On November 17, a soldier fighting insurgents in the north-east ran amok and shot dead Alem Muluseta, an aid worker with Medicine de Monde (DM). He wouldn’t stop there, he also killed a co-soldier on the spot.

According to an eyewitness, Muluseta was landing at the military helipad in Damboa, Borno state, in the company of her colleagues when she was shot.

A helicopter co-pilot was also hit by bullets, just before the soldier was killed by his colleagues.

It is not yet clear why the soldier opened fire on people he was meant to protect, but since the news broke out, discussions around mental health and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), especially among soldiers, have been brought to the fore.

Advertisement

PTSD is a mental health condition triggered by a terrifying event, with flashbacks, nightmares and severe anxiety, as well as uncontrollable thoughts about the event as possible symptoms.

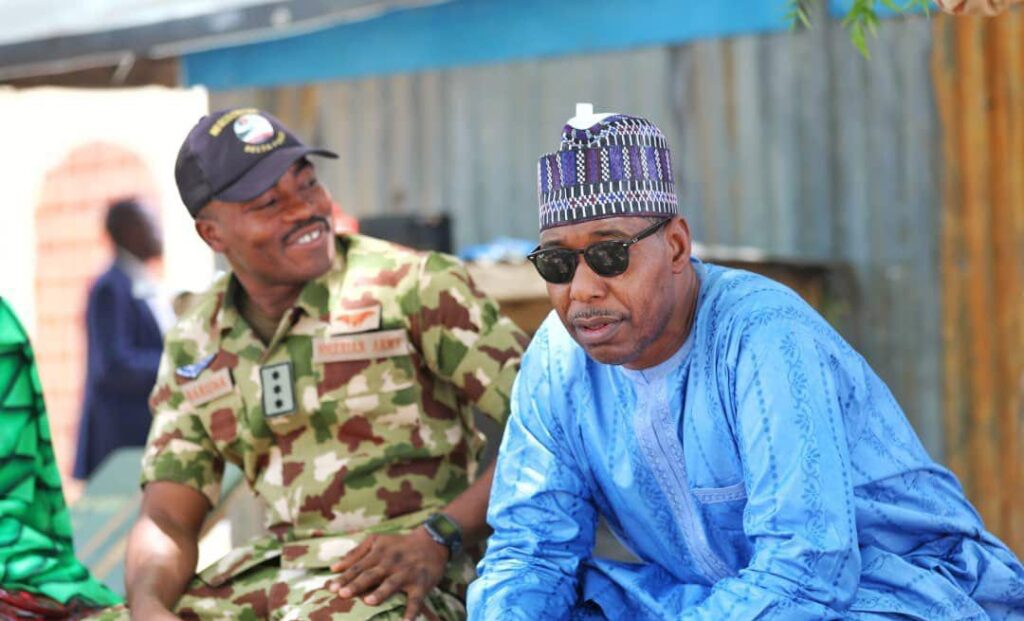

In a condolence letter to the United Nations (UN), Babagana Zulum, Borno governor, ascribed Muluseta’s killing as a “sad isolated incident”, adding that the state will continue to work together with the military, and partners to support mental health programmes in the theatre.

However, this was not the first time such an incident was recorded.

Advertisement

In July 2020, Azunna Maduabuchi, a trooper with the army’s 202 battalion in Bama, Borno, killed a lieutenant who did not give him a pass to visit his family.

A pass is written permission to be away from one’s military unit for a limited period of time.

The soldier had requested the pass to visit his family over an urgent matter, and when he was turned down, he fired shots at the lieutenant who is the battalion’s adjutant responsible for administrative matters.

Six months later, a court martial sitting at the Nigerian army 7 division in Maiduguri, Borno capital, sentenced Maduabuchi to death. Maduabuchi’s story was said to be from messed-up mental health to a death sentence.

Advertisement

According to experts, his case is a common scenario of how PTSD haunts military personnel after months on the battlefield.

A DISTURBING TREND

In another incident that took place in 2018, Adegor Okpako, a staff sergeant attached to 192 battalions in Gwoza, killed himself and two of his colleagues in a case of accidental discharge during an in-theatre training.

However, some sources claimed it was a suicide case as no training was ongoing when the incident occurred.

Advertisement

Okpako was said to have killed himself two days after returning to the battalion from a short break. No available evidence showed he was receiving treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder or any form of mental health crisis.

In 2017, T. Mani, a captain in the army’s 28 brigade headquarters in Mubi, Adamawa state, led an emergency response patrol team following a call that one Silas Ninyo, a staff sergeant, was beating civilians at a nearby location.

Advertisement

Upon arrival, Mani and his team members prevailed on Ninyo and rescued the civilians from him; but the situation quickly turned fatal when the servicemen tried to disarm their raging colleague. Ninyo opened fire and killed Mani.

In 2018, another Nigerian army captain who was on deployment in the north-east committed suicide at the 7 division hospital in Maiduguri. The captain was referred there for medical examination and treatment. He was said to have flipped his rifle toward his stomach and opened fire.

Advertisement

Before the officer killed himself, he threatened to shoot a storekeeper at the medical centre armoury. After the scare, the captain shot himself.

Aisha, wife of President Muhammadu Buhari, during the foundation laying ceremony of the PTSD Wellness Centre initiated by the Defence and Police Officers Wives Association (DEPOWA), narrated how her husband suffered from PTSD after he left the military.

Advertisement

Buhari, a former military ruler who had been to wars and had led a couple of military units, retired as a major general.

His wife said many soldiers are either wounded physically or mentally as a result of terrifying experiences during the course of duty.

“Being a soldier’s wife or a retired soldier’s wife and a wellness expert, I understand the challenges associated with PTSD and its impact on military families and the nation,” Aisha said.

FAR AWAY FROM HOME

Nigeria is in its 12th year of the war against the Boko Haram/ISWAP insurgency in the north-east. In the last three years, the security situation became complex with the reign of bandits in the north-west and north-central geopolitical zones.

The remaining three zones are not spared by the spate of insecurity as kidnapping and farmer/herders crises are on the rise. All of these have led to the expansion of military operations and the deployment of more soldiers and officers.

TheCable conducted random interviews among twelve soldiers in the 28 taskforce brigade Chibok and it was discovered that some of them have been on the war front for nearly a year. They were not given a pass to see their loved ones.

According to one of the soldiers who is in his fifth month on the battlefield, the non-issuance of passes to officers has caused them “eternal pain”, while some are losing their minds without proper care.

The trooper added that some soldiers have lost control of their families, while some have been divorced by their partners following their long stay on the field.

“There is an instruction from the chief of army staff that officers and soldiers should be given a pass after working for 3 months,” one of the soldiers who requested anonymity told TheCable.

“Some soldiers have spent eleven months here without seeing their family; some six, some seven months. Other brigades are issuing passes to their men to go see their families without any issue.

“It is now worse that our families are thinking we don’t want to show up. The thought alone is enough to demoralise us. Giving us passes to go see our families is a form of welfare this new theatre commander is denying us.

“If we should open up about what it feels like to the theatre commander, the next minute, you are sent to the guard room.

“At times, I will just be here alone thinking about my family and my life in general. I haven’t seen my family for the past five months. Last two nights, my wife called that she was coming to Chibok to see that I am alive. I had to ask her, where am I going to keep you when you come?

“We don’t even have access to medicine to take care of ourselves. We will get to our hospital here, the nurses will write drugs in a paper for us to go get it outside.”

EXPERTS CALL FOR URGENT DEPLOYMENT PLANS

In a 2006 comparative study, the prevalence of PTSD in a sample of hospitalised soldiers evacuated from the Liberian and Sierra-Leonean wars, in which Nigerians were involved as peacekeepers, was found to be 22 percent and survivor guilt was found in 38 percent.

According to the study, PTSD was significantly associated with a long duration of stay in the mission area, among other causatives.

Freedom Onuoha, a political science professor and coordinator of the security, violence and conflict (SVC) research group at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, said that many more PTSD-related fatalities may be recorded in the army when officers are kept on extended duty tour.

In the military, a tour of duty is usually a period of time spent in combat or in a hostile environment.

Onuoha said extended duty tours, the decrepit condition of soldiers, poor welfare packages, and the absence of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) contribute to the incidents of PTSD in operational theatre and even during the post-service life of soldiers.

“PTSD is an enduring feature of the life of most combat officers who have been exposed to battle or violence in extremely hostile environments. The repeated incidents call for an urgent overhaul of military’s deployment plans and troop rotation framework to ensure that officers and soldiers do not suffer extended stay in duty stations,” the professor said in a chat with TheCable.

“There is equally the need to stand up and deploy a mobile team of psychologists (MTP) vastly experienced in CBT to routinely visit theatre of military operations and campaigns to review the psychological states of our troops with a view to recommending or administering appropriate counselling sessions and therapies to those in need of help.”

Sani Usman, a former army spokesperson, said the military needs to pay attention to the prolonged stay of troops in the theatres.

“I would like to suggest that the military thoroughly investigate the circumstances that led to the heinous incidents in order to understand the motivation behind it, as it could be due to post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, or other social reasons,” Usman said.

“Therefore, there is a need to look at the prolonged stay of troops in the theatre, curb the proliferation of banned substances and stimulants and evaluate the relationship between the military and civilians, particularly the humanitarian workers, with a view to enhancing it.

“Commanders at the various levels should also be more aware of their responsibilities in terms of effective monitoring and administration of their troops.”

TheCable reached out to Onyema Nwachukwu, army spokesperson, on efforts the military has put in place to help the mental health of soldiers on the front line. But he didn’t respond to calls and messages sent to his phone.

With the spate of emotional outbursts by soldiers on the frontline, all eyes are on military authorities to set the tone for a safer psychological atmosphere for the troops securing the country from internal and external aggressors.

Add a comment