit mentioned was the fact that even as the coup was still unfolding the president was already certain that Gulen was the main culprit. Another was the fact that Gulen was among the first to condemn it even when it was uncertain where the chips would fall.

Advertisement

There are, on the other hand, others who believe Gulen may indeed be the main culprit. One such person is Dani Rodrik, a Turkish economist and Ford Foundation Professor of International Political Economy at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University.

“All of this,” he said in an article on his blog on July 23, “points to the Gulen movement as the immediate culprit behind the coup attempt. Gulenists had both the capability and the motive to launch the coup,” his “all of this” referring to what he said went “much beyond the schools, charities, and inter-faith activities with which it presents itself to the world.”

Advertisement

The movement, he said, “also has a dark underbelly engaged in covert activities such as evidence fabrication, wiretapping, disinformation, blackmail, and judicial manipulation.”

Who ever is right between Yigit and Rodrik, the greater concern should be Erdogan’s response to the coup. For me his greatest enemy remains his imperial ambition, not the Gulenists, or the Kurds or all those opposed to his ambition.

The right lesson for him to learn from the coup attempt therefore is to abandon his ambition and return to the accommodation he had with the Gulenists and the one he sought with the Kurds in his days as prime minister.

Perhaps not being knowledgeable about the mysterious ways of Turkish politics I fail to see, like Rodrik, what motive Gulen, who seeks to promote peace between the world’s religions and whose creed is religion in the service of humanity, regardless of anyone’s faith, would have in worldly political power and material wealth.

Of course, we’ve seen a similar thing happen before in Iran when the late Ayatollah Khomeini living in exile abroad, returned home to ultimate political power in his country after the Shah was overthrown. But then Turkey is a country of Sunni Islam and therefore has no clerical hierarchy similar to Iran’s that can provide Gulen with a platform to claim any crown.

Alas!, all indications so far is that the prospects that Turkey may see an end to their president’s hubris is bleak – very bleak.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment