BY KAZEEM FAYEMI

Abosede Olayemi Sophie Oluwole was born in 1935 in Igbara-Oke, Ondo state into an Anglican family. Her father was baptized in 1912 while her mother’s baptism came in 1915 shortly before her marriage. Both parents were from Edo state. Contrary to popular opprobrium that Oluwole is a Yoruba given her prominence as a leading figure in Yoruba Philosophy, she is indeed an Edo person by virtue of ancestral lineage. Her being born and bred in Igbara-Oke was a result of her father being born and lived there.

Oluwole’s grandfather came from Benin in about 1850 and was indeed a high ranking official in the Oba’s palace in Benin. Her paternal grandmother too came from Benin, a daughter of a Benin governor in Ogotun. Both her parents were established traders. Her mother, who was an expert in tie and dye, was also a professional weaver and an astute trader in Igbara Oke market. Her father was an accomplished trader, shuttling between Lagos and Igbara-Oke and from Igbara-Oke to Onitsha.

Being an Edo woman, Oluwole understands the Edo dialect though could not speak it fluently. It is therefore tempting to regard her of being more of a Yoruba person, especially in the light of the origin and source of her name than regarding her as an Edo person. Without necessarily recurring to her surname after marriage, Oluwole, both “Abosede” (a girl born on a Sunday) and “Olayemi” (I deserve wealth) in her names are of Yoruba extract and syntax. The “Sophie” in her name has a complex entry. Neither was she named “Sophie” at birth by her parents or grandparents nor did she choose and foist it on herself. The name came about long before she could even fathom the meaning.

Advertisement

HER EARLY EDUCATION

She earned the name “Sofia” (in its original spelling before later spelt “Sophie” as a matter of choice) around the age of eight when she was about to be baptized. The name was given to her by a headmaster of the community school in Igbara-Oke who was a friend of the family. He came about “Sofia” as a result of his assessment of Abosede Olayemi as a clever girl. This second naming by the headmaster was significant in Oluwole’s life because shortly after the baptism, she ended up living at the headmaster’s place. From here, Sophie attended St. Paul’s Anglican Primary School, Igbara-Oke, where she had her primary education up to standard VI. She proceeded from here to Anglican Girls modern school, at Ile-Ife in 1951. In 1953, she enrolled at the Women Training College, Ilesha, where she finished with a class IV certificate in 1954. With this excellent result, she became a qualified teacher.

Oluwole began her teaching career, first at Ogotun and later in Ibadan. Though this career was truncated when in 1963, she decided to travel to Moscow along with her husband, who was on scholarship. At Moscow, Sophie’s intention was to study Economics, which was mainly thought in Russian Language. Due to her deficiency in the language, she enrolled at Moscow State University for a year preparatory class. Her time of completion of this course in 1964 was coincidental to the period her husband decided to leave the Soviet Union because of the difficulty of coping with the Russian Language. The implication of this was that she had to leave with him and the dream of studying Economics at Moscow was unrealized.

Advertisement

From Moscow, Oluwole left for Germany in 1965 while her husband went to the United States to continue his studies. In Germany, she proceeded to the University of Cologne. Because she did not have “A levels” before she left Nigeria, and since her certificate of preparatory course at Moscow State University was not recognized in Germany, she was unable to gain direct admission to a German University. So, in Germany, she had to do another preparatory year. Her performance at the University of Cologne, which was excellent, earned her a full scholarship in Philology. But instead of honouring the scholarship, Oluwole decided to go to the United States to meet her husband, with whom she had three children in Nigeria before their academic odyssey abroad. Oluwole left the United States for Nigeria in 1967. But before returning home, Oluwole had ensured that she gained admission to a university in Nigeria in order to continue her education when back home.

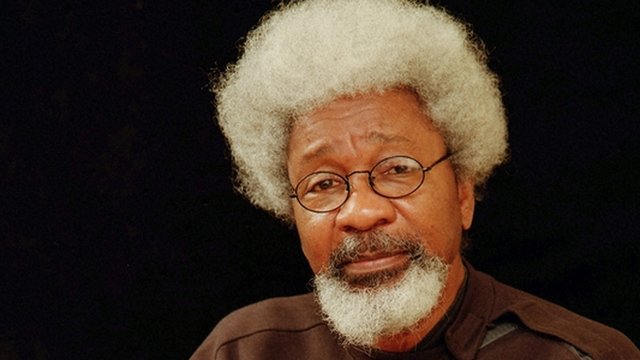

THE FEAR OF SOYINKA

At this time in Nigeria, Oluwole’s thinking was not even that of studying Philosophy. She got admission into a B.A Education programme with English as her main subject at the University of Lagos in 1967. She eventually abandoned English for Philosophy because of the predominant phobia of Prof. Wole Soyinka, who many regarded at that time as an academic monster in the Department of English, UNILAG. Her attraction for Philosophy began to grow because of her innate capacity for looking at issues critically and as a person given to prolific expressions. She had her first degree in Philosophy in 1970, coming out top of the class with a Second Class Upper Division.

It is interesting to note that throughout her first degree education, she was never introduced to African philosophy. This was not advertent but because her teachers were mainly trained in the West and had to take the class through Greek philosophy, British philosophy and German philosophy. Oluwole obtained her Masters degree in 1974 at the University of Lagos. It was at the point of writing her M.A dissertation that J.B. Dankwa (Jr.) mentioned African philosophy to her hearings for the first time.

Thus, Danquah got her interested in African philosophy but Danquah’s interest was on Egyptology, which traces the origin of African philosophy, and even Western Philosophy to Egyptian writings and thought. But Oluwole had some disquiet and reservations with this view. Her concern was not to controvert the popular Egyptological view that earlier Greek thinkers came to Egypt to study Philosophy, steal or borrow the Egyptian philosophical thought as the case may be. Nor was she concerned with investigating the Africaness of the Egyptian civilization or not.

Advertisement

Her concern was motivated by the question: “If the Egyptians were black and they studied Philosophy first, what happened to the original people, the people who initiated Philosophy?” Are there residues of the original African thought, that predated the advent of Christianity or Islam? These and other related questions agitated her mind. In seeking answers to this string of questions, she thought that her M.A dissertation would provide a veritable platform.

HOW HER DREAM TO RESEARCH ON AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY WAS ABORTED

Unfortunately, her dream to research on African Philosophy was aborted simply because there was nobody to supervise her then in the Department of Philosophy, University of Lagos. There was nobody with a qualification in African Philosophy, So, her area of research now changed from African philosophy to philosophy of language in Western philosophy. The title of her M.A dissertation was “An Introduction into the Relationship between Transformational Grammar and Logical Analysis.” Her burning desire to research in African Philosophy was not let loose even at the level of her Ph.D thesis. Initially, when she started in 1977, she wanted to write on “The Rational basis of Yoruba Ethics” but her proposal met a brick-wall upon presentation to her supervisor. Two reasons were responsible for this denial of her area of research interest.

One was the fact that her supervisor never believed in the existence of a corpus of thought that can be identified as African philosophy. Two, the supervisor had expertise in Greek philosophy and was not trained in African philosophy. So, Oluwole ended up writing her thesis on Meta-ethics and the Golden Rule. Though not interested in researching on Western philosophical theme, but by prudence of circumstance and the need to show her capacity to research on any philosophical issue, she took the topic up and got through with her Ph.D thesis in 1984. With the successful defense of her thesis, Oluwole broke the ice by being the first Ph.D in Philosophy awarded by a Nigerian university. Upon completion of her Ph.D, there now came the freedom to research and write on African philosophy, which had always been her area of interest since 1974.

Advertisement

Based on the above background, a discussion of the theoretical and circumstantial influences on Oluwole’s Philosophy is worth doing. The influences on Oluwole’s intellectual development can be gleaned in three ways. First, the influence of her teacher, Errka Maula, Ph.D, instigated her interest and disposition to the analysis Tradition of Philosophy. Second, her critical encounter and reactions to the teachings of A.G. Elgood, her teacher also, influenced her into being an unflinching defender of African culture. The third influence on Oluwole and which actually has a lasting imprint on her orientation in African philosophy is her reading by chance, Abimbola’s classic, Awon Oju Odu Mereerindinlogun (1977). Each of these points of influences on Oluwole deserves some expatiation.

Maula, her undergraduate teacher with multidisciplinary certifications (B.A. English and German Literature, M.SC Mathematics and Ph.D Philosophy) was unavoidably addicted to reading between the lines in search of conceptual clarity and ingenious contributions of the opinion(s) of his students on the issue at discourse. On the account of Oluwole, meeting up the conceptual and critical rigour of Maula led to a fundamental challenge that forced her to think and write lucidly.

Advertisement

A. G. Elgood was another philosopher, who had a tremendous influence on the philosophical formation of Oluwole. On the account of Oluwole, Elgood, who was the Head, Department of Philosophy, University of Lagos, 1966 session, taught the 200 level class, Philosophical Analysis. In his discussion and explanations of doctrines such as fatalism, Elgood, according to Oluwole, made some derogatory comments about African thought, which Oluwole critically objected to and resisted against in the lecture room. Elgood, on the authority of Oluwole, was quoted to have maintained that Africans are fatalists. The basic argument of fatalism is that “whatever will be, will be, no matter what you do.” To illustrate Elgood’s point, fatalism expresses that if A was told he would die at “point 2” at time “T” and A decides to be at “point 3” at that time “T” he would still die at “point 2.” Seeing this as a castigation of African culture and African peoples, upon graduation, Oluwole was led into thinking that most of what have been said about Africans are suspect.

As a consequence, Oluwole took as imperative, a counter reaction and response to the claims of her teacher on fatalism and its representations in African beliefs and traditions. The point of influence of Elgood on Oluwole was that as she became suspicious of every external (i.e non-African) remarks on Africa and her peoples, inadvertently, Oluwole becomes a systematic defender of African cultures. Oluwole was one of Africa’s foremost philosophers who worked extensively in the area of oral tradition as philosophy, and made original and uniquely perceptible contributions to the exposition of ancient Yoruba philosophy and African philosophy in general.

Advertisement

The intellectual leap of Oluwole’s philosophical trend into the study of Yoruba Ifa oral tradition was accidentally occasioned by her daughter, Funke Geshide. Geshide read Yoruba and Religions at the University of Lagos and by the time she got married, substantial parts of her book collections were left on her mother’s (i.e. Oluwole’s) book shelf. One of her classic collections was Awon Oju Odu Mereerindinlogun written by the prominent Yoruba scholar, Abimbola (1977).

Though not necessarily fascinated by the title of the work, Oluwole, who is indiscriminate about the materials she reads, had the intent of reading a few pages of the book. But to her utter surprise, by the time she read through verses two, eight and nine of Ejiogbe, and verse seven of Owonrin meji in the book, she was already a convert of the study of Ifa Corpus. The reason for her research paradigm shift from mainstream Western Philosophy to the study of Yoruba Oral Tradition was because of the fundamental issues of human existence abundantly discussed in Ifa corpus. This shift, however, brought with it, a serious challenge for Oluwole. The verses in the Ifa corpus originally exist in complex linguistic style characteristic of most ancient literatures. In surmounting this challenge, Oluwole settled for the learning under seasoned tutors in Yoruba language.

Advertisement

HER WORKS

Against this background, Oluwole quickly established herself as a leading figure in the budding field of African Philosophy. Between 1989 and 1996, she rolled out five books on African philosophy, Readings in African Philosophy (1989), Witchcraft, Reincarnation and the God Head (Issues in African Philosophy) (1992), Womanhood in Yoruba Traditional Thought (1993), Philosophy and Oral Tradition (1995) and Democratic Patterns and Paradigms: Nigerian Women’s Experience (1996). In 1997, focusing on the essentials of African studies and her determination to provide good reading texts to the Nigerian students, especially on African studies, Oluwole edited two volumes of the book of reading, The Essentials of African Studies. Still in 1997, Oluwole was also the editor of the classic volume on Women in the Rural Environment; a publication sponsored by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation.

For the sake of illustration, a review of her frequently cited works on Witchcraft, Reincarnation and the God Head and her Philosophy and Oral Tradition is in order. Though a collection of her essays and lectures from 1976 to the early 1990s, Witchcraft, Reincarnation and the God Head discusses some overlapping thematic and perennial issues in African Philosophy as well as non-African specific cum political issues. With reference to that of the culturally specific themes, Oluwole engaged herself with some questions which play an important part in everyday African life: the analysis of magic, the belief in fatalism and reincarnation, the belief in witchcraft, the belief in God, and the principles of Yoruba morality.

She emphasized that the phenomenon of witchcraft should not be approached from a rigid, scientific perspective which excludes anything that does not fit within the system. Mysteries are phenomena which are not yet understood and explained, however, this does not mean that they can never be understood; there is still the possibility of an explanation in the future (Oluwole, 1992: 19). Science should not simply ignore them or declare them not real, but should analyse and document these phenomena instead, attempting to understand how they operate. She discussed also the problem of fatalism, and the rational basis of Yoruba ethics.

The non-African specific and essays on political themes are “The Concept of a Universal God,” “Institutional Neutrality and Academic Freedom” and “Democracy or Mediocrity?” Her essay on institutional neutrality is a critical reaction to an earlier work by F.A. Adeigbo (1985) on “Neutrality Arguments and Educational Relevance’: ‘The Chess Game Analogy”. On academic freedom, she proposed that the claim of the universities for academic freedom cannot be separated from the issue of the individual neutrality of every single academic.

The core of academic freedom and intellectual integrity is simply indifferent to the results of investigations. Provided that political freedom is exercised under the umbrella of academic freedom, the engagement of political institutions is justified in Oluwole’s opinion (1992: 103). Her analysis concerning “Democracy or Mediocrity” is provocative. Democracy is based on universal suffrage and eligibility, but, whilst the right to vote as a basic political right is beyond question, universal eligibility is a little more problematic. Humans are different in both qualities and abilities; consequently, not all human beings are equally qualified to exercise power. Thus, the problem of modern democratic societies is their neglect of the “specification of the qualities which justify the appointment of a member of the state to hold the reins of government, to stand in for the demos, to organize, plan, administer and regulate the entire society of a people who entrust their rights to run their lives the way he deems best” (Oluwole, 1992: 120). Her last essay in the volume, “Africans and the morality of Nuclear War” is an African perspective and consideration of a universal and non-cultural specific ethical issue, that of nuclear weaponry and war. Her argument is that “if the cry against Nuclear war must be presented by philosophers on the platform of morality, then we must start on an axiom that condemns all wars- conventional or nuclear” (Oluwole, 1992: 137-138).

Using extant sources of oral tradition, Oluwole employed heuristic criticism to controvert what was then an established cliché among scholars: that oral traditions such as proverbs are folk or pseudo Philosophy. Instead, she established that some oral texts qualify as Philosophy and that what makes them Philosophy is not the analysis per se done on them by a professional philosopher (which is the popular belief in some quarters), rather, what qualifies them as Philosophy is inherent in them. Thus, Oluwole concluded that contrary to the widely accepted thesis of Wiredu, Hountondji and others (to the effect that “a student who wishes to know the Philosophy of a Western philosopher goes directly to such a person or to his/her work and not to poor peasants or fetish priests” (Wiredu, 1980: )), “the babalawo and the priests who are custodians of oral traditions are philosophers because they can criticize and interpret both old and new principles of ideas”.

But besides the cultural and historiographical significance of her study on ancient Yoruba philosophy as well as the scientific import of her thesis on witchcraft, the future philosophical implications of Oluwole’s new and daring thesis on Socrates and Orunmila as two patron saints of classical philosophies with great affinities at the level of ideas and history (Oluwole, 2007) is scholarly inviting. Those looking towards and indeed espousing Greek philosophy as the sole model and foundation of Western philosophy to the denigration or outright denial of ancient African thinkers are urged to begin to seriously rethink the cogency of their positions by archeologically researching into traditional African oral sources for latent discoveries of classical African philosophers.

Another aspect of the Yoruba philosophy that intrigued Oluwole is the Ifa corpus, which is the storing house of Yoruba knowledge. Her foray into the philosophical basis of Ifa, which had hitherto been conceived purely as a divination system, began with her discussion of “African Philosophy as illustrated in Ifa Corpus” (1996). On the basis of the evidence from two verses from Ifa corpus – Oyeku meji and Oworin meji, she demonstrated how some ancient African literary pieces qualify as specimens of strict philosophy.

In a related development, Oluwole has a number of works that define her scholarship in proverb as philosophical studies. In her paper, “Science in Yoruba Oral Tradition” (2007) and “Proverbs as Expressions of African Philosophy” (2010), Oluwole engaged in a heuristic analysis of proverbs to show that ancient African thinkers were rational, scientific and philosophical in the strict sense of the usages of the term, science and Philosophy.

Her truly remarkable professional career and achievements reveal her enviable contributions to the enterprise of philosophizing in Africa. An incredible scholar by all standards, Oluwole was one of the most prominent Nigerian philosophers in the world. The breadth and the depth of her scholarship are not only impressive but also widely acknowledged. In this regard, she wa a recipient of many awards and honours from institutions in Africa and beyond. She received the prize of Bundesstudentenring, West Germany 1965-1967, University of Lagos Postgraduate scholarship award 1971-1972; she was the first recipient of Jean Harris award for outstanding contribution to the progress and development of women in society by Rotary International in 1997; Emotan award for women achievers, 2001. It is not an overemphasis that she has contributed relentlessly to the course of women, and humanity in general.

She authored books on some extant issues in African Philosophy. Being the first female professor of African philosophy in Nigeria, the Philosopher-Queen is a household name in the enterprise of Philosophy in Nigeria. With seven books (both authored and edited), nine book chapters, sixteen journal articles and some book reviews to her name, Oluwole is wizardly in Yoruba language. Not many Nigerian scholars of our time can lay claim to such contributions to scholarship of the first order. Oluwole’s scholarly productivity is phenomenal, especially when viewed from the Nigerian academic environment which is frustrating enough to academic proclivities because of lack of enabling facilities. Being a philosopher is her profession; writing, publishing and speaking at invited public gatherings are her passions; and living up to what she preaches is a habit.

Fayemi, Ph.D, is a postdoctoral research fellow, Department of Philosophy, University of Johannesburg, South Africa