1 of 34

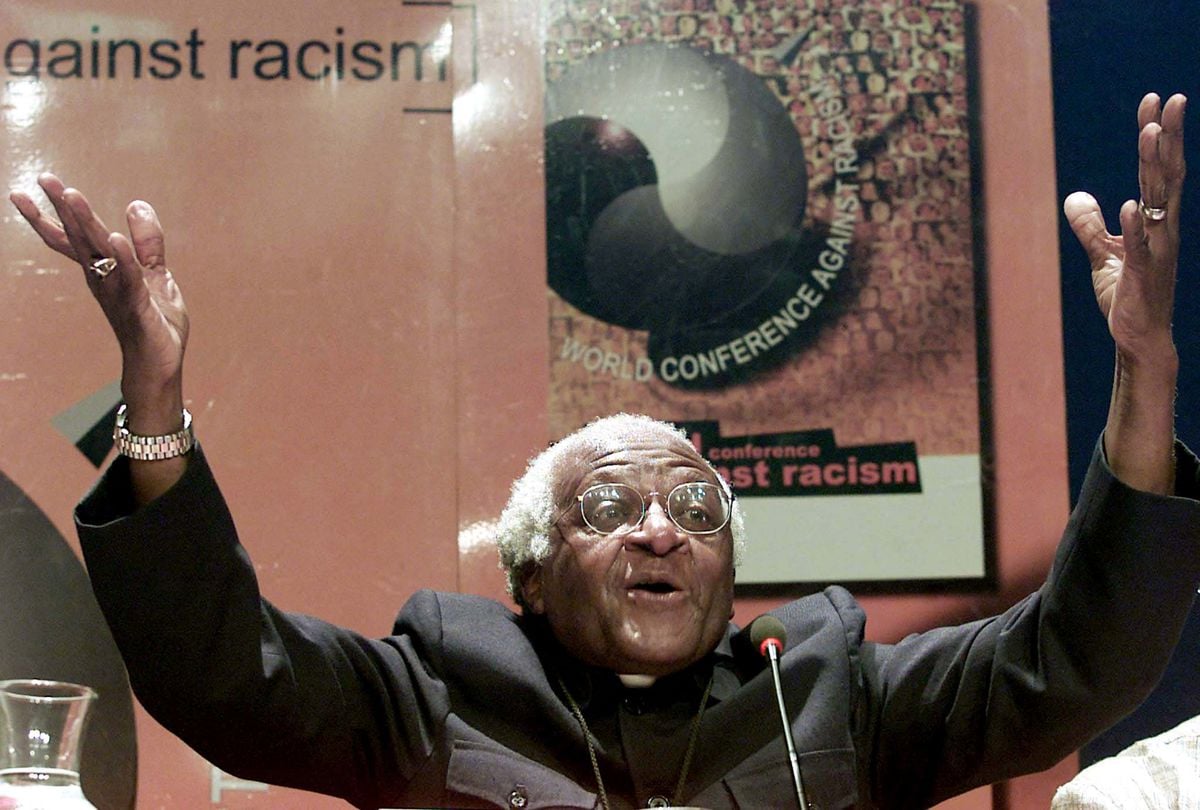

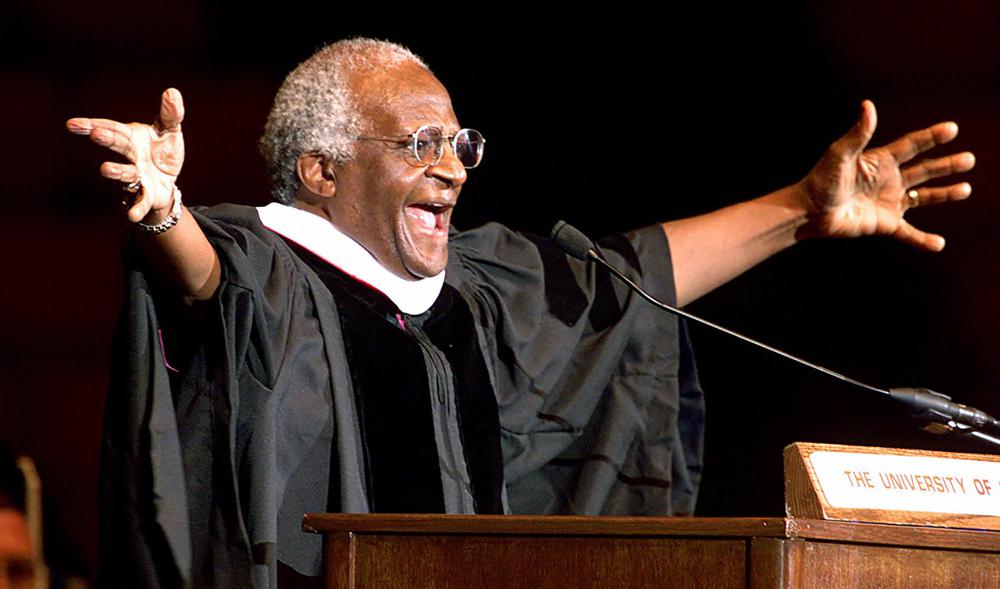

FILE - Anglican Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu, speaks during an interview with the Associated Press in Pretoria, South Africa, Friday, March 21, 2003. Tutu, South Africa’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning activist for racial justice and LGBT rights and retired Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town, has died at the age of 90, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa has announced. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

A life well spent. A journey thoroughly maximised. A cycle that birthed generational impact. If the most thoughtful definition of a life well spent is that which proffered hope to the beleaguered, gave voice to the muffled and shone spotlight to the plight of the downtrodden, then Desmond Tutu can be styled as one of the few humans blessed with a richly expended life.

When the news of his demise at the age of 90 broke just a few hours after the 2021 Christmas, the world mourned the passage of a man who showed humanity that revolution must not always come from the cold nuzzles of guns and the violence they crank up. A man who sued for peace and not docility, called for emancipation and not destruction, demanded moderation but was not a fencist. Tutu was, indeed, a man of God. One of the vital cogs in the liberation of black South Africans from the servitude of apartheid.

TEACHER’S SON WHO ASPIRED TO BE A MEDICAL DOCTOR

In 1931, Tutu was born in Klerksdorp, a town around 170km to the west of Johannesburg. His father was a teacher at a local mission school. Tutu, who grew up in a mud-brick house, once described his childhood as thus: “Although we weren’t affluent, we were not destitute either.” A young Tutu wanted to pursue a career in medicine, but he could not afford the cost of getting trained — instead became a schoolteacher.

In 1953, after the white minority National Party government introduced the ‘Bantu Education Act’ to further their apartheid system of racial segregation and white domination, Tutu left the teaching profession, and he began studying to become an Anglican priest.

Advertisement

NON-VIOLENT TEACHINGS AND STRUGGLES DURING APARTHEID

Tutu used the pulpit to promulgate peaceful agitation against the discrimination of the apartheid movement. He would wad through crowds of seething black protesters and offer calming words and prayers as they get surrounded by belligerent police officers. He publicly condemned the discriminatory system to his majorly white congregation and boldly supported an international economic boycott of South Africa over apartheid.

Despite his non-violent stand, Tutu was not undisturbed by the iron-clad government hand that sought to vigorously quiet all voices of dissent against apartheid. Once after his public endorsement of economic sanctions, he was cross-examined by two ministers and was eventually remanded, with his passport seized.

Advertisement

Tutu was also arrested and his travelling documents confiscated for participating in peaceful rallies. When the other leaders of the anti-apartheid movement were getting weary of the non-violent tactic, Tutu preached patience, saying, “Moses went to Pharaoh repeatedly to secure the release of the Israelites”.

NOBEL PEACE PRIZE

After being nominated three previous times, in 1984, Tutu was awarded the Nobel peace prize.

In his Nobel lecture, Tutu didn’t mince words as he preached the unjustness of racial inequality and how it dehumanises both the oppressed and the oppressor.

“When will we learn that human beings are of infinite value because they have been created in the image of God and that it is a blasphemy to treat them as if they were less than this and to do so ultimately recoils on those who do this? In dehumanizing others, they are themselves dehumanized. Perhaps oppression dehumanizes the oppressor as much as, if not more than, the oppressed. They need each other to become truly free, to become human. We can be human only in fellowship, in community, in koinonia, in peace,” he said.

Advertisement

“Let us work to be peacemakers, those given a wonderful share in Our Lord’s ministry of reconciliation. If we want peace, so we have been told, let us work for justice. Let us beat our swords into ploughshares.”

POST-APARTHEID AND ‘RAINBOW NATION’

Tutu had always described South Africa as ‘The Rainbow Nation’ because of its multiracial population. Following the end of apartheid and the emergence of Nelson Mandela as South Africa’s first black president in 1994, the name stuck.

He was appointed head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which investigated allegations of human rights abuses during the apartheid era.

Advertisement

He proposed that the TRC adopt a threefold approach which he stated as “the first being confession, with those responsible for human rights abuses fully disclosing their activities, the second being forgiveness in the form of a legal amnesty from prosecution, and the third being restitution, with the perpetrators making amends to their victims”.

PRO-GAY VIEWS AND ISSUED WITH THE CHURCH

Tutu retired from the church in 1996 to face the TRC and its commitment squarely. But he was still a significant member of the Anglican Church in the country and around the world. However, he began having issues with the church over his pro-gay views, which the Anglican teaching sees as “unchristian”.

Advertisement

After bishops had emphasised the church’s anti-LGBT stand at the 1998 Lambeth Conference, Tutu wrote to George Carey, former Archbishop of Canterbury, saying that “I am ashamed to be an Anglican”.

Then he famously declared in 2013 that “I would refuse to go to a homophobic heaven. No, I would say sorry, I mean I would much rather go to the other place. I would not worship a God who is homophobic, and that is how deeply I feel about this. I am as passionate about this campaign as I ever was about apartheid. For me, it is at the same level”.

Advertisement

Tutu will be unforgettable for, among many other things, the passionate conviction and sincerity of purpose with which he championed many causes while he lived.

Advertisement

Add a comment