Mbel Segun

Mabel Segun had numerous gifts. One was the gift of a lovely and erudite family. Another was the gift of agility and coordinated body movement necessary for sports. But the most important was the gift of memory — the ability to recall specific events, regardless of the date, as though they had unfolded mere minutes prior. An innate talent that has always been the arable soil for a literary ambition. The gift was the sacred roots where Mabel’s literary success sprouted forth.

She was a renowned writer with shelves of books and awards, and was dubbed “matriarch of children’s literature” by late Bola Ige, a judiciary scholar and former minister of justice.

She was the first Nigerian woman to play competitive table tennis. Mabel was also a prolific badminton player and she won championships. She was also a celebrated broadcaster.

The history of Nigerian literature will be left with a giant, gaping hole if she’s omitted. She was a classmate of Chinua Achebe, the legendary author of ‘Things Fall Apart’, and together they edited the University Herald, a student magazine, at the University College, Ibadan.

Advertisement

Mabel was a pioneer of female authorship in Nigeria and Africa — a woman whose work and drive stood out of the male-dominated post-colonial African literary scene. Mabel described herself as the second Nigerian female author published abroad. She and her fellow contemporary female authors hoisted the beacon that became the lighthouse for the future generations of African women writers.

Her passing on Thursday was almost symbolic: she died two days after her 95th birthday and during the Women’s History Month.

A CLERGYMAN’S DAUGHTER

Advertisement

She was born Mabel Dorothy Aig-Imoukhuede on March 5, 1930, in Ondo town in the part of Nigeria that would later be named Ondo state.

Her father was Isaiah Aigbovbioise Imoukhuede, a clergyman who hailed from Sabongida Ora in Edo state, and was proselytising gospel in Ondo when Eunice, his wife, gave birth to Mabel.

Mabel’s father was also a writer of enormous repute who translated Yoruba hymn books to his local Ora language. He also wrote the first Ora primer, a short history of Ora people.

Growing up in a scholarly home influenced Mabel’s perspective on knowledge, morality, and literary muse.

Advertisement

She described her father as her “role model” and remembered every detail of the time spent with him, writing, learning, preaching and loving people.

Mabel had her primary education in Akure and Ile-Ife, where one of her brothers, Frank Aig-Imoukhuede, the father of Aigboje, the former chairman of Access Bank plc, was born. She proceeded to CMS Girls School, Lagos, Nigeria’s oldest girls’ secondary school.

Mabel’s warm literary glow, nursed under her father’s influence, developed into full-blown penwomanship during her secondary school days.

A teacher named Ore Cole coached her through the beauty of poetry. The teacher read ‘Sea Fever’, a poem by John Masefield, to Mabel’s class and opened another dimension of language possibilities to the youngster.

Advertisement

“It was easy for us to write because the teachers we had were people who influenced us. They had a deep feeling about writing. For example, I became interested in poetry because there was a teacher who made poetry come alive in the way she taught it,” Mabel said in a chat with The Nation in 2020.

“She read a poem to us, “Sea Fever”, that talks about the sea and how it felt to be on a boat on the sea. It influenced me a lot that so much so I wanted to become a sailor. We could see the sea and the ships on it. That is how a good teacher can influence you.

Advertisement

“I never forgot her all my life. That is why I have always advocated that the role of the teachers in education cannot be overemphasised. They are influencers.”

Advertisement

ACHEBE’S CLASSMATE

Mabel enrolled at the University College, Ibadan, after her secondary education. She studied English, Latin and History.

Advertisement

Her contemporaries in the school include Grace Alele-Williams, first Nigerian female professor of mathematics; Christopher Okigbo, a renowned poet; Chukwuemeka Ike, the celebrated author of The Potter’s Wheel, Bola Ige, a former minister of justice, among others.

But she was close to Chinua Achebe, her classmate in English and History classes.

“He [Achebe] loved dancing and we used to go to the dancing club together,” Mabel recounted in a chat with PM News in 2013.

“We were taught different steps – not the lazy dancing you young people do nowadays that you don’t learn anything and you just throw your arms and legs up! Ours was a properly structured kind of dancing, where you had to pay attention and learn where to put your feet. So, Achebe and I became close through that.”

Together, they began working on the editorial team of University Herald, a student magazine. Achebe was the editor and Mabel was the assistant editor.

During their close interactions, Mabel noticed the precocious wisdom and language gift that would eventually propel Achebe to global literary stardom.

“One thing I noticed about him later in life – because you learn about people as you go along – was that he was older than his years,” Mabel said.

“I learnt that when he was young, he associated a lot with elders in his hometown, Ogidi. So he acquired this sort of elderly behaviour. He was very sensible and behaved more like an elderly person who could comport himself in the society.

“He had a very good sense of humour that I admired very much. It was not the kind of stupid humour that you see nowadays being displayed by the so-called comedians! Achebe had a sort of subtle humour which showed his deep knowledge of the English language. I enjoyed it so much.”

She was also a founding member of the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) alongside Achebe in 1980.

‘THE SECOND NIGERIAN FEMALE PUBLISHED ABROAD’

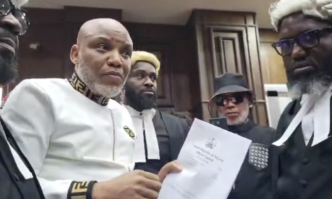

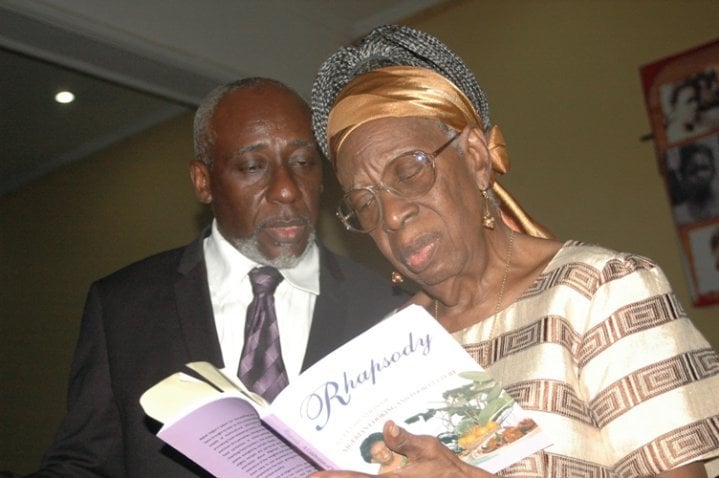

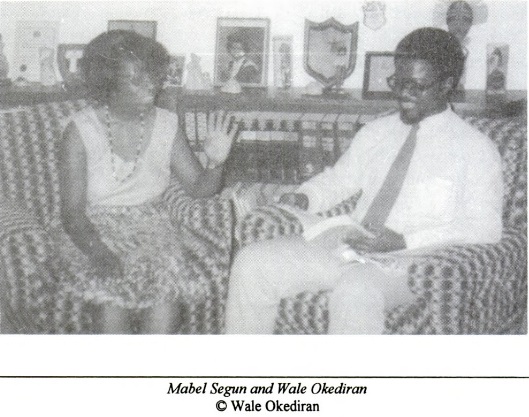

In a chat with Wale Okediran in The Gift of Memory in 1997, Mabel said he was the “second Nigerian female to be published abroad”.

She recounted that three of her poems were translated into German and published by Schwarzer Orpheus, a German anthology, in 1954.

Mabel’s poems were published 12 years before Flora Nwapa published ‘Efuru’, her debut novel under Heinemann in the UK.

Nwapa is widely considered the first African female to be published abroad. But Mabel had a contrary view.

“Flora Nwapa is not the first published Nigerian female writer. In ‘Nigerian Women in the Arts’, Phebean Itayemi, now Phebean Ogundipe, has this distinction. Her short story, which won a British Council competition in 1946, was published in an anthology,” Mabel said.

“She co-authored a folktale collection in the fifties and that ended her creative writing career.”

‘MY FIRST HUSBAND BURNT MY MANUSCRIPTS’

Before she eventually became successful, Mabel, like some of her female literary peers, had challenges with their spouses who didn’t want them to pursue their ambitions.

Mabel narrated how her first husband destroyed her unpublished manuscripts because of jealousy.

“My first husband burnt my first yet-to-be-published novel because he did not want me to become famous,” she said in a chat with PM News in 1998.

“Luckily for me, it was a white judge while we were in England who presided over the case. He dissolved the marriage.”

She said she had “terrible experience” with her second husband too.

“My in-laws were jealous of my success. They said my name was always being aired on TV. Some claim I was too great for them.”

The second marriage lasted for 15 years.

AFRICAN CHILDREN’S BOOK PIONEER

Mabel is revered as a champion of children’s books in Nigeria. Following her flirtation with the styles and beauty of poetry, she eventually discovered her talent for crafting complex ideas into simple language for kids to understand easily.

Mabel’s debut work was the critically acclaimed ‘My Father’s Daughter’ published in 1965. The autobiographical work was built on Mabel’s gift of memory and was an account of her childhood bond with her father in south-west Nigeria. The book was a hit with African children who saw their experiences on the pages for the first time. The work was also considered a response to westernised narratives like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, among others, that preceded it.

‘My Father’s Daughter’ was translated into several foreign languages, and many readers were struck by Mabel’s vivid remembrance of her childhood.

“Quite a few people have taken me up on this. You see, some people are gifted with remembering what happened to them at an early age. I am one of them,” she said.

“I particularly remember that part of my childhood because they impressed themselves on my mind. My father, a talented and versatile clergyman, had a strong, impressive personality and we were very close.

“When I saw our nursemaid after forty years and recognised her, she was surprised. I was, too, because I am not good at remembering faces. I had a very happy early childhood and its memories can never be erased.”

Mabel published ‘Under the Mango Tree’ in 1979 alongside Neville Grant. The book is an anthology of songs and poems for primary school students.

Others followed: Youth Day Parade in 1984, Olu and the Broken Statue in 1985, My Mother’s Daughter in 1986, The First Corn in 1989, The Twins and the Tree Spirits in 1991.

In 1978, she founded the Children’s Literature Association of Nigeria and twelve years later, she set up the Children’s Documentation and Research Centre in Ibadan.

“Some think children’s literature is easy to write. They don’t know it’s more difficult than adult literature. This is because you have to go into their minds,” she said.

“To write for children, you have to write for different ages and that’s why it’s difficult. You have to study their psychology. Some write as if children are measured with one flat stick.

“For example, I can’t write for teenagers because I don’t know them or what they think about. You have to study the different ages of children.

“You have to know the children, what they consider important and what’s on their minds. You also have to find out their attention span.”

FIRST NIGERIAN FEMALE COMPETITIVE TABLE TENNIS PLAYER

Mabel described herself as “honorary gentleman”; not a tomboy. According to her, as a child, “I was doing everything that the boys did.”

“I was swimming, canoeing, playing table tennis, shooting birds at Obalende, which was a bush then,” she said.

Table tennis was the sport at which she succeeded the most. In 1954, she became the first Nigerian female table tennis player. Numerous laurels followed both nationally and on the continent.

She would play the sport alongside her literary career into her 50s.

CIVIL SERVICE AND RETIREMENT

She was also a teacher and she became head of the department of English and Social Studies at the Yaba College of Technology.

Mabel was also a broadcaster and she won the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) Artiste of the Year award in 1977.

She eventually retired from public service in 1989.

Femi Segun, Mabel’s first son, was married to Yeni Kuti, the daughter of Fela, the legendary Afrobeat pioneer. Femi died after injuring his spinal cord in a powerbike crash in 2014.

Mabel is survived by other children and grandchildren.

Add a comment