Just when the wave of change was sweeping across the continent, pulling down dictatorship in Libya, Egypt, Tunisia, among others, Robert Gabriel Mugabe pledged to firm up his stay in power. “I will be there until God says come.. as long as I am ,alive I will head the country, forward ever, backward never,” he had told his audience at the African Union summit in 2016.

Six years earlier, Muammar Gaddafi’s 40-year reign had been cut short; the following year saw the exit of Hosni Mubarak, who had ruled Egypt for 30 years and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, whose word was law in Tunisia for 24 years but for the then 92-year-old veteran, only death – not the people’s revolt – could end his stay.

To mention the country Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia) immediately brings to mind, the name “Mugabe”. The sharp mental linkage goes beyond the similarity in the last syllable of both nouns but the relationship between the country and the personality. Mugabe’s name will forever remain in the history of Zimbabwe.

Born on February 21, 1924, in a Roman Catholic mission near Harare, Mugabe was educated by Jesuit priests and worked as a primary school teacher before going to South Africa’s University of Fort Hare, then a breeding ground for African nationalism. Nelson Mandela studied there, as did Oliver Tambo, Julius Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda. After his study at Fort Hare, Mugabe taught for a few years — in northern Rhodesia, and then in Ghana, where he met Sally, his first wife.

Advertisement

The story of Mugabe, who spent 10 years in prison when his country was under colonial rule, did not end like independence heroes such as Nelson Mandela of South Africa and Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria. His death in Singapore on Friday brought to an end to the story of a man whose life story has been told with mixed reactions.

POLITICAL PRISONER

Advertisement

To several people, Mugabe was a despotic leader with hatred for the west, particularly Britain. But little did people know that Mugabe’s hatred didn’t occur overnight. He considered himself as a victim of “harsh colonialism and white supremacist identity politics”. As a freedom fighter, he began his political and activism career on his return to Zimbabwe in 1960, when he joined the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU), which was led by Joshua Nkomo and left in 1963 to form the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). In 1964, he was arrested for “subversive speech” against the predominantly white government and imprisoned for a decade during the Ian Smith’s brutal regime.

While in prison, Mugabe’s three-year-old son died of malaria, but the Smith-led colonial government denied him permission to attend the burial of his son. Mugabe would later allow Smith to serve as a member of the Zimbabwean parliament, a powerful gesture of forgiveness and reconciliation. But then, historians claim that his denial to attend his son’s burial played a part in explaining Mugabe’s subsequent bitterness.

In 1974, Smith, Rhodesian prime minister at that time, allowed Mugabe to leave prison to attend a conference in Zambia (formerly Northern Rhodesia). Mugabe instead escaped back across the border to Southern Rhodesia, assembling guerilla trainees along the way. Since his escape from prison, the life of the Mugabe was full of struggles in various forms.

FROM FREEDOM FIGHTER TO DICTATOR

Advertisement

After Mugabe’s escape from prison in 1974, he rose to the top of the powerful Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army, known as the “thinking man’s guerrilla” on account of his seven degrees, some of which he earned behind bars. The infighting against the colonial rule which was at times violent, forced Smith to the negotiating table, which led to the Lancaster House Agreement in London. It was there that the United Kingdom brokered talks between Ian Smith’s Rhodesia and the resistance to white rule. The talks led to the roadmap for an independent Zimbabwe.

After the agreement, elections was held in February 1980 to signify the independence of Zimbabwe. Mugabe’s ZANU, which merged with the Patriotic Front to create the Zanu-PF, won the election by a landslide, leading to his emergence as prime minister of Zimbabwe. He ruled the country as a two-time prime minister for seven years. After a disagreement between ZAPU and ZANU, Mugabe and Nkomo agreed to merge their parties and focus on the country. The office of the prime minister was dissolved and Mugabe emerged as president in 1987.

In his early years, he presided over a booming economy, spending money on roads and dams and expanding schooling for black Zimbabweans as part of a wholesale dismantling of the racial discrimination of colonial days. With black and white tension easing, by the mid-1980s many whites who had fled to Britain or South Africa, then still under the yoke of apartheid, were trying to come home. It was not long before Mugabe began to suppress challengers, including Nkomo, liberation war rival.

Faced with a revolt in the mid-1980s in the western province of Matabeleland that he blamed on Nkomo, Mugabe sent in North Korean-trained army units, provoking an international outcry over alleged atrocities against civilians. Although the state did not bother to count its victims, conservative estimates put the death toll at 8,000 people, while others say it was closer to 30,000.

Advertisement

FUNNY BUT FEARLESS

Advertisement

To some people, Mugabe will be remembered for his political sarcasm and ideologies. Although, he was often denounced as a power-obsessed autocrat who would stop at nothing to clinch unto power, Mugabe used his power directly in saying no to what he considers wrong. He portrayed himself as a radical African nationalist competing against racist and imperialist forces in Washington and London.

Speaking at the United Nations General Assembly some years ago, Mugabe likened Unites States President Donald Trump to the biblical Goliath, advising him to blow his trumpet in the right direction.

Advertisement

When he featured on Hard Talk, a BBC programme, in 1997 he was asked when he would relinquish power and he responded: “Go and ask the Queen of England that question.”

He had also spoken against traditions alien to the African culture. While rejecting homosexuality, he had taunted one time US President Barrack Obama, seeking his hand in marriage.

Advertisement

He loathed homosexuality and did not mince his words in saying it. Mugabe said gay people are lower than “pigs, goats and birds and they should go to hell”.

“Let Europe keep their homosexual nonsense there and live with it. We will never have it here. The act [of homosexuality] is not humane,” Mugabe had said at a rally in 2013.

Any diplomat who talks about homosexuality will be kicked out. There is no excuse and we won’t listen to them.”

At the 26th African Union Summit in Addis Abbaba, Ethiopia, despite local and international criticism against his government and party, Mugabe told leader to Europe to “shut their mouth” when discussing issues pertaining to him and his country.

“Your party is in power for too long, you must now allow another party t take over and that was coming from Europe. Tell them to shut their mouth,” he had said.

CONTROVERSIAL SEIZURE OF LAND FROM THE WHITES

In 2000, Mugabe commenced a land reform, which led to the seizure of white-owned farms for the resettlement of poor black farmers, without compensation for the whites. The former president said the policy was needed to transfer productive land into the hands of black Zimbabweans. The policy led to the fall of agricultural production as many of the black farmers were inexperienced. It also led the country with a net importer of staple maize grain between 2000 and 2016. The land reform, which according to reports, led to the death of few whites, strained the country’s relationship with Britain and other western countries. Many white commercial farmers fled the country for the fear of their lives. It also led to the withdrawal of international economic partners and investors.

WELL EDUCATED PRESIDENT

With seven university degrees, Mugabe, who was born to a carpenter father, is one of the most educated persons that has ever held the helm of affairs of a country across the world. He holds a bachelor’s degree in Arts and Education from the University of Fort Hare in South Africa and earned multiple graduate degrees by correspondence while he was in prison, including a Bachelor’s of science in Economics from the University of London and two other law degrees. His degree of education contributed to rise at powerful Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army.

Writing in a 2007 cable released by WikiLeaks, Christopher Dell, former US ambassador to Harare, reflected the views of many on Mugabe when he said “to give the devil his due, he is a brilliant tactician.”

MARRIED TO HIS SECRETARY

Mugabe was first married to Sally, a Ghanian. Until her death in 1992, she was described by many as the only person capable of restraining him. Mugabe started his romance with his then secretary, Grace, while his Ghanaian wife Sally was dying. The affair started while Mugabe’s wife Sally was struggling with renal complications.

“Grace and I never dated either, I was just introduced to her and I said to myself she is a beautiful girl,” he narrated.

“So she came as a secretary and they were many of them, I just looked at them and then it was love at first sight with Grace. Then I said to her one day, I love you and she didn’t respond. I then grabbed her hand and I kissed her. She didn’t protest or refuse and then I said to myself now that she has accepted to be kissed, it means she loves me.”

Mugabe’s daughter, Bona, was born two years before Sally died in 1992. Grace later gave birth to Robert Junior. They went on to have their third child Bellarmine Chatunga the following year.

REPLACED BY HIS ALLY

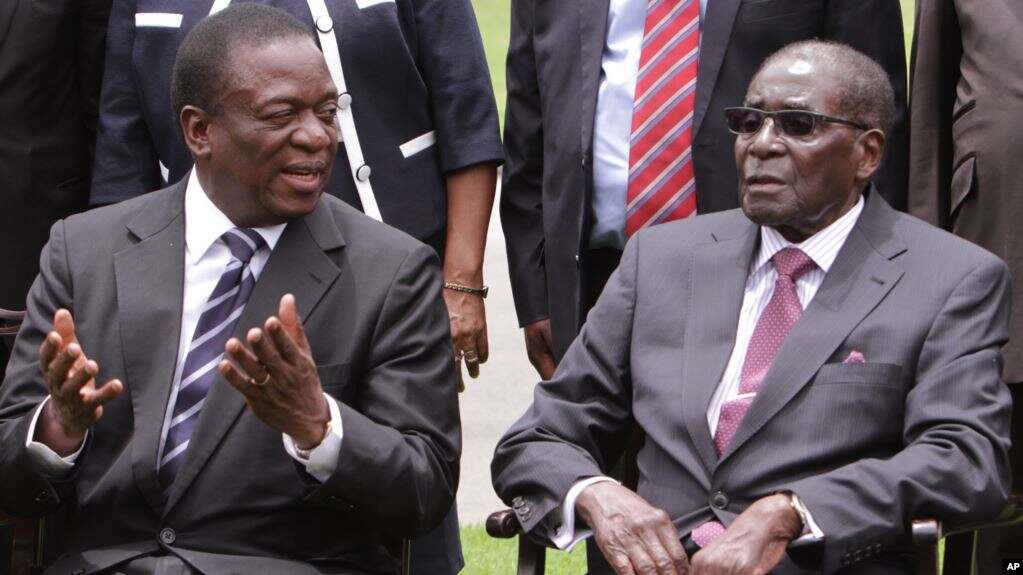

Mugabe, who had ruled Zimbabwe since independence in 1980, was ousted through a military coup in November, 2017. Before then, Grace, his wife who had warmed her way into his heart, indicated interest in succeeding him and Emmerson Mnangagwa, former vice president, who was perceived as a stumbling block was sent out of the way. He was accused of disloyalty and sacked on November 6. Eight days later, the military struck in form of a coup –despite Mugabe’s claim that no coup can remove him from power.

Although his resignation was celebrated by millions of citizens in the country, for Mugabe, it was an “unconstitutional and humiliating” act of betrayal by his party and people, and left him a broken man. He stepped down under pressure from Mnangagwa’s allies in the army in November and quit as parliament began a process to impeach him, triggering wild celebrations in the streets.

In an interview with South African state broadcaster SABC, Mugabe said he never expected Mnangagwa to turn against him.

“I never thought he whom I had nurtured and brought into government and whose life I worked so hard in prison to save as he was threatened with hanging, that one day he would be the man who would turn against me,” he had said.

Perhaps he did not forgive Mnangagwa till he died, Mugabe banned the Zimbabwean president from his funeral.

‘RESURRECTED MORE THAN CHRIST’

On his 88th birthday, Mugabe said he had died many times and resurrected, unlike Christ who did once.

“I have died many times — that’s where I have beaten Christ. Christ died once and resurrected once,” he said.

In 2016, when he was 92-years-old, he said he would contest the 2018 election and would remain in power till “God says come”. A year after, when rumours of his poor health condition spread, the former president seemed to have developed a change in his ideology towards life. He admitted God’s control of ones life, but still hinted that the power he has would remain with him.

“It is not always to predict that although you are alive this year, you will be alive next year. It doesn’t matter how healthy you might feel but the decision that we continue to live and to enjoy life is that of the one personality, we all call the almighty God,” he said.

In his last years in office, Mugabe’s authority dwindled. His age and health condition told on his actions. He was no longer in charge. His house arrest and trips to Singapore for medical treatment made the power giant a mere observer of the political stage. Mugabe was reduced to a figurehead. The power giant could no longer stand. But now, God has finally said “come” but the power had left Mugabe before he answered God’s calling.

Add a comment