She couldn’t wrap her head around the question being asked of her. She couldn’t fathom the interest in her private business. Try as she may – even with constant nudging – she failed to come to terms with a man’s query about her period. Since she was a little girl, she has been taught to conceal that part of her life from the world, to cower in shame at the mention of it and never to speak of it with anybody, particularly men. So, rather than divulge what was being asked of her, she assumed a defensive posture; folded her arms across her chest and looked away to ward off oncoming intrusions. She was done with the conversation and no amount of prodding could pull her back.

Hauwa, resident of Rugan Fulani community in Abuja, is not alone in her reluctance to talk about her period. The myths and taboos surrounding menstruation are drilled into the psyche of girls from a young age such that they are unable to speak freely about it, even when they need help.

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) – the practice of using sanitary materials to absorb menstrual blood that can be changed privately, safely, hygienically, and as often as needed – is a sore subject.

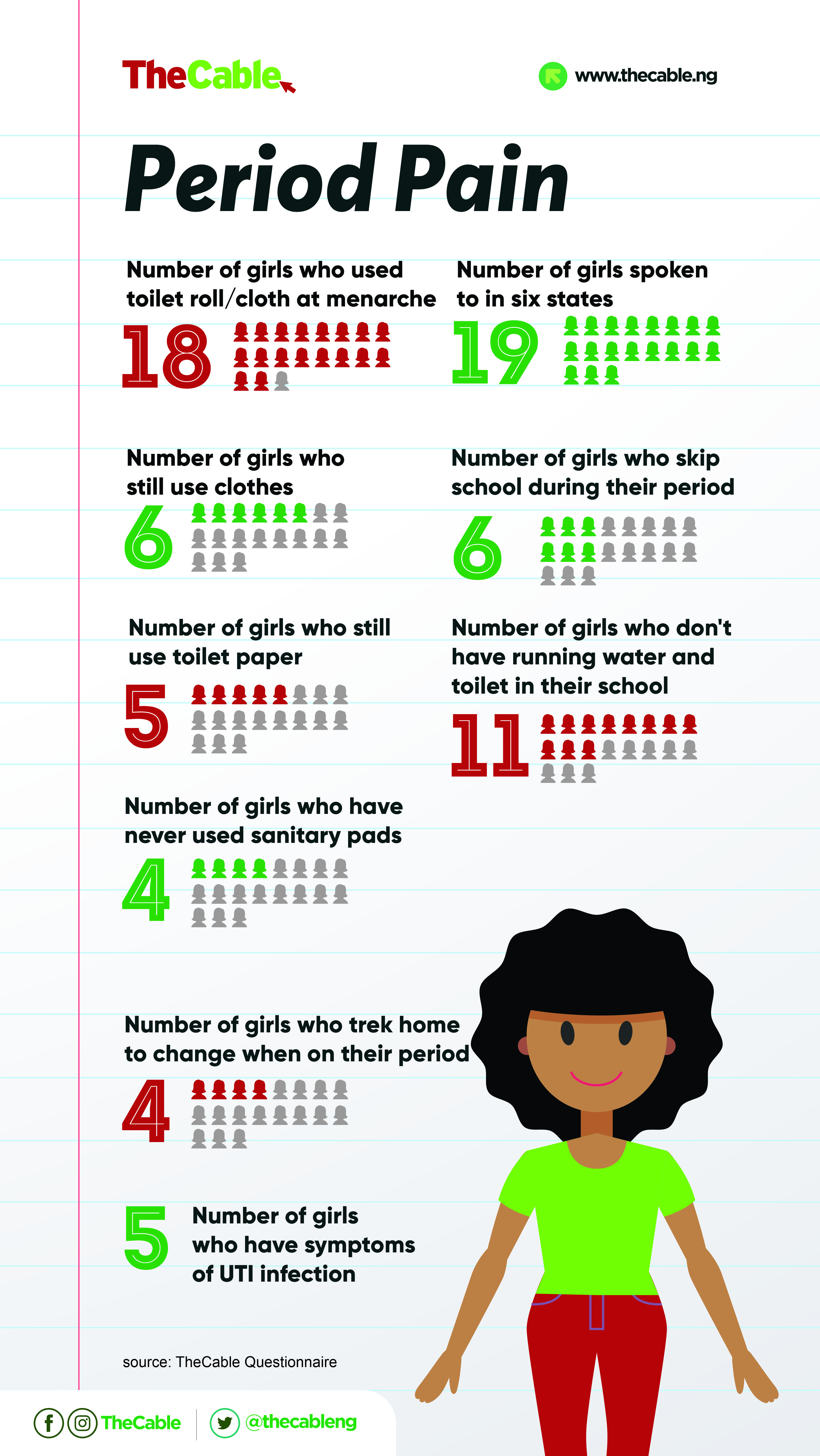

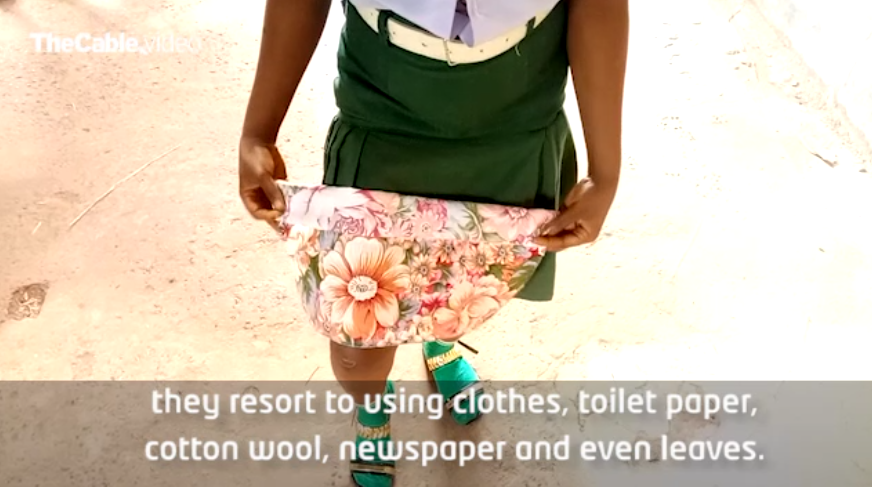

For many girls in Nigeria’s rural communities, their period comes with pains that leave scars in their wake. Largely as a result of poverty, government inaction and lack of accountability, many girls have no usable toilets and running water in their schools or homes. They cannot afford sanitary pads, and are forced to use pieces of clothes, toilet paper, leaves and cotton wool to take care of Aunt Flo.

Advertisement

This leaves them susceptible to urinary tract infections, fungal diseases, sepsis, hepatitis B and increased risk of cervical cancer.

These girls are endangered species – and there are millions of them across the country.

MEET SYLVIA, WHO SAYS ‘MY PERIOD IRRITATES ME’

Advertisement

Like many girls of her age-group, Egah Sylvia – an SS2 student of Government Senior Secondary, Mabushi, Abuja – uses a piece of cloth to pad-up her flow during her period. Although it is not a comfortable experience, Sylvia “can’t afford to buy pad all the time”.

“I often feel uncomfortable because it is too big to go into my pant so I cut it into tiny pieces – but that does not absorb the flow,” she says.

The 16-year-old lives in a nameless cluster in the heart of Mabushi. The conjoined slum is among many of its kind embedded inside towns and scattered all over Abuja.

In Sylvia’s slum which has an estimated population of 1,200, there are no toilets. Children and adults venture into an open defecation site just on the fringe of the settlement whenever nature calls. Surprisingly, the site serves multiple purposes: toilet, wasteland, and farmland during the rainy season.

“Anytime I come here, I feel like throwing up,” she says as the deep stench of human waste hangs in the air.

Advertisement

By the time she started feeling itchy sensations in her private part area, a nurse advised the teenager to avoid the open defecation site and urged her to instead pass waste inside polythene bags.

The existing bathroom behind her house is covered with maps of algae, and because there is neither running water nor borehole in the slum, she has to walk some distance to buy water, particularly when she has to clean up during her period.

Due to her inability to afford a sanitary pad, Sylvia is condemned to be on her feet while in school so as to avoid contact between her skirt and the piece of cloth used in place of sanitary pad.

“Sometimes, I don’t sit down. If I am tired of standing, I will just manage to sit at the edge of my seat,” she says, adding that when she gets blood-soaked in school, “I have to stand till school is over and then I rush home”.

Advertisement

In GSS Mabushi, there is no running water in most of the toilets and a majority of them are in poor shape. Hence, girls have to fetch water from a central tap and carry to the toilet when they need to clean up during menstruation.

But in the case of emergencies, they have to be creative. One of such emergencies once took Sylvia by surprise.

Advertisement

“I was urinating and the piece of cloth I used for my period fell on the floor. My school toilet is not clean so I had to pick it up and hide it somewhere no one will see it,” she recounts.

As she speaks, Sylvia drops her gaze, clearly hesitant to relive the unpleasant memory. After a few seconds, she adds: “I don’t like seeing my period. It irritates me.”

Advertisement

Sylvia is among the 25 percent of Nigerian women and girls who lack adequate privacy for defecation or MHM, according to the World Bank’s WASH Poverty Diagnostics Initiative.

Advertisement

Globally, women and girls face difficulties when managing their menstruation but in a low-income country like Nigeria, the situation is worse. According to UNESCO, a focus group conducted among women in Nigeria revealed that almost all adult women, young women and girls have used rags during menstruation.

DURING PERIOD, ‘IT’S BETTER TO STAY HOME THAN GO TO SCHOOL’

A few miles away from the slum Sylvia lives is another settlement, home to Esther John, an 18-year-old who attends the same school. She uses a sanitary pad when her parents can afford it and “sometimes rag” when there is no money.

Esther, from Plateau state, goes to school prepared, making sure to pack an extra piece of rag for any unexpected flow. Since there’s no water in her school’s toilet, the teenager cleans up with N10 sachet of water.

But she was not always that well-prepared to deal with the arrival of her period. Back when she was in junior class, it would often take her unawares.

“When I did not have rag, tissue or pad, I get wet sometimes in school. I will look for cardigan and wear it on top of my skirt,” she says.

At such times, Esther says she would have to take permission to leave the school premises because “it’s easy to get water at home”. And that would be the end of school for that day, and sometimes until her period is over.

“It’s better for me to stay at home than to go to school,” Esther tells TheCable.

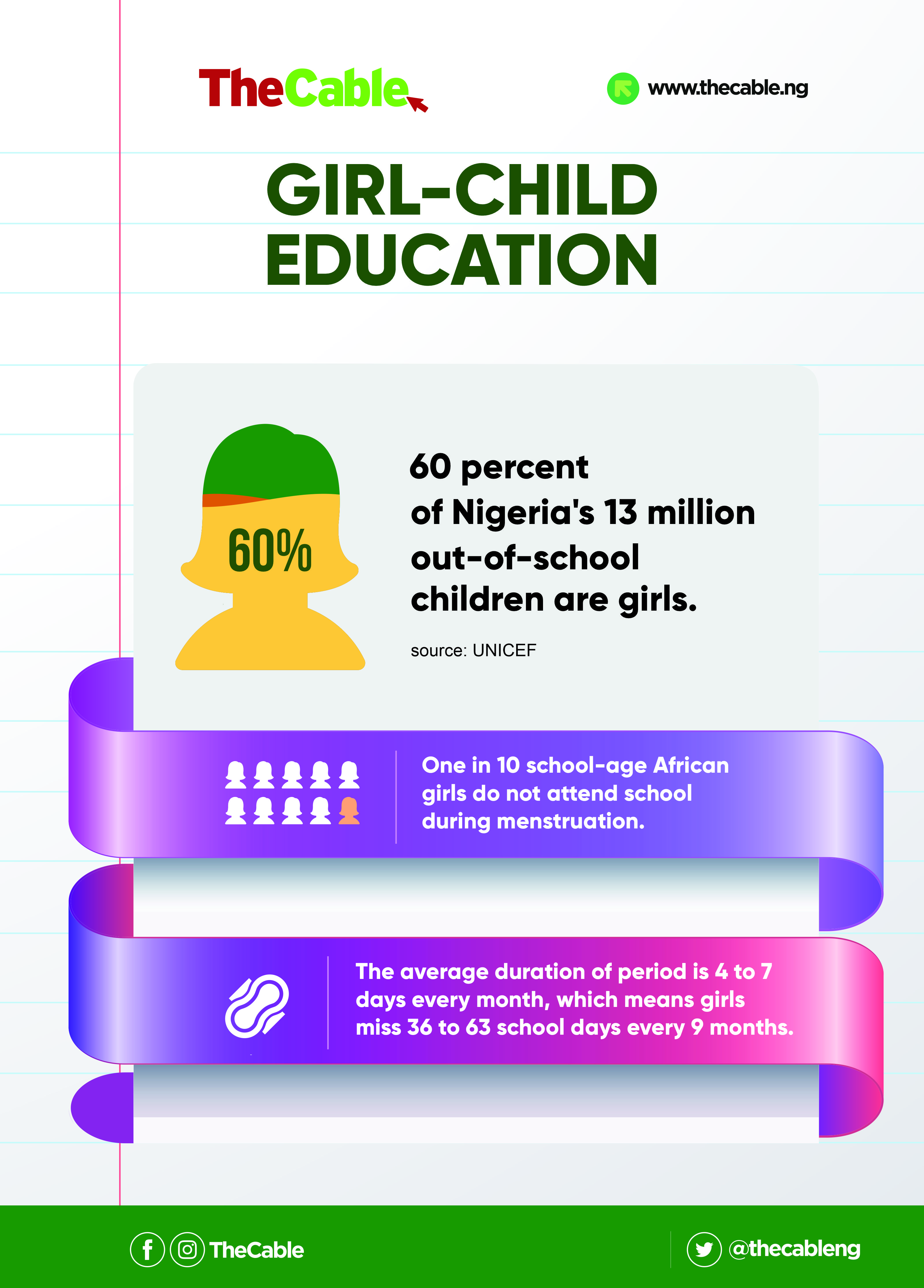

In developing third world countries, 60 percent of women and girls do not have access to sanitary products mostly due to poverty. A report by UNESCO estimated that one in 10 school-age African girls do not attend school during menstruation, which is between four to seven days every month.

Chinagorom Emmanuel, 16, had her first period at age 12 and because she also uses cloth, she rarely goes to school during her period, except towards the end when the flow reduces.

“I don’t like coming because whenever I’m in school, it stains and the blood is too much. There is no water in our school and it’s difficult to clean up when I get wet,” says the SS1 student of Omolua Secondary School (OSS), Igbanke, Edo state.

Staying away from school during their period is almost a norm for most girls of OSS, Igbanke. Ejike Chidinma, a 15-year-old classmate of Chinagorom, says period-time school abstinence is a regular practice.

Most of the girls say they are unable to afford to buy sanitary pads — even for N200 — hence they would rather stay at home.

“When I’m on my period, I don’t always come to school because when the cloth is soaked, there is no place to change. We don’t have a toilet, we don’t have water and our toilet is in the bush,” says Chidinma.

Indeed, there is neither water in the dilapidating school surrounded by thick bushes nor is there a water closet toilet in the premises. Majority of the students pass faeces and clean up in the bush while some opt for the makeshift toilet at the edge of the bush.

The toilet is made with corrugated aluminium sheet while big wooden planks form the base. Space is left in the middle of the planks for the students to pass waste.

Similarly, all the schools in the town, including Igbanke Mixed Secondary School and Igbanke Grammar School, have no functioning toilets.

During the process of easing herself in the bush, a female student was recently bitten by a snake in the town. The bite was a few inches close to her vagina area. Her screams drew the attention of her fellow students and teachers who promptly intervened and took her to the community hospital.

‘OFFENSIVE ODOUR’

In Igbanke, many girls of school age are often diagnosed with urinary tract infection and pelvic inflammatory disease at the General Hospital.

Austin Isede, a pharmacist who has treated several girls, says most times they present very late in the hospital, thereby giving the health practitioners grounds to refer.

He says out of every five girls that come into the hospital, “two or three are usually referred outside our facility for proper care. We tend to have cases of complicated vaginal discharge that have to be treated with very strong antibiotics.

“We’ve had the case of a patient who had to have her fallopian tube removed. It is really bad in rural settings.

“There was a case we recently discharged. It was hard to go near her because of the offensive odour coming out of her. In the course of our investigation, we learnt that it usually happens when she is menstruating and because it has been on for a long time, she had to be brought into the hospital. She was able to recover after some dose of antifungal and antibiotic medication.”

The pharmacist says 40 percent of the UTI cases reported at the hospital are linked to either the use of unsanitary items or unhygienic practices during menstruation.

“Out of every five cases coming to the hospital with UTI, two are linked to unhygienic ways of handling menstrual issues,” he adds.

Chinagorom Emmanuel says when she once had an infection, her doctor said it was a direct result of “the cloth that I use for my period”.

“They gave me some drugs and injections and said if I stop using the cloth, it will reduce. They asked me to stop but I have no choice. I have to use it.”

Imafidon Debbie Adesuwa, a doctor at Central Hospital Benin, also in Edo state, says abdominal pain, painful, smelly and discoloured urination are some of the symptoms of UTI.

Chinagorom and other girls of OSS tell TheCable that they often experience the symptoms listed by the doctor, indicating that some of them could be living with undetected infections.

“A girl on her period has to change her pads two to three times a day and if she has nowhere to do that, she will keep on wearing one pad over a long time,” the doctor explains.

“That moist condition facilitates the growth of micro-organisms directly into the vaginal tract. That’s an infective process going on.

“It might not necessarily start immediately. If they are using rags and they get to change it after an hour, there’s no infection coming into there because there’s no time for the growth of micro-organisms.

“But when you are using rags for hours and they get soaked, and unlike sanitary pad, there is nothing to trap the wetness. That moistness on the vagina and labia causes micro-organisms to thrive.

“Urinary tract infection, when untreated, climbs up and gets to the kidney. Pelvic inflammatory disease can start from there.”

‘I’VE NEVER USED SANITARY PAD BEFORE’

Switching between cloth/rags and sanitary pad as the pocket dictates is commonplace among girls in rural communities but that is not always the case for all of them. Some, it appears, have it worse.

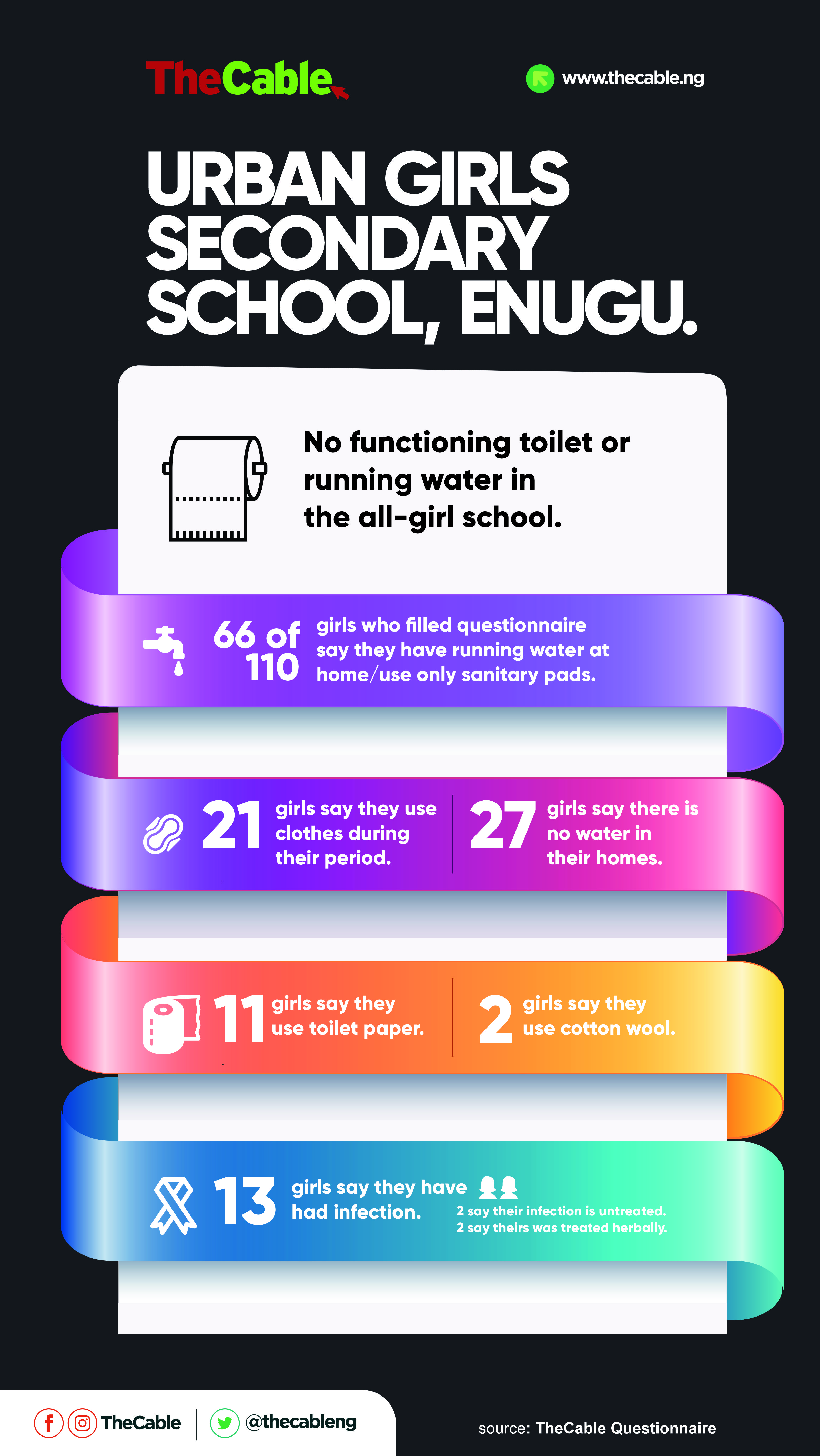

At Community Secondary School in Igbeagu, Izzi LGA of Ebonyi, 95 percent of the girls who spoke to TheCable about their menstrual hygiene management said sanitary pad is alien to them.

Happiness, 17, hit menarche at 15 and she has never used a sanitary pad. She never asks her parents for money for sanitary pad because she knows the financial situation at home.

According to the SS1 student, getting school fees from her parents is a hard enough task. “Sometimes, if I ask for money for school, I beg and cry before they give me,” says the teenager.

Happiness says when the piece of cloth she uses gets soaked, she would embark on a two-mile trek home to clean up, get fresh cloth and return to school, if possible.

“I was using tissue paper until I knew the consequence of it. Then I changed to cloth,” Happiness says while disclosing that she now completely avoids school when on her period.

“Anytime I enter into my menstruation period, I no longer come to school because it injures me. Sometimes when I use a small piece of cloth, it will fall out and I will be embarrassed,” she adds.

“So I have decided not to come to school during the five days of my menstruation.”

Although there is a pit-toilet in CSS Igbeagu, there is no running water, hence cleaning up in school is not an option.

GIRL ‘WEARS SIX SKIRTS TO SCHOOL’

When 16-year-old Faith Lucy, also a student of CSS Igbeagu, started seeing her period at age 11, her mother, she says, told her to use cloth just like she did at her age.

Ashley Lori, who runs PadUp Africa, says a girl once confided in her that her mother said she will never have children if she uses a sanitary pad, simply because she cannot afford it.

Such dangerous orientation passed down to girls from their mothers is what non-governmental organizations like PadUp Africa was conceived to change.

The NGO is into menstrual sensitization and distribution of sanitary pads to less privileged adolescent girls. To commemorate the 2019 Menstrual Hygiene Management Day, PadUp Africa distributed over 3,500 sanitary pads to girls at Command Secondary School, Bwari and FGGC, Suleja.

Asides distributing pads, Lori’s NGO also teaches women how to make reusable sanitary pads “to empower them economically by selling at an affordable price and giving to their adolescent girls”.

Lori says she decided to take on the cause when, once while driving in Abuja, she came across a group of schoolgirls with blood-stained newspapers.

She recounts: “I wouldn’t have thought someone will go as low as using newspaper for their period. When I saw the blood on the newspaper, I actually thought one of them had an injury.

“I didn’t even think one of them would be using that as an alternative to the sanitary pad. One of the girls said she wears six skirts and takes them off one after the other. And so, when the last one gets soaked, she goes home.”

FIGHTING MENSTRUAL MYTHS

As a menstrual hygiene management activist, Lori’s work with PadUP Africa has taken her to rural areas in different states in northern Nigeria.

During one of such trips, — an outreach to preach against menstrual myths in Kebbi — Lori said she came across a woman “menstruating on a hole”.

Narrating her experience, she says: “We went to Kebbi, a village called Hirishi. On getting there, a woman we spoke to was actually on her period. The hole where she sits to menstruate is by the kitchen.

“If she is to menstruate for five days, she wouldn’t go to the river because it is believed that the river will go dry and wouldn’t look up to the sun because of fears that it will cause the sun to become red.

“She won’t cook for her family and neither will she eat from the same plate as her family. They dish her food separately and toss it to her like a dog. After her period, she has to take a bath and be sanctified before she can get into the house.

“That’s one of the goriest things I’ve ever seen.”

Lori says her team was prevented from introducing sanitary pads to the community, lamenting that “we were not able to make more impact in that community”.

Inspired by her account, TheCable visited the village located in Kalgo LGA of Kebbi to speak to women there and get a sense of their period-time practice(s).

At the village, we sat with a 40-year-old woman and an elderly woman who is the midwife of the community. Both women admitted that the use of sanitary pad is non-existent in Hirishi and also noted that when girls are on their period, they stay away from the general population.

They, however, refused to speak about the practice of total isolation and seating on a hole during menstruation.

Unlike their peers in Ebonyi and Edo states, the girls of Hirishi don’t throw away pieces of wrappers used during their period. Instead, they wash and reuse until permanently stained, after which they improperly dispose in their backyard.

When asked what she uses in place of sanitary pad, 15-year-old Aisha who started menstruating at age eight said “napkin cloth”.

Speaking in Hausa, she said: “No young girl in this village has ever used sanitary pad.”

Due to a lack of education and the unwillingness of their parents to embrace ‘western culture’, most of the girls in the village have no knowledge of MHM.

Malam Momoru Umar, the village head, confirmed to TheCable that most of the girls in Hirishi do not go to school.

Education plays a huge role in proper menstrual hygiene management as girls who received pre-menarche training were found to be more likely to dispose of their used absorbents appropriately than those who had not received training, according to a 2018 study by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

SHAME & IGNORANCE ABOUT MHM

That access to education, particularly in states like Lagos, helps young girls to have a better understanding of their menstrual health.

Most of the Lagos girls who spoke to TheCable said they knew what to do the first time they had their period because they were taught about it in school.

However, in spite of that education, there still remains the twin-headed dragon of shame and ignorance about MHM.

When she saw her period for the first time three years ago, 15-year-old Ayomikun initially thought she was pregnant because her mother had said “if a man sleeps with you, that’s when you are going to see blood in your pant”.

As a virgin who had never had sexual intercourse, the resident of Makoko, a slum in Lagos state, she was both befuddled and panicky.

Recounting the traumatic experience, she said: “I was ashamed because of what my mother said. I then went to speak with one of my teachers who explained to me that I was having menstruation.”

It was for that same reason that Timilehin (14) and Folake (14) did not tell their parents the first time they had their period, opting to confide in a sister and teacher, respectively, who then advised them on how to go about it.

CEE-HOPE, an NGO that is run by Betty Abah, works to sensitize young girls in Makoko about their menstrual health, and in recent months, there have been positive results.

Opeyemi, also 14, had been using toilet paper since starting her period two years ago. The teenager says she has now “stopped using toilet roll because it always blocks the blood”.

Due to the intervention of CEE-HOPE, other Makoko girls like Opeyemi have gradually started to switch to sanitary pads, now determined to dedicate a portion of their pocket money to tackle their monthly flow in a hygienic way.

‘DECLARE STATE OF EMERGENCY’ ON MHM

Imafidon says the widespread poor state of MHM contributes to the increasing spate of poverty and further widens the gap between girls and boys, describing the situation as a “state of emergency” which “needs to be looked into urgently”.

She says Nigeria is facing a future where many young girls and women will have fungi infection, vaginal discharge, irregular menstruation, infertility issues, among others.

“If our young girls are coming down with these ailments, in future there will be a problem,” she said, adding that “they will start having issues with childbearing. Everyone has to put hands together to stop the trend so it does not escalate”.

Apart from the toll on their health, Imafidon says girls who miss school as a result of their period will be affected emotionally, psychologically, and socially.

She said: “We need the government’s attention right now; in the provision of water and clean toilets in school, provision of sanitary pads to the girls and orientation of the girls and their parents.

“The sad thing about sharing free pads is that we are not going to be there to sustain it. That’s why we are calling on everybody to help people that cannot afford sanitary pad. We need everybody to fight for the girl-child.”

According to the doctor, the problem has many ripple effects as some of the girls end up getting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) by going into relationships with men who can give them money to buy pads.

Meanwhile, pharmacist Isede opines that extensive orientation in rural areas is the key intervention needed to curb unsanitary practices during menstruation.

The pharmacist says many people living in rural areas don’t have access to information.

“For example, where I work, you will see a menstruating girl using leaves, rags and they will tell you it is what their mothers used. Some will even say it is part of their culture,” he said.

“If this thing is not checked on time, in another two, three years, we’ll start having fertility issues arising from conditions of these nature.

“Information is a major factor causing this because if they are informed, some of them can still make do with the cheap sanitary pads. Getting the right sanitary items will only come when you are informed of the right thing to do.

“Information can change their orientation over time. You will need to go back over and over again before you can change their mindset and attitude towards MHM.”

WAY FORWARD

In the face of potential health issues and declining school attendance in rural areas, many female rights advocates continue to charge the government to create an enabling environment for MHM.

But how can this be achieved?

In 2018, a few months before the general election, a coalition of #EndThe9jaTaxOnPads advocates including Olufunmilayo Harvey, a medical doctor, petitioned the Nigerian senate to take steps towards reducing the cost of menstrual products.

A letter to this effect, titled ‘An appeal to end all the taxes on menstrual hygiene products and pass The Menstrual Hygiene Bill’, was transmitted to several members of the eighth senate.

They include ex-senate president Bukola Saraki, ex-deputy sente president Ike Ekweremadu, Monsurat Sunmonu (Oyo Central) Abiodun Olujimi (Ekiti South), Lanre Tejuosho (Ogun Central), Binta Garba (Adamawa North), Stella Oduah (Anambra North), Rose Oko (Cross River North), Fatimat Raji-Rasaki (Ekiti Central), and Oluremi Tinubu (Lagos Central).

According to Harvey, the petition “got lost in the elections brouhaha and wasn’t looked into”. He added: “Since the last senate went, nothing seemed to have been done.”

Among other things, the petition urged the national assembly to craft a legislation that will mandate the federal government to subsidize sanitary pads. The petition also called on the government to take a cue from countries such as South Africa, Canada, Australia, India and Malaysia by removing the 5 percent value-added tax and 20 percent import duties on sanitary products.

Furthermore, the activists asked the government to “engage the stakeholders in the sanitary pads industries and grant them business-friendly incentives including pioneer industry status to all local companies making pads”.

They also urged the government to “give extra concessions” to companies producing reusable pads and menstrual cups; which can be used for a minimum of one year, as opposed to disposable sanitary pads.

According to the flagbearers of #EndThe9jaTaxOnPads, if these steps are taken, the prices of sanitary products will decrease.

But while relatively-priced sanitary pads are important, health experts and educationists say water availability, sanitation and good hygiene (WASH) in rural schools are equally pertinent.

State governments, they say, should make it compulsory for there to be functional water closet toilets and running water in all public schools so as to encourage girls to remain in school during their period.

This suggestion is backed by the World Bank’s 2017 Poverty Diagnostic report which advised Nigeria to invest about 1.7 percent of its GDP to achieve the SDGs in WASH by 2030 – in order “to stem the crisis in the sector”.

Isede, on the other hand, goes one step further by advocating for the mass production of reusable menstrual products so that underprivileged girls in rural areas who cannot afford disposable sanitary pads can have healthy and affordable alternatives.

Another intervention advocated by health experts and activists is the establishment of MHM clubs in public schools, where girls will be taught about the right way to go about their period and how to make reusable menstrual pads.

This approach yielded positive results when recently employed by UNICEF in Government Day Secondary School Dayi Malumfashi, Katsina state. Apart from increasing social and economic opportunities, it also reduced absenteeism.

Given the consensus of concerned parties and realities on ground, it is clear that if the nation’s leaders are serious about stemming the rising spate of poverty, menstrual hygiene management is one of the contributing factors that needs to be addressed without delay, else many poor girls will continue to remain at the mercy of their monthly blood flow – and further plunge into multi-dimensional poverty as a result of the ripple effects of their actions and inaction during menstruation.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not the views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment