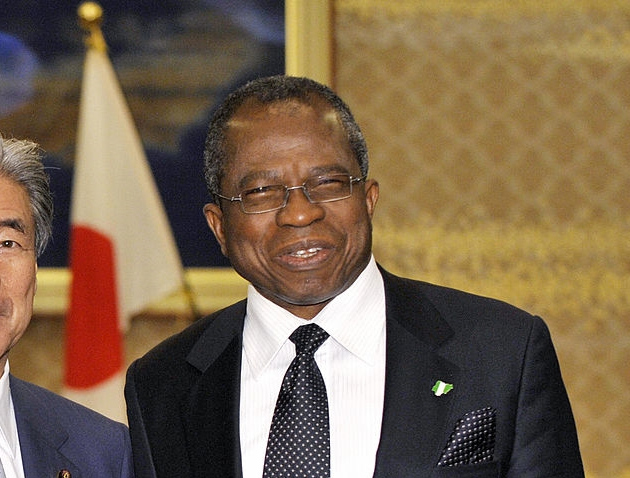

Someone rightly observed that perhaps Chief Ojo Maduekwe is one of the most misunderstood Nigerian politicians of the last three decades. This is true. It is also true that he is one of the under-reputed politicians in Nigeria. Yes, many Nigerians have expressed shock at his death and hundreds of tributes have been penned by many illustrious and famous persons in and outside Nigeria, it is still true that Ojo Maduekwe deserved more than the good reputation he enjoyed while alive. Perhaps, now that he is dead the rest of his compatriots will come to better understand the mind and legacy of a hard-to-forget politician. It is now the responsibility of those of us, his colleagues and progenies, to present him, in all his weaknesses and strengths, to the people.

One distinction of Ojo Maduekwe, even as a politician, is that he was primarily a thinker. He loved ideas and tasked himself to think clearly about the issues of the day. Chief Ojo Maduekwe was, amongst other things, arguably Nigeria’s foremost and most authentic example of the intellectual in politics. Perhaps, we don’t have his likes anymore. May be, we can only point to the First Republic for the likes Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, etc. In the Second Republic, we could point to the likes of Dr. K.O Mbadiwe, Mokwoyo Okoye, Ebenezer Babatope. Contemporary Nigerian politics is denuded of the intellectuals who are not ghosting around politics but primarily engaged in realpolitik. Of course, we still have few intellectuals moving to and fro the seat of power. But they come and go more as technocrats and less as politicians. None of these intellectual tourists in power have held on like Ojo Maduekwe, active in the statecraft and politics, for more than two decades.

As a seminal public intellectual, he was prolific and creative in ideas. I always marveled how he was able to produce such quality and quantity of seminal essays and presentations on some of the deepest issues in political and legal philosophy, and still kept up with the daunting challenges of partisan politics. It will be such a heck of a job to live with politicians who detest ideas and its inconveniences and still love ideas the way Ojo did. From a firsthand experience I can imagine what an inconvenience Ojo’s embrace of ideas was to his colleagues. I remember when he introduced me to a former Governor of Imo State to support me to run for Senate. Ojo had promoted my candidature because, as he put it, “this is the smartest guy I have met”. The Governor hailed me but shrugged off the suggestion, and said, “my leader, you know I don’t like intelligent people’. That governor could be speaking for the rest of the tribe. Politicians may dislike intelligent people as that Governor put it. Ojo was different. Ojo deeply liked intelligent people. How did Ojo keep the company of the intellectually laggard and yet found time to produce the works of such intellectual depth?

How did Ojo manage to be intellectually active and political engaged at such level? The answer is simple: Ojo was blessed with very good brains; good brains made better by continuous reading. The biggest joy of travelling with Chief Ojo Madukwe as foreign minister was the assurance that at every city worthy a name the first port of call would be a bookstore. It was as if a bookstore was a sanctuary to Ojo. A sanctuary from the numbing blabbing of politics. The only problem was the ever present risk that Ojo could be so absorbed in perusing mounds of books and missed the connection flight. It is difficult to draw Ojo away from the nectars of book. He was a nightmare to a protocol officer. I could trust Ojo to tell me the latest offerings in neuroscience, literary criticism, politics, leadership and management. As a frequent traveler his luggage consisted more of books and magazines and less of clothes and other personal effects.

Advertisement

Ojo’s lectures read more like academic treatises. Even as he has the support of highly talented assistants, Ojo often wrote his lectures and speeches. When he was helped to write some he would personally write the ideas and insights he wanted to communicate and left his aides to simply turn them into drafts. How he could write such extended essays and still meet the tight schedules of a Minister of Transport or a Foreign Affairs Minister remains a surprise. Of course, he was blessed with great energy. He was always bustling with energy as he breezes through many assignments. Working with him as his Special Adviser, it was difficult seeing Ojo walk leisurely to any activity or event. Like Okonkwo in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Ojo sprinted as if a spring was affixed to his feet. To be that productive one would need not just good brains but also health bodies. Ojo was an exercise freak. He kept to the rituals of early morning workout. Just as he nursed his brain Ojo built up his energy and physicality through exercises.

Ojo Maduekwe straddled many roles, as a lawyer, a social activist, a public officer, a politician and a church leader. But it is in his role as public officer and politician that he established a better known legacy. Many people forget that before he ventured into politics Ojo Maduekwe practiced as a lawyer in Lagos. As a lawyer Ojo used law as a tool for social emancipation. He was not the bread and butter lawyer. He envisioned a bigger role for law, a role that conceived law as a logical conversation with society as to the possibilities of social and individual redemption. To him, a vocation as a lawyer is a vocation of social engineering. Little wonder he embraced civil rights lawyering with a passion. I owe recollection of this aspect of his life to the former Chairman of the Nigerian Human Rights Commission (NHRC), Dr. ChidI Odinkalu, who recollected how Ojo as a young lawyer would drive around prisons and police cells helping indigent victims secure justice. As a lawyer he was committed to the ideals of public interest. He would also be remembered as a lawyer who made himself available to mentor many young lawyers. For law students with an experience of student activism, Ojo’s law office in Western House, Lagos, was a resort for intellectual fecundation.

In his fairly long life on earth, Ojo Maduekwe ventured into many spheres. But one strand holds together the variegated shards of his experience: the unrelenting commitment to public service. Whether as a lawyer, a politician or a public officer, Ojo fixed his mind on how to promote the public good. In spite of his esoteric ideas Ojo was a person of this world. He cared deeply about the concrete conditions of human life and society. As an intellectual, his ideas are subjected to the pragmatism of what would uphold public order and social development. As a political actor, his deeds are ennobled by the idealism of what is good for the society. He was the typical public spirited person who would always ask himself what is in the public interest. It is on such persons as citizens that the great edifice of democracy is built. Without public spiritedness we cannot sustain the culture and institution of democracy. Both Cicero and John Locke will find in Chief Ojo Maduekwe a worthy citizen of the polis.

Advertisement

Ojo Maduekwe’s life paints a varied tapestry of a family man, a politician, a public servant, a theologian and a public intellectual. These diverse pieces of biographical sketches or patches of recollections are held together by a simple thought: Ojo lived his life in passionate pursuit of excellence. Quite early in his political career Ojo coined the word “Mekaria’ as his political moniker. The commitment to the pursuit of moral, intellectual and spiritual excellence defined Ojo in all his entire life undertakings. The sad thing is Ojo’s commitment and exemplification of excellence is often overlooked or dismissed by his countrymen and women. This seems to be the fate of many persons of excellence. Many decades ago, a Russian writer is reported to have lamented that it was the devil’s trick to be born in a country where neither talent nor soul was appreciated. If Nigeria was nothing close to such a country Ojo’s life would have been better celebrated by his country men and women.

Ojo was fated to be either deeply respected or gravely despised. He was very passionate and unrelenting in embracing controversial ideas. In a clime where conformity to sterile conventions and group-thinks is a cardinal virtue, to embrace controversial ideas in the manner Ojo did is bound to generate so much angst from those wedded to conventions.

It is also one of Ojo’s fate to be passionately admired and loved by those who started as either enemies or, at least as despisers, and later transform to friends when they come close to the ‘Mekaria’ factor. I am one of such ‘turncoats’. When Ojo served as President Obasanjo’s Minister of Tourism and Culture (and later as Minister of Transport) I was one of those who did not like him much because of the perception that he was committed to defending everything that President Obasanjo did in office. Obasanjo had developed a reputation for reckless egocentricity and pugnacity. There was no love-lost between him and the civil society. Dislike for Ojo was one of the collateral damages for being so much beloved by President Obasanjo.

One day I met Ojo in person and all the bile dropped into the fire. His presence was magnetic, and we struck a deep friendship and comradeship that resulted in my becoming his Special Assistant when he was appointed the Minister of Foreign Affairs. What cemented our friendship was Ojo’s real devotion to ideas and his passion for books. It happened that we shared common admiration for similar theologians and philosophers. He had read most of the leading ancient and modern political philosophers and we often engaged in analysis and critique of these philosophers.

Advertisement

I have a tendentious test for would be great public leaders: do they love books and respect ideas. If a politician or political leader cares less about ideas and books, or still consider them a little irritant, then it is as sure as day following night that she would end as a bad leader. I admit that the assumption behind this test is not empirically verified. But it is a useful rule of thumb. There are many who read books for either the pleasure of reading or the burden of responsibility. Ojo read because he loved ideas and considered the intellectual life a pleasurable engagement. In Ojo, the saying that leading and learning go together found embodiment.

As I continued in the fellowship of breaking bread and sharing ideas with Ojo I became an acolyte. To be Ojo’s friend or acolyte there was no requirement of accepting the ideas that animate his passionate and controversial politics. What is required is just the aptitude to subject opinions to rational critique and to continuously seek higher truths. Ojo’s abiding creed was the pursuit of knowledge. I think he had too much respect and devotion to ideas such that no matter how irreverent and contrary a man of ideas may be, Ojo would gladly seek his friendship.

I recall an incident that happened when he was the National Secretary of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP). It was at the height of the infamous attempt to amend the constitution to give President Obasanjo three terms as President contrary to the Constitution. The debacle is dubbed the ‘Third Term Agenda”. Although Ojo claimed not to be privy to any Third Term Agenda as the party secretary (and I believed him) the PDP rallied around the President and the supposed Third Term Agenda. This was the beginning of my friendship with Ojo. He knew I was Special Adviser to then Senate President, Ken Nnamani, who had major policy and moral disagreement with President Obasanjo and would go ahead to preside the defeat of the Third Term Agenda. Of course, Ojo knew my radical tendencies and principled opposition to the agenda. He loved my description of the agenda as “audacious immorality”. Yet he sincerely sought my opinion on how he should act as National Secretary of the party in the moral and political contexts of the agenda. I advised Ojo to focus on protecting the moral capital of the party the morning after the defeat of the agenda and not get too involved in the politics of the Third Term Agenda. He seemed to heed my advice as he was not one of those who came to grief on account of the defeat of the Third Term Agenda.

On one of our usual dinner haunts to review the crisis of the Third Term Agenda, Senator Okereafor advised that Ojo should not listen to Eziuche Ubani, Abike Dabiri and myself because we are of the opposition. Ojo sternly rebuked him. Ojo told him that he preferred to listen to the views of those of the opposition than the PDP members on that matter. This was not to humor us. It was not a matter of good hospitality. It was real. Ojo welcomed all irreverent ideas as long as they are sensible and well delivered. He called them holy heresies.

Advertisement

Now let me touch on the taboo subject of Ojo’s politics. Many Igbos believe that Ojo Maduekwe did not fight the cause of the Igbos. It is one of those pardonable misunderstanding of Ojo. Unfortunately, for these naysayers, Ojo is better known for the expression “Igbo presidency is idiotic”. He had made this statement before I met him. But it had come up several times in our conversation either about the Igbo question or the Nigerian question. Ojo’s perspective is correct and sublime: Igbos want a Nigerian president of Igbo extract. In a plural society it would be preposterous to campaign for an Igbo or Yoruba president.

Nevertheless, Ojo made a tremendous error in his seemingly belligerent and intolerant response to the lexically challenged advocates of Igbo presidency. He failed the cardinal principle of political communication: connotation matters more than denotation and meaning is always contextual. He failed in a craft he was a master. This failure did not come from any animus. Perhaps, it came from a little hubris. But never from a disinterest in the subject of Igbo political survival.

Advertisement

To build on the inappropriateness of the ‘idiotic’ expression to challenge Ojo’s bona fides as an Igbo leader is totally unwarranted. Ojo was a proud Igbo man, an animated Ohafia warrior. From dressing to cosmology Ojo loved the Igbo way of life. He believed that the Igbos have a manifest destiny to contribute to the redemption of the black race. He believed so much in the Igbo genius that he was always very eager to mentor any Igbo showing signs of excellence. He never hid from any worthy Igbo cause.

Ojo’s Igbo political project was not the bigoted triumphalism of some Igbos who believe that the rest of the Nigerian ethnic landscape is nothing but an appendage to the Jew of Africa. Not at all. Ojo believed that the Igbo exceptionalism should commit Igbos to a Pan-Nigerian struggle to redefine and transform Nigeria. The current events may suggest that Chief Ojo was too sanguine and hopeful about the Nigerian project. But definitely, his idealism, or, in worst case, naivety, could never amount to an abandonment of the never-say-die spirit of the Biafran soldier. Until his death, Ojo believed that an Igbo president remained a clear possibility. But he believed that rather than isolating themselves Igbos would do better by deploying their smarts and enterprise to win the political battle for the Nigerian presidency.

Advertisement

Ojo was in public governance for more than 16 years. He had been in government in Nigeria as long as the PDP. For this reason alone, he would inevitably suffer some degree of the opprobrium poured on the PDP. Some people have uncharitably dubbed him “Any Government in Power (AGIP). They have suggested or implied that Chief Ojo Maduekwe lacked principles as a politician and could serve any government no matter how disoriented as long as it offered him an opportunity. This is false.

Many people don’t know that Ojo’s seeming conservative politics was principled. It derived from a finely constructed intellectual framework. Ojo’s politics was very ideological. If he seemed to have worked for the status quo it is because his ideological understanding of statecraft emphasized the primacy of order over freedom. This derived also in the main from his Presbyterian theology. The centrality of sin in human affairs means that the authority figure in the form of the police state should never be discounted. It is the same message retailed in William Goldings “The Lord of the Flies”.

Advertisement

In my view Ojo was a social democrat to the extent that he truly believed in the liberal ideal of personal freedom and the priority of choice over right. But, like some center of the right philosophers, Ojo was also somewhat a communitarian who believed that the edifice of liberal rights must be built on the foundations of social order. Except we protect the integrity of the state we cannot sustain liberal rights. This tended to cast him in the mold of an apologist of the state.

In history the tension between liberal politics and communitarian ideal has always been difficult to resolve. This tension manifested in how Chief Ojo Maduekwe reacted to some of the crises in Nigeria. As an intellectual of development he recognized the overriding importance of state capacity for economic and political transformation. As much as he recognized the importance of the market to drive development, he believed that the ultimate underwriter for economic and political development is a strong government. As Ojo usually said, in Nigeria there is neither a state nor a market. Therefore, you can’t talk about a market driven economy. There is no private sector as such to drive development. In the final analysis you have to summon the government to mobilize for transformation.

Ojo had a love-affair with strength. Perhaps, he got too easily seduced by leaders who manifested strength or pretended to be strong like President Obasanjo. His near adorable for strength is because of his preference for order. In his view, ultimately, for fractious African society, you need social order to guarantee liberal rights. And political order requires a strong government. This syllogism is falsifiable but it appealed to Ojo’s religious mind. Regrettably, sometimes, strong governments violate human rights. But strong governments and a regime of human rights are not necessarily incompatible.

Once I traveled with Ojo to Rome. We visited the Colosseum, the theater where the gladiators entertained the tyrants of Rome in an imperial age. It was a great, even if traumatizing sight. How did the ancients built such an edifice to satisfy their appetite for gory violence? As we were conducted around the magnificent testament to power and debauchery Ojo asked with cryptic irony whether such gargantuan construction project was possible in an era of human rights? We laughed over his observation. Of course, today, no one will believe that a King will send people across the seas from Europe to Africa on board a flimsy wooden boat to ferry alive lions and dragons that will be used as sport for the ruling class. Ojo did not discount the overriding importance of human rights. After all, he started his professional life as a human rights lawyer. But his insightful mind appreciated the possible limitation of a regime of right to some kind of exercise of state power. Obviously no democracy can build the Colosseum today.

Chief Ojo Maduekwe represented the most sustained attempt by any well-known modern Nigerian politician to give serious philosophical thoughts to the challenge of development in Nigeria. He once wondered whether the fact that we don’t have the exact translation of the word ‘corruption’ in most of our indigenous languages may be a contributory factor to our poor standing in anticorruption. His point was that until we can culturally domesticate the values of accountability and transparency we may continue to struggle with pervasive corruption

Ojo committed a lot of brain power to the question of corruption, democracy and development in Africa. His collection of speeches, Raising the Bar, reads like a selection of essays by an expert social anthropologist. He wrote extensively on development of civil society, religion and politics in Nigeria, constitutional reform, good governance and development, corruption and the Nigeria project. Apart from political and development issues Ojo reflected so much on art and culture, literary criticism and theology. His lecture at Harvard University on the poetry of Chris Okigbo and the politics of Nigeria is a treatise on the poetry of revolutions.

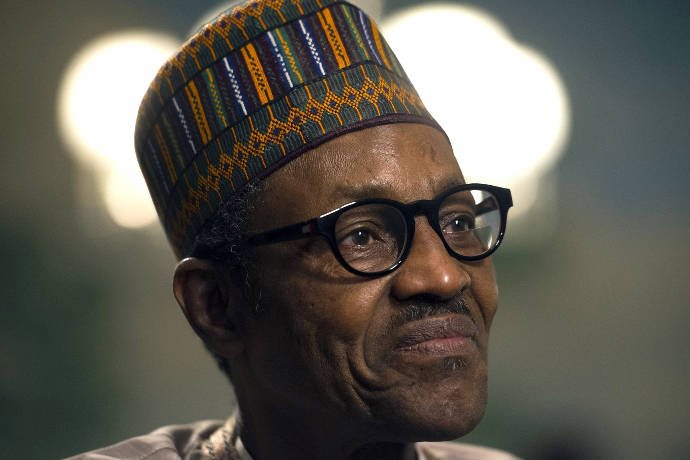

In 2004 Ojo was invited by the federal government to deliver the first Nigerian Independence Anniversary Lecture. It is a magnum opus. After presenting a social barometer of Nigeria as either a failing state or at best a weak state, Ojo concluded that Nigeria’s salvation lies on generational determination to “create an Opportunity Society”. Even as paid up member of the ruling elite Ojo did not pull back from radical ideas as long as that is where good reasoning led. As the National Secretary of the ruling PDP, he argued that the litmus test of the party’s commitment to consolidating democracy is to continue to improve the quality of competitive election until it ‘reforms’ itself out of power. It seems as though Ojo was prophesying about the 2015 electoral defeat of the PDP.

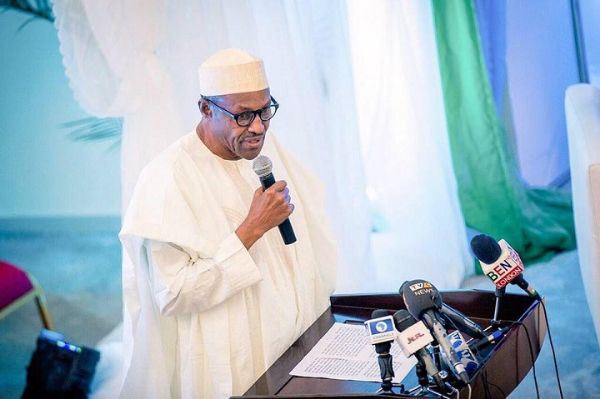

Ojo’s unique contribution to politics in Nigeria is to unify the politician and the thinker in one person. The image of the politician as a man who either lacks the faculty of deep thought or disdains ideas is one that reinforces the bawdry and moronic nature of politics. Ojo, in a phenomenal burst of energy in more than 13 years as politician and technocrat in power, has retrieved the important art of politics from the dim-witted anti-intellectual. It is now our privilege and responsibility as his colleagues, contemporaries and acolytes to deepen this bond between thinking and politicking.

Why did Ojo serve every government since 1999? It is because Ojo suffered a fatal misjudgment. This error dates back to the legendary Plato. Like Plato, Ojo had believed that the king could become a philosopher once exposed to the joy of philosophy. Like Plato, Ojo was disappointed by the King who pretended to love philosophy. Also, like Plato, he kept returning to Sicily with vain hope that the new King will somehow understand the importance of philosophy to statecraft. Just as the wily Dionysius and his son used Plato and still did not become philosophers, the Kings Ojo served did not become the wise builders he hoped they would become. He tried to turn Kings into philosophers but did not succeed.

We will miss Ojo sorely. But we are consoled that he has left us a task and a challenge that dates back to the travails of Plato in the “Lure of Syracuse’. His many successes will inspire us. And his few failures will chasten us as we continue in the quest for excellence, the end of which is to discipline politics so that it can truly become the handmaid of philosophy. Ojo: mekaria.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.

Add a comment