BY RITA OKONOBOH

“Our common enemy is COVID-19, but our enemy is also an “infodemic” of misinformation. To overcome the coronavirus, we need to urgently promote facts and science, hope and solidarity over despair and division,” reads a post by Antonio Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations (UN), on Twitter in March 2020.

Despite the concern expressed by Guterres at the start of what became a pandemic, fake news and misinformation on COVID continued to spread worldwide. In Nigeria, there was widespread misinformation coupled with homegrown myths and conspiracy theories on and outside of social media platforms. A long list of false claims followed the detection of COVID in 2019, and after Nigeria confirmed its first case in February 2020. Some claimed their vaccine injection sites caused light bulbs to turn on. Others said hot weather kills the virus. Added to these claims were links to infertility, the only-for-the-rich mantra, and rumours that some people developed magnetic skin after getting vaccinated.

While misinformation can be harmful, and even deadly, it can be difficult to stop. Anyone can spread a false claim through social media, with a few options for holding them accountable. With current global concern on the possibility of another major health crisis considering the recent reports of a sudden spike in COVID cases in China between April and May 2023, is COVID related misinformation still affecting Nigerians’ views? And, what can be done to counter it?

Advertisement

THE FACES OF MISINFORMATION IN NIGERIA

Nine months after the UN expressed concern over the “infodemic of misinformation,” Dino Melaye, former senator for Kogi west, encouraged Nigerians—and all Africans—to reject the COVID-19 vaccine. In a video, he repeated false claims and spread doubt about the vaccine’s development that ignored medical science. Checks as of June 2023 showed the video garnered over 76,000 views, and although a significant percentage of comments dismissed the senator’s claim, there were some comments that aligned with his position. The claim was fact-checked by TheCable and found to be false.

Advertisement

Fake news is not new to Nigeria or isolated to COVID-19. Despite efforts to address its harmful effects, especially in relation to the COVID pandemic, research shows it can be difficult to counter misinformation once it takes root, whether or not there is evidence disproving it. In Nigeria, fact-check reports by the media and sensitisation by health organisations including the WHO, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), and Nigeria’s federal ministry of health, among others did not overcome the proliferation of misinformation on social media and beyond.

The COVID vaccination rollout faced real challenges, including the strict storage and transportation requirements and short shelf lives of most types of the COVID vaccines, as a result of which hundreds of thousands of vials were destroyed in December 2021. Also, the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) had set a target of fully vaccinating 70 per cent of its eligible population by December 2022. However, as of January 3, 2023, the figure stood at around 63 million persons.

Although Nigeria has recorded an increase in persons who are listed as fully vaccinated (the figure climbed to around 75 million as of June 2023), there are still concerns about the number of actual vaccinations and attitudes toward COVID, especially with the media reports in 2020, 2021, 2022, and even as recently as January 2023 on fake COVID test results and in some cases, vaccination cards issued with no jabs actually received.

And this begs the question: Does old fake news on COVID still influence decision-making, even after such claims have been found to be untrue?

Advertisement

‘MELTED EGGS’, ‘SHORTENED LIFESPAN’, ‘ANTI-CHRIST LINK’

Among several persons interviewed between February and April 2023 was Ijeoma Nwankwo, a resident of Lagos, who said a claim on the effect on fertility, a common and global myth that was repeatedly debunked, resulted in her decision not to take the vaccine.

“I heard that once you take the vaccine, for women, you won’t be able to give birth and that your eggs would melt away. This claim influenced my decision not to take the vaccine because I want to give birth in future. [There were other claims which were] described as fake news, and I don’t really know if they are true because I don’t know anyone close to me who took the vaccine. For now, I don’t see myself taking the vaccine,” she said.

Hauwa Saidu, a resident of Nagbe community in Niger state, said although she was also told by fellow residents that the vaccine could affect fertility, she eventually took the vaccine after she saw that there were no serious negative effects as claimed.

Advertisement

“Honestly, I was very scared of taking the COVID-19 vaccine when we were told it was available in the country because we heard a lot of speculations. I was told it was a way of reducing a person’s lifespan, and that we will die quickly. I was also told that it makes a woman infertile which was why I didn’t take it. After a while, I decided to take it after people took it and nothing happened,” she said.

Favour Akhigbe, a resident of Edo state, said her decision not to take the vaccine was because she “heard that people taking the vaccine were dying; that people were reacting to the vaccine”.

Advertisement

“The stories about the vaccine partly influenced my decision not to take the vaccine, because initially, I doubted those stories claiming that the vaccines could kill. However, I also don’t like needles, and I am healthy – nothing is wrong with me. With the way I am feeling now, I don’t see the need to take the vaccine. However, should I be infected and it’s confirmed that it’s COVID, then, I’ll consider taking the vaccine,” she added.

Meanwhile, Favour’s position on waiting to get infected before taking the vaccine runs contrary to the lines of science and health safety. The vaccine works to reduce transmission of COVID-19, and to decrease the severity of symptoms should a person become infected with the virus. However, it has these benefits only if taken before a person becomes infected. Once someone has COVID-19, the vaccine is not a treatment for that infection, though it may protect the recipient from future infection.

Advertisement

Osagie Wisdom, who was vaccinated in Delta state, said although he had his reservations, many of the claims on COVID were from third-party sources within his community as well as social media.

“I heard testing was taking time and it was only done for rich folks. Later on, there were claims on social media that the vaccines were adulterated and, in some cases, fake, and these were the ones given to the poor masses. There was no first-hand info on all these claims though; it was more of ‘them say, them say’. Regardless of these claims, I took the vaccine in Delta state,” he said.

Advertisement

Yetunde Odeyemi, a student at the Federal Polytechnic, Ilaro, Ogun state, said although she eventually took the vaccine, she was first concerned over claims that spread via social media platforms that one would get the virus from the vaccine. This claim has also been repeatedly debunked as studies state that science does not support such a theory.

Nafo Nafo, a resident of Kuta in Shiroro LGA of Niger state, said before taking the vaccine, the things he was told made him scared.

“When the COVID-19 vaccine was introduced, I heard people saying that it is capable of making someone become impotent. I was so scared and I decided not to take the vaccine. As time went on, I saw some people who later took the vaccine and informed me nothing happened to them. I was scared but I have faith in God that I will be safe,” he said.

Another resident of Edo state, who identified himself simply as Collins, said he didn’t take the vaccine because he had reservations about the time frame within which they became available.

“I heard that it’s a thing of the anti-Christ. I also heard that vaccines were used to distribute diseases. They sounded outrageous and were eventually proven to be fake news as far as I know. However, I didn’t take the vaccine because I felt it was rushed. It may be what it is, but vaccines take years to create. The COVID-19 vaccine was produced in a year or two. For me, the decision to take the vaccine will always be influenced by how safe I think it is, and how much I think I need it,” he said.

However, to answer Collins’ concerns, the COVID-19 vaccine was developed through an unprecedented global effort that included large amounts of funding from many sources and was informed by years of vaccine research and technology. While the SARS-CoV-2 virus was new, coronaviruses are not. So, scientists had a lot of prior knowledge that helped them understand the virus and develop a vaccine quickly.

Collins added that he considers himself young and “with a strong immune system”, and as such, sees no need to take the vaccine. However, this echoes another myth about COVID-19: that young people do not need to get vaccinated. While young people are less likely to experience severe effects from COVID-19, some do still get extremely ill, have long-term symptoms, or die. And, this myth overlooks the fact that if young people are infected, they can spread the virus to others who constitute the percentage of more vulnerable people in their communities and households. When people of all ages are vaccinated, the virus spreads more slowly.

On her part, Oluwabunmi Taiwo, a resident of Ibadan, Oyo state, said the fake news on COVID influenced her decision not to take the vaccine, adding that even though they were eventually debunked, “Maybe I still believe them, or maybe not, it doesn’t really bother me anymore”.

Favour Felix, another student, said while she would focus on building her immune system to withstand infections, fake news on COVID would have no impact on her decision to get vaccinated.

“Initially, I heard that if you take the vaccine, you are going to start manifesting certain symptoms. However, my relatives in the medical field took it, and they’re normal. When I got to know about taking the vaccine, the virus was not really everywhere again, and I felt like I should just focus on boosting my immune system. As such, I saw no need to take the vaccine although all the people I knew who took the vaccine didn’t manifest any of the claims. That way, I knew the claims were fake news. Such claims won’t affect my decision in the future though,” she said.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF FAKE NEWS

There have been various studies on what makes people susceptible to believing fake news, and findings have listed several factors including political biases, social influence of the individual/platform sharing the misinformation, as well as what Adam Wyatz, a professor of psychology at the Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences identifies as “motivated reasoning” (information that aligns with a person’s biases that have formed over time) and “naïve realism” (the inclination to believe that one’s perception is the only fact).

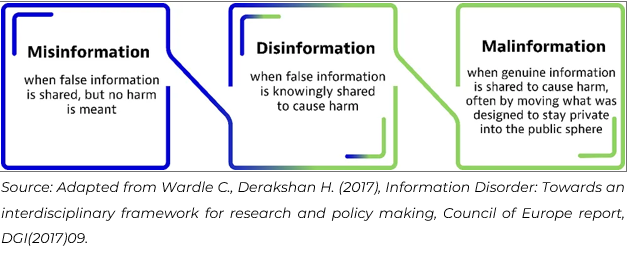

Speaking on the influence of fake news and why it has such long-term effects, Oyesoji Aremu, a professor at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, said the psychology behind the lasting impact of misinformation and disinformation is related to how pervasive it is, and how it stays in the information ecosystem even when it is disproved.

“Nigerians are quick to believe fake news because such news gains are grounded very well on social media. Unfortunately, this is not censored. It goes without saying that man, by his nature, believes too much in such news mainly because of the attention that comes with it,” Aremu said.

Temple Uwalaka of the University of Canberra in Australia, in a study involving 254 persons, found that “fake news and fake cures on social media about the COVID-19 pandemic have an adverse effect on the people as it causes people not to trust official guidelines”.

‘FAKE NEWS SHOULD ATTRACT SANCTIONS’

Aremu acknowledged that the federal government and the media made attempts to sensitise the public, which were also supported by efforts from international organisations to provide information and debunk claims not supported by expert knowledge. He, however, recommended legislation targeted specifically at holding people accountable for creating and spreading misinformation, considering the impact on the country’s health system and the effects on individual well-being.

“There should be legislation to regulate fake news. This should also attract sanctions,” he added.

‘ACTING ON THE WRONG INFORMATION CAN KILL’

Misinformation can be deadly. The WHO, in April 2021, said between January and March 2020, “nearly 6,000 people around the globe were hospitalized because of coronavirus misinformation”. Meanwhile, a study published in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, found that a claim which circulated at the time that consuming “highly-concentrated alcohol” could kill the virus led to the death of around 800 people, with more than 5,000 people hospitalised, while at least 60 persons went blind “after drinking methanol as a cure of coronavirus”.

With the growing influence of fake news, misinformation, and disinformation within and well outside social media platforms, there is a need for more deliberate efforts geared towards addressing such claims as were seen during the height of the COVID pandemic, to ensure that in the event of global health emergencies, fake news doesn’t overwhelm facts when the next crisis comes calling.

As the WHO said, “Acting on the wrong information can kill”.

This story was supported by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) as part of its Public Health Reporting Corps (PHRC) initiative.

Add a comment